The Hillbilly in the Living Room

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2021 Mayberry Magazine

Spring 2021 MayberryMAGAZINE Mayberry Man Andy Griffith Show Movie nearing release A star comes to visit Andy Finds Himself Mayberry Trivia College opened new Test your knowledge world What’s Happening? Comprehensive calendar ISSUE 30 Table of Contents Cover Story — Finally here? Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the much ballyhooed Mayberry Man movie has continued, working around delays, postponements, and schedule changes. Now, the movie is just a few months away from release to its supporters, and hopefully, a public debut not too long afterward. Page 8 Andy finds himself He certainly wasn’t the first student to attend the University of North Carolina, nor the last, but Andy Griffith found an outlet for his creative talents at the venerable state institution, finding himself, and his career path, at the school. Page 4 Guest stars galore Being a guest star on “The Andy Griffith Show” could be a launching pad for young actors, and even already established stars sometimes wanted the chance to work with the cast and crew there. But it was Jean Hagen, driving a fast car and doing some smooth talking, who was the first established star to grace the set. Page 6 What To Do, What To Do… The pandemic put a halt to many shows and events over the course of 2020, but there might very well be a few concerts, shows, and events stirring in Mount Airy — the real-life Mayberry — this spring and summer. Page 10 SPRING 2021 SPRING So, You Think You Know • The Andy Griffith Show? Well, let’s see just how deep your knowledge runs. -

THE WIZARD of OZ an ILLUSTRATED COMPANION to the TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC by John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan with a Foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini

THE WIZARD OF OZ AN ILLUSTRATED COMPANION TO THE TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC By John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan With a foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini The Wizard of Oz: An Illustrated Companion to the Timeless Movie Classic is a vibrant celebration of the 70th anniversary of the film’s August 1939 premiere. Its U.S. publication coincides with the release of Warner Home Video’s special collector’s edition DVD of The Wizard of Oz. POP-CULTURE/ ENTERTAINMENT over the rainbow FALL 2009 How Oz Came to the Screen t least six times between April and September 1938, M-G-M Winkie Guards); the capture and chase by The Winkies; and scenes with HARDCOVER set a start date for The Wizard of Oz, and each came and went The Witch, Nikko, and another monkey. Stills of these sequences show stag- as preproduction problems grew. By October, director Norman ing and visual concepts that would not appear in the finished film: A Taurog had left the project; when filming finally started on the A • Rather than being followed and chased by The Winkies, Toto 13th, Richard Thorpe was—literally and figuratively—calling the shots. instead escaped through their ranks to leap across the castle $20.00 Rumor had it that the Oz Unit first would seek and photograph whichever drawbridge. California barnyard most resembled Kansas. Alternately, a trade paper re- • Thorpe kept Bolger, Ebsen, and Lahr in their Guard disguises well ported that all the musical numbers would be completed before other after they broke through The Tower Room door to free Dorothy. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Beverly Hillbillies: a Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968

Paul Henning; The Beverly Hillbillies: A Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968 The Beverly Hillbillies is an American situation comedy originally broadcast for nine seasons on CBS from 1962 to 1971, starring Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer, Jr. The series is about a poor backwoods family transplanted to Beverly Hills, California, after striking oil on their land. A Filmways production created by writer Paul Henning, it is the first in a genre of "fish out of water" themed television shows, and was followed by other Henning-inspired country-cousin series on CBS. In 1963, Henning introduced Petticoat Junction, and in 1965 he reversed the rags The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 : A nouveau riche hillbilly family moves to Beverly Hills and shakes up the privileged society with their hayseed ways. The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 English Sub | Fmovies. Loading Turn off light Report. Loading ads You can also control the player by using these shortcuts Enter/Space M 0-9 F. Scroll down and click to choose episode/server you want to watch. - We apologize to all users; due to technical issues, several links on the website are not working at the moments, and re - work at some hours late. Watch The Beverly Hillbillies 3 Online. the beverly hillbillies 3 full movie with English subtitle. Stars: Buddy Ebsen, Donna Douglas, Raymond Bailey, Irene Ryan, Max Baer Jr, Nancy Kulp. "The Beverly Hillbillies" is a classic American comedy series that originally aired for nine seasons from 1962 to 1971 and was the first television series to feature a "fish out of water" genre. -

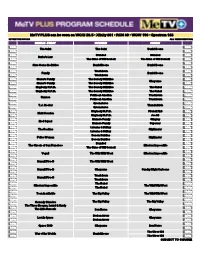

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

New York to Hollywood: Advertising, Narrative Formats, and Changing Televisual Space in the 1950'S

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 New York to Hollywood: Advertising, Narrative Formats, and Changing Televisual Space in the 1950's Peter McCormack Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the United States History Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation McCormack, Peter, "New York to Hollywood: Advertising, Narrative Formats, and Changing Televisual Space in the 1950's" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 148. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/148 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From New York to Hollywood: Advertising, Narrative Formats, and Changing Televisual Space in the 1950’s Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Peter McCormack Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 ii From New York to Hollywood iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents first and foremost. I don’t think I’ve ever taken the time to bore them with the intimate details of this project. -

