Chapter 10 (.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Journey Treasures from the Archives

GRAND TOUR ITALIANO: CINEMA TREASURES FROM THE ARCHIVES (c. 1909–12, total screening time: 70 mins.) Curated by Andrea Meneghelli, Cineteca di Bologna This program is presented virtually on wexarts.org Feb 28–Mar 6, 2021, as part of Cinema Revival: A Festival of Film Restoration, organized by the Wexner Center for the Arts. At the beginning of the 20th century, cinema offered production houses in Italy—and elsewhere—the extraordinary possibility of depicting Italy to the world and to the new citizens of the unified state, permitting everyone to go on a low cost, virtual Grand Tour. The production of “real life” Italian cinema during the early 1910s gives us the picture of a modern, industrialized country, which, at the same time, boasts the age-old traditions of its history and the incomparable artistic and natural beauty of its territory. In the ports of Genoa and Naples, while groups of foreign tourists disembark from steamboats, the docks are crowded with millions of emigrants, ready to set sail for Argentina, Canada, the United States...Italy is no longer a country for them. Images were shot throughout Italy, from Sicily to Valle d’Aosta, from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic. The films were made by both Italian and international production houses, because the Bel paese (beautiful country) at once became the destination of choice for cine-camera operators sent out to capture “the Beautiful.” The operators (and their production houses) followed the lessons of the Lumière brothers, framing Italy with wisdom, using a new language written for the moving image, and with true technical know-how: manually colored images, split-screen, fixed cameras, cameras in movement.. -

Beyond Autonomy in Eighteenth-Century and German Aesthetics

10 Goethe’s Exploratory Idealism Mattias Pirholt “One has to always experiment with ideas.” Georg Christoph Lichtenberg “Everything that exists is an analogue to all existing things.” Johann Wolfgang Goethe Johann Wolfgang Goethe made his famous Italian journey in the late 1780s, approaching his forties, and it was nothing short of life-c hanging. Soon after his arrival in Rome on November 1, 1786, he writes to his mother that he would return “as a new man”1; in the retroactive account of the journey in Italienische Reise, he famously describes his entrance into Rome “as my second natal day, a true rebirth.”2 Latter- day crit- ics essentially confirm Goethe’s reflections, describing the journey and its outcome as “Goethe’s aesthetic catharsis” (Dieter Borchmeyer), “the artist’s self-d iscovery” (Theo Buck), and a “Renaissance of Goethe’s po- etic genius” (Jane Brown).3 Following a decade of frustrating unproduc- tivity, the Italian sojourn unleashed previously unseen creative powers which would deeply affect Goethe’s life and work over the decades to come. Borchmeyer argues that Goethe’s “new existence in Weimar bore an essentially different signature than his pre- Italian one.”4 With this, Borchmeyer refers to a particular brand of neoclassicism known as Wei- mar classicism, Weimarer Klassik, which is less an epochal term, seeing as it covers only a little more than a decade, than a reference to what Gerhard Schulz and Sabine Doering matter-o f- factly call “an episode in the creative history of a group of German writers around 1800.”5 Equally important as the aesthetic reorientation, however, was Goethe’s new- found interest in science, which was also a direct conse- quence of his encounter with the Italian nature. -

