Induced Aggressive Mood And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

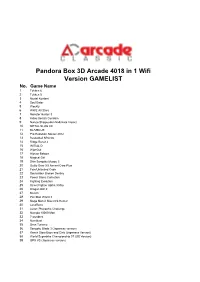

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

Kit Installation Manual

Kit Installation Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 SPECIFICATIONS ...................................................................................................... 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 2 2.1 Game Conversion Overview.. ........................................................................... 2 armgs _ ...................................................................................... 2 3.0 INSTALLATION .......................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Precautions ...................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Cabinet Preparation ......................................................................................... 4 3.3 Game Installation.. ........................................................................................... 4 4.0 SET-UP AND TEST .................................................................................................... 6 4.1 Test Mode........................................................................................................ 6 4.2 Test Mode Procedure.. .................... ................................................................. 6 4.3 TEST Menu.. .................................................................................................... 6 . 4.3.1 DISPLAY TEST.. .................................................................................. -

PC Board Price List on 17 April 2007 (Price at Exwork Hong Kong) 卓任

Address : 11/F., On Lee Building, 545 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon, Hong 卓任貿易有限公司 Kong Tel : (852) 2388-3666 Fax : (852) 2388-0860 EXCELLENT COM LIMITED EMAIL : [email protected] Website : www.excellentcom.net PC Board Price List on 17 April 2007 (Price at Exwork Hong Kong) "Super" CD Converting Mother Board + PS2 Hard Disk Console + Games = USD360 "Super" CD Converting Mother Board + X-Box Hard Disk Console + Games = USD360 New -- Arcana Heart (2D Fighting Game) 31K output Only USD860 Manufacturer System Type USD Condition 48 in 1 - Vertical Classic Game ver.308 latest PCB Various 145 New 48 in 1 - Vertical Classic Game ver.308 latest China PCB Various 134 New Multi-Game - PCB w/o power supply (PS) Manufacturer System Type USD Condition 450 in 1 (Vertical Shooting) - Multi Credit Setting (Card System More Stable) PC Various 190 New 170 in 1 (Horizontal) - Multi Credit Setting (Card System More Stable) PC Various 203 New 103 in 1 (Horizontal) - (Card System More Stable) PC Various 180 New 1000 in 1 (Horizontal) - Multi Credit Setting PC Various 180 New CAVE Manufacturer System Type USD Condition MUSHIHIMESAMA FUTARI ver.1.5 - Brand New with box CAVE PCB V Shooting 1100 New Box Kit Ibara Pink Sweets CAVE PCB V Shooting Call Used Ibara Black Label CAVE PCB V Shooting Call Used Ibara CAVE PCB V ShootingCall Used Espgaluda II - Brand New with box CAVE PCB V Shooting 600 New Box Kit Espgaluda - Used PCB Only - Japanese only CAVE PCB V Shooting 266 Used Guwange - Japanese CAVE PCB V Shooting 360 Used Mushihime Sama - Used PCB Only - Japanese -

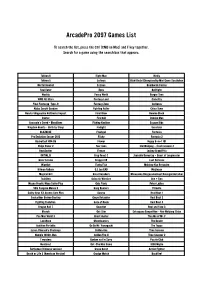

Arcadepro 2097 Games List

ArcadePro 2097 Games List To search the list, press the Ctrl (CMD on Mac) and F key together. Search for a game using the search box that appears. Tekken 6 Eight Man Birdiy Tekken 5 Enforce Bishi Bashi Championship Mini Game Senshuken Mortal Kombat Exzisus Boardwalk Casino Soul Eater Eyes Bullfight Weekly Fancy World Burger Time WWE All Stars Fantasy Land Cameltry Final Fantasy:Type-0 Fantasy Zone Cerberus Kidou Senshi Gundam Fighting Roller China Town Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact Final Blow Domino Block Daxter Fire Ball Domino Man Assassin's Creed - Bloodlines Fishing Koshien Escape Kids Kingdom Hearts - Birth by Sleep FixEight Excelsior BLAZBLUE Flashgal Fantasia Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 Flicky Fantasia 2 Basketball NBA 06 Flower Happy 6-in-1 101 Ridge Racer 2 Four lines Idol Mahjong - final romance 2 HeatSeeker Freeze Jockey Grand Prix INITIAL D Frog Feast C Jyanshin Densetsu - Quest of Jongmaster Gran Turismo Frogger ER Last Fortress WipeOut Funky Fish Mahjong Kyo Retsuden Hitman Reborn G.I. Joe EAB Meijinsen Magical Girl Gaia Crusaders Minasanno Okagesamadesu! Daisugorokutaikai Toukiden Galactic Warriors One + Two Musou Orochi: Maou Sairin Plus Gals Panic Poker Ladies Shin Sangoku Musou 5 Gang Busters Primella Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus Ganryu Real Bout 1 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny Garyo Retsuden Real Bout 2 Fighting Evolution Gate of Doom Real Bout 3 Dragon Ball Z Gauntlet Real and Fake 3 Bleach Get Star Sotsugyou Bangai Hen - Nee Mahjong Shiyo Pac Man World 3 Ghost Hunter The Adv of Mr. F LocoRoco Ghostbusters The Dealer -

