Appendix VII. a Brief History of Presidential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How a Failed Assassination Attempt on Franklin Delano Roosevelt Ended in the Death of Anton Cermak, Mayor of Chicago

Review Article Clinics in Surgery Published: 07 Jan, 2019 How A Failed Assassination Attempt on Franklin Delano Roosevelt Ended in the Death of Anton Cermak, Mayor of Chicago Theodore N Pappas* Department of Surgery, Duke University, Durham NC, North Carolina, USA Abstract On February 15 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was returning from a Florida fishing trip and passed through the Biscayne Park area of Miami to give a brief speech. The mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, was in Florida on vacation and planned to meet the president-elect just after the speech. Moments after Cermak and Roosevelt shook hands, several shots were fired. A 32-year-old bricklayer, Giuseppe Zangara, was attempting to assassinate Roosevelt but missed and hit Cermak and four other bystanders. Cermak was taken to Jackson Memorial Hospital where he died 19 days later. This manuscript reviews the health care provided to the mayor during those 19 days. Although the cause of death has been contested, Anton Cermak probably recovered from his gunshot wounds but died of complicated ulcerative colitis. Introduction On February 15 1933, president-elect, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), was returning from a fishing trip off Miami. He and his security detail were passing through the Biscayne Park area of Miami for an announced stop where he was to give a brief speech. At the same time the Mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, was on vacation in Florida and wanted to meet with the president-elect. He contacted Roosevelt’s team and was instructed to wait at the grandstand area of the Bay front Park where the president-elect would be able to meet with the mayor. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6gn7b51j Author Myers, Eric Dennis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Eric Dennis Myers 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 by Eric Dennis Myers Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Joan Waugh, Chair The dissertation is a historical biography of Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940), a decorated soldier and critic of war profiteering during the 1930s. A two-time Congressional Medal of Honor winner and son of a powerful congressman, Butler was one of the most prominent military figures of his era. He witnessed firsthand the American expansionism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, participating in all of the major conflicts and most of the minor ones. Following his retirement in 1931, Butler became an outspoken critic of American intervention, arguing in speeches and writings against war profiteering and the injustices of expansionism. His critiques represented a wide swath of public opinion at the time – the majority of Americans supported anti-interventionist policies through 1939. Yet unlike other members of the movement, Butler based his theories not on abstract principles, but on experiences culled from decades of soldiering: the terrors and wasted resources of the battlefield, ! ""! ! the use of the American military to bolster corrupt foreign governments, and the influence of powerful, domestic moneyed interests. -

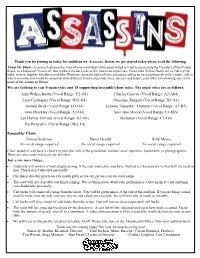

We Are Looking to Cast 9 Main Roles and 15 Supporting/Ensemble/Choir Roles

Thank you for joining us today for auditions for Assassins. Before we get started today please read the following: About the Show: Assassins lays bare the lives of nine individuals who assassinated or tried to assassinate the President of the United States, in a historical "revusical" that explores the dark side of the American experience. From John Wilkes Booth to Lee Harvey Os- wald, writers, Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman, bend the rules of time and space, taking us on a nightmarish roller coaster ride in which assassins and would-be assassins from different historical periods meet, interact and inspire each other to harrowing acts in the name of the American Dream. We are looking to cast 9 main roles and 15 supporting/ensemble/choir roles. The main roles are as follows: John Wilkes Booth (Vocal Range: F2-G4) Charles Guiteau (Vocal Range: A2-Ab4) Leon Czologosz (Vocal Range: G#2-G4) Giuseppe Zangara (Vocal Range: B2-A4) Samuel Byck (Vocal Range: D3-G4) Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme (Vocal Range: A3-B5) John Hinckley (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Sara Jane Moore (Vocal Range: F3-Eb5) Lee Harvey Oswald (Vocal Range: A2-G4) Balladeer (Vocal Range: C3-G4) The Proprietor (Vocal Range: Gb2-F4) Ensemble/ Choir: Emma Goldman David Herold Billy Moore No vocal range required No vocal range required No vocal range required Choir members will have a chance to play the roles of the presidents, tourists, news reporters, bystanders, or photographers. There are also some solo parts for the choir. Just a few more things… Auditions will consist of your prepared song. -

