The Emergence of Chinese Local People's Congresses As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comedy Therapy

VFW’S HURRICANE DISASTER RELIEF TET 50 YEARS LATER OFFENSIVE An artist emerges from the trenches of WWI COMEDYAS THERAPY Leading the way in supporting those who lead the way. USAA is proud to join forces with the Veterans of Foreign Wars in helping support veterans and their families. USAA means United Services Automobile Association and its affiliates. The VFW receives financial support for this sponsorship. © 2017 USAA. 237701-0317 VFW’S HURRICANE DISASTER RELIEF TET 50 YEARS LATER OFFENSIVE An artist emerges from the trenches of WWI COMEDYAS THERAPY JANUARY 2018 Vol. 105 No. 4 COVER PHOTO: An M-60 machine gunner with 2nd Bn., 5th Marines, readies himself for another assault during the COMEDY HEALS Battle of Hue during the Tet Offensive in 20 A VFW member in New York started a nonprofit that offers veterans February 1968. Strapped to his helmet is a a creative artistic outlet. One component is a stand-up comedy work- wrench for his gun, a first-aid kit and what appears to be a vial of gun oil. If any VFW shop hosted by a Post on Long Island. BY KARI WILLIAMS magazine readers know the identity of this Marine, please contact us with details at [email protected]. Photo by Don ‘A LOT OF DEVASTATION’ McCullin/Contact Press Images. After hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria 26 ON THE COVER roared through Texas, Florida and Puer- 14 to Rico last fall, VFW Posts from around Tet Offensive the nation rallied to aid those affected. 20 Comedy Heals Meanwhile, VFW National Headquar- 26 Hurricane Disaster Relief ters had raised nearly $250,000 in finan- 32 An Artist Emerges cial support through the end of October. -

Structure and Law Enforcement of Environmental Police in China

Cambridge Journal of China Studies 33 Structure and Law Enforcement of Environmental Police in China Michael WUNDERLICH Free University of Berlin, Germany Abstract: Is the Environmental Police (EP) the solution to close the remaining gaps preventing an effective Environmental Protection Law (EPL) implementation? By analyzing the different concepts behind and needs for a Chinese EP, this question is answered. The Environmental Protection Bureau (EPB) has the task of establishing, implementing, and enforcing the environmental law. But due to the fragmented structure of environmental governance in China, the limited power of the EPBs local branches, e.g. when other laws overlap with the EPL, low level of public participation, and lacking capacity and personnel of the EPBs, they are vulnerable and have no effective means for law enforcement. An EP could improve this by being a legal police force. Different approaches have been implemented on a local basis, e.g. the Beijing or Jiangsu EP, but they still lack a legal basis and power. Although the 2014 EPL tackled many issues, some implementation problems remain: The Chinese EP needs a superior legal status as well as the implementation of an EP is not further described. It is likely that the already complex police structure further impedes inter-department-cooperation. Thus, it was proposed to unite all environment-related police in the EP. Meanwhile the question will be raised, which circumstance is making large scale environmental pollution possible and which role environmental ethics play when discussing the concept of EPs. Key Words: China, Environmental Police, Law Enforcement, Environmental Protection Law The author would like to show his gratitude to Ms. -

Democratic Centralism and Administration in China

This is the accepted version of the chapter published in: F Hualing, J Gillespie, P Nicholson and W Partlett (eds), Socialist Law in Socialist East Asia, Cambridge University Press (2018) Democratic Centralism and Administration in China Sarah BiddulphP0F 1 1. INTRODUCTION The decision issued by the fourth plenary session of the 18th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP, or Party) in 2014 on Some Major Questions in Comprehensively Promoting Governing the Country According to Law (the ‘Fourth Plenum Decision’) reiterated the Party’s determination to build a ‘socialist rule of law system with Chinese characteristics’.P1F 2P What does this proclamation of the ‘socialist’ nature of China’s version of rule of law mean, if anything? Development of a notion of socialist rule of law in China has included many apparently competing and often mutually inconsistent narratives and trends. So, in searching for indicia of socialism in China’s legal system it is necessary at the outset to acknowledge that what we identify as socialist may be overlaid with other important influences, including at least China’s long history of centralised, bureaucratic governance, Maoist forms of ‘adaptive’ governanceP2F 3P and Western ideological, legal and institutional imports, outside of Marxism–Leninism. In fact, what the Chinese party-state labels ‘socialist’ has already departed from the original ideals of European socialists. This chapter does not engage in a critique of whether Chinese versions of socialism are really ‘socialist’. Instead it examines the influence on China’s legal system of democratic centralism, often attributed to Lenin, but more significantly for this book project firmly embraced by the party-state as a core element of ‘Chinese socialism’. -

