CHAPTER 14 Obsidian Use in the Willamette Valley and Adjacent Western Cascades of Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jefferson County General Reports

JEFFERSON COUNT¥ ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY STUDY Geologist (125 days@ $125/day) • $ 15,600 * Editing (65 days@ $77/day) • 5,000 * Cartography. 4,000 * Supplies. • 750 * Printing. • 4,900 Travel and per diem Per diem - $27.50 x 60 days •••••••••• • $1,650 Travel to job - 566 (mi. round trip) x 12 x 14¢. 948 Travel on job - 100 x 60 x 14¢ • • •••• 840 3,438 * Overhead on* items above - $28,788 x 20%. 5,757 TOTAL. • • • $ 39,445 Maps: (1) Geology - 4 or 5 color (1 inch= 3 miles) (2) Mineral deposits (combine with geology?) (3) Urban - 7~' - 1:24,000 (black and white) Bulletin Start August 1 if no ERDA uranit.nn study Start March 1, 1978, if ERDA uranium study Contract for flat fee - 60% from county •••••••••••••• $ 24,000 )< Gs-C!J~C-/j' ~ )( -· /-J t:Cl rT,; >-J c; .,, /~ 6DO ;,, Cdjvz To_; 5;0CJO ;Jl(d-, p F J' cL..,.-'.=. 5 ~ (;Yoo -:? / rtZ,, ✓ J /; ✓ (-; -7so y/- ) <",,,..., •..f10 -0, 4 / 9 CJO 77.o, v _, /-O,.tz: T ;,s ... ~ /.J; L:>Vt 7e.,, u 7o JD";, z 8 3 fl? ,. ,. 2- x: / z. ,c /~ ~ , ' Q ,,,-1 ;;;;-~ / ,,...,,c"? )('. 5 y / 2- )C / ,3. ~ /L~/-'.,'/~5 /4 G'~?--8~·-r - 4 -c,-r 5°' Cr?n-c;;,.>c - ~"'--,s ;' /./'I.,.,,, ✓ ~ "'1L /JJSPc,s,-,s Cc ~&-rs/--. i-v~ ,,'-( qco <- oc,-r- •;,; LJ «: ~,e,o,/ - 7£/ / - - ✓, ~,.G ~ t' )OO -/3Ch/ . • . C),,..J t:,..._,?. ~s "7? .)(/ -0.,...-e:. ~~r. T>m1,~ --<--. ~$r ', 1 ,·? J y ~ /tf. tr--0 ro.. A Jz.&.o If/. IJO '1.i,,,,{ • /tJ.oo /'J.-6-C)O 3, Cf I 00 tJ(tt':ll' 5! 00 ,, .:2,..S~ .56',oo ·' .5t' ro ')..&,/, 00 ,, ~)-1, (co ,. -

Metolius River Subbasin Fish Management Plan

METOLIUS RIVER SUBBASIN FISH MANAGEMENT PLAN UPPER DESCHUTES FISH DISTRICT December 1996 Principal Authors: Ted Fies Brenda Lewis Mark Manion Steve Marx ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The principal authors wish to acknowledge the help, encouragement, comments, and edits contributed by a large number of people including the Technical and Public Advisory Committees, ODFW Fish Division and Habitat Conservation Division staffs, Central Region staffs, other basin planners, district biologists, and staff from other agencies helped answer questions throughout the development of the plan. We especially want to thank members of the public who contributed excellent comments and management direction. We would also like to thank our families and friends who supported us during the five years of completing this task. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iii Map of the Metolius River Subbasin 1 Introduction 2 METOLIUS RIVER AND TRIBUTARIES INCLUDING LAKE CREEK 4 Current Land Classification and Management 4 Access 5 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 6 Fish Resources 11 Fish Stocking History 17 Angling Regulations 19 Fishery 20 Fish Management 21 Management Issues 29 Management Direction 30 SUTTLE AND BLUE LAKES SUBBASIN 41 Suttle and Blue Lakes, and Link Creek 41 Location and Ownership 41 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 42 Fish Stocking History 45 Angling Regulations 46 Fish Management 48 Management Issues 51 Management Direction 52 METOLIUS SUBBASIN HIGH LAKES 57 Overview, Location and Ownership 57 Access 57 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 57 Fish Management 58 Management Issues 61 Management Direction 61 APPENDICES 67 Appendix A: References 67 Appendix B: Glossary 71 Appendix C: Oregon Administrative Rules 77 ii FOREWORD The Fish Management Policy of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) requires that management plans be prepared for each basin or management unit. -