Copy of Italdiaspora Studies Bib 06 05 2020

Author Title Publisher ISBN Year Subject Abbot, Edith Immigration: Select Documents and Case Records Ayer Co Publsihers, North Stratford 978-0405005015 1969 History Abbot, Edith The Delinquent Child and the Home Forgotten Books 978-0282917722 2017 Sociology Abbot, Edith The Tenements of Chicago 1908 - 1935 University of Chicago Press, Chicago n/a 1936 Sociology Abbot, Edith Women in Industry Bibliographical Center for Research 978-1117869964 2010 Sociology Accolla, Paolini; d'Aquino, Niccolo Italici: An Encounter With Piero Bassetti Bordighera Press, New York 978-1599540016 2008 Philosophy Airos, Letizia, Ottorino Cappelli Guido Italian/American Youth and Identity Politics Bordighera Press, New York 978-1599540269 2011 Sociology Alaya, Flavia Under the Rose: A Confession The Feminist Press, New York 978-1558612709 2001 Memoir Alba, Richard D Blurring the Color Line: The New Chance for a More Integrated America Harvard University Press, Cambridge 978-0674064706 2012 Sociology, Race Alba, Richard D Ethnic Identity: The Transformation of White America Yale University Press, New Haven 978-0300052213 1990 Sociology, Race Alba, Richard D Italian Americans: Into the Twilight of Ethnicity Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River 978-0135066768 1985 Sociology, Race Alba, Richard D, DeWind, Josh, Raboteau, Albert J Immigration and Religion in America: Comparative and Historical Perspectives New York University Press, New York 978-0814705056 2008 Sociology, Religion Alba, Richard D; Foner, Nancy Strangers No More: Immigration and The Challenges of Integration -

Portraying the Role of Giuseppe Zangara in Sondheim's Assassins Casey Paradies

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2012 Portraying The Role Of Giuseppe Zangara In Sondheim's Assassins Casey Paradies Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Paradies, Casey, "Portraying The Role Of Giuseppe Zangara In Sondheim's Assassins" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 1265. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1265 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PORTRAYING THE ROLE OF GIUSEPPE ZANGARA IN SONDHEIM’S ASSASSINS by Casey B. Paradies Bachelor of Arts, University of North Dakota, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota May 2012 This thesis, submitted by Casey Paradies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done and is hereby approved. ____________________________________ Chairperson: Emily Cherry MFA ____________________________________ Kathleen McLennan PHD ____________________________________ Ali Angelone MFA This thesis meets the -

The Assassination of Anton Cermak, Mayor of Chicago: a Review of His Postinjury Medical Care

Published online: 2020-06-16 THIEME Original Article e105 The Assassination of Anton Cermak, Mayor of Chicago: A Review of His Postinjury Medical Care Theodore N. Pappas, MD1 1 Department of Surgery, Duke University School of Medicine, Address for correspondence Theodore N. Pappas, MD, Department of Durham, North Carolina Surgery, Duke University School of Medicine, Box 3479 Duke Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710 (e-mail: [email protected]). Surg J 2020;6:e105–e111. Abstract Anton Cermak was the mayor of Chicago in the 1930s. He was injured by an assassin’s bullet intended for the president-elect, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Cermak was taken to a local hospital, treated nonoperatively for his injuries, and initially improved. Cermak’s condition deteriorated on the sixth day postinjury, with symptoms that his doctors Keywords described as colitis. He died of sepsis on the 19th day after the shooting, and his ► Cermak autopsy revealed a perforated colon causing peritonitis. This study will review Cermak’s ► assassination clinical course and autopsy findings to determine if he died of his gunshot wound or if ► colitis he died of complications of toxic colitis. On February 15, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in Miami Representatives. He defeated a Republican incumbent and returning from a fishing trip in the Bahamas. As he passed became the mayor of Chicago in 19313 (►Fig. 2). through Miami, Roosevelt planned to give a short speech and meet, informally, with Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak. Cermak’s History of Intestinal Disease Roosevelt stopped at the Biscayne Bay Park after 9 pm and gave his 1-minute speech while sitting in his car. -