Uvic Thesis Template

Corporatist Legislature: Authoritarianism, Representation and Local People‘s Congress in Zhejiang by Jing Qian LL.B., Zhejiang Gongshang University, 2007 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF LAWS in the Faculty of Law Jing Qian, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Corporatist Legislature: Authoritarianism, Representation and Local People‘s Congress in Zhejiang by Jing Qian LL.B., Zhejiang Gongshang University, 2007 Supervisory Committee Dr. Andrew James Harding, Faculty of Law, University of Victoria Co-Supervisor Dr. Guoguang Wu, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria Co-Supervisor iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Andrew James Harding, Faculty of Law, University of Victoria Co-Supervisor Dr. Guoguang Wu, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria Co-Supervisor In this thesis, the author analyzes the role of Local People‘s Congresses (LPCs) in China in shaping state-society relations in a decentralized authoritarian regime. Classical theories of corporatism are applied in order to examine the political functions of the LPC, a local representative and legislative mechanism. The author further proposes expanding the application of corporatist theory to encompass elected representative assemblies. In his analysis, the author explores how the state penetrates into and controls the LPC, and how, at the same time, the local legislature unequally incorporates various social groups into public affairs. He compares and contrasts biased strategies adopted by the state via the LPCs concerning different social sectors, under a dichotomy of inclusionary and exclusionary corporatism, based on which he further suggests a tentative typology of liberal/corporatist/communist legislature to enrich theories of comparative legislative studies. -

Crime Feeds on Legal Activities: Daily Mobility Flows Help to Explain Thieves' Target Location Choices

Journal of Quantitative Criminology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09406-z ORIGINAL PAPER Crime Feeds on Legal Activities: Daily Mobility Flows Help to Explain Thieves’ Target Location Choices Guangwen Song1 · Wim Bernasco2,3 · Lin Liu1,4 · Luzi Xiao1 · Suhong Zhou5 · Weiwei Liao5 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Objective According to routine activity theory and crime pattern theory, crime feeds on the legal routine activities of ofenders and unguarded victims. Based on this assumption, the present study investigates whether daily mobility fows of the urban population help predict where individual thieves commit crimes. Methods Geocoded tracks of mobile phones are used to estimate the intensity of popula- tion mobility between pairs of 1616 communities in a large city in China. Using data on 3436 police-recorded thefts from the person, we apply discrete choice models to assess whether mobility fows help explain where ofenders go to perpetrate crime. Results Accounting for the presence of crime generators and distance to the ofender’s home location, we fnd that the stronger a community is connected by population fows to where the ofender lives, the larger its probability of being targeted. Conclusions The mobility fow measure is a useful addition to the estimated efects of dis- tance and crime generators. It predicts the locations of thefts much better than the presence of crime generators does. However, it does not replace the role of distance, suggesting that ofenders are more spatially restricted than others, or that even within their activity spaces they prefer to ofend near their homes. Keywords Crime location choice · Theft from the person · Mobility · Routine activities · China * Lin Liu [email protected] 1 Center of Geo-Informatics for Public Security, School of Geographical Sciences, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China 2 Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement (NSCR), P.O. -

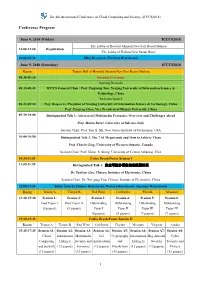

Conference Program

The 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Security (ICCCS2018) Conference Program June 8, 2018 (Friday) ICCCS2018 The Lobby of Howard Johnson New Port Resort Haikou 14:00-21:00 Registration The Lobby of Haikou New Yantai Hotel 18:00-21:30 BBQ Reception (Western Restaurant) June 9, 2018 (Saturday) ICCCS2018 Room Tianjin Hall of Howard Johnson New Port Resort Haikou 08:30-09:10 Opening Ceremony Opening Remarks 08:35-08:45 ICCCS General Chair: Prof. Xingming Sun, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China Welcome Speech 08:45-09:10 Prof. Beiqun Li, President of Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, China Prof. Xianfeng Chen, Vice President of Hainan University, China 09:10-10:00 Distinguished Talk 1: Adversarial Multimedia Forensics: Overview and Challenges Ahead Prof. Mauro Barni, University of Salerno, Italy Session Chair: Prof. Yun Q. Shi, New Jersey Institute of Technolgoy, USA 10:00-10:50 Distinguished Talk 2: The 7 AI Megatrends and How to Achieve Them Prof. Charles Ling, University of Western Ontario, Canada Session Chair: Prof. Victor. S. Sheng, University of Central Arkansas, USA 10:50-11:05 Coffee Break/Poster Session I 11:05-11:55 Distinguished Talk 3: 安全可控多模态信息隐藏体系 Dr. Yunbiao Guo, Chinese Institute of Electronics, China Session Chair: Dr. Xin’gang You, Chinese Institute of Electronics, China 12:00-13:30 Buffet Lunch (Chinese Restaurant, Western Restaurant, Japanese Restaurant) Room Tianjin A Tianjin B Red Wine California Florida Missouri 13:30-15:30 Session 1: Session 2: Session -

