New York to Hollywood: Advertising, Narrative Formats, and Changing Televisual Space in the 1950'S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

The Personal Branding of Lucille Ball Honors Thesis

BLAZING THE TRAILS: THE PERSONAL BRANDING OF LUCILLE BALL HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors College of Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors College by Sarah L. Straka San Marcos, Texas December, 2016 BLAZING THE TRAILS: THE PERSONAL BRANDING OF LUCILLE BALL by Sarah L. Straka Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Dr. Raymond Fisk, Ph.D. Department of Marketing Approved: _________________________________ Heather C. Galloway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors College TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………….…………..…………………iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….….…….1 II. CHILDHOOD………………………………………………………….……...1 III. REBEL………………………………………………………………….….…4 IV. LEADER……………………………………………………...……….....….14 V. ICON……………………………………………………………...………..…17 VI. CONCLUSION……………………………………….............................….18 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………..........20 CHRONOLOGICAL TIME LINE OF LUCILLE BALL…………………...…..........…21 iii ABSTRACT The extraordinary Lucille Ball was the most loved and iconic television comedian of her time. She was an American icon and the first lady of television during the 1950s. Not only did Lucille Ball provide laughter to millions of people, but Lucille Ball gave women a voice and America heard what she had to say. She showed women they can be accepted, and be in a position both on television and in the working world where they can be strong and independent. She was a leader and set an example for women and showed society that women have a voice to be heard and will be successful, when given the opportunity. Lucille Ball managed her career and created her personal brand by beating all obstacles that were laid in front of her and test boundaries, which lead her to become an entrepreneurial success. Lucille Ball blazed the trails for many women, on and off stage. -

CPY Document

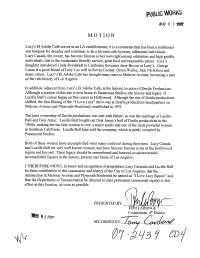

PUBUC WORKS AUG 0 1 ZO MOTION Lucy's El Adobe Café serves as an LA establisluent; it is a restaurant that has been a traditional star hangout for decades and continues to be a favored café by many influential individuals. Lucy Casada, the owner, has become famous in her own right among celebrities and high profie individuals, due to the restaurants friendly service, great food and reasonable prices. Lucy's daughter introduced Linda Rondstadt to California Governor Jerry Brown at Lucy's. George Lucas is a good friend of Lucy's as well as Kevin Costner, Orson Welles, Jack Nicholson and many others. Lucy's El Adobe Café has brought many stars to Melrose Avenue, becoming a part of the rich history of Los Angeles. In addition, adjacent from Lucy's El Adobe Café, is the historic location ofDesilu Productions. Although a portion of this site is now home to Paramount Studios, the history and legacy of Lucille Ball's career began on this comer in Hollywood. Although the site ofDesilu productions shifted, the first fiming of the "I Love Lucy" show was at Desilu productions headquarters on Melrose A venue and Plymouth Boulevard, established in 1951. The joint ownership ofDesilu productions was met with failure, as was the marriage of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. Lucile Ball bought out Desi Arnaz's half ofDesilu productions in the 1960's, making her the first woman to own a major studio and one of the most powerful women in Southern California. Lucile Ball later sold the company, which is partly occupied by Paramount Studios. -

Download the Playbill

The 2018/2019 Season is generously sponsored by This production is generously sponsored in part by Carol Beauchamp, Kathy Gaona, Ronni Lacroute Diane Lewis, Linda Morrisson, Pat Reser & Bill Westphal & Jan Simmons OCT 4,5,6,7,11,12,13,14,18,19,20,21,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 DIRECTOR’S NOTES By Scott Palmer IRA LEVIN is no stranger to murder, his attention successfully to Broadway. upper crust New England convention; mayhem, terror, demons, the He adapted a now-forgotten book by Mac Ralph Lauren woolen sweaters, classical supernatural, or good old-fashioned blood Hyman – No Time For Sergeants – and the architecture, an attractive and supportive and gore. In fact, Levin’s career was 1955 play ran for over 700 performances wife, influential neighbors, with just a largely based on scaring the pants off on Broadway, launching the career of the hint of celebrity here and there; a fading people, and his iconic play, Deathtrap, is lead actor, Andy Griffith. Levin stayed with career and the recognition that younger, perhaps his greatest achievement. theatre for the next 10 years, although more energetic talents may soon eclipse less successfully. His work may not have you. In so many ways, these characters According to the UK’s Independent been hugely impactful for the theatre, are pretty commonplace. newspaper, Ira Levin was “the king of but it was for a number of Broadway the high-concept thriller.” Although he stars. Interlock (1958) starring Maximilian But underneath all of that convention produced more plays than he did novels Schell ran for four performances. -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