2021.06.11 BBR Resort Map Ktk.Indd

Fire Dept.non–emergency: 541-693-6911 | 911 | 541-693-6911 Dept.non–emergency: Fire . 13511 Hawks Beard, near Bishop’s Cap Cap Bishop’s near Beard, Hawks 13511 ROCK CLIMBING helicopters transport from the Sports Field. Field. Sports the from transport helicopters EXPLORE THE make up the Ranch. Ranch. the up make First Ascent Climbing o¡ers specialized climbing and has a fully-equipped fi rst aid room. Medical Medical room. aid rst fi fully-equipped a has and ums and various cabin clusters. About 1,200 homesites homesites 1,200 About clusters. cabin various and ums ADVENTURES services at Smith Rock State Park for all abilities. The BBR Fire Dept. is sta¡ ed with paramedics 24/7 24/7 paramedics with ed sta¡ is Dept. Fire BBR The Meadow (south). There also are three sets of condomini- of sets three are also There (south). Meadow BBR recommends helmets for all riders. all for helmets recommends BBR 1-866-climb11 | GoClimbing.com Home, South Meadow and Rock Ridge (center), and Glaze Glaze and (center), Ridge Rock and Meadow South Home, FIRST AID AID FIRST BACKYARD WITH OUTFITTERS when operating a bicycle, Razor, or inline skates. skates. inline or Razor, bicycle, a operating when into sections: Golf Home (NW), East Meadow (NE), Spring Spring (NE), Meadow East (NW), Home Golf sections: into BLACK BUTTE LOOKOUT • Anyone under 16 needs to wear a HELMET HELMET a wear to needs 16 under Anyone • for such a large residential resort. The Ranch is divided divided is Ranch The resort. residential large a such for FLY FISHING Police non–emergency: 541-693-6911 | 911 | 541-693-6911 non–emergency: Police Ranch Homeowners’ Association, a unique arrangement arrangement unique a Association, Homeowners’ Ranch Hike BBR’s namesake in this 3.6 mile, 1,556 foot climb. -

View Site Details

Curtis Ct Eugene Barclay Dr 126 To Hoodoo Ski Area To Camp Polk Area/ Sisters, Oregon Suttle Lake 20 Salem Sheriff’s Indian Ford Springs Black Butte Ranch Barclay Dr Office Post Office Aylor Ct Squaw Creek Canyon 22 Corvallis Camp Sherman Yapoah Crater Dr Metolious Arrow Leaf Trail Tollgate Areas Tam Rim Dr Sisters Park Dr Mckinney Butte Rd Park Pl Larch St Sisters Park Ct Parkside Ln Parkside Blackbutte Ave Black Butte Ave Maple St Locust Ln High Maple Ln School Industrial Park Aspenwood Ave Sisters Area Tamarack St Songbird St Collier Glacier Dr Chamber of Commerce and Information Center Sentry Fir StFir Trinity Way Trinity Adams Ave Green Ridge Ave 126 Forest Ranch Ave Wheeler Loop Service Rope Pl Loop Locust St Pine St Elm St Middle Ash St Main Ave 20 Spruce St Canter Ct School Sisters Cedar St HoodAve Ranger Library Brooks Camp Rd Station Cascade Ave/Hwy 20 Cowboy St Rope St Perit Huntington Rd 242 Cascade Ave Dark Horse Ln City Hall To McKenzie Pass Scenic Route Timber Creek Alley (Closed in Winter at Milepost 84) Creekside Dr Dee Wright Observatory Oak St Hood Ave Timber Pine Dr Crossroads Subdivision Elementary School Cold Springs Campground Creek View Dr (Milepost 88) Washington Ave Timber Creek Dr Larch St Cedar St Fire Village Whychus Creek Hall Green Park Public Restrooms Jefferson Ave Jefferson Ave West Village Alley Creekside Ct Playground/Park Spruce St School StFir St Helens Ave Creekside Dr Information Locations 126 Population: 1,490 Elm St To Redmond Overnight Camping Sisters Elevation: 3,182’ Sisters City Park Dr Aspen -