Tekken Jump 1.3. by Fancyfiredrake Welcome to the King of Iron Fist

Tekken Jump 1.3. By FancyFireDrake Welcome to the King of Iron Fist Tournament Jumper! The World of Tekken is one where Devils roam among Mortals, corporations fund Tournaments and chances are you have the most messed up Family this side of fiction. The major plot of this World surrounds the Mishima family and the eternal power struggle between its members. All gunning for either Power or revenge. This conflict has spiralled out of control with the inclusion of Devils and World spanning Wars. Countless of lives have been involved in this never- ending Fight, from your average human with martial art skills to things like enhanced animals, aliens and robots. You have 10 years in this World. Fight well, avoid Volcanoes and perhaps you can become the new King of Iron Fist. Here are your 1000 CP. Use them well. Timeline First, we need to clarify at what point in the timeline you wish to start. There are so far 7 major King of Iron Fist tournaments which we will use to create an understanding of what time you will start your 10 years in. Tekken 1: The first King of Iron Fist Tournament. Kazuya Mishima, son of Heihachi Mishima, has entered to get revenge on the Father that tried to kill him. A dark power has risen inside the youngest Mishima and the Battle between him and Heihachi will give birth to the most destructive legacy in this World. Tekken 2: Heihachi Mishima survived… and he is back for revenge. Two years after the events of Tekken, Father and son will clash once more but the Power inside of Kazuya has started to consume him. -

1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 WWE All Stars 5 INITIAL

GAMELIST / LISTADO DE JUEGOS 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 WWE All Stars 5 INITIAL D 6 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 7 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 8 Dragon Ball Z 9 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 10 LocoRoco 11 Turtledove (Chinese version) 12 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 13 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 14 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 15 Street Fighter Alpha 3 16 Street Fighter EX 17 Bloody Roar 2 18 Tekken 3 19 Tekken 2 20 Tekken 21 Golden Eye 007 22 1080 Snowboarding 23 Aero Gauge 24 Air Boarder 64 25 Akumajou Dracula Mokushiroku - Real Action Adventure 26 All Star Tennis '99 27 Army Men - Sarge's Heroes 28 Automobili Lamborghini 29 Batman Beyond - Return of the Joker 30 Beetle Adventure Racing! 31 Big Mountain 2000 32 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. 33 Blues Brothers 2000 34 Bomberman Hero 35 Buck Bumble 36 A Bug's Life 37 Bust A Move '99 38 Carmageddon 64 39 Centre Court Tennis 40 Chameleon Twist 41 Chameleon Twist 2 42 Choro Q 64 43 City Tour Grandprix - Zennihon GT Senshuken 44 Clay Fighter - Sculptor's Cut 45 Cruis'n World 46 Cyber Tiger 47 Destruction Derby 64 48 Dezaemon 3D 49 Doraemon 2 - Nobita to Hikari no Shinden 50 Dual Heroes 51 Extreme-G 52 Extreme-G XG2 53 F-ZERO X 54 Flying Dragon 55 Ganbare Goemon - Derodero Douchuu Obake Tenkomori 56 Gex 3 - Deep Cover Gecko 57 HSV Adventure Racing 58 Hybrid Heaven 59 Bass Hunter 64 60 Indy Racing 2000 61 Jeremy McGrath Super 62 Jikkyou Powerful Pro Yakyuu 2000 63 Killer Instinct Gold 64 Mace - The Dark Age 65 Mario Kart 64 66 Mickey no Racing Challenge USA 67 Mission Impossible 68 Monaco Grand Prix 69 Mortal Kombat 4 70 Ms. -