China's Environmental Super Ministry Reform

Copyright © 2009 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120. n March 15, 2008, China’s Eleventh National Peo- China’s ple’s Congress passed the super ministry reform (SMR) motion proposed by the State Council and Ocreated five “super ministries,” mostly combinations of two or Environmental more previous ministries or departments. The main purpose of this SMR was to avoid overlapping governmental responsi- Super Ministry bilities by combining departments with similar authority and closely related functions. One of the highlights was the eleva- tion of the State Environmental Protection Administration Reform: (SEPA) to the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), which we also refer to as the environmental SMR. Background, The reference to super ministry is shorthand for the creation of a “comprehensive responsibilities super administrative min- istry framework.”1 In order to promote comprehensive man- Challenges, and agement and coordination, several departments are merged into a new entity, the super ministry, based on their similar the Future goals and responsibilities. By enlarging the ministry’s respon- sibilities and authority, the reform essentially turns some inter- departmental tasks to intradepartmental issues, so one single department can cope with comprehensive problems from by Xin QIU and Honglin LI multiple perspectives, avoiding overlapping responsibilities and authority. Thus, administrative efficiency is increased and Xin QIU is a Ph.D. candidate and visiting fellow administrative costs are reduced. at Vermont Law School. Honglin LI is Director During this SMR, MEP was upgraded and was the only of Law Programs, Yale-China Association.* department to retain its organizational structure and govern- mental responsibilities.2 This demonstrates the strong political will and commitment of China’s central government to envi- Editors’ Summary ronmental protection. -

It's Not What Is on Paper, but What Is in Practice: China's New Labor Contract Law and the Enforcement Problem

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 8 Issue 3 January 2009 It's Not What Is on Paper, but What Is in Practice: China's New Labor Contract Law and the Enforcement Problem Yin Lily Zheng Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Yin Lily Zheng, It's Not What Is on Paper, but What Is in Practice: China's New Labor Contract Law and the Enforcement Problem, 8 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 595 (2009), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol8/iss3/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IT’S NOT WHAT IS ON PAPER, BUT WHAT IS IN PRACTICE: CHINA’S NEW LABOR CONTRACT LAW AND THE ENFORCEMENT PROBLEM INTRODUCTION After decades of implementing a lifetime employment system, China has decided to shift gear and rely on private contracts to regulate domestic labor relations.1 The new Labor Contract Law, which officially took effect on January 1, 2008, memorializes this change.2 Proponents of the new law lauded it as “the most concerted effort to protect workers’ rights.”3 Yet many provisions in the law touched the nerves of quite a few domestic and foreign businesses in China4 and are criticized as overly generous to labor 5 rights. -

![Risks Faced by Foreign Lawyers in China [Article]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5720/risks-faced-by-foreign-lawyers-in-china-article-2105720.webp)

Risks Faced by Foreign Lawyers in China [Article]

Risks Faced by Foreign Lawyers in China [Article] Item Type Article; text Authors Liu, Chenglin Citation 35 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. L. 131 (2018) Publisher The University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law (Tucson, AZ) Journal Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law Rights Copyright © The Author(s) Download date 01/10/2021 04:26:41 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/658799 RISKS FACED BY FOREIGN LAWYERS IN CHINA Chenglin Liu* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................ 131 I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 132 II. A FOREIGN CITIZEN CANNOT BE LICENSED AS A PRACTICING LAWYER IN CHINA .. ......................................................... 135 III. THE REGULATIONS AND RULES ON FOREIGN LAWYERS ........ .......... 136 IV. REGULATIONS AND RULES IN DETAIL ................................. 138 A. Scope of Services ................................. ..... 138 B. Legal Responsibilities ...........................................139 C. Enforcement ..............................................141 V. No OFFICIAL INTERPRETATION OF THE REGULATIONS AND RULES................143 VI. THE PLAIN MEANINGS OF ARTICLE 15(5) OF THE REGULATIONS AND ARTICLE 33 OF THE RULES ................................................ ...... 144 A. The Plain Meaning of the Two Articles Based on the Xinhua Dictionary 144 B. The Plain Meaning of the Two Articles Based on the Chinese -