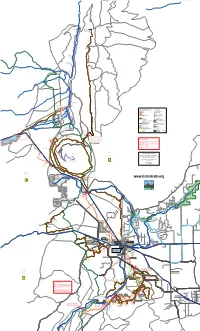

Sisters Area Trails System

d a o r h g u o r p e e t s : N O I T U A C F S 1 4 9 0 40 11 FS !Z Prairie Farm : : Guard Station 0 G 1490-900 27 1 0 T S G F 9 H Lower Bridge 4 ! 1 Green Ridge Trail S F ends at junction with spur road FS 1490900 ")12 0 4 1 1 S F E G D I R FS 1154 1140-600 !Z F Green Ridge S 14 1 ")12 0 ") 1 7 Lookout 5 2 0 1 S F Wizard Falls Fish Hatchery !Z N E E R G West Metolius River Trail Metoliu s Windigo Trail 1 420 -40 Lower ek 0 Canyon Cre Canyon Creek Campground !9T !H k ee Cr ck Ja 0 2 ")12 4 1 S F F S 1 1 5 0 F S 1 2 3 0 FS 1425 ek re t C Firs ")11 ")12 ")14 F S 1 1 r 2 e 0 v i / R A l s l i n u i g l h o a t m e Metolius River Trail C M u l t i o (hiking only) a f f r R T d Lake Creek Trail e Camp g d Continues 4.3 miles Sherman i to Suttle Lake R 17 2 Store n 1 e S F e· e r G Mountain bike/pedestrian trail e· Information T !H Easy !G Bike store/services Moderate !Ê Horse camp T 16 Difficult !H Trailhead, Multi-Use 12 FS T d H R Old PRT Trail (easy) ! Trailhead, Hiking Only n a m !9 Campground r e ) h S es Horse trail !Z Place of interest i l p m m (4.3 a C Proposed trail Sisters Ranger District k Trail !@ ree k e C ake Cree â â â â Route from Village Green to PRT Shared road (gravel-cinder) Lak North Fork L Metolius Windigo Trail Road reek Middle Fork Lake C (Oregon State Scenic Trail, Unimproved road (not all primarily a horse trail) roads are shown on map) Hiking only Highway Head of the Whychus Draw Trail Creek Scenic bikeway Fork Lake ")11 th G Sou Metolius Trail Whychus Overlook Loop Trail (hiking only) City of Sisters !( 1 Junction number Deschutes Land Trust preserve ")14 Upper k ")12 Viewpoint (Hiking Only) Butte T G T Loop H !H ! FS 1430 Connector " Lodge T !H Upper Butte Loop Parking for the Green Ridge Trail is available at the trail crossing on FS 1120 / F S Allingham Cutoff Rd. -

Bulletin of the Native Plant Society of Oregon

View this email in your browser Bulletin of the Native Plant Society of Oregon Dedicated to the enjoyment, conservation, and study of Oregon's native plants and habitats August/September 2018 Volume 51, No. 7 Welcome to the e‑Bulletin! While we are looking for a permanent editor, the Bulletin will be published as an e‑newsletter. Welcome to the first edition! Please note that when the new NPSO website is functional, the Bulletin will be adding new features that will increase the functionality of this e‑newsletter. Also, if you prefer to read a hard copy, you can click on the link at the top of this email that says "view this email in your browser," and then print this e‑ newsletter as a PDF. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected]. Table of Contents: ‑ 2018 Annual Meeting Recap ‑ 2018 IAE/NPSO Intern Report ‑ State/Chapter Notes ‑ Kalmiopsis Authors Wanted! ‑ OregonFlora 2018 Annual Meeting Recap: By Susan Saul Brown's Peony (Paeonia brownii) on Lookout Mountain, June 2, 2018. One‑hundred twenty registrants attended the NPSO Annual Meeting held on June 1‑3, 2018, in Prineville, Oregon. Joint hosts were the Portland Chapter and the High Desert Chapter. The host chapters chose Brown’s peony (Paeonia brownii) as the botanical mascot for the meeting. It is a common, even abundant, species in appropriate habitats in the Ochoco Mountains. Brown’s peony, also known as western peony, is a low to medium height, herbaceous perennial flowering plant in the family Paeoniaceae. It grows in open, dry ponderosa pine forests, in sagebrush, and in aspen stands at higher elevations where winters are long and cold and the growing season is short. -