Mr. Television

ZXAUncle Miltie.finaledit 2/21/02 11:26 AM Page 2 MR. TELEVISION ncle Miltie would do gave his all.You had to love anything for a laugh. him. He insisted on it. He jumped onstage in Berle had been one of the outlandish costumes— guest hosts of the Texaco Star sometimes in drag. Theater when it began in the HeU would have pies and spring of 1948, and he took powder puffs and buckets of over as permanent host begin- water thrown into his face. ning with the fall premiere. He would fall over face down— He was an immediate hit— hard—or backward, like a piece literally the reason many families of wood. He would tell jokes decided to buy a television that ranged from the obvious set. He became known as to the ridiculous, and when “Mr.Television” because he a joke died, he would mug, dominated the small screen in cajole, milk, or beg the his era, but the moniker stuck audience until they laughed. because he was an innovator— As an entertainer, he wanted one of the first comedians to to please, so much so that he really understand how to use the medium. Early television audiences had never seen anything like Texaco Star Theater before, even if they had seen Berle on Broadway or the vaudeville stage. From the moment the Texaco Service Men launched into the opening jingle (“Oh, we’re the men from Texaco”) to the end of the show (when he sang his theme song,“Near You”),Uncle Miltie worked tirelessly to entertain, bringing 36 ZXAUncle Miltie.finaledit 2/21/02 11:26 AM Page 3 a frantic and infectious energy Berle away from NBC, Berle was a physical comic to the screen. -

Peter Greene Holbrook April 13, 1940 - June 22, 2016

Peter Greene Holbrook April 13, 1940 - June 22, 2016 Peter Holbrook was born in New York City, NY. He attended Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts _and received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Dartmouth College in1961. Peter was born an artist-winning his first award at the age of 7 in the 1s1 grade. His first solo exhibition was at the Carpenter Galleries at Dartmouth College in 1960. Peter in his studio (Photo by Fred Bauer) Following graduation, Peter spent 2 years traveling around Europe, Africa, the Middle East and India. Upon his return to the United States, he enrolled in the Brooklyn Museum Art School. For seven years he worked a variety of jobs in Chicago, from draftsman to taxi driver, and began to exhibit his art work professionally and lecture at the Unive.rsity of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus. It was during this period that photorealism began to emerge as a counter to abstract expressionism. This genre suited Peter's dual interests in photography and painting, although his own approach was to use deliberately applied brushwork and line to suggest the landscape rather than replicate it. In an interview with Rosemary Carstens for an article in Southwest Art magazine, Peter states: "I have always admired the great realists. There's a basic visual magic in the ability of pigment to credibly translate a three-dimensional world into a flat two-dimensional world on paper and canvas. A good painting allows us to momentarily enter another's consciousness and implies dimensions beyond what is normally seen. It makes painting a spiritual exercise, requiring imagination to create credibility." Peter decided he had had enough of city life and came West to California in 1970, bought land in Briceland in Humboldt County and began to build his home. -

The Audiences and Fan Memories of I Love Lucy, the Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family

Viewers Like You: The Audiences and Fan Memories of I Love Lucy, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and All in the Family Mollie Galchus Department of History, Barnard College April 22, 2015 Professor Thai Jones Senior Thesis Seminar 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: I Love Lucy: Widespread Hysteria and the Uniform Audience...................................20 Chapter 2: The Dick Van Dyke Show: Intelligent Comedy for the Sophisticated Audience.........45 Chapter 3: All in the Family: The Season of Relevance and Targeted Audiences........................68 Conclusion: Fan Memories of the Sitcoms Since Their Original Runs.........................................85 Bibliography................................................................................................................................109 2 Acknowledgments First, I’d like to thank my thesis advisor, Thai Jones, for guiding me through the process of writing this thesis, starting with his list of suggestions, back in September, of the first few secondary sources I ended up reading for this project, and for suggesting the angle of the relationship between the audience and the sitcoms. I’d also like to thank my fellow classmates in the senior thesis seminar for their input throughout the year. Thanks also -