Calendar of Events 2017 Board Meetings Website Upgrading

Monthly Newsletter for The Tiffany Homeowners Association • A Covenant Protected Community Calendar April 2017 Vol. 12 No. 04 • Circulation: 175 of Events 2017 Upgrading Telecom Lines April 15th: Easter Egg Hunt The Xfinity/Comcast folks are upgrading the Telecom lines from Dry Creek Road 10:30 a.m. In our park to Milwaukee for the Tiffany neighborhood. They are using a horizontal directional April 22nd: Park Clean-up Day drilling, (HDD) machine to drill 4-5 feet below the ground to install new cable and con- 9:00 a.m. In our park duit. The utility easement runs behind the houses and along the property lines between May 26-29: Dumpster Days houses. The contractor should request access before entering your yard or opening a gate. The City of Centennial has issued a building permit for these folks. Call the City June 3: Spring Walk Thru of Centennial if you have any concerns or questions. June 9-10: Annual Yard Sale — Tom Wood July 4th: 4th of July Parade Starts at Milwaukee Way/ Fillmore Circle Park Clean Up Day August 13th: Neighborhood Picnic 5 p.m. In our park & Plant Swap All residents are invited to park clean-up day on Saturday April 22 at 9 a.m. We can pull weeds, pick up trash and sticks, trim bushes, and more. Does your garden need a change this Spring? Bring your unwanted perennials to Board Meetings the park during clean-up day. Trade them for plants someone else brings. Or take some June 19: Board Meeting – 6:30 p.m. -

WIN F Crash Near Parkade

< . > Average Daily Ne^ P t m ^ ^ (T u S a Y, NOVEMSSai 11, I960 Tho Waathar »AOlB BidHTBBN For the Week niOea Fewcaat at D. >. W m Gm $ «r a lb Nev. 6. leee fU ir Mril 4 i^CitHn. la pefine older and milder Low ik sea I Uoyd Bemis o f Boston wUl speak the rear bf a car being driven by 1 3 ,2 7 0 Watkins Delegate Robert A. Miil^ 19, of 84 MIU 8t„ dlabetle^ tncantly developed oral a t l a n t i o mgk iB bbr on "A Dynamic "New England,” AlUdycees com pw m ia appear ‘to have been Mtnfeer «t the Anatt About Town discussing what New England has which in turn waa pushed Into a| FURNACE OIL Banan of dradatiOB. At UConli Rites ^ e d u v e in reducing blood' augur Mancheater~-~4 City of VUlago Charm • 1 to offer new Industry and business, car being driven by Leon G. kah> Automatic DeHvery at a meeting of the kiwanls Club ' A pamd discuaslon on "Enjoying lot, 59, of 86 Park St. To Distribute The Manchester Junior Chamber L T . W OOD C O . Dm H bl* at Home” wUl be held of Manchester next Tuesday noon For Jorgensen (Claarifled AfivortUiag on Pago S) pRicB invt cB im Davis was a passenger in o f Commerce is distributing the Phone MI 8>I12» (TEN PAGES—TV SECTION) MANCHESTER CONN., SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 1960 tjjfinorrow at 8 p.m. at SuaM n^ at the Manchester Country Club. kits aa Its part in National Di VOL. -

Un Tour Du Monde Pour Fêter 2000 Tème

LeMonde Job: WMQ0201--0001-0 WAS LMQ0201-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 01-01-00 T.: 11:09 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:01,11, Base : LMQPAG 15Fap: 100 No: 0277 Lcp: 700 CMYK LE MONDE TÉLÉVISION SEMAINE DU 3 AU 9 JANVIER 2000 MADELEINE MAKUMABANO PETITE CONVERSATION LA DOLCE VITA LE DAKAR Cette FAMILIALE Un film de Fellini, La 22e édition du rallye journaliste Hélène avec Marcello traversera l’Afrique d’ouest à la forte Lapiower Mastroianni en est. A partir du 6 janvier personnalité a filmé et Anita Ekberg. sur France 2 et France 3. a Le grand retour anime sur RFI sa famille, Palme d’or à Page 38 « Le Débat africain », une émission d’origine juive polonaise. Cannes en 1960. politique très populaire Un « judéo-home-movie » Sur France 2. de l’investigation sur le continent. Page 6 irrésistible. Sur Arte. Page 7 Page 13 a Portrait : la dame de RFI La caméra enquête Plusieurs émissions renouent avec l’investigation journalistique à la télévision. Dernière en date : « 90 minutes » sur Canal+. Pages 4-5 www.lemonde.fr 56e ANNÉE – No 17087 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE DIMANCHE 2 - LUNDI 3 JANVIER 2000 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI aaaaaaaaaaaSUPPLEMENT Les années Eltsine PPARATCHIK du parti devenu le viennes, banni le vieux PC, libéré les prix pouvoir, à l’intérieur comme à l’extérieur, premier président de la Russie sinon l’économie, fait admettre la Russie malgré la sinistre démonstration de force indépendante élu au suffrage dans les organisations internationales où organisée depuis l’automne contre la Tché- A les Occidentaux se retrouvaient naguère tchénie. -