Assassins Study Guide

Civil War Study Guide.qxd 9/13/01 10:31 AM Page 3 MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL is one of the world’s major dramatic licensing agencies, specializing in Broadway, Off-Broadway and West End musicals. Since its founding in 1952, MTI has been responsible for supplying scripts and musical materials to theatres worldwide and for protecting the rights and legacy of the authors whom it represents. It has been a driving force in cultivating new work and in extending the production life of some of the classics: Guys and Dolls, West Side Story, Fiddler On The Roof, Les Misérables, Annie, Of Thee I Sing, Ain’t Misbehavin’, Damn Yankees, The Music Man, Evita, and the complete musical theatre works of composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim, among others. Apart from the major Broadway and Off- Broadway shows, MTI is proud to represent youth shows, revues and musicals which began life in regional theatres and have since become worthy additions to the musical theatre canon. MTI shows have been performed by 30,000 amateur and professional theatrical organizations throughout the U.S. and Canada, and in over 60 countries around the world. Whether it’s at a high school in Kansas, by an all-female troupe in Japan or the first production of West Side Story ever staged in Estonia, productions of MTI musicals involve over 10 million people each year. Although we value all our clients, the twelve thousand high schools who perform our shows are of particular importance, for it is at these schools that music and drama educators work to keep theatre alive in their community. -

ASSASSINS a Revue in One Act

ASSASSINS a revue in one act. Book by John Weidman, from an idea by Charles Gilbert Junior. Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. Produced at Playwrights Horizons, New York, 27 January, 1991 (25 perfs) with Jace Alexander (Oswald), Victor Garber (Booth), Annie Golden ("Squeaky" Fromme) and Lee Wilkof (Byck). Produced at the Donmar Warehouse, London, 29 October 1992 with Gareth Snook, David Firth, Cathryn Bradshaw and Ciaran Hinds. Playwrights Horizons - Off-Broadway 27 January, 1991 - (25 perfs) STORY The evening begins with "Hail To The Chief" - not in its familiar stirringly patriotic certainty, but eerily arranged for a carnival calliope, and not to announce the entrance of the President but of his would-be assassins. We are at a fairground, in front of a shooting gallery which boasts a unique entertainment: "Shoot the President - win a Prize". As the Proprietor ballyhoos his sideshow, eight figures come forward one by one to chance their luck, assassins drawn from over a century of American history. They are a disparate group, one dressed in a 19th century frock coat, another as a department store Santa. But each is handed his own distinctive gun - the preferred means of ultimate political protest in the United States. "EVERYBODY'S GOT THE RIGHT to be happy", the Proprietor asserts. Everybody's got the right to their dreams: isn't that the American way? The last to arrive is John Wilkes Booth, who promptly uses his newly-acquired weapon on President Lincoln. As the fatal shots ring out, the Balladeer steps out to sing THE BALLAD OF BOOTH - "a handsome devil who decided to take his bad reviews out on his Chief of State. -

Assassins an Application to Direct by Anastasia Foley and Zoe Jasper Part Two: the Play

Assassins An Application to Direct by Anastasia Foley and Zoe Jasper Part Two: The Play 1. Provide a brief summary/synopsis of the play you are proposing. Assassins is a musical written in 1990 with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by John Weidman. The play examines the men and women who have assassinated or attempted to assassinate U.S. presidents. Since all of the assassins come from different time periods, the show is set in a limbo like carnival in which all of the assassins, alive or dead, interact and exist. The show begins with the Proprietor of the carnival distributing guns and ammunition to Leon Czolgosz, Sara Jane Moore, Samuel Byck, John Wilkes Booth, Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, John Hinckley, Giuseppe Zangara, and Charles Guiteau (“Everybody’s Got the Right”). At the end of the scene, the audience hears “Hail to the Chief” and an offstage gunshot as John Wilkes Booth exits. The scene shifts to the Balladeer singing Booth’s story (“The Ballad of Booth”). Trapped in a barn, a wounded Booth is forcing his accomplice David Herold to document his motivations for assassinating Abraham Lincoln as threats are heard offstage from outside. As Booth dictates to Herold, the Balladeer counters that his motivations were more personal. Herold finally surrenders to the attackers outside and Booth is forced to throw the diary to the Balladeer in hopes that she will tell his story. Booth expresses that this will not be enough the fix the country and commits suicide as the barn is burned to the ground. -