Digital Narratives and Linguistic Articulations of Mexican Identities in Emergent Media: Race, Lucha Libre Masks and Mock Spanish

Digital Narratives and Linguistic Articulations of Mexican Identities in Emergent Media: Race, Lucha Libre Masks and Mock Spanish Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Calleros Villarreal, Daniel Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 17:44:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565891 Digital Narratives and Linguistic Articulations of Mexican Identities in Emergent Media: Race, Lucha Libre Masks and Mock Spanish by Daniel Calleros Villarreal ____________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH & PORTUGUESE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2015 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Sara Jones, titled Optical Lens Design and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: Malcolm A. Compitello _______________________________________________________________________ Date: Kenneth S. McAllister _______________________________________________________________________ -

Game Review: Tekken 2

Clifhrd Chao STS 145 21 18/0 1 Game Review: Tekken 2 fimt mers in the arcade and console game markets. To compete against their long-tiule rival the word Tekken meaning “Iron Fist” in Japanese. The series has always boasted unique character skillful fighting engine, all of which makes ittoday the most popular 3-d fighterin the US. in the arcades by the Suxxner of 1995, and later brought to the Sony Playstation in March of outstanding Tekken team, wihich has baen responsible for every veaion of the game since its Tekken. Tekken was created with one underlying goal: to grasp &e piayer’s ego and #rive him or presentation, character designs and even its story are of central importance. However, first and reflex-based game play. Te&m is himy strategic, with various styles of play md lnrind games memust use to ddbat another qqmnmt. Tekken’s graphics,back in its time, were extrmely impressive. The game ran at a Fighter lacked (the poiygons only had one flat color). In terms of presentation, Tekken’s fights are relatively realistic, with moves motion captured from actual martial artists. However, a lot of special effects, flashy throws, explosive hits and attacks which launchan opponent off the ground make the gam much more appding to watch and impI.cssivc thm a compktdy rdi&c G&t. ;w *is sw<cs io grzb 2ild kc* phyix’s *est, mid &iv%hi, fir %a ta +urn, to pdam &csc psi;lfu-lmbg rn0VGS cEccti-Gkf agakist 0pnmts. Mso key is the game’s chmwtm d&gm md sturyb. -

Operator's Manual

Operator’s Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 .O SPECIFICATIONS.. ......................................................................................................... 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION.. ........................................................................................................... 2 2.1 GAME PLAY.. ....................................................................................................... 3 2.2 MAXIMIZING EARNINGS ..................................................................................... 3 3.0 PRECAUTIONS............................................................................................................... 4 3.1 INSTALLATION ....................................................................................................4 3.2 HANDLING.. ......................................................................................................... 4 4.0 INSTALLATION ............................................................................................................... 5 5.0 TEST MODE.. .................................................................................................................. 6 5.1 TEST MODE PROCEDURE ................................................................................. 6 5.2 TEST MENU.. ....................................................................................................... 6 5.2.1 Coin Options ........................................................................................... 7 5.2.2 Game Options ........................................................................................ -

Tekken Jump 1.0. by Fancyfiredrake Welcome to the King of Iron Fist

Tekken Jump 1.0. By FancyFireDrake Welcome to the King of Iron Fist Tournament Jumper! The World of Tekken is one where Devils roam among Mortals, corporations fund Tournaments and chances are you have the most messed up Family this side of fiction. The major plot of this World surrounds the Mishima family and the eternal power struggle between its members. All gunning for either Power or revenge. This conflict has spiralled out of control with the inclusion of Devils and World spanning Wars. Countless of lives have been involved in this never- ending Fight, from your average human with martial art skills to things like enhanced animals, aliens and robots. You have 10 years in this World. Fight well, avoid Volcanoes and perhaps you can become the new King of Iron Fist. Here are your 1000 CP. Use them well. Timeline First, we need to clarify at what point in the timeline you wish to start. There are so far 7 major King of Iron Fist tournaments which we will use to create an understanding of what time you will start your 10 years in. Tekken 1: The first King of Iron Fist Tournament. Kazuya Mishima, son of Heihachi Mishima, has entered to get revenge on the Father that tried to kill him. A dark power has risen inside the youngest Mishima and the Battle between him and Heihachi will give birth to the most destructive legacy in this World. Tekken 2: Heihachi Mishima survived… and he is back for revenge. Two years after the events of Tekken, Father and son will clash once more but the Power inside of Kazuya has started to consume him. -