2003 Annual Report ● Page 1

Stayton Fire District 2003 Annual Report ● Page 1 2003 "Volunteer Service With ANNUAL REPORT Pride" Serving the Communities of Elkhorn, Marion, Mehama, and Stayton and equipment to help minimize the dam- In April we grieved with the passing of age of the destructive fire. All crews re- From the one of our Support members and a com- turned safely with many new experiences munity icon, Fussy Fuson. Fussy will and valuable training. In December the Chief’s Desk long be remembered for his relentless Volunteers concluded several years of commitment to the community. In the work with the formal creation of a single 003 presented a wide range of month of June, Tony Becker, a volunteer District-wide Volunteer Association challenges to the volunteers and firefighter with the District, was involved called Stayton Volunteer Protection Com- staff of Stayton Fire District. In in a very serious motor vehicle accident pany #1. With a renewed spirit of coop- addition to responding to a record on Hwy. 22. At the time of the accident eration between stations and the forma- 2number of calls for service, the District Tony’s wife Yvonne was pregnant with tion of the Volunteer Association the Dis- also experienced a number of unique their second child. Tony received very trict is experiencing an increased level of events. serious head injuries and remained in a unity and camaraderie. coma for three months and to date is still The District started the year, like many battling day-to-day towards his recovery. On the operations side of the District, families, with one of our own volunteers We are happy to say that Yvonne gave through input from the Firefighters and serving in the war in Kuwait. -

Task 3. Containment Strategies for Eurasian Watermilfoil Infested Central OR Lakes

Portland State University PDXScholar Center for Lakes and Reservoirs Publications and Presentations Center for Lakes and Reservoirs 2014 OSMB Final Report: Task 3. Containment Strategies for Eurasian Watermilfoil Infested Central OR Lakes Vanessa Morgan Portland State University Mark Sytsma Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/centerforlakes_pub Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Morgan, Vanessa and Sytsma, Mark, "OSMB Final Report: Task 3. Containment Strategies for Eurasian Watermilfoil Infested Central OR Lakes" (2014). Center for Lakes and Reservoirs Publications and Presentations. 33. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/centerforlakes_pub/33 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Lakes and Reservoirs Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Task 3 – 1 OSMB Final Report: Task 3. Containment Strategies for Eurasian Watermilfoil Infested Central OR Lakes Final Report submitted by: Vanessa Morgan and Mark Sytsma for Oregon State Marine Board funded by Aquatic Invasive Species grant to the Aquatic Bioinvasions Research and Policy Institute Portland State University Task 3 – 2 Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. -

Winter Trail Guide

SISTERS AREA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE SISTERS WINTERAREA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE TRAIL GUIDE Sisters Area Chamber of Commerce www.thesisterscountry.com Special thanks to EST SERVI FOR CE D E E P U S R A U R TMENT OF AGRICU L T DAY USE OF USFS TRAILS Always use good judgement when using or traveling over trails and roads. Some are not maintained and may be hazardous. Weather and other conditions can change without notice, so carry clothing for rain and cold temperatures. Always carry adequate water for all hikes and never drink trailside water from lakes and streams unless marked “potable” by the Forest Service. Food, matches, first-aid kit, flashlight, compass and maps are also essential. Deschutes and Willamette National Forest Maps, the McKenzie River National Recreation Trail Map , and the Three Sisters, Mt. Washington, and Mt. Jefferson Wilderness maps are available at Forest Service Stations. Mosquito repellent should also be carried along in late spring and summer months. As a safety precaution, always let someone know where you are going and when you expect to return. Dogs should be on a leash or controlled by voice command. Be sure to have appropriate parking and trail permits for specific destinations. The Sisters Area Chamber of Commerce and its members are not responsible for losses or injuries incurred when utilizing this information. Wilderness Areas and US Forest Service Land Uses Wilderness Areas have a delicate state of natural balance. Careless acts by people can upset this balance, resulting in destruction of the wilderness environment. The following practices will help preserve the wilderness for everyone’s enjoyment. -