The Interpretation of Italy During the Last Two Centuries

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 6^60/ 111- DATE DUE 'V rT ^'iinih'^ ,.^i jvT^ifim.mimsmi'^ / PRINTED IN U S A. / CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 082 449 798 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924082449798 THE DECENNIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE DECENNIAL PUBLICATIONS ISSUED IN COMMEMORATION OP THE COMPLETION OP THE PIEST TEX TEARS OP THE UNIVERSITY'S EXISTENCE AUTHORIZED BY THE BOARD OP TRUSTEES ON THE RECOMMENDATION OP THE PRESIDENT AND SENATE EDITED BY A COMMITTEE APPOINTED BY THE SENATE EDWABD CAPP3 STARR WILLARD CUTTING EOLLIN D. SALISBtTKT JAME9 ROWLAND ANGELL "WILLIAM I. THOMAS SHAILER MATHEWS GAEL DARLING BUCK FREDERIC IVES CARPENTER OSKAB BOLZA JDLIBS 3TIBGLITZ JACQUES LOEB THESE VOLXJMBS ARE DEDICATED TO THE MEN AKD WOMEN OP CUB TIME AND COUNTRY WHO BY WISE AND GENEK0U3 GIVING HAVE ENCOUBAGED THE SEARCH AFTBB TBUTH IN ALL DEPARTMENTS OP KNOWLEDGE THE INTERPRETATION OF ITALY THE INTERPRETATION OF ITALY DURING THE LAST TWO CENTURIES A CONTKIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF GOETHE'S "ITALIENISCHE KEISE" CAMILLO voN^LENZE rORMBBLI OF THE DBPAETMENT OF GEKMANIC LANGUAGES AND LITEEATUBES. NOW PEOFBSSOE OF GEKMAN IiITEBATDEE IN BEOTVN UNIVEESITT THE DECENNIAL PUBLICATIONS SECOND SERIES VOLUME XVII CHICAGO THE UNIVBKSITY OP CHICAGO PRESS 1907 'y\ Copyright 19(yt by THE UNIVEESIT¥ OF CHICAGO Published April 1907 ^' / (7 ^SJ^ Composed and Printecl By The University of Chicago Press Chicago, Illinois, U. S. A. ACKNOWLEDGMENT I owe grateful acknowledgment, for valuable assistance in procuring material, to the Libraries of the University of Chicago, of Harvard University, of Cornell University, and of the City of Boston. -

The Essential Goethe

Introduction Reading a French translation of his drama Faust in 1828, Goethe was struck by how “much brighter and more deliberately constructed” it appeared to him than in his original German. He was fascinated by the translation of his writing into other languages, and he was quick to acknowledge the important role of translation in modern culture. Literature, he believed, was becoming less oriented toward the nation. Soon there would be a body of writing— “world literature” was the term he coined for it— that would be international in scope and readership. He would certainly have been delighted to find that his writing is currently enjoying the attention of so many talented translators. English- speaking readers of Faust now have an embarrassment of riches, with modern versions by David Luke, Randall Jarrell, John Williams, and David Constantine. Constantine and Stanley Corngold have recently produced ver- sions of The Sorrows of Young Werther, the sentimental novel of 1774 that made Goethe a European celebrity and prompted Napoleon to award him the Le- gion d’Honneur. Luke and John Whaley have done excellent selections of Goethe’s poetry in English. At the same time the range of Goethe’s writing available in English remains quite narrow, unless the reader is lucky enough to find the twelve volumes of Goethe’s Collected Works published jointly by Princeton University Press and Suhrkamp Verlag in the 1980s. The Princeton edition was an ambitious undertaking. Under the general editorship of three Goethe scholars, Victor Lange, Eric Blackall, and Cyrus Hamlyn, it brought together versions by over twenty translators covering a wide range of Goethe’s writings: poetry, plays, novels and shorter prose fiction, an autobiography, and essays on the arts, philosophy, and science. -

Goethe the Musician and His Influence on German Song Transcript

Goethe the Musician and his influence on German Song Transcript Date: Friday, 20 June 2008 - 12:00AM GOETHE THE MUSICIAN AND HIS INFLUENCE ON GERMAN SONG Professor Richard Stokes It has become fashionable to label Goethe unmusical. In April 1816 he failed to acknowledge Schubert's gift of 16 settings of his own poems which included such masterpieces as 'Gretchen am Spinnrade', 'Meeresstille', 'Der Fischer' and 'Erlkönig'. He did not warm to Beethoven when they met in 1812. He preferred Zelter and Reichardt to composers that posterity has deemed greater. And he wrote in his autobiography,Dichtung und Wahrheit : 'Das Auge war vor allen anderen das Organ, womit ich die Welt erfasste' ('It was through the visual, above all other senses, that I comprehended the world') - a statement which seems to be confirmed by his indefatigable study of natural phenomena and his delight in art and architecture, in seeing. Lynceus's line at the end of Faust , 'Zum Sehen geboren, zum Schauen bestellt' ('I was born for seeing, employed to watch') has an unmistakably autobiographical ring. Goethe was, above all a visual being, an Augenmensch,. He was also, from his earliest days in Frankfurt, intensely musical. His father brought a Giraffe, an upright Hammerklavier, for 60 Gulden in 1769, played the lute and flute and occasionally made music with friends - there is an amusing passage in Dichtung und Wahrheit which describes his father playing the lute,"die er länger stimmte, als er darauf spielte" ("which he spent longer tuning than playing")! His mother, who was more artistic, played the piano and sang German and Italian arias with great enthusiasm. -

Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe: Literature, Philosophy, and Science

Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe: Literature, Philosophy, and Science HIST 25304/ 35304, CHSS 31202 PHIL 20610/30610, GRMN 25304/ 35304, HIPS 26701 Instructor: Robert J. Richards Assistants: Sarah Panzer, Jake Smith I. The following texts for the course may be found at the Seminary Co-operative Bookstore: A. Primary Texts: Goethe, Sorrows of Young Werther (Modern Library, trans. Burton Pike) Goethe, Italian Journey (Viking Penguin, trans. Auden, W.H. and Meyer, Elizabeth) Goethe, Faust, Part One (Oxford U.P.–World’s Classics; trans. David Luke) Goethe, Selected Verse (Penguin) B. German editions for those who would like to try their hand; the following are also in the Seminary Co-Operative Bookstore: Goethe, Die Leiden des jungen Werther (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag) Goethe, Italienische Reise (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag) Goethe, Faust, Erster und zweiter Teil (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag) C. Packets of Photocopies: Goethe: Primary Readings (for sale in Social Sciences 205) Goethe: Secondary Readings (for sale in Social Sciences 205) D. Recommended text: Robert J. Richards, The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe (University of Chicago Press). II. Requirements: A. You will be responsible for preparing texts assigned for discussion, and it is imperative that you do so. You should also take seriously those items under recommended reading. B. In the first half of the class, the instructor will provide short lectures to introduce 1 topics drawn from the readings. In the second half of each class, discussion will be initiated from very short papers that all students must have produced for that class. These papers—no longer than one-two pages—should state some problem, question, or central aspect of the reading for that class and then solve the problem or answer the question so stated. -

Goethe and the Dutch Interior: a Study in the Imagery of Romanticism

Goethe and the Dutch Interior: A Study in the Imagery of Romanticism URSULA HOFF THE ANNUAL LECTURE delivered to The Australian Academy of the Humanities at its Third Annual General Meeting at Canberra on 16 May 1972 Australian Academy of the Humanities, Proceedings 3, 1972 PLATES PLATEI J. C. Seekatz, The Goethe Family in Shepherd's Costume (1762). Weimar Goethc National Museum PLATE2 A. v. Ostade, Peasants in an Interior (1660). Dresden Gallery PLATE3 Goethe, Self Portrait in Iris FraiFrt Romn (c. 1768). Drawing, Weimar Goethe National Museum PLATE4 J. Juncker, The Master at his Easel (1752). Kassel Gallery PLATE5 F. v. Mieris the Elder, The Connoisseur in the Artist's Studio (c. 1660-5). Dresden Gallery PLATE6 D. Chodowiecki, Werlher's Roam. Etching, from The Wallrrf-Richartz Jahrbuch, Vol. XXII, fig. 79 PLATE7 G. Terhorch, 'I'Instruction Patemelie1 (1650-5). Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam PLA~8 G. F. Kersting, The Embroidress (1811). Webar Kunstsammlungen PLATE9 J. H. W.Tibein, Goethe from the back lookinp out of a Window over Rome (c. 1787). Weimar Goethe National Museum PLATE10 G. F Kersting, Man Writing by a Window (1811). Weimar Kunstsammlungen PLATE11 G. F. Kersting, Reader by Lamplight (1811). Weimar Kunstsamdimgen PLATE12 G. F. Kersting, C. D. Friedlrich in his Studio (1811). Hamburg Kunsthalle PLATE13 Vincent van Gogh, Bedroom at Arles(188g). Chicago Art Institute The author gratefully acknowledges the kind assistance of the above galleries and museums for permission to reproduce photographs of works from their collections as plates in this paper. Australian Academy of the Humanities, Proceedings 3, 1972 HE theme of this paper is taken from the history of romantic art. -