Trucchi Tekken 5 Per Playstation 2

www.gamestorm.it/PS2 Trucchi Tekken 5 per Playstation 2 NB. i trucchi presenti in questo documento non sono tutti garantiti come funzionanti Se vuoi aggiungere un trucco a questo documento o segnalare un trucco non funzionante visita www.gamestorm.it/PS2! agg. 5 Apr 2013 11:46:37 mossa potente di devil jin inserito in data 20-03-2007 durante il combattimento tenete premuto + e e si caricherà un pugno fortissimo by pigi sbloccare devil jin inserito in data 20-03-2007 uno dei modi più semplici per sbloccare devil jin è finire il gioco 15 volte con personaggi diversi. by Quaranta guadagnare molti soldi in modalità arcade inserito in data 13-11-2006 per guadagnare più di 1000 g a combattimento,scegliete avversari con un livello superiore al vostro,più sarà la differenza di livello,più soldi guadagnerete per quel combattimento by davide. Schiaccia la rana inserito in data 25-09-2006 Nello stage dove c’è un cerchio di fiori rossi al centro(non quello di notte con i fiori bianchi) li vicino c’è una rana e se un personaggio ci finisce sopra cadendo si vedraà il suo spirito con l’aureola salire nel cielo. by Tira mossa con jin inserito in data 27-07-2006 premere con decisione + by Zio Bob mossa di jack5 inserito in data 12-07-2006 (tenuto premuto) by Zio Bob altra mossa con jack5 inserito in data 12-07-2006 (tenuto premuto) + by Zio Bob mossa di jack5 inserito in data 12-07-2006 by Zio Bob altra mossa di raven inserito in data 10-07-2006 (tenuti premuti) e + by Zio Bob mossa di raven inserito in data 10-07-2006 (tenuti premuti)e + by Zio Bob Più soldi in arcade Mode inserito in data 01-07-2006 Dopo aver raggiunto un livello abbastanza alto con un singolo personaggio(es divinità) ricominciate l’arcade con lo stesso personaggio.Il vostro primo avversario dovrebbe avere il vostro stesso rank.Fatevi battere e poi cambiate personaggio scegliendo uno a livello principiante.Battete l’avversario e poi uscite.Ripete il procedimento per avere sempre parecchi crediti. -

Tekken Mac Download

Tekken Mac Download Tekken Mac Download 1 / 5 2 / 5 CoolROM com's game information and ROM download page for Tekken (World, TE4/VER. 1. tekken 7 2. tekken mobile 3. tekken 1 Search Tekken in Google Play Store and find the game in the results that show up.. If you love action apps then this one is really promising for you Bandai Namco recently announced TEKKEN Mobile, which we believed is the first time the arcade and console brawler has made its official fighting.. Tekken Mac Download VersionInstall Tekken 3Tekken Tag Tournament 2 Mac DownloadTekken 7 for macOS DOWNLOAD.. Download Tekken 6 ROM for Playstation Portable(PSP ISOs) and Play Tekken 6 Video Game on your PC, Mac, Android or iOS device! Categories PSP Games For Android Tags tekken 7 iso download for android, tekken 7 pkdownloads, tekken 7 rar download Post navigation GTA 3 Apk Download With Data Highly Compressed Max Payne Apk Download With Data Obb.. Right now this game is available to download as dmg Once dmg file is downloaded, open it and extract the game in applications folder. tekken 7 tekken 7, tekken 3, tekken 1, tekken movie, tekken 6, tekken characters, tekken tag tournament 2, tekken 8, tekken 5, tekken 2, tekken mobile ApQualizr V2.1.0 For MacOS 39 GBDeveloper: NamcoRelease date: 2006Interface language: EnglishTablet: Not requiredPlatform: Intel only To bookmarksTekken 5: Dark Resurrection (鉄拳5 DARK RESURRECTION) (Tekken: Dark Resurrection for the PSP version) is a fighting video game and an update to the PlayStation 2 game Tekken 5.. How to download TEKKEN on PC, Windows and Mac Ali Zain August 23, 2017 ANDROID/IOS APPS FOR PC, HOW TO This app is full of Action.