Long-Term Soil Productivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deschutes National Forest Memorial Day Weekend 2009

Deschutes National Forest Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update KNOW BEFORE YOU GO! Updated August 12, 2012 Summer Trail Summary Very limited late season snow patches may be found along the Cascade crest. Most not an issue, but you may find a drift or two on north aspects at the higher elevations! Blow down levels on trails range from light to heavy with approximately 65- 70% of Deschutes Trails cleared of blowdown for this season. Mosquitos highly variable. Road 370 still closed by late season snow and muddy sections. Estimated opening, later this week. Metolius River restoration projects in progress with some trail closures or detours likely over coming weeks. South Sister Climbers Trail, Moraine and Green Lakes Trails have a few snow patches remaining. A few down trees have not been cleared from these trails. Dogs must be on leash on these trails thru Sept 15. Northwest Youth Corps installing one of several new hiking bridges on Metolius River Trails. Beware of restoration Be aware that a number of trail projects continuing on Metolius Trails into the Fall. bridges have reached the end of their usable life and have been posted closed to stock use…use nearby ford or alternate route. Go prepared with your Ten Essential Systems: Navigation (map and compass) Sun protection (sunglasses/sunscreen) Insulation (extra clothing) Illumination (headlamp/flashlight) First-aid supplies Fire(waterproofmatches/lighter/candles) Repair kit and tools Late melting snow patch on South Sister Climbers Trail at 6,000’. Photo 8/09/12. Wear boots,Take a map… Nutrition (extra food) GO PREPARED! Hydration (extra water) Emergency shelter Reminder: PLEASE, PRACTICE THE SEVEN LEAVE NO TRACE PRINCIPALS: Plan Ahead and Prepare Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces Dispose of Waste Properly Leave What You Find Minimize Campfire Impacts Respect Wildlife Be Considerate of Other Visitors For details on the 7 LNT Principals: http://lnt.org/learn/7-principles Excerpts from a recent Wilderness Ranger report: Sisters Mirror Lakes continue to see extensive day use. -

Jefferson County General Reports

JEFFERSON COUNT¥ ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY STUDY Geologist (125 days@ $125/day) • $ 15,600 * Editing (65 days@ $77/day) • 5,000 * Cartography. 4,000 * Supplies. • 750 * Printing. • 4,900 Travel and per diem Per diem - $27.50 x 60 days •••••••••• • $1,650 Travel to job - 566 (mi. round trip) x 12 x 14¢. 948 Travel on job - 100 x 60 x 14¢ • • •••• 840 3,438 * Overhead on* items above - $28,788 x 20%. 5,757 TOTAL. • • • $ 39,445 Maps: (1) Geology - 4 or 5 color (1 inch= 3 miles) (2) Mineral deposits (combine with geology?) (3) Urban - 7~' - 1:24,000 (black and white) Bulletin Start August 1 if no ERDA uranit.nn study Start March 1, 1978, if ERDA uranium study Contract for flat fee - 60% from county •••••••••••••• $ 24,000 )< Gs-C!J~C-/j' ~ )( -· /-J t:Cl rT,; >-J c; .,, /~ 6DO ;,, Cdjvz To_; 5;0CJO ;Jl(d-, p F J' cL..,.-'.=. 5 ~ (;Yoo -:? / rtZ,, ✓ J /; ✓ (-; -7so y/- ) <",,,..., •..f10 -0, 4 / 9 CJO 77.o, v _, /-O,.tz: T ;,s ... ~ /.J; L:>Vt 7e.,, u 7o JD";, z 8 3 fl? ,. ,. 2- x: / z. ,c /~ ~ , ' Q ,,,-1 ;;;;-~ / ,,...,,c"? )('. 5 y / 2- )C / ,3. ~ /L~/-'.,'/~5 /4 G'~?--8~·-r - 4 -c,-r 5°' Cr?n-c;;,.>c - ~"'--,s ;' /./'I.,.,,, ✓ ~ "'1L /JJSPc,s,-,s Cc ~&-rs/--. i-v~ ,,'-( qco <- oc,-r- •;,; LJ «: ~,e,o,/ - 7£/ / - - ✓, ~,.G ~ t' )OO -/3Ch/ . • . C),,..J t:,..._,?. ~s "7? .)(/ -0.,...-e:. ~~r. T>m1,~ --<--. ~$r ', 1 ,·? J y ~ /tf. tr--0 ro.. A Jz.&.o If/. IJO '1.i,,,,{ • /tJ.oo /'J.-6-C)O 3, Cf I 00 tJ(tt':ll' 5! 00 ,, .:2,..S~ .56',oo ·' .5t' ro ')..&,/, 00 ,, ~)-1, (co ,. -