Biomolecules

biomolecules Article Comparative Analysis of MicroRNA and mRNA Profiles of Sperm with Different Freeze Tolerance Capacities in Boar (Sus scrofa) and Giant Panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) 1, 2, 1, 1 1 1 Ming-Xia Ran y, Ying-Min Zhou y, Kai Liang y, Wen-Can Wang , Yan Zhang , Ming Zhang , Jian-Dong Yang 1, Guang-Bin Zhou 1 , Kai Wu 2, Cheng-Dong Wang 2, Yan Huang 2, Bo Luo 2, Izhar Hyder Qazi 1,3 , He-Min Zhang 2,* and Chang-Jun Zeng 1,* 1 College of Animal Sciences and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China 2 China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda, Wolong 473000, China 3 Department of Veterinary Anatomy & Histology, Faculty of Bio-Sciences, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Sakrand 67210, Sindh, Pakistan * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.-M.Z.); [email protected] (C.-J.Z.); Tel./Fax: +86-28-86291010 These authors contribute equally to this work. y Received: 21 August 2019; Accepted: 29 August 2019; Published: 1 September 2019 Abstract: Post-thawed sperm quality parameters vary across different species after cryopreservation. To date, the molecular mechanism of sperm cryoinjury, freeze-tolerance and other influential factors are largely unknown. In this study, significantly dysregulated microRNAs (miRNAs) and mRNAs in boar and giant panda sperm with different cryo-resistance capacity were evaluated. From the result of miRNA profile of fresh and frozen-thawed giant panda sperm, a total of 899 mature, novel miRNAs were identified, and 284 miRNAs were found to be significantly dysregulated (195 up-regulated and 89 down-regulated). -

"Du Shiniang Sinks Her Jewel Box in Anger": a Story to Defend Folk

"Du Shiniang Sinks Her Jewel Box in Anger": A Story to Defend Folk Literature Presented to the Faculty of the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures Bryn Mawr College In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts By Binglei Yan Advisor: Professor Shiamin Kwa Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania December 2015 Abstract This thesis takes a look at one of the short stories in Feng Menglong's Sanyan collection, "Du Shiniang Sinks Her Jewel Box in Anger." Written during the late Ming dynasty, the story has been typically analyzed by present-day scholars as a political allegory or as a lesson to teach qing, a term which translated alternately as "passions," "love," or "romantic sentiments" in English. Based on the background that the archaic elite literature was advocated through the Ming literary movement called "the restoration of the past" and Feng Menglong, as a follower of key anti-archaists like Wang Yanming, Li Zhi, and Yuan Hongdao, emphasized authentic feelings and spontaneity in literature, this thesis argues that in "Du Shiniang Sinks Her Jewel Box in Anger," Feng Menglong metaphorically defended folk literature by defending Du Shiniang. Through examining the ways in which Feng Menglong praised the courtesan Du Shiniang's spontaneous and sincere nature that embodied in her xia (chivalry) and qing characteristics in the story, it becomes clear that Feng Menglong advocated folk literature as what should be extolled in the late Ming. The thesis concludes by recommending that this Feng Menglong's story is possibly a forerunner of a growing genre in the Qing dynasty which makes it worth for further researches. -

Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals the Differentially Expressed Lncrnas and Mrnas Involved in Cryoinjuries in Frozen-Thawed Giant Panda (Ailuropoda Melanoleuca) Sperm

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals the Differentially Expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs Involved in Cryoinjuries in Frozen-Thawed Giant Panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Sperm Ming-Xia Ran 1,†, Yuan Li 1,†, Yan Zhang 1, Kai Liang 1, Ying-Nan Ren 1, Ming Zhang 1, Guang-Bin Zhou 1, Ying-Min Zhou 2, Kai Wu 2, Cheng-Dong Wang 2, Yan Huang 2, Bo Luo 2, Izhar Hyder Qazi 1,3 , He-Min Zhang 2 and Chang-Jun Zeng 1,* 1 College of Animal Sciences and Technology, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, Sichuan, China; [email protected] (M.-X.R.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (K.L.); [email protected] (Y.-N.R.); [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (G.-B.Z.); [email protected] (I.H.Q.) 2 China Conservation and Research Center for the Giant Panda, Wolong 473000, China; [email protected] (Y.-M.Z.); [email protected] (K.W.); [email protected] (C.-D.W.); [email protected] (Y.H.); [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (H.-M.Z.) 3 Department of Veterinary Anatomy & Histology, Faculty of Bio-Sciences, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Sakrand 67210, Pakistan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +86-28-8629-1010 † These authors contribute equally to this work. Received: 5 September 2018; Accepted: 5 October 2018; Published: 8 October 2018 Abstract: Sperm cryopreservation and artificial insemination are important methods for giant panda breeding and preservation of extant genetic diversity. Lower conception rates limit the use of artificial insemination with frozen-thawed giant panda sperm, due to the lack of understanding of the cryodamaging or cryoinjuring mechanisms in cryopreservation.