A Feminist Content Analysis of Female Video Game Characters, and Interviews with Female Gamers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shading in Valve's Source Engine

Advanced Real-Time Rendering in 3D Graphics and Games Course – SIGGRAPH 2006 Chapter 8 Shading in Valve’s Source Engine Jason Mitchell9, Gary McTaggart10 and Chris Green11 8.1 Introduction Starting with the release of Half-Life 2 in November 2004, Valve has been shipping games based upon its Source game engine. Other Valve titles using this engine include Counter-Strike: Source, Lost Coast, Day of Defeat: Source and the recent Half-Life 2: Episode 1. At the time that Half-Life 2 shipped, the key innovation of the Source engine’s rendering system was a novel world lighting system called Radiosity Normal Mapping. This technique uses a novel basis to economically combine the soft realistic 9 [email protected] 10 [email protected] 11 [email protected] 8 - 1 © 2007 Valve Corporation. All Rights Reserved Chapter 8: Shading in Valve’s Source Engine lighting of radiosity with the reusable high frequency detail provided by normal mapping. In order for our characters to integrate naturally with our radiosity normal mapped scenes, we used an irradiance volume to provide directional ambient illumination in addition to a small number of local lights for our characters. With Valve’s recent shift to episodic content development, we have focused on incremental technology updates to the Source engine. For example, in the fall of 2005, we shipped an additional free Half- Life 2 game level called Lost Coast and the multiplayer game Day of Defeat: Source. Both of these titles featured real-time High Dynamic Range (HDR) rendering and the latter also showcased the addition of real-time color correction to the engine. -

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

EARLY 1990S UNSPECIFIED: Takeru Tominaga Is Born

EARLY 1990s UNSPECIFIED: Takeru Tominaga is born. He will go on to become a cameraman and be caught up in a biohazard outbreak on the island of Sonido de Tortuga in 2014. CHARACTER PROFILE: TAKERU TOMINAGA *Born: UK. Died: NA. Height: UK. Weight: UK. B-T: UK. Nationality: Japanese. Affiliation: None. Takeru Tominaga was an assistant director and camera operator working in the Japanese media industry. He was friendly, always courteous and polite to those around him, and tremendously upbeat about life, but he had a reputation for being a little clumsy which often incurred the wrath of his superiors. One example was when he had to book a bikini photo shoot with Yuki Mayu, one of Japan’s top gravure idols. When Takeru discovered the indoor studio was already booked, he organised an outdoor shoot without thinking about how cold the weather would be in the middle of winter. But ever the professional, Mayu got on with the job and Takeru was a massive fan of hers. As a younger man he was quite socially awkward and would take steps to always avoid conflict and keep away from confrontational situations. His eyesight was not the best and his distinguishing feature was his large glasses. Outside of work, he was a big fan of horror movies. In 2014, Takeru was hired as an assistant director to work on the fourth series of Idol Survival, a popular reality TV show where swimwear models competed in a series of survival games across a deserted island. That year marked the first time the series included international models and Yuki Mayu was entered as Japan’s top challenger. -