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the Re-Opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the re-opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside.... Be Safe! 2 LAWRENCE A. CHITWOOD Go To Special Places 3 EXHIBIT HALL Lava Lands Visitor Center 4-5 DEDICATED MAY 30, 2009 Experience Today 6 For a Better Tomorrow 7 The Exhibit Hall at Lava Lands Visitor Center is dedicated in memory of Explore Newberry Volcano 8-9 Larry Chitwood with deep gratitude for his significant contributions enlightening many students of the landscape now and in the future. Forest Restoration 10 Discover the Natural World 11-13 Lawrence A. Chitwood Discovery in the Kids Corner 14 (August 4, 1942 - January 4, 2008) Take the Road Less Traveled 15 Larry was a geologist for the Deschutes National Forest from 1972 until his Get High on Nature 16 retirement in June 2007. Larry was deeply involved in the creation of Newberry National Volcanic Monument and with the exhibits dedicated in 2009 at Lava Lands What's Your Interest? Visitor Center. He was well known throughout the The Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests are a recre- geologic and scientific communities for his enthusiastic support for those wishing ation haven. There are 2.5 million acres of forest including to learn more about Central Oregon. seven wilderness areas comprising 200,000 acres, six rivers, Larry was a gifted storyteller and an ever- 157 lakes and reservoirs, approximately 1,600 miles of trails, flowing source of knowledge. Lava Lands Visitor Center and the unique landscape of Newberry National Volcanic Monument. Explore snow- capped mountains or splash through whitewater rapids; there is something for everyone. -

First Woman to Climb All Three Sisters in One Day Geologist Ewart Baldwin Breaks New Ground, Turns 90

VOLUME 65 MAY 2005 NUMBER 5 Inside This Issue M. "Doris" Jones (1911-2005) Membership Changes 2 Committee News 2 First Woman to Climb Potlucks 3 All Three Sisters in One Day Board Notes 4 Fundraising Focus 7 M. “DORIS” (SIMS) JONES – an Obsidian who was Book Review 10 the first woman ever to climb all Three Sisters in one Raingear Care 11 day -- died in a retirement home in La Pine, OR, on April 8 of age-related natural causes. She was 93. Trip Reports 13-16 There will be a private scattering of ashes by the Upcoming Events 17-19 family at a later date. Climb Schedule 18 Born Margaret Doris on Nov. 30, 1911, to Harry Calendar into June 19 and Hazel (Austin) Osborn in Watertown, SD, she Features by Members grew up in Eugene and graduated from Eugene High Monday Morning Regulars 5 School in 1930. Doris worked as a school secretary Celebrating V-E, V-J Day 8 from 1948 to 1984, retiring to Bend at that time. In Swop ‘til You Drop 9 1960, she married Frank Jones in Yachats. Survivors include her son Jim (Ann) Sims of Springfield; a Conquering Challenges 12 sister, Blanche Bross of Bend; and two grandchildren. Janet’s Trip Sampler 17 DORIS, "PRINCESS WHITE DOVE," completed Dates to Remember 137 Obsidian trips, including 20 climbs. She also enjoyed gardening, sailing and skiing. Her amazing Three Sisters feat on Labor Day weekend in 1949 was May 20 Potluck Continued on Page 8 May 25 CPR Class June 1 Board Meeting June 4 National Trails Day Geologist Ewart Baldwin June 8 Dining at the Dump June 26 Challenge Course Breaks New Ground, Turns 90 Detailed trip schedules at: OBSIDIANS ARE INVITED to an open house celebrating Ewart Baldwin’s 90th www.obsidians.org or birthday at First United Methodist Church (14th & Olive) from 2 to 5 p.m. -

Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update

Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update Updated June 30, 2017 July Fourth Report! Summer Trail Highlights Summer season high use at recreation sites and trails. Fire season in effect. Possessing or discharging of fireworks prohibited on National Forest Lands. Summer trails below 5,800’ elevation are mostly snow free and accessible. Trail clearing (mostly volunteers) in progress on lower/mid elevation trails. Snow lines are rising to 6,000-7-,200 ft. Please avoid using muddy trails. 60-70% of Wilderness trails are blocked by snow! Wilderness permits required. Biking prohibited in Wilderness! Trails near snow lines (approx.6,000-7,000’) are Be aware of weekday (M-F) trail, road likely muddy. Please avoid using muddy trails as and area closures for logging early season use causes erosion and tread damage. operations, south and west of Cascade Higher elevation trails under patchy, sectional to Lks Welcome Station. near solid snow. 70% of PCT under snow. May 15-Sept 15, dog leash requirement in effect on Deschutes River Trails. Northwest Forest Passes required at various trailheads and day use sites. Cascade Lakes Welcome Station and Lava Lands are open 7 days/wk. NW Forest Passes available. Hwy 46 open but June 19-October 31 bridge related construction at Fall Creek and Goose Creek (Sparks Lk area) will have delays. Cultus Lk and Soda Creek campgrounds are closed until further notice. Go prepared with your Ten Essential Trail clearing in progress on snow free trails with Systems. approx. 50-60% of trails are cleared of down trees. Have a safe summer trails season! GENERAL SUMMER TRAIL CONDITIONS AS OF JUNE 30, 2017: Most Deschutes National Forest non-Wilderness summer trails below 6,000’ elevation are snow free and accessible. -

CHAPTER 14 Obsidian Use in the Willamette Valley and Adjacent Western Cascades of Oregon

CHAPTER 14 Obsidian Use in the Willamette Valley and Adjacent Western Cascades of Oregon Paul W. Baxter and Thomas J. Connolly University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History ([email protected]; [email protected]) Craig E. Skinner Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory ([email protected]) Introduction Interaction spheres recognized throughout the materials…not locally available or only in small Plateau (Hayden and Schulting 1997) and Pacific amounts” (Ames and Maschner 1999:180). On the Northwest Coast (Ames and Maschner 1999; Northwest Coast, one such material is obsidian, Carlson 1994; Galm 1994; Hughes and Connolly which is visually distinctive, easily redistributed, 1999) have been seen as critical in the evolution of and could be used to create more prestige goods for the complex Northwest Coast cultural expression the household’s elites. (Ames 1994:213). Tracking such exchange Because of its trackability, obsidian archaeologically is complicated to the extent that it characterization studies have been integral to involved perishable or consumable goods that have defining interaction spheres extending well into left no trace. But commodities such as obsidian, prehistory (Ames 1994:223). The issue we explore which is both commonly present in archaeological here is the extent to which people of the Willamette contexts in the region and easily traceable to Valley participated in the regional exchange source, provide an important tool in mapping long- networks. The large site-to-site variations seen in distance economic links. the frequencies of Inman Creek and Obsidian Cliffs Previous obsidian characterization studies have obsidians, especially in the lower Willamette speculated that the distribution of obsidian in Valley, imply their distribution as commodities, western Oregon was due to direct procurement and rather than natural deposition. -

Metolius River Subbasin Fish Management Plan

METOLIUS RIVER SUBBASIN FISH MANAGEMENT PLAN UPPER DESCHUTES FISH DISTRICT December 1996 Principal Authors: Ted Fies Brenda Lewis Mark Manion Steve Marx ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The principal authors wish to acknowledge the help, encouragement, comments, and edits contributed by a large number of people including the Technical and Public Advisory Committees, ODFW Fish Division and Habitat Conservation Division staffs, Central Region staffs, other basin planners, district biologists, and staff from other agencies helped answer questions throughout the development of the plan. We especially want to thank members of the public who contributed excellent comments and management direction. We would also like to thank our families and friends who supported us during the five years of completing this task. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iii Map of the Metolius River Subbasin 1 Introduction 2 METOLIUS RIVER AND TRIBUTARIES INCLUDING LAKE CREEK 4 Current Land Classification and Management 4 Access 5 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 6 Fish Resources 11 Fish Stocking History 17 Angling Regulations 19 Fishery 20 Fish Management 21 Management Issues 29 Management Direction 30 SUTTLE AND BLUE LAKES SUBBASIN 41 Suttle and Blue Lakes, and Link Creek 41 Location and Ownership 41 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 42 Fish Stocking History 45 Angling Regulations 46 Fish Management 48 Management Issues 51 Management Direction 52 METOLIUS SUBBASIN HIGH LAKES 57 Overview, Location and Ownership 57 Access 57 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 57 Fish Management 58 Management Issues 61 Management Direction 61 APPENDICES 67 Appendix A: References 67 Appendix B: Glossary 71 Appendix C: Oregon Administrative Rules 77 ii FOREWORD The Fish Management Policy of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) requires that management plans be prepared for each basin or management unit. -