Free Trade and the New Deal: the Nitu Ed States and the International Economy of the 1930S Scott Ichm Ael Nystrom Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2010 Free trade and the New Deal: The nitU ed States and the international economy of the 1930s Scott ichM ael Nystrom Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Nystrom, Scott ichM ael, "Free trade and the New Deal: The nitU ed States and the international economy of the 1930s" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11887. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11887 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free trade and the New Deal: The United States and the international economy of the 1930s By Scott Michael Nystrom A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Charles Dobbs, Major Professor Brian Behnken Linda Shenk Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2010 Copyright © Scott Michael Nystrom, 2010. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Figure 1.1 – The NRA and the Philadelphia Eagles 9 CHAPTER 2: HISTORIOGRAPHY ESSAY 16 CHAPTER 3: THE SMOOT-HAWLEY TARIFF 36 The Background -

Death in America Under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 13 | Issue 4 Article 1 Spring 2018 Death in America under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment Rob Warden Center on Wrongful Convictions, Bluhm Legal Clinic, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law Daniel Lennard Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP Recommended Citation Rob Warden and Daniel Lennard, Death in America under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment, 13 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 194 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol13/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law ` Vol. 13, Issue 4 (2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy Death in America under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment Rob Warden* and Daniel Lennard† The authors thank John Seasly and Sam Hart, Injustice Watch reporting fellows, for compiling data presented in the five appendices accompanying the article. INTRODUCTION What follows is a compilation of milestones in the American experience with capital punishment, beginning with the first documented execution in the New World under color of English law more than 400 years ago at Jamestown.1 The man who was executed, George Kendall, became first only because he had been (in the modern vernacular) “ratted out” by the man who otherwise would have been first.2 Maybe Kendall was guilty. -

2013· 2014 Season

2013· 2014 SEASON C T3 PEOPLE a ON OTHER STAGES BOARD OF DIRECTORS AT&T PERFORMING ARTS CENTER CHAIR Elizabeth Rivera SEPT 17 - 29 Peter and the Starcatcher LIAISON, CITY OF DALLAS CULTURAL COMMISSION CIRCLE THEATRE Lark Montgomery OCT 17 · NOV 16 Too Many Cooks BOARD MEMBERS Jac Alder, Marion L. Brockette, Jr., Suzanne Burkhead, Katherine C. Eberhardt, Laura EISEMANN CENTER FOR THE V. Estrada, Sally Hansen, David G. Luther, Victoria PERFORMING ARTS McGrath, David M. May, Margie J. Reese, Dana W. OCT 17 - 20 Blame It on Valentine Rigg, Eileen Rosenblum, Ph.D., Scott Williams DALLAS CHILDREN'S THEATER HONORARY BOARD MEMBERS Virginia Dykes, Gary THD W. Grubbs, John & Bonnie Strauss SEPT 20- OCT 27 Dr. Seuss' The Cat in the Hat OCT 18 - 27 Ghouls &lGraveyards NORMA YOUNG ARENA STAGE 201 -201 ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE PRODUCER-DIRECTOR Jac Alder DALLAS THEATER CENTER COMPANY MANAGER Terry Dobson SEPT 13 · OCT 27 A Raisin in the Sun SO HELP ME GOD! DIRECTOR OF BUSINESS AFFAIRS Joan Sleight OCT 4 · 27 Clybourne Park Aug. 8 - Sept. 1 DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS G(COMMUNICATIONS NOV 21 · DEC 24 A Christmas Carol a comedy by Maurine Dallas Watkins Kimberly Richard DALLAS SUMMER MUSICALS IT MANAGER Nick Rushing ocT 2 · 20 The Lion King EXECUTIVE ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT ASSASSINS Adele Acrey JUBILEE THEATRE OCT 11 - NOV 10 Neat Sept. 26 - Oct. 27 HOUSEKEEPING Kevin Spurrier a musical by Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman PRODUCTION POCKET SANDWICH THEATRE AUG SEPT Art ofMurder TECHNICAL DI RECTOR Dane Tuttle 23 · 28 OCT NOV The Werewolfof London ASSISTANT TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Dave McKee 4 - 16 OTHER DESERT CITIES MUSICAL DIRECTOR Terry Dobson SHAKESPEARE DALLAS Nov.