The Speed of Player Character Growth Affects Enjoyment And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning for Non-Player Characters by Learning from Demonstration

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Planning For Non-Player Characters By Learning From Demonstration John Drake University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Drake, John, "Planning For Non-Player Characters By Learning From Demonstration" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2756. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2756 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2756 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Planning For Non-Player Characters By Learning From Demonstration Abstract In video games, state of the art non-player character (NPC) behavior generation typically depends on hard-coding NPC actions. In many game situations however, it is hard to foresee how an NPC should behave to appear intelligent or to accommodate human preferences for NPC behavior. We advocate the creation of a more flexible method ot allow players (and developers) to train NPCs to execute novel behaviors which are not hard-coded. In particular, we investigate search-based planning approaches using demonstration to guide the search through high-dimensional spaces that represent the full state of the game. To this end, we developed the Training Graph heuristic, an extension of the Experience Graph heuristic, that guides a search smoothly and effectively even when a demonstration is unreachable in the search space, and ensures that more of the demonstrations are utilized to better train the NPC's behavior. To deal with variance in the initial conditions of such planning problems, we have developed heuristics in the Multi-Heuristic A* framework to adapt demonstration trace data to new problems. -

Player-Character Is What You Are in the Dark the Phenomenology of Immersion in Dungeons & Dragons

Player-Character Is What You Are in the Dark The Phenomenology of Immersion in Dungeons & Dragons William J. White The idea of role-playing makes some people nervous – even some people who play role-playing games (RPGs). Yeah, sure, we pretend to be wizards and talk in funny voices, such players often say. So what? It’s just for fun. It’s not like it means anything. These players tend to find talk about role-playing games being “art” to be pretentious nonsense, and the idea that there could be philosophical value in a game like Dungeons & Dragons strikes them as preposterous on its face. “RPGs as instruction on ethics or metaphysics?” writes one such player in an online forum for discussing role-playing games. “Utter intellectualoid [sic] bullshit … [from those] who want to imagine they’re great thinkers thinking great thoughts while they play RPGs because they’d otherwise feel ashamed about pretending to be an elf.”1 By the same token, people who don’t play RPGs are often quite mystified about what could possibly be going on in a game of Dungeons & Dragons: There’s no board? How do you win? No winners? Then why do you play?2 Making sense of D&D as Dungeons & Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage Copyright © 2014. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. All rights reserved. & Sons, Incorporated. © 2014. John Wiley Copyright on All Wisdom Checks, First Edition. Edited by Christopher Robichaud. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 82 Dungeons and Dragons and Philosophy : Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom Checks, edited by Christopher Robichaud, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2014. -

How to Buy DVD PC Games : 6 Ribu/DVD Nama

www.GamePCmurah.tk How To Buy DVD PC Games : 6 ribu/DVD Nama. DVD Genre Type Daftar Game Baru di urutkan berdasarkan tanggal masuk daftar ke list ini Assassins Creed : Brotherhood 2 Action Setup Battle Los Angeles 1 FPS Setup Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth 1 Adventure Setup Call Of Duty American Rush 2 1 FPS Setup Call Of Duty Special Edition 1 FPS Setup Car and Bike Racing Compilation 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars Mater-National Championship 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars Toon: Mater's Tall Tales 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars: Radiator Springs Adventure 1 Racing Simulation Setup Casebook Episode 1: Kidnapped 1 Adventure Setup Casebook Episode 3: Snake in the Grass 1 Adventure Setup Crysis: Maximum Edition 5 FPS Setup Dragon Age II: Signature Edition 2 RPG Setup Edna & Harvey: The Breakout 1 Adventure Setup Football Manager 2011 versi 11.3.0 1 Soccer Strategy Setup Heroes of Might and Magic IV with Complete Expansion 1 RPG Setup Hotel Giant 1 Simulation Setup Metal Slug Anthology 1 Adventure Setup Microsoft Flight Simulator 2004: A Century of Flight 1 Flight Simulation Setup Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian 1 Action Setup Naruto Ultimate Battles Collection 1 Compilation Setup Pac-Man World 3 1 Adventure Setup Patrician IV Rise of a Dynasty (Ekspansion) 1 Real Time Strategy Setup Ragnarok Offline: Canopus 1 RPG Setup Serious Sam HD The Second Encounter Fusion (Ekspansion) 1 FPS Setup Sexy Beach 3 1 Eroge Setup Sid Meier's Railroads! 1 Simulation Setup SiN Episode 1: Emergence 1 FPS Setup Slingo Quest 1 Puzzle -