The Little Theatre-On the Square, Sullivan SEASON

The Little Theatre-On The Square, Sullivan "Central IllinoIs' Only Star Equity MusIc and Drama Theatre" Guy S. Little, Jr. presents 20 TH SEASON Established 1957 Guy S. Little, Jr, presents MICHAEL CALLAN in MEREDITH WILLSON'S "THE MUSIC MAN" Book, Music & Lyrics by: StDry by: MEREDITH MEREDITH WILLSON and WILLSON FRANKLIN LACEY with MELLISS KENWORTHY JOHN KELSO MARTHA LARRIMORE JOHN GALT Janet Peltz Phil Courington Steve Vujovic Robert Swan I Directed by ROBERT BAKER I Choreographed by HELEN BUTLEROFF Musical Direction by BRUCE KIRLE Production Designed by ROBERT D. SOULE Costumes Designed by DAVI D BESS Lighting Designed by Michael Ritoli Production Stage Manager Technical Director Assistant Musical Director Lee Geisel Michael Ritoli Robert Rodgers ENTIRE PRODUCTION UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF MR. LITTLE Cast Conductor JOHN SCOTT Charlie Cowell ......................................•.. STEPHEN ARNOLD Harold Hill MICHAEL CALLAN Mayor Shinn ...................•.......................JOHN KELSO Ewart Dunlop ..........................••........•.... PHIL COURINGTON Oliver Hix ...........................•....•........... WAYNE BAAR Jacey Squires STEVE VUJOVIC Olin Britt .........................•......•..•.......•. ROBERT SWAN Marcellus Washburn JOHN GALT Tommy Djilas ....................•.•................•..JOHN SCOTT Marion Paroo MELLISS KENWORTHY Mrs. Paroo .........................................•.. JANET PELTZ Amaryllis ......•.•.................................... DORLISA MARTIN Winthrop Paroo ............•.........................•. -

Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S

TV/Series 10 | 2016 Guerres en séries (II) “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S. Military Sitcoms (1955-75) Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1764 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.1764 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S. Military Sitcoms (1955-75) », TV/Series [Online], 10 | 2016, Online since 01 December 2016, connection on 05 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1764 ; DOI : 10.4000/ tvseries.1764 This text was automatically generated on 5 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and t... 1 “‘War… What Is It Good For?’ Laughter and Ratings”: Sgt. Bilko, M*A*S*H and the Heyday of U.S. Military Sitcoms (1955-75) Dennis Tredy 1 If the title of this paper quotes part of the refrain from Edwin Starr’s 1970 protest song, “War,” the song’s next line, proclaiming that war is good for “absolutely nothing” seems inaccurate, at least in terms of successful television sitcoms of from the 1950s to the 1970s. In fact, while Starr’s song was still an anti-Vietnam War battle cry, ground- breaking television programs like M*A*S*H (CBS, 1972-1983) were using laughter and tongue-in-cheek treatment of the horrors of war to provide a somewhat more palatable expression of the growing anti-war sentiment to American audiences. -

American Heritage Center

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER GUIDE TO ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY RESOURCES Child actress Mary Jane Irving with Bessie Barriscale and Ben Alexander in the 1918 silent film Heart of Rachel. Mary Jane Irving papers, American Heritage Center. Compiled by D. Claudia Thompson and Shaun A. Hayes 2009 PREFACE When the University of Wyoming began collecting the papers of national entertainment figures in the 1970s, it was one of only a handful of repositories actively engaged in the field. Business and industry, science, family history, even print literature were all recognized as legitimate fields of study while prejudice remained against mere entertainment as a source of scholarship. There are two arguments to be made against this narrow vision. In the first place, entertainment is very much an industry. It employs thousands. It requires vast capital expenditure, and it lives or dies on profit. In the second place, popular culture is more universal than any other field. Each individual’s experience is unique, but one common thread running throughout humanity is the desire to be taken out of ourselves, to share with our neighbors some story of humor or adventure. This is the basis for entertainment. The Entertainment Industry collections at the American Heritage Center focus on the twentieth century. During the twentieth century, entertainment in the United States changed radically due to advances in communications technology. The development of radio made it possible for the first time for people on both coasts to listen to a performance simultaneously. The delivery of entertainment thus became immensely cheaper and, at the same time, the fame of individual performers grew. -

Lucille Ball and the Vaudeville Heritage of Early American Television Comedy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Citation: White, Rosie (2016) Funny peculiar: Lucille Ball and the vaudeville heritage of early American television comedy. Social Semiotics, 26 (3). pp. 298-310. ISSN 1035-0330 Published by: Taylor & Francis URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2015.1134826 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2015.1134826> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/25818/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published