High Desert Region Around Bend, Oregon by Lee Foster

High Desert Region Around Bend, Oregon by Lee Foster Beauty of nature in an alpine setting and diverse outdoor sports attract visitors to the Bend region of Central Oregon. Perusing natural beauty is the most universal pleasure here. Snow-capped mountains, pristine lakes, white-water rivers, and pine forests abound. At any time, the wilderness scenery is striking, with one of the dominant peaks, Mt. Bachelor, Broken Top, and the Sisters, usually present on your horizon. The main natural imprint on the land is a black volcanic presence. For the geology enthusiast, the Lava Lands Visitor Center explains the historic volcanic flows that form a stark legacy. Lava Butte is a 500-foot-high cinder cone, a silent reminder of past volcanic upheavals. A Rockhound Pow-Wow gathers amateur geologists here each July. Since opening in 1982, the High Desert Museum, south of Bend, has emerged as the most important nature interpretive effort in the state. (The High Desert Museum at Bend parallels Tucson’s Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum.) The raptor exhibit alone is worth the visit, putting you as close as you may ever get to a great horned owl, a red-tailed hawk, and an American kestrel. Foremost among the outdoor sports here is skiing at Mt. Bachelor. An extremely long ski season, both for alpine and nordic skiing, lasts into summer. The high- elevation chair lift to the top of Bachelor is popular also with non-skiers who seek an inspiring view of the region. In summer, hikers and campers depart from Bend for the nearby wilderness areas. -

2021.06.11 BBR Resort Map Ktk.Indd

Fire Dept.non–emergency: 541-693-6911 | 911 | 541-693-6911 Dept.non–emergency: Fire . 13511 Hawks Beard, near Bishop’s Cap Cap Bishop’s near Beard, Hawks 13511 ROCK CLIMBING helicopters transport from the Sports Field. Field. Sports the from transport helicopters EXPLORE THE make up the Ranch. Ranch. the up make First Ascent Climbing o¡ers specialized climbing and has a fully-equipped fi rst aid room. Medical Medical room. aid rst fi fully-equipped a has and ums and various cabin clusters. About 1,200 homesites homesites 1,200 About clusters. cabin various and ums ADVENTURES services at Smith Rock State Park for all abilities. The BBR Fire Dept. is sta¡ ed with paramedics 24/7 24/7 paramedics with ed sta¡ is Dept. Fire BBR The Meadow (south). There also are three sets of condomini- of sets three are also There (south). Meadow BBR recommends helmets for all riders. all for helmets recommends BBR 1-866-climb11 | GoClimbing.com Home, South Meadow and Rock Ridge (center), and Glaze Glaze and (center), Ridge Rock and Meadow South Home, FIRST AID AID FIRST BACKYARD WITH OUTFITTERS when operating a bicycle, Razor, or inline skates. skates. inline or Razor, bicycle, a operating when into sections: Golf Home (NW), East Meadow (NE), Spring Spring (NE), Meadow East (NW), Home Golf sections: into BLACK BUTTE LOOKOUT • Anyone under 16 needs to wear a HELMET HELMET a wear to needs 16 under Anyone • for such a large residential resort. The Ranch is divided divided is Ranch The resort. residential large a such for FLY FISHING Police non–emergency: 541-693-6911 | 911 | 541-693-6911 non–emergency: Police Ranch Homeowners’ Association, a unique arrangement arrangement unique a Association, Homeowners’ Ranch Hike BBR’s namesake in this 3.6 mile, 1,556 foot climb. -

Red Butte Cinder Pit Expansion Project Environmental Assessment

Red Butte Cinder Pit Expansion Project United States Environmental Assessment Bend-Fort Rock Ranger District Department of Agriculture Deschutes National Forest Deschutes County, Oregon Forest Service February 2015 Township 18 South, Range 11 East, Section 28 Willamette Meridian For More Information Contact: Beth Peer, Environmental Coordinator 63095 Deschutes Market Road Bend, OR 97701 Phone: 541-383-4769 [email protected] Red Butte Pit Expansion EA The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Red Butte Pit Expansion EA TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... 1 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... -