In- and Out-Of-Character

Florida State University Libraries 2016 In- and Out-of-Character: The Digital Literacy Practices and Emergent Information Worlds of Active Role-Players in a New Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game Jonathan Michael Hollister Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION & INFORMATION IN- AND OUT-OF-CHARACTER: THE DIGITAL LITERACY PRACTICES AND EMERGENT INFORMATION WORLDS OF ACTIVE ROLE-PLAYERS IN A NEW MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE ROLE-PLAYING GAME By JONATHAN M. HOLLISTER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Jonathan M. Hollister defended this dissertation on March 28, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Don Latham Professor Directing Dissertation Vanessa Dennen University Representative Gary Burnett Committee Member Shuyuan Mary Ho Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Grandpa Robert and Grandma Aggie. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my committee, for their infinite wisdom, sense of humor, and patience. Don has my eternal gratitude for being the best dissertation committee chair, mentor, and co- author out there—thank you for being my friend, too. Thanks to Shuyuan and Vanessa for their moral support and encouragement. I could not have asked for a better group of scholars (and people) to be on my committee. Thanks to the other members of 3 J’s and a G, Julia and Gary, for many great discussions about theory over many delectable beers. -

UPDATE NEW GAME !!! the Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing + Update 1.1.08 Jack Keane 2: the Fire Within Legends of Dawn Pro E

UPDATE NEW GAME !!! The Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing + Update 1.1.08 Jack Keane 2: The Fire Within Legends of Dawn Pro Evolution Soccer 2013 Patch PESEdit.com 4.1 Endless Space: Disharmony + Update v1.1.1 The Curse of Nordic Cove Magic The Gathering Duels of the Planeswalkers 2014 Leisure Suit Larry: Reloaded Company of Heroes 2 + Update v3.0.0.9704 Incl DLC Thunder Wolves + Update 1 Ride to Hell: Retribution Aeon Command The Sims 3: Island Paradise Deadpool Machines at War 3 Stealth Bastard GRID 2 + Update v1.0.82.8704 Pinball FX2 + Update Build 210613 incl DLC Call of Juarez: Gunslinger + Update v1.03 Worms Revolution + Update 7 incl. Customization Pack DLC Dungeons & Dragons: Chronicles of Mystara Magrunner Dark Pulse MotoGP 2013 The First Templar: Steam Special Edition God Mode + Update 2 DayZ Standalone Pre Alpha Dracula 4: The Shadow of the Dragon Jagged Alliance Collectors Bundle Police Force 2 Shadows on the Vatican: Act 1 -Greed SimCity 2013 + Update 1.5 Hairy Tales Private Infiltrator Rooks Keep Teddy Floppy Ear Kayaking Chompy Chomp Chomp Axe And Fate Rebirth Wyv and Keep Pro Evolution Soccer 2013 Patch PESEdit.com 4.0 Remember Me + Update v1.0.2 Grand Ages: Rome - Gold Edition Don't Starve + Update June 11th Mass Effect 3: Ultimate Collectors Edition APOX Derrick the Deathfin XCOM: Enemy Unknown + Update 4 Hearts of Iron III Collection Serious Sam: Classic The First Encounter Castle Dracula Farm Machines Championships 2013 Paranormal Metro: Last Light + Update 4 Anomaly 2 + Update 1 and 2 Trine 2: Complete Story ZDSimulator -

Diablo 1 Windows 10 Download Diablo

diablo 1 windows 10 download Diablo. Diablo is one of the pioneer and classic game of the action role-playing genre. Play this classic game once again, download Diablo on your computer. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10. Role-playing games (RPG) for computers have always had a very important place within the video game market. In the first PC era, these games were, in their vast majority, games that showed everything from a first-person perspective. But all this changed with the arrival of a new batch of RPG games, led by Diablo , action role-playing games . Play one of the most important classic role-playing games once again. The original Diablo game, which was launched in 1997, set a milestone in the video gaming world and specially role-playing games, and was the start of a very important game saga. One of the changes that could be noticed with greater ease in Diablo was the graphics, due to the fact that it used an isometric view , as well as this, the game was also characterized by the fact that it didn't set so much importance on the story, but focused more on the destruction of every single enemy the player encountered. The player was offered three different characters to choose from, each with its own features and equipment: the warrior (powerful in hand-to-hand combat), the rogue (that was especially gifted in the use of bows and crossbows) and the magician (imbued with arcane power to cast spells). Once the player had chosen his/her character and named it, he/she had to decide which features he/she would improve on each level and set out in search of adventure. -