Crossroads Film and Television Program List

Crossroads Film and Television Program List This resource list will help expand your programmatic options for the Crossroads exhibition. Work with your local library, schools, and daycare centers to introduce age-appropriate books that focus on themes featured in the exhibition. Help libraries and bookstores to host book clubs, discussion programs or other learning opportunities, or develop a display with books on the subject. This list is not exhaustive or even all encompassing – it will simply get you started. Rural themes appeared in feature-length films from the beginning of silent movies. The subject matter appealed to audiences, many of whom had relatives or direct experience with life in rural America. Historian Hal Barron explores rural melodrama in “Rural America on the Silent Screen,” Agricultural History 80 (Fall 2006), pp. 383-410. Over the decades, film and television series dramatized, romanticized, sensationalized, and even trivialized rural life, landscapes and experiences. Audiences remained loyal, tuning in to series syndicated on non-network channels. Rural themes still appear in films and series, and treatments of the subject matter range from realistic to sensational. FEATURE LENGTH FILMS The following films are listed alphabetically and by Crossroads exhibit theme. Each film can be a basis for discussions of topics relevant to your state or community. Selected films are those that critics found compelling and that remain accessible. Identity Bridges of Madison County (1995) In rural Iowa in 1965, Italian war-bride Francesca Johnson begins to question her future when National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid pulls into her farm while her husband and children are away at the state fair, asking for directions to Roseman Bridge. -

THE WHISTLER: Notes on Murder Simpson, Tom Brown, Britt Wood, Jeanne Bates, Lawrence Dobkin

Project1:8 Page Booklet 4/30/08 2:24 PM Page 1 Julie from the plan but his actions set his plan spinning out of control. With Bill Forman, Lamont Johnson, Gloria Ann THE WHISTLER: Notes on Murder Simpson, Tom Brown, Britt Wood, Jeanne Bates, Lawrence Dobkin. Program Guide by Jim Widner CD 10A - “Final Papers” – 8/24/1952 – Anna Craig, a European immigrant with a shady past, has gotten the news On May 16th, 1942 a new mystery that she will soon become a citizen. Immigration lawyer, program called The Whistler aired over Stanley Craig is Anna’s husband and knows nothing of her the Columbia Broadcasting System’s past. Lisa Felder, another immigrant with a shady past, West Coast network. The stories for the threatens to reveal Anna’s past unless she convinces her husband to take on her case. Fearful, Anna poisons Lisa rather series were anthologized morality plays than succumb to the threat. When Stanley tells Anna he has to about everyday individuals caught in a go to Europe to investigate Lisa’s past, Anna decides to kill her web of their own making, and tripped up husband to avoid his discovering her own past but her methods by a twist of fate in the end. Heard soon reveal her crimes. With Bill Forman, Gail Bonney, throughout each radio play, as the events William Conrad Gladys Holland, Joseph Kearns, John Stevenson. became a tangled web of crime, was a shadowy voice-of-fate. Dripping with CD 10B - “The Secret of Chalk Point” – 9/7/1952 – Kay Fowler, staying at the Yaeger House at sarcasm, it preached to listeners about the Chalk Point meets a young man on the beach during a heavy fog who says he is the husband of old futility of the criminal act they’d just Mrs. -

Body Lies in NY Armory

1 turn, tcapentu* tf. Partly dndy W^jr, Ufh la te Sfe, T*. BED BANK TODAY •ttt, ctatfy, dunw cf rfwwm, 23,600 tow M. Twawrsw, tetr, Ugh it *• Mt. ThaUty, Itii md CML tioaotmnitin-vn.mt Urn VMtfaer, ***• t DIAL 741-0010 Utatd «tu;. Ibn4u> Ihnash Fittir. SMOB« CUM Pwitp PAGE ONE VOL. 86, NO. 200 P«M tt tUd B4nk ul U Mdllloaai M*Uln» Otflet*. RED BANK, N. J., TUESDAY, APRIL 7, 1964 7c PER COPY GOP Maps Mac Arthur•« Go-It-Alone Fiscal Study Body Lies In TRENTON (AP) - The Republican majority of tha New Jersey Legislature has decided on a go-it-alone policy in setting up an economy study of state government. Republican leaders of the Senate and Assembly met yester- day and decided to reject Gov. Richard J. Hughes' suggestions about the study, made in a conditional veto last month. The N.Y. Armory decision also eliminates chances of a $50,000 appropriation (or the study commission, since the Democratic governor's ap- NEW YORK (AP)-A shriveled Washington after three major op- conflicts as World War I and II. proval ^s required for such spending. yet somehow majestic figure in erations. Yesterday the body lay at the Senate Majority Leader William E. Ozzard, R-Somerset, simple sun tan uniform lay in a Clergymen expected to pray at Universal Funeral Chapel, Lex- laid the commission would operate on funds scraped up from history-laden armory today, a the casket in the armory on Park ngton '.ve. and 52nd St., not far the Legislature's regular budget.