The Neoclassical Grand Tour of Sicily and Goethe's Italienische Reise

Alman Dili ve Edebiyatı Dergisi – Studien zur deutschen Sprache und Literatur 2017/I Okt. Dr. Cristiano Bedin İstanbul Üniversitesi (Istanbul, Turkey) İtalyan Dili ve Edebiyatı Anabilim Dalı E-Mail: [email protected] The Neoclassical Grand Tour of Sicily and Goethe’s Italienische Reise The Neoclassical Grand Tour of Sicily and Goethe’s Italienische Reise (ABSTRACT ENGLISH) The Grand Tour tradition is a very important phenomenon of the eighteenth- century Europe. During this period, English, French and German aristocrats traveled in Italy for educational purposes. At the same time, in the eighteenth century, Greek ancient culture, art and literature attracted the attention of European intellectuals under the influence of the new aesthetic ideas of the German art historian Winckelmann. For this reason – although the eighteen- century Italian journey generally ended in Naples – some courageous travelers went to Sicily and traveled in this remote and unknown island to discover the remaining ruins of classical Greek civilization. In this period there was a serious increase in travel to Sicily, the center of Greek culture in Italy in ancient times. One of the most important foreign writers who traveled to Sicily and described their travel experience is certainly the German poet and writer Johann W. Goethe. The purpose of this article is to analyse the image of Sicily present in the Italienische Reise by Goethe. Keywords: Goethe, Italienische Reise, Italian journey, Neoclassicism, Antiquity, Sicily. Die neoklassizistische Grand Tour Sizilien und Goethes italienische Reise (ABSTRACT DEUTSCH) Die Grand Tour-Tradition ist ein sehr bedeutendes Phänomen im Europa des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts. Während dieser Epoche unternahmen englische, französische und deutsche Aristokraten Bildungsreisen in Italien. -

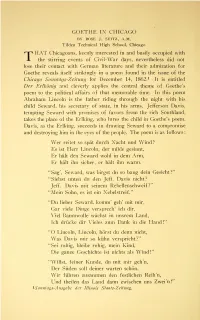

Goethe in Chicago

: GOETHE IN CHICAGO BY ROSE J. SEITZ, A.M. Tilden Technical High School, Chicago THxA.T Chicagoans, keenly interested in and busily occupied with the stirring events of Civil-War days, nevertheless did not lose their contact with German literature and their admiration for Goethe reveals itself strikingly in a poem found in the issue of the Chicago Sonntags-Zeituug for December 14, 1862.1 It is entitled Der Erlkonig and cleverly applies the central theme of Goethe's poem to the political affairs of that memorable time. In this poem Abraham Lincoln is the father riding through the night with his child Seward, his secretary of state, in his arms. Jefiferson Davis, tempting Seward with promises of favors from the rich Southland, takes the place of the Erlking, who lures the child in Goethe's poem. Davis, as the Erlking, succeeds in drawing Seward to a compromise and destroying him in the eyes of the people. The poem is as follows Wer reitet so spat durch Xacht und Wind? Es ist Herr Lincoln, der milde gesinnt, Er halt den Seward wohl in dem Arm, Er halt ihn sicher, er halt ihn warm. "Sag", Seward, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?" "Siehst unten du den Jefif. Davis nicht? ?" Jefif. Davis mit seinem Rebellenschweif "Mein Sohn, es ist ein Nebelstreif." "Du lieber Seward, komm' geh" mit mir, Gar viele Dinge versprech' ich dir. Viel Baumwolle wachst in unsrem Land, !" Ich driicke dir A'ieles zum Dank in die Hand "O Lincoln, Lincoln, horst du denn nicht, Was Davis mir so kiihn verspricht?" "Sei ruhig, bleibe ruhig, mein Kind, !" Die ganze Geschichte ist nichts als Wind "Willst, feiner Kunde, du mit mir geh'n, Der Siiden soil deiner warten schon, Wir fiihren zusammen den festlichen Reih'n, !" L"nd theilen das Land dann zwischen uns Zwei'n '^Sonntags-Ansgabc der Illinois Staats-Zeititng. -