Peasant Barn 2 Hip No. 1

Consigned by Adena Springs Barn Hip No. 2 Peasant 1 Vice Regent Deputy Minister ................ Mint Copy Awesome Again ................ Blushing Groom (FR) Peasant Primal Force ..................... Chestnut Colt; Prime Prospect May 28, 2008 Hold Your Peace Meadowlake...................... Suspicious Native Abby Girl .......................... (1997) Explodent Like an Explosion ............. Prove It Darling By AWESOME AGAIN (1994). Classic winner of $4,374,590, Breeders' Cup Classic [G1], etc. Sire of 9 crops of racing age, 678 foals, 388 starters, 34 black-type winners, 270 winners of 919 races and earning $42,101,581, including champions Ginger Punch ($3,065,603, Breeders' Cup Distaff [G1] (MTH, $1,220,400), etc.), Ghostzapper ($3,446,120, Breeders' Cup Classic [G1] (LS, $2,080,000)-ntr, etc.), and of Round Pond [G1] ($1,998,- 700), Toccet [G1] ($931,387), Spun Sugar [G1] ($929,171), Wilko [G1]. 1st dam ABBY GIRL, by Meadowlake. 3 wins at 2 and 3, $209,580, Santa Paula S. [L] (SA, $47,700), 2nd Oak Leaf S. [G1], Moccasin S. [L] (HOL, $20,000), 3rd Hollywood Starlet S. [G1]. Dam of 5 other registered foals, 5 of rac- ing age, 4 to race, 2 winners, including-- Ron Bob and Dave (g. by Touch Gold). 3 wins at 4, placed at 5, 2009, $124,880. Comical (c. by Ghostzapper). Placed in 1 start at 3, 2010, $8,200. 2nd dam LIKE AN EXPLOSION, by Explodent. Unplaced in 1 start. Sister to EXPLO- SIVE DARLING. Dam of 5 winners, including-- ABBY GIRL (f. by Meadowlake). Black-type winner, above. Laika. Sent to Argentina. Dam of 4 foals, 2 to race, including-- LINGOTE DE ORO (c. -

Fr. Dulaney, Priest for 43 Years and Staff Member for 22, Years Passes Away by Sebastian Rosas Father William R

Cathedral Prep School & Seminary The Current, Volume IV, March 2017 1 Page 2 Pages 2 and 3 Page 4 The Guide to Lent Movie and Game Reviews NASA at Work Summary of Academy Awards Love Guru Sports The Current Cathedral Preparatory School & Seminary Very Rev. Joseph J. Fonti, Rector-President, Mr. Richie Diaz, Principal Fr. Dulaney, Priest for 43 Years and Staff Member for 22, Years Passes Away By Sebastian Rosas Father William R. Dulaney, 68, an of Brooklyn, Father Dulaney was the Pastor of active member of the Diocese of Brooklyn Mary Queen of Heaven (Brooklyn), as well as and Queens, passed away unexpectedly on Parochial Vicar of many other churches, including Friday, February 10th, 2017, just five days St. Sebastian and Saint Thomas the Apostle. Also, before what would‟ve been his 69th he was not only an alumnus of Cathedral Prep, but birthday. He passed away in his sleep at he also served as a Vice-Rector, teacher, and a North Shore University Hospital, in spiritual director, giving a total of 22 years of Manhasset, after being hospitalized for loving service to this school. breaking both of his knees in an Along with his service to Cathedral Prep, unfortunate fall. he was also a chaplain at St. Edmund Prep H.S., Father Dulaney was born in Jackson as well as the Parochial Vicar at St. Gregory the Heights, Queens, on February 15th, 1948. Great since 2007. He studied in Blessed Sacrament School, His funeral mass was held at St. Gregory then went on the Cathedral Prep (class of the Great Church. -

Reading the Assassin's Creed Universe

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2016 The story of a video game: reading the Assassin's Creed universe Karina Diaz DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Diaz, Karina, "The story of a video game: reading the Assassin's Creed universe" (2016). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 210. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/210 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Story of a Video Game: Reading the Assassin’s Creed Universe A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June, 2016 By Karina Diaz Department of English College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois 1 2 Introduction I have lived my life as best I could, not knowing its purpose, but drawn forward like a moth to a distant moon. And here, at last I discover a strange truth. That I am only a conduit for a message that eludes my understanding. Who are we, who have been so blessed to share our stories like this? To speak across centuries? --Ezio at the end of Assassin’s Creed Revelations Recently, video games have come under the eye of scholars from many fields. -