View Site Details

Curtis Ct Eugene Barclay Dr 126 To Hoodoo Ski Area To Camp Polk Area/ Sisters, Oregon Suttle Lake 20 Salem Sheriff’s Indian Ford Springs Black Butte Ranch Barclay Dr Office Post Office Aylor Ct Squaw Creek Canyon 22 Corvallis Camp Sherman Yapoah Crater Dr Metolious Arrow Leaf Trail Tollgate Areas Tam Rim Dr Sisters Park Dr Mckinney Butte Rd Park Pl Larch St Sisters Park Ct Parkside Ln Parkside Blackbutte Ave Black Butte Ave Maple St Locust Ln High Maple Ln School Industrial Park Aspenwood Ave Sisters Area Tamarack St Songbird St Collier Glacier Dr Chamber of Commerce and Information Center Sentry Fir StFir Trinity Way Trinity Adams Ave Green Ridge Ave 126 Forest Ranch Ave Wheeler Loop Service Rope Pl Loop Locust St Pine St Elm St Middle Ash St Main Ave 20 Spruce St Canter Ct School Sisters Cedar St HoodAve Ranger Library Brooks Camp Rd Station Cascade Ave/Hwy 20 Cowboy St Rope St Perit Huntington Rd 242 Cascade Ave Dark Horse Ln City Hall To McKenzie Pass Scenic Route Timber Creek Alley (Closed in Winter at Milepost 84) Creekside Dr Dee Wright Observatory Oak St Hood Ave Timber Pine Dr Crossroads Subdivision Elementary School Cold Springs Campground Creek View Dr (Milepost 88) Washington Ave Timber Creek Dr Larch St Cedar St Fire Village Whychus Creek Hall Green Park Public Restrooms Jefferson Ave Jefferson Ave West Village Alley Creekside Ct Playground/Park Spruce St School StFir St Helens Ave Creekside Dr Information Locations 126 Population: 1,490 Elm St To Redmond Overnight Camping Sisters Elevation: 3,182’ Sisters City Park Dr Aspen -

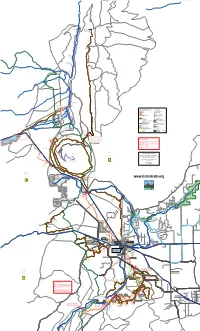

Sisters Area Trails System

d a o r h g u o r p e e t s : N O I T U A C F S 1 4 9 0 40 11 FS !Z Prairie Farm : : Guard Station 0 G 1490-900 27 1 0 T S G F 9 H Lower Bridge 4 ! 1 Green Ridge Trail S F ends at junction with spur road FS 1490900 ")12 0 4 1 1 S F E G D I R FS 1154 1140-600 !Z F Green Ridge S 14 1 ")12 0 ") 1 7 Lookout 5 2 0 1 S F Wizard Falls Fish Hatchery !Z N E E R G West Metolius River Trail Metoliu s Windigo Trail 1 420 -40 Lower ek 0 Canyon Cre Canyon Creek Campground !9T !H k ee Cr ck Ja 0 2 ")12 4 1 S F F S 1 1 5 0 F S 1 2 3 0 FS 1425 ek re t C Firs ")11 ")12 ")14 F S 1 1 r 2 e 0 v i / R A l s l i n u i g l h o a t m e Metolius River Trail C M u l t i o (hiking only) a f f r R T d Lake Creek Trail e Camp g d Continues 4.3 miles Sherman i to Suttle Lake R 17 2 Store n 1 e S F e· e r G Mountain bike/pedestrian trail e· Information T !H Easy !G Bike store/services Moderate !Ê Horse camp T 16 Difficult !H Trailhead, Multi-Use 12 FS T d H R Old PRT Trail (easy) ! Trailhead, Hiking Only n a m !9 Campground r e ) h S es Horse trail !Z Place of interest i l p m m (4.3 a C Proposed trail Sisters Ranger District k Trail !@ ree k e C ake Cree â â â â Route from Village Green to PRT Shared road (gravel-cinder) Lak North Fork L Metolius Windigo Trail Road reek Middle Fork Lake C (Oregon State Scenic Trail, Unimproved road (not all primarily a horse trail) roads are shown on map) Hiking only Highway Head of the Whychus Draw Trail Creek Scenic bikeway Fork Lake ")11 th G Sou Metolius Trail Whychus Overlook Loop Trail (hiking only) City of Sisters !( 1 Junction number Deschutes Land Trust preserve ")14 Upper k ")12 Viewpoint (Hiking Only) Butte T G T Loop H !H ! FS 1430 Connector " Lodge T !H Upper Butte Loop Parking for the Green Ridge Trail is available at the trail crossing on FS 1120 / F S Allingham Cutoff Rd.