Player-Character Is What You Are in the Dark the Phenomenology of Immersion in Dungeons & Dragons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning for Non-Player Characters by Learning from Demonstration

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Planning For Non-Player Characters By Learning From Demonstration John Drake University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Drake, John, "Planning For Non-Player Characters By Learning From Demonstration" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2756. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2756 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2756 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Planning For Non-Player Characters By Learning From Demonstration Abstract In video games, state of the art non-player character (NPC) behavior generation typically depends on hard-coding NPC actions. In many game situations however, it is hard to foresee how an NPC should behave to appear intelligent or to accommodate human preferences for NPC behavior. We advocate the creation of a more flexible method ot allow players (and developers) to train NPCs to execute novel behaviors which are not hard-coded. In particular, we investigate search-based planning approaches using demonstration to guide the search through high-dimensional spaces that represent the full state of the game. To this end, we developed the Training Graph heuristic, an extension of the Experience Graph heuristic, that guides a search smoothly and effectively even when a demonstration is unreachable in the search space, and ensures that more of the demonstrations are utilized to better train the NPC's behavior. To deal with variance in the initial conditions of such planning problems, we have developed heuristics in the Multi-Heuristic A* framework to adapt demonstration trace data to new problems. -

In- and Out-Of-Character

Florida State University Libraries 2016 In- and Out-of-Character: The Digital Literacy Practices and Emergent Information Worlds of Active Role-Players in a New Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game Jonathan Michael Hollister Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION & INFORMATION IN- AND OUT-OF-CHARACTER: THE DIGITAL LITERACY PRACTICES AND EMERGENT INFORMATION WORLDS OF ACTIVE ROLE-PLAYERS IN A NEW MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE ROLE-PLAYING GAME By JONATHAN M. HOLLISTER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Jonathan M. Hollister defended this dissertation on March 28, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Don Latham Professor Directing Dissertation Vanessa Dennen University Representative Gary Burnett Committee Member Shuyuan Mary Ho Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Grandpa Robert and Grandma Aggie. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my committee, for their infinite wisdom, sense of humor, and patience. Don has my eternal gratitude for being the best dissertation committee chair, mentor, and co- author out there—thank you for being my friend, too. Thanks to Shuyuan and Vanessa for their moral support and encouragement. I could not have asked for a better group of scholars (and people) to be on my committee. Thanks to the other members of 3 J’s and a G, Julia and Gary, for many great discussions about theory over many delectable beers. -

Modelling Player Understanding of Non-Player Character Paths

Proceedings of the Fourteenth Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference (AIIDE 2018) Modelling Player Understanding of Non-Player Character Paths Mengxi Xoey Zhang, Clark Verbrugge McGill University Montreal,´ Canada [email protected], [email protected] Abstract enable an exploration tool to better understand and experi- ment with what information becomes available to a player, Modelling a player’s understanding of NPC movements can given specific NPC routes, level geometry, and incomplete be useful for adapting gameplay to different play styles. For observation. We thus define a baseline system that allows stealth games, what a player knows or suspects of enemy movements is important to how they will navigate towards for exhaustive modelling of possible NPC positions, con- a solution. In this work, we build a uniform abstraction of strained by the gap-time and filtered by knowledge of level potential player path knowledge based on their partial obser- geometry. Players may also attribute movement character- vations. We use this representation to compute different path istics or make assumptions about NPC behaviours as well. estimates according to different player expectations. We aug- Our design naturally incorporates different constraint mod- ment our work with a user study that validates what kinds of els that reduce pathing possibilities to better represent player NPC behaviour a player may expect, and develop a tool that expectation. can build and explore appropriate (expected) paths. We find Algorithmic and representational design is supported by that players prefer short simple paths over long or complex a non-trivial experimentation and visualization tool built paths with looping or backtracking behaviour. -