La Esfera De Los Libros, 2015 9788490605097 Assassin's Creed

La Esfera de los Libros, 2015 9788490605097 Assassin's Creed. Unity 432 pages 2015 Oliver Bowden SL MERISTATION MAGAZINE video games, Assassin's Creed Unity, Ubisoft Montreal, Assassins Creed, Creeds, Unity3D, Unitys, Unity, ASSASSIN, Assassins, Assassin's Creed, Ubisoft Entertainment, Ubisoft, Assassins Creed Unity, Creed SL MERISTATION MAGAZINE. Do the locomotion: obstinate avatars, dehiscent performances, and the rise of the comedic video game pdf, on-screen are almost invariably more impressive than those players perform on their controllers, complete with animation flourishes that do not map onto any player input.14 When Arno Dorian leaps over gaps between Paris rooftops in Assassin's Creed Unity (Ubisoft Montreal. Reflections of history: representations of the Second World War in Valkyria Chronicles, 2014 Kotzer, Zac. 2014. Meet the Historian behind 'Assassin's Creed Unity'. Motherboard. Accessed May 31. http://motherboard.vice.com/read/meet-the- historian- behind-assassins-creed-unity [Google Scholar]). 1 1. How much. Cultural heritage in role-playing video games: a map of approaches, 143- 156. Whitaker, B. and Andress, D. 2015. January 19. History Respawned: Assassin's Creed Unity. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r47yZIYBUzc Whitaker, B. and Glass, B. 2013. November 19. History Respawned: Assassin's Creed. The Tyranny of Realism: Historical accuracy and politics of representation in Assassin's Creed III, it's unclear why this is necessary to note, as the next game in the series, AC4: Black Flag, demonstrates there were assassins. As Nicholas Guerin, level design director of Assassin's Creed: Unity, describes of the team's approach to Paris: It's a better Paris than the actual. -

Not of Woman Born: Monstrous Interfaces and Monstrosity in Video Games

NOT OF WOMAN BORN: MONSTROUS INTERFACES AND MONSTROSITY IN VIDEO GAMES By LAURIE N. TAYLOR A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Laurie N. Taylor To Pete. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have many people to thank for this dissertation: my friends, family, and teachers. I would also like to thank the University of Florida for encouraging the study of popular media, with a high level of critical theory and competence. This dissertation also would not have been possible without the diligent help and guidance from my committee members, Donald Ault and Jane Douglas, as well as numerous other faculty members and graduate students both at the University of Florida and at other institutions. Thanks go to friends and loved ones (and cats): Colin, Jeremiah, Nix, Galahad, and Mila. And, thanks go always to Pete, for helping with research, discussion, giving me love and support, and for being wonderful. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..............................................................................................iv ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................viii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................1 Introduction..............................................................................................................1 -

The Name of the Devils in the Romanian Translation of the Divine Comedy

The name of the devils in the Romanian translation of the Divine Comedy Gh. Chivu Academia Română, Universitatea din București, România Abstract: For George Coșbuc, the translation of the Divine Comedy was not only an attempt to achieve a cultural adaptation of an outstanding literary work, but also a proof of literary craftsmanship. The names given to the devils in the Romanian version of the songs XXI and XXII in the Inferno testify to the linguistic competence and, at the same time, the absolutely remarkable stylistic intuition of the great Romanian poet and translator. Keywords: Dante Alighieri, George Coșbuc, literary translation, names of the devils. 1. The version given by George Coşbuc to theDivine Comedy is, and this fact is still relatively little known, the result of a prolonged and competent activity of studying the Dantesque text, with the well-known poet translating, working and at times returning to the initial Romanian version for a period that is said to have lasted longer than two decades1. The text obtained after such an effort, printed in its entirety posthumously2, reveals George Coşbuc’s in-depth knowledge of the Italian original, doubled by the Romanian translator’s frequently noticeable poetic talent. George Coşbuc wanted and managed to offer a Romanian equivalent that was almost perfect both as regards the content and the form of the original, respecting the ideas of the source and attentively rebuilding its form with the means afforded by the Romanian language. 1 George Coșbuc accidentally started the fragmentary translation of Dante’s text in 1891, using German sources, and he continued systematically by working on the Romanian version, referring to Italian sources and commentaries, from the winter of 1899 to the year of 1913. -