Modelling Player Understanding of Non-Player Character Paths

Proceedings of the Fourteenth Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference (AIIDE 2018) Modelling Player Understanding of Non-Player Character Paths Mengxi Xoey Zhang, Clark Verbrugge McGill University Montreal,´ Canada [email protected], [email protected] Abstract enable an exploration tool to better understand and experi- ment with what information becomes available to a player, Modelling a player’s understanding of NPC movements can given specific NPC routes, level geometry, and incomplete be useful for adapting gameplay to different play styles. For observation. We thus define a baseline system that allows stealth games, what a player knows or suspects of enemy movements is important to how they will navigate towards for exhaustive modelling of possible NPC positions, con- a solution. In this work, we build a uniform abstraction of strained by the gap-time and filtered by knowledge of level potential player path knowledge based on their partial obser- geometry. Players may also attribute movement character- vations. We use this representation to compute different path istics or make assumptions about NPC behaviours as well. estimates according to different player expectations. We aug- Our design naturally incorporates different constraint mod- ment our work with a user study that validates what kinds of els that reduce pathing possibilities to better represent player NPC behaviour a player may expect, and develop a tool that expectation. can build and explore appropriate (expected) paths. We find Algorithmic and representational design is supported by that players prefer short simple paths over long or complex a non-trivial experimentation and visualization tool built paths with looping or backtracking behaviour. -

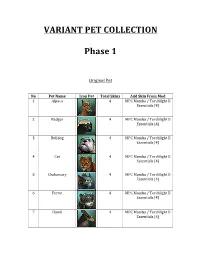

VARIANT PET COLLECTION Phase 1

VARIANT PET COLLECTION Phase 1 Original Pet No Pet Name Icon Pet Total Skins Add Skin From Mod 1 Alpaca 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 2 Badger 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 3 Bulldog 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 4 Cat 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 5 Chakawary 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 6 Ferret 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 7 Hawk 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 8 Headcrap 6 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [6] 9 Owl 11 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [11] 10 Panda 5 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] EV Modpack [1] 11 Panther 11 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [8] Variant Class [3] 12 Papillon 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 13 Stag 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 14 Wolf 7 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] Dire Wolf SynergiesMOD Pet [1] Wolf Pack [2] Add Pets No Pet Name Icon Pet Total Skins Add Mod From 1 Alchemic Construct 2 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [2] 2 Ancient Automaton 2 MPC Mamba [2] 3 Ancient Skeleton 6 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [6] 4 Armadax 3 MPC Mamba [1] Xev Pet [1] Phan Big Pet [1] 5 Armored 1 Phan Big Pet [1] Strumbeorn 6 Armored Warbeast 1 Phan Big Pet [1] [*] 7 Artificer 1 Boss Pet [1] 8 Avatar 1 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [1] 9 Baneling 1 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [1] By: Gao 10 Banshee 3 Anarch Pet / Torchlight II Essentials [3] 11 Basilisk 4 MPC Mamba / Torchlight II Essentials [4] 12 Bat 4 MPC Mamba [4] 13 Bear 5 MPC Mamba [5] By: -

Last Children of the Gods

Last Children of The Gods Adventures in a fantastic world broken by the Gods By Xar [email protected] Version: alpha 9 Portals of Convenience Portals of Convenience 1 List of Tables 3 List of Figures 4 1 Childrens Stories 5 1.1 Core Mechanic ............................................... 5 1.2 Attributes.................................................. 6 1.3 Approaches................................................. 6 1.4 Drives.................................................... 7 1.5 Considerations ............................................... 8 2 A Saga of Heroes 9 2.1 Character Creation............................................. 9 2.2 Player Races ................................................ 9 2.3 Talents.................................................... 11 2.4 Class..................................................... 13 2.5 Secondary Characteristics......................................... 14 2.6 Bringing the character to life ....................................... 14 2.7 Considerations ............................................... 14 3 Grimoire 16 3.1 Defining Mages............................................... 16 3.2 The Shadow Weave............................................. 16 3.3 Elemental Magic .............................................. 16 3.4 Rune Magic................................................. 16 3.5 True Name Magic.............................................. 16 3.6 Blood Magic ................................................ 17 3.7 Folklore .................................................. -