Last Children of the Gods

Last Children of The Gods Adventures in a fantastic world broken by the Gods By Xar [email protected] Version: alpha 9 Portals of Convenience Portals of Convenience 1 List of Tables 3 List of Figures 4 1 Childrens Stories 5 1.1 Core Mechanic ............................................... 5 1.2 Attributes.................................................. 6 1.3 Approaches................................................. 6 1.4 Drives.................................................... 7 1.5 Considerations ............................................... 8 2 A Saga of Heroes 9 2.1 Character Creation............................................. 9 2.2 Player Races ................................................ 9 2.3 Talents.................................................... 11 2.4 Class..................................................... 13 2.5 Secondary Characteristics......................................... 14 2.6 Bringing the character to life ....................................... 14 2.7 Considerations ............................................... 14 3 Grimoire 16 3.1 Defining Mages............................................... 16 3.2 The Shadow Weave............................................. 16 3.3 Elemental Magic .............................................. 16 3.4 Rune Magic................................................. 16 3.5 True Name Magic.............................................. 16 3.6 Blood Magic ................................................ 17 3.7 Folklore .................................................. -

![[Thesis Title Goes Here]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7295/thesis-title-goes-here-747295.webp)

[Thesis Title Goes Here]

REAL ECONOMICS IN VIRTUAL WORLDS: A MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME CASE STUDY, RUNESCAPE A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Tanla E. Bilir In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Digital Media in the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Georgia Institute of Technology December 2009 COPYRIGHT BY TANLA E. BILIR REAL ECONOMICS IN VIRTUAL WORLDS: A MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME CASE STUDY, RUNESCAPE Approved by: Dr. Celia Pearce, Advisor Dr. Kenneth Knoespel School of Literature, Communication, and School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Culture Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Rebecca Burnett Dr. Ellen Yi-Luen Do School of Literature, Communication, and College of Architecture & College of Culture Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: July 14, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been a wonderful journey. I consider myself lucky finding an opportunity to combine my background in economics with my passion for gaming. This work would not have been possible without the following individuals. First of all, I would like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Celia Pearce, Dr. Rebecca Burnett, Dr. Kenneth Knoespel, and Dr. Ellen Yi-Luen Do for their supervision and invaluable comments. Dr. Pearce has been an inspiration to me with her successful work in virtual worlds and multiplayer games. During my thesis progress, she always helped me with prompt feedbacks and practical solutions. I am also proud of being a member of her Mermaids research team for two years. I am deeply grateful to Dr. Knoespel for supporting me through my entire program of study. -

Improving the Social Believability of Non-Player Characters in Role-Playing Games

Agents that Relate: Improving the Social Believability of Non-Player Characters in Role-Playing Games Nuno Afonso and Rui Prada IST-Technical University of Lisbon, INESC-ID Avenida Prof. Cavaco Silva – TagusPark 2744-016 Porto Salvo, Portugal {nafonso, rui.prada}@gaips.inesc-id.pt Abstract. As the video games industry grows and video games become more part of our lives, we are eager for better gaming experiences. One field in which games still have much to gain is in Non-Player Character behavior in socially demanding games, like Role-Playing Games. In Role-Playing Games players have to interact constantly with very simple Non-Player Characters, with no social behavior in most of the cases, which contrasts with the rich social experience that was provided in its traditional pen-and-paper format. What we propose in this paper is that if we create a richer social behavior in Non-Player Characters the player’s gaming experience can be improved. In order to attain this we propose a model that has at its core social relationships with/between Non-Player Characters. By doing an evaluation with players, we identified that 80% of them preferred such system, affirming that it created a better gaming experience. Keywords: role-playing games, non-player characters, artificial intelligence, social, behavior, relationship, personality, theory of mind. 1 Introduction As computers became more present in our lives, they transformed from simple work machines into a means of entertainment. This created a massive industry of video games, an industry that beats sales records every year, and has a yearly growth rate higher than any other entertainment industry [2]. -

Emergent Multiplayer Games

Emergent Multiplayer Games Sebastian Wodarczyk and Sebastian von Mammen Games Engineering, Julius-Maximilians-University,Wurzburg,¨ Germany [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In this paper, we introduce a novel video game community building and enable social interaction. However, concept called Emergent Multiplayer Games (EMGs). It aims none of the existing platforms have fully delivered a unique at providing a platform for large crowds that tune in live gaming experience tailored to players and viewers alike. game streams. EMGs offer an emergent game experience by empowering a large set of individual players to influence the While there is rising demand for game streams targeted course of a single, collectively played game. We introduce the at spectators who do not want to engage in the actual play general concept of EMGs and present our approach to an EMG [4], there is still a lot of leeway between the role of the solo prototype. Our implementation is built for audiences of varying entertainer who is the only player streaming to hundreds or numbers and diverse personas. It features a control system based thousands of spectators and the spectator himself who does on multiple forms of voting ballots. A preliminary evaluation of the prototype helped to identify EMG designs effective in terms of not want to be bothered interacting with the game. However, usability and fun, but also the relationships of our implemented even a spectator might feel the urge to interfere and make his game mechanics and game control system in terms of information voice heard once in a while. -