The University of Chicago a Philosophy to Live By

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO A PHILOSOPHY TO LIVE BY: GOETHE‘S ART OF LIVING IN THE SPIRIT OF THE ANCIENTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC STUDIES BY GEORGINNA ANNE HINNEBUSCH CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2018 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations....................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... vii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Goethe and Ancient philosophy .................................................................................................. 6 Philosophy as an Art of Living: Making the most of life ........................................................ 10 Art & Science as a Goethean Art of Living .............................................................................. 18 Introduction of Chapters ........................................................................................................... 19 Chapter 1 Ancient Philosophy as an Art of living........................................................................ 26 Central Claim & Methodology ................................................................................................. 29 Outline of this chapter .............................................................................................................. -

Goethe's Torquato Tasso and James's Roderick Hudson

Erschienen in: Anglia : Journal of English Philology ; 136 (2018), 4. - S. 687-704 https://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ang-2018-0068 Anglia 2018; 136(4): 687–704 Timo Müller* Framing the Romantic Artist: Goethe’s Torquato Tasso and James’s Roderick Hudson https://doi.org/10.1515/ang-2018-0068 Abstract: Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s Torquato Tasso (1790) and Henry James’s Roderick Hudson (1875) share not only a number of structural parallels but also an interest in the fate of the romantic artist in a regulated society. The article suggests Goethe’s play as a possible influence on James’s novel. After a brief outline of James’s relationship to Goethe and of the structural parallels between the texts, the article discusses the similarities of their stance on the romantic artist. Both texts contrast the protagonist’s classicist-idealist art with his broadly romantic personality, both remain ambivalent about the romantic conception of the poet-genius, and both take an analytical attitude toward their artist figures. On this poetological level, the article concludes, their portraits of a proto-Roman- tic and a late Romantic respectively form a revealing historical frame of the phenomenon of the Romantic artist. Henry James’s first Italian journey culminated in his visit to Rome in October 1869. “At last—for the first time—I live!” he wrote to his brother William. “I went reeling and moaning thro’ the streets, in a fever of enjoyment” (James 1974–1980: 160). James was not the first writer, of course, to find inspiration in Italy, but few have responded so enthusiastically. -

Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe (1749-1832): Italian Journey, 1786-7, Published 1816-7

Goethe 1 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832): Italian Journey, 1786-7, published 1816-7 Introductory Note Everybody knows that the thrones of European literature are occupied by the triumvirate referred to in Finnegans Wake as Daunty, Gouty and Shopkeeper, but to most English-speaking readers the second is merely a name. German is a more difficult language to learn to read than Italian, and whereas Shakespeare, apparently, translates very well into German, Goethe is peculiarly resistant to translation into English; Hölderlin and Rilke, for example, come through much better. From a translation of Faust, any reader can see that Goethe must have been extraordinarily intelligent, but he will probably get the impression that he was too intelligent, too lacking in passion, because no translation can give a proper idea of Goethe’s amazing command of every style of poetry, from the coarse to the witty to the lyrical to the sublime. The reader, on the other hand, who does know some German and is beginning to take an interest in Goethe comes up against a cultural barrier, the humorless idolization of Goethe by German professors and critics who treat every word he ever uttered as Holy Writ. Even if it were in our cultural tradition to revere our great writers in this way, it would be much more difficult for us to idolize Shakespeare the man because we know nothing about him, whereas Goethe was essentially an autobiographical writer, whose life is the most documented of anyone who ever lived; compared with Goethe, even Dr Johnson is a shadowy figure.