![[Thesis Title Goes Here]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7295/thesis-title-goes-here-747295.webp)

[Thesis Title Goes Here]

REAL ECONOMICS IN VIRTUAL WORLDS: A MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME CASE STUDY, RUNESCAPE A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Tanla E. Bilir In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Digital Media in the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Georgia Institute of Technology December 2009 COPYRIGHT BY TANLA E. BILIR REAL ECONOMICS IN VIRTUAL WORLDS: A MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE GAME CASE STUDY, RUNESCAPE Approved by: Dr. Celia Pearce, Advisor Dr. Kenneth Knoespel School of Literature, Communication, and School of Literature, Communication, and Culture Culture Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Rebecca Burnett Dr. Ellen Yi-Luen Do School of Literature, Communication, and College of Architecture & College of Culture Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: July 14, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been a wonderful journey. I consider myself lucky finding an opportunity to combine my background in economics with my passion for gaming. This work would not have been possible without the following individuals. First of all, I would like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Celia Pearce, Dr. Rebecca Burnett, Dr. Kenneth Knoespel, and Dr. Ellen Yi-Luen Do for their supervision and invaluable comments. Dr. Pearce has been an inspiration to me with her successful work in virtual worlds and multiplayer games. During my thesis progress, she always helped me with prompt feedbacks and practical solutions. I am also proud of being a member of her Mermaids research team for two years. I am deeply grateful to Dr. Knoespel for supporting me through my entire program of study. -

FATE User Guide

TORCHLIGHT User Guide V 1.0 Ember! Merchants prize it for trade. Enchanters distill it for raw magical energy. But a shadowy few crave it for the lure of unsurpassed power and potential immortality. For years the town of Torchlight thrived on these rich deposits of crystallized magic, at least until something else was unearthed in Orden Mines. Now miners fear that recently recovered relics and unusual monsters indicate something or someone tunneled beneath the bedrock long before Torchlight existed. Is it true? Is ember a commodity? Or a curse? Table of Contents Important Stuff to Know Before Reading Further Getting Started System Requirements Installing TORCHLIGHT Installing Direct X Settings Part I: The Tutorial Begin the Adventure Choose Your Character Explore Torchlight Village Select a Quest Exploring with AutoMap Exploring the Mine and Other Underground Places Combat Melee or Close Combat Ranged Combat Artifacts, Gold and Items Dealing with Defeat Part II: Beyond the Tutorial (The Details) The TORCHLIGHT Perspective and Game Menus Take in the Details The Game Interface Using Your Pet Interface during Game Play How to Customize Skills & Items on the Game Interface How to Assign or Replace a Spell in a Spell Slot How to use an Inventory Item Talk Around Torchlight Town Transactions Your Faithful Companion Pet Levels and Attributes How to Fish Stash and Shared Stash Inventories Character Development How to Gain Experience Points and Levels Character Classes and Starting Attributes The Four Attributes of Adventure Strength Dexterity -

Improving the Social Believability of Non-Player Characters in Role-Playing Games

Agents that Relate: Improving the Social Believability of Non-Player Characters in Role-Playing Games Nuno Afonso and Rui Prada IST-Technical University of Lisbon, INESC-ID Avenida Prof. Cavaco Silva – TagusPark 2744-016 Porto Salvo, Portugal {nafonso, rui.prada}@gaips.inesc-id.pt Abstract. As the video games industry grows and video games become more part of our lives, we are eager for better gaming experiences. One field in which games still have much to gain is in Non-Player Character behavior in socially demanding games, like Role-Playing Games. In Role-Playing Games players have to interact constantly with very simple Non-Player Characters, with no social behavior in most of the cases, which contrasts with the rich social experience that was provided in its traditional pen-and-paper format. What we propose in this paper is that if we create a richer social behavior in Non-Player Characters the player’s gaming experience can be improved. In order to attain this we propose a model that has at its core social relationships with/between Non-Player Characters. By doing an evaluation with players, we identified that 80% of them preferred such system, affirming that it created a better gaming experience. Keywords: role-playing games, non-player characters, artificial intelligence, social, behavior, relationship, personality, theory of mind. 1 Introduction As computers became more present in our lives, they transformed from simple work machines into a means of entertainment. This created a massive industry of video games, an industry that beats sales records every year, and has a yearly growth rate higher than any other entertainment industry [2].