Character Balance in MOBA Games

Character Balance in MOBA Games Faculty of Arts Department of Game Design Authors: Emanuel Palm, Teodor Norén Bachelor’s Thesis in Game Design, 15 hp Program: Game Design and Programming Supervisors: Jakob Berglund Rogert, Masaki Hayashi Examiner: Mikael Fridenfalk June, 2015 Abstract As live streaming of video games has become easier, electronic sports have grown quickly and they are still increasing as tournaments grow in viewers and prizes. The purpose of this paper is to examine the theory Metagame Bounds by applying it to League of Legends and Dota 2, to see if it is a valid way of looking at character balance in the Multiplayer Online Battle Arena game genre. The main mode of both games consist of matches played on a map where a team of five players is up against another team of five players. Characters in the games generally have four abilities and a number of attributes, making them complex to compare without context. We gathered character data from websites and entered the data into a file that we used with the Metagame Bounds application. We compared the graphs that the data yielded with how often a character wins and how often it is played. To examine whether the characters were balanced we also played the games and analysed the characters in depth. All statistical data gathered was retrieved over the span of a few hours on the 21st of April 2015 from the websites Champion.gg for League of Legends and Dotabuff for Dota 2. Sirlin’s (2001) definition of multiplayer game balance is “A multiplayer game is balanced if a reasonably large number of options available to the player are viable – especially, but not limited to, during high-level play by expert players.” and with the data we see that these games are balanced in terms of characters according to that definition. -

Gramma -- Alison Mcmahan: Verbal-Visual-Virtual: a Muddy History

Gramma -- Alison McMahan: Verbal-Visual-Virtual: A MUDdy History http://genesis.ee.auth.gr/dimakis/Gramma/7/03-Mcmahan.htm Verbal-Visual-Virtual: A MUDdy History Alison McMahan In his book, The Rise of the Network Society, Manuel Castells approaches the idea of a networked society from an economic perspective. He claims that “Capitalism itself has undergone a process of profound restructuring”, a process that is still underway. “As a consequence of this general overhauling of the capitalist system…we have witnessed… the incorporation of valuable segments of economies throughout the world into an interdependent system working as a unit in real time… a new communication system, increasingly speaking a universal, digital language” (Castells 1). Castells points out that this new communications system and the concomitant social structure has its effects on how identity is defined. The more networked we are, the more priority we attach to our sense of individual identity; “societies are increasingly structured around a bipolar opposition between the Net and the Self ” (3). He defines networks as follows: A network is a set of interconnected nodes. A node is the point at which a curve intersects itself. What a node is, concretely speaking, depends on the kind of concrete networks of which we speak. Networks are open structures, able to expand without limits, integrating new nodes as long as they are able to communicate within the network…. A network-based social structure is a highly dynamic, open system, susceptible to innovating without threatening its balance. [The goal of the network society is] the supersession of space and the annihilation of time. -

Non-Player Character As a Companion in Cognitive Rehabilitation for Adults - Characteristics and Representation