EXPERIENCE OREGON BOATING Safety, Regulations and How-To’S for Fun Boating

EXPERIENCE OREGON BOATING Safety, Regulations and How-To’s for Fun Boating POWER PADDLE SAIL EXPERIENCE OREGON BOATING Your Oregon State Marine Board Your Marine Board is unique from other state agencies Like most outdoor recreation, boating can be relaxing, and even other states, because we are an agency devoted exhilarating and liberating, with a wealth of places to entirely to recreational boating with dedicated funding explore and activities that provide countless hours of supported by motorboat user fees. Your registration dollars enjoyment. It’s our goal to share these waterways for the help pay for marine law enforcement services with the maximum enjoyment of all boaters. Courtesy and respect county sheriff’s offices and the Oregon State Police, grants are essential ingredients for a great boating experience. for launch ramps and other boating facility improvements, We are here to help you: boating safety education and education outreach materials for various programs within the agency. The aquatic • Discover Oregon’s plentiful and diverse waterways for invasive species prevention permit program that non- every type of boating activity; motorized boaters who operate boats 10’ long and longer • Enjoy your boating in a safe environment with the help go into a dedicated account to help fund border inspection of on-the-water law enforcement; stations, decontamination equipment and inspectors. The • Become educated about boating safety, waterway Marine Board does not receive any general fund or lottery regulations, proper waste disposal, aquatic invasive funds, nor does it receive parking or launch fees from species and stewardship of the environment; facility owners. The Marine Board does not own or operate • Access Oregon’s waterways with modern boat any facilities; instead, relies on partnerships with local and launches, boarding docks, floating restrooms and tribal governments, and state or federal agencies who pump-out and dump stations. -

Sisters Forest Service Property Offering 66.57 Acres | $8,000,000 Memorandum

Sisters Forest Service Property Offering 66.57 Acres | $8,000,000 Memorandum Robert Raimondi, CCIM | Graham Dent, Broker 600 SW Columbia St., Ste. 6100 | Bend, OR 97702 541.383.2444 | www.compasscommercial.com Table of Contents Page Property Overview Location Overview 03 11 Sisters Demographics Regional Map Property Offering 04 Offering Details Parcel Breakdown Regional Overview Building Inventory 14 Sisters, Oregon Profile Central Oregon Profile Zoning Overview 07 Current Zoning Map Notices Zoning Change Options 16 2 Property Sisters Forest Service Property Overview A 66.57-acre land parcel fronting Highway 20 in Downtown Sisters, Oregon. Compass Commercial is proud to present an THE SUBJECT PROPERTY extremely rare development opportunity in downtown Sisters, Oregon. This 66.57-acre parcel This parcel is currently used for administrative and employee has over 2,000 feet of Highway 20 frontage and is residential purposes for the operations of the Sisters the connector between downtown Sisters to the Ranger District of the Deschutes National Forest. The city’s east and the commercial strip to the west. comprehensive plan for this area was revised in 2012 to include a number of options as to how this site could be developed. These revisions allow for a variety of approved zones including SISTERS, OREGON commercial, residential and industrial. Sisters is a city in Deschutes County, Oregon, 136 miles southeast This is a rare opportunity to shape the look, feel and personality of Portland and just 20 miles west of both Bend and Redmond. of a community for generations to come. The population was 1,196 at the 2000 census, but nearly doubled to 2,038 as of the 2010 census. -

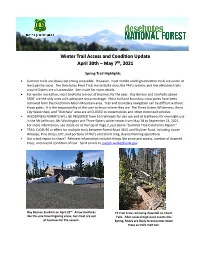

Winter Trail Access and Condition Update April 30Th – May 7Th, 2021

z Winter Trail Access and Condition Update April 30th – May 7th, 2021 Spring Trail Highlights • Summer trails are slowly becoming accessible. However, most middle and high elevation trails are under at least patchy snow. The Deschutes River Trail, Horse Butte area, the Phil’s system, and low elevation trails around Sisters are all accessible. See inside for more details. • For winter recreation, most SnoParks are out of business for the year. Ray Benson and SnoParks above 5500’ are the only ones with adequate snow coverage. Most trail and boundary snow poles have been removed from the Dutchman-Moon Mountain area. Trail and boundary navigation can be difficult without these poles. It is the responsibility of the user to know where they are. The Three Sisters Wilderness, Bend City Watershed, and “Dutchalo” area are all CLOSED to snowmobiles and other motorized vehicles. • WILDERNESS PERMITS WILL BE REQUIRED from 19 trailheads for day use and all trailheads for overnight use in the Mt Jefferson, Mt Washington and Three Sisters wildernesses from May 28 to September 24, 2021. For more information, see inside on at the top of Page 2, just above “Summer Trail Conditions Report.” • TRAIL CLOSURE in effect for multiple trails between Forest Road 4615 and Skyliner Road, including Lower Whoops, Pine Drops, EXT, and portions of Phil’s and Storm King, due to thinning operations. • Got a trail report to share? Relevant information includes things like snow and access, number of downed trees, and overall condition of trail. Send emails to [email protected] rd Ray Benson SnoPark on April 23 .