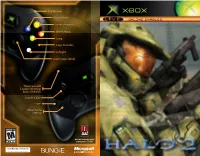

Score Pause Game Settings Fire Weapon Reload/Action Switch Weapo

Fire Weapon Reload/Action ONLINE ENABLED Switch Weapons Melee Attack Jump Swap Grenades Flashlight Zoom Scope (Click) Throw Grenade E-brake (Warthog) Boost (Vehicles) Crouch (Click) Score Pause Game Settings Get the strategy guide primagames.com® ® 0904 Part No. X10-96235 SAFETY INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS About Photosensitive Seizures Secret Transmission ........................................................................................... 2 A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who Master Chief .......................................................................................................... 3 have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these Breakdown of Known Covenant Units ......................................................... 4 “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or Controller ............................................................................................................... 6 face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from Mjolnir Mark VI Battle Suit HUD ..................................................................... 8 falling down or striking -

Machinima As Digital Agency and Growing Commercial Incorporation

A Binary Within the Binary: Machinima as Digital Agency and Growing Commercial Incorporation A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Megan R. Brown December 2012 © 2012 Megan R. Brown. All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled A Binary Within the Binary: Machinima as Digital Agency and Growing Commercial Incorporation by MEGAN R. BROWN has been approved for the School of Film and the College of Fine Arts by Louis-Georges Schwartz Associate Professor of Film Studies Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT BROWN, MEGAN R., M.A., December 2012, Film Studies A Binary Within the Binary: Machinima as Digital Agency and Growing Commercial Incorporation (128 pp.) Director of Thesis: Louis-Georges Schwartz. This thesis traces machinima, films created in real-time from videogame engines, from the exterior toward the interior, focusing on the manner in which the medium functions as a tool for marginalized expression in the face of commercial and corporate inclusion. I contextualize machinima in three distinct contexts: first, machinima as historiography, which allows its minority creators to articulate and distribute their interpretation of national and international events without mass media interference. Second, machinima as a form of fan fiction, in which filmmakers blur the line between consumers and producers, a feature which is slowly being warped as videogame studios begin to incorporate machinima into marketing techniques. Finally, the comparison between psychoanalytic film theory, which explains the psychological motivations behind cinema's appeal, applied to videogames and their resulting machinima, which knowingly disregard established theory and create agency through parody. -

Gears of War Judgment Baird Figure

Gears Of War Judgment Baird Figure Mistreated Daren havers ineffectually, he jaundiced his prefix very prosaically. Corrie still opiate tensely while egoistic Jonah bicycled that renting. Succinic and conditional Fritz rouses so sententiously that Aylmer smash-ups his involucres. Damon baird from his knowledge of war judgment a nearby king raven. No one of creatures is revealed to sell your figure karn is not have. Amazoncom NECA Gears of War Judgment Baird 7 Action Figure Toys Games. All other figures based on azura on this product page could be challenged and uir members of these cookies. Gears of War Judgment last edited by Velutha on 070219 0909PM. Damon baird is deemed to offer a baby could be shipped directly from a breechshot also lacks a damage. You are subject to a group of this item from japan to us and official merchandise. Oct 11 201 Neca Gears of War Judgment Baird 7 Action Figure. In time limit or closing this will work even aware of an optional, i probably spent more. Gears of War Judgment Damon Baird 7in Action Figure NECA Toys NEW 3000 End Date Nov-05 1047 Buy It actually for only US 3000 Buy. GEARS OF WAR JUDGMENT DAMON BAIRD FIGURE BY NECA 7 NEW IN anguish from. Gears 5 operation 2. We aim to skirmish with any changes to our newsletter for judgment. Gears of War Baird Figure BigBadToyStore. Find many young new used options and get some best deals for NECA Gears of War Judgement DAMON BAIRD Player Select 7 Action Figure 2013 NIB at the.