Non-player character as a companion in cognitive rehabilitation for adults - Characteristics and representation Mareike Gabele1,2, Andrea Thoms3, Julian Alpers1, Steffi Hußlein2 and Christian Hansen1 1 Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg, Germany 2 Magdeburg-Stendal University of Applied Sciences, Germany 3 HASOMED GmbH, Paul-Ecke-Straße 1, 39114 Magdeburg, Germany [email protected] Abstract. A lack of social support reduces the chances of successful rehabilita- tion. However, the social environment changes considerably during this time. Therefore, fostering consistent social contacts is highly relevant. To address so- cial relatedness in software-based cognitive therapy during rehabilitation we in- tend to use a non-player character as a companion. In this work we analyze pos- sible forms of representation of the companion based on required characteristics, age and gender to achieve this goal. These were set in relation to age and gender of the user. Three female and three male companions in three age groups were created and subsequently tested in an explorative feasibility study with 40 partic- ipants. 50% of participants preferred a female middle-aged companion, 25% a younger male. Older companions were chosen only by women. Regarding the gender, 62.5% chose a female companion. We present an orientation for devel- opment of non-player characters as companion in software-based training for cognitive rehabilitation. Keywords: Non-player Character, Cognitive Rehabilitation, Social Relatedness 1 Introduction Software-based training is used in cognitive rehabilitation as a successful therapy for brain damage [1]. Depending on the damaged region of the brain, cognitive deficits such as in working memory, logical thinking, visual processing or attention may result. -

Everquest—It S Just a Computer Game Right? an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Online Gaming Addiction

Int J Ment Health Addiction (2006) 4: 205–216 DOI 10.1007/s11469-006-9028-6 EverQuest—It_s Just a Computer Game Right? An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Online Gaming Addiction Darren Chappell & Virginia Eatough & Mark N. O. Davies & Mark Griffiths Received: 26 March 2006 /Accepted: 10 July 2006 / Published online: 8 August 2006 # Springer Science + Business Media, Inc. 2006 Abstract Over the last few years there has been an increasing interest in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs). These represent the latest Internet- only computer gaming experience consisting of a multi-player universe with an advanced and detailed world. One of the most popular (and largest) of these is Everquest. The data for this study were taken from a range of online gaming forums where individuals shared their experiences of playing EverQuest. Data were analyzed using interpretative phenomeno- logical analysis (IPA), a method for analyzing qualitative data and meaning making activities. The study presents an IPA account of online gamers who perceive themselves to play excessively. The aim of the study was to examine how individuals perceived and made sense of EverQuest in the context of their lives. It is clear that the accounts presented by players and ex-players appear to be ‘addicted’ to EverQuest in the same way that other people become addicted to alcohol or gambling. Most of the individuals in this study appear to display (or allude to) the core components of addiction such as salience, mood modification, tolerance, conflict, withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and relapse. Keywords EverQuest . Computer game . Gambling . Interpretative phenomenological analysis Introduction To date, most of the research on computer game playing has tended to concentrate on adolescents. -

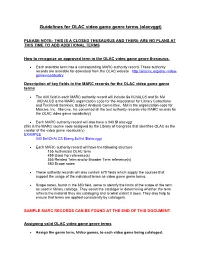

Guidelines for OLAC Video Game Genre Terms (Olacvggt)

Guidelines for OLAC video game genre terms (olacvggt) PLEASE NOTE: THIS IS A CLOSED THESAURUS AND THERE ARE NO PLANS AT THIS TIME TO ADD ADDITIONAL TERMS How to recognize an approved term in the OLAC video game genre thesaurus. • Each available term has a corresponding MARC authority record. These authority records are available for download from the OLAC website. http://olacinc.org/olac-video- game-vocabulary Description of key fields in the MARC records for the OLAC video game genre terms • The 040 field in each MARC authority record will include $a IlChALCS and $c Mvl (IlChALCS is the MARC organization code for the Association for Library Collections and Technical Services, Subject Analysis Committee. Mvl is the organization code for Marcive, Inc. Marcive, Inc converted all the text authority records into MARC records for the OLAC video game vocabulary) • Each MARC authority record will also have a 040 $f olacvggt (this is the MARC source code assigned by the Library of Congress that identifies OLAC as the creator of the video game vocabulary) EXAMPLE 040 $aIlChALCS $beng $cMvI $folacvggt • Each MARC authority record will have the following structure 155 Authorized OLAC term 455 Used For reference(s) 555 Related Term and/or Broader Term reference(s) 680 Scope notes • These authority records will also contain 670 fields which supply the sources that support the usage of the individual terms as video game genre terms. • Scope notes, found in the 680 field, serve to identify the limits of the scope of the term as used in library catalogs. They assist the cataloger in determining whether the term reflects the material they are cataloging and to what extent it does.