Jackson, Jimmie Lee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jimmie Lee Jackson and the Events in Selma

Jimmie Lee Jackson and the Events in Selma On the night of February 18, 1965 a group of African-Americans gathered at a church in Marion, Alabama. Among those individuals at Zion's Chapel Methodist Church was Jimmie Lee Jackson, a Vietnam-War veteran. Fighting for his country, however, was not enough in the segregated South for 29-year-old Jimmie Lee to vote. He had tried to register, for several years, but there was always some reason during the Jim-Crow era to keep him from becoming a registered voter. Inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., people in Marion—a town close to Selma—met to talk about how to change things. Why should American citizens be denied the right to vote when the U.S. Constitution allowed it? There was a special purpose for the gathering on February 18th. A young civil-rights activist named James Orange, a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was incarcerated at the Perry County jail. Cordy Tindell ("C. T.") Vivian, a close friend of Dr. King, was planning to lead a group of around 500 peaceful protesters on a walk to the nearby jail. When the marchers reached the post office, they were met by Marion City police officers, sheriff's deputies and Alabama State Troopers who’d formed a line preventing the protestors from moving forward. Somehow the street lights were turned off (to this day it’s not clear how that happened). Under cover of darkness, the police started to beat the marching protestors. Among the injured were Richard Valeriani, a White-House journalist for NBC News, and two cameramen who worked for United Press International. -

Us Department of Justice

u.s. Department of Justice Office of Legislat ive Affairs Oflice of the Assistant Attorney Ge neral Washil1grull. D.C 20530 NOV 09 2012 The Honorable Joseph R. Biden, Jr. President of the Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Mr. President: Pursuant to the Emmett Ti ll Unsolved Civil Ri ghts Cri mes Act of2007 (P.L. 110-3 44), we are pleased to transmit to you a report to Congress on the Department 's activities regarding civil rights era homicides. Please do not hesi tate to contact this office if we may be of additional assistance regarding thi s or any other matter. Sincerely, Jct:.Le~ Acting Assistant Attorney General Enclosure u.s. Department of Justice Office of Legislative Affairs Offi!.:e o f the Assistant Allomey Gl:m:nll Wushingtoll. /J,e. 10530 NOV 09 2012 The Honorable Harry Reid Majority Leader United States Senate Washington, D.c' 20510 Dear Mr. Leader: Pursuanllo the Emmett Ti ll Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act of2007 (P.L. 110-344), we are pleased to transmit to you a report to Congress on the Department's activities regarding civil rights era homicides. Please do not hesi tate to contact this office if we may be of additional assistance regarding this or any other matter. Sincerely, JJ:;A::el~ Acting Assistant Attorney General Enclosure U.S. Department of Justice Office of Legislat ive Affairs Onice of the A ssi~ t a nt /llIome) Genel'lll Wos/tmgtQrI. J) C 10530 NOV 09 lOll The Honorable Mitch McConnell Minority Leader United States Senate Washington, D.C. -

The Attorney General's 4Th Annual Report To

u.s. Department of Justice Office of Legislat ive Affairs Oflice of the Assistant Attorney Ge neral Washil1grull. D.C 20530 NOV 09 2012 The Honorable Joseph R. Biden, Jr. President of the Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Mr. President: Pursuant to the Emmett Ti ll Unsolved Civil Ri ghts Cri mes Act of2007 (P.L. 110-3 44), we are pleased to transmit to you a report to Congress on the Department 's activities regarding civil rights era homicides. Please do not hesi tate to contact this office if we may be of additional assistance regarding thi s or any other matter. Sincerely, Jct:.Le~ Acting Assistant Attorney General Enclosure u.s. Department of Justice Office of Legislative Affairs Offi!.:e o f the Assistant Allomey Gl:m:nll Wushingtoll. /J,e. 10530 NOV 09 2012 The Honorable Harry Reid Majority Leader United States Senate Washington, D.c' 20510 Dear Mr. Leader: Pursuanllo the Emmett Ti ll Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act of2007 (P.L. 110-344), we are pleased to transmit to you a report to Congress on the Department's activities regarding civil rights era homicides. Please do not hesi tate to contact this office if we may be of additional assistance regarding this or any other matter. Sincerely, JJ:;A::el~ Acting Assistant Attorney General Enclosure U.S. Department of Justice Office of Legislat ive Affairs Onice of the A ssi~ t a nt /llIome) Genel'lll Wos/tmgtQrI. J) C 10530 NOV 09 lOll The Honorable Mitch McConnell Minority Leader United States Senate Washington, D.C. -

Scanned Document

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Legi ... lath e Affair ... SEP 23 2011 The Honorable Joseph R. Bidell, Jr. Presi dent Pro Tempore United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Mr. President : Enclosed please find a report to Congress about the Department's activities regarding civil rights era homicides, as requi red by the Emmell Till Unsolved Civil Rights Cri mes Act of 2007. Sincerely. Ronald Weich Assistant Attomey General Enclosure THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S THIRD ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACT OF 2007 AUGUST 2011 -2 INTRODUCTION This report is submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007 ("The Till Act"). I This third Department ofJustice ('"001" or "Oepartmenf') Report is updated with the Department's activities in the year since the second report2 and summarizes prior Department activities in order to present a comprehensive picture ofthe Department 's eITorts regarding unsolved civil rights murders predating December 31,1969. Section I of the Report gives a history of the Department's civil rights cold case work and provides an overview of the factual and legal chall enges we face in our ongoing efforts to prosecute unsolved civil rights era homicides. Since the last report, Department attorneys and FBI agents worked with local official s to bring a successful state prosecution: participated in a local grand jury investigation with a fed eral prosecutor cross-designated as a deputy di strict attorney; success fully defended one ofour federal co nvictions on appellate review; interviewed potential witnesses; and reviewed thousands of pages ofdocuments, files, news accounts, and evi dence. -

Captain Trooper James Bonard Fowler Alabama State Police, Marion,Alabama

CIVIL RJGHTS DIVISION Notice to Close File File No. 144-3-1422 Date MAY 0 3 2011 To: Chief, Criminal Section Re: Captain Trooper James Bonard Fowler Alabama State Police, Marion, Alabama - Subject; Jimmie Lee Jackson (Deceased) - Victim CIVIL RIGHTS It is recommended that the above case be closed for the following reasons: Case Synopsis On February 18, 1965, Alabama State Trooper James Fowler, fatally shot Jimmie Lee Jackson, the 26-year-old African-American victim, following a civil rights protest in Marion, Alabama. The victim was transported to a nearby hospital where he died on February 26, 1965, of an abdominal infection secondary to a gunshot wound to the abdomen. Shelly Ward Attorney To: Records Section Office of Legal Administration The above file has been closed as of this date. Date Chief, Criminal Section XXX -2- Prior to the shooting, approximately 500 African-American members of the community gathered at the Zion Methodist Church to protest the incarceration of a young civil rights worker. Following the meeting at the church, the African-Americans planned to march towards the city jail a half-block away. According to witness accounts and media reports, the protesters were met by a wall of police officers and state troopers who ordered them to disperse, then began beating them with nightsticks. Most of the protestors were chased back into the church, but a small group of them broke away and entered a nearby cafe. According to the subject, he entered the cafe and went to the assistance of a trooper who was being assaulted by a woman with a glass bottle and two men, one of whom was the victim. -

Archbishop Iakovos and the Greek Orthodox Church

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations January 2018 A Quest For Human Rights And Civil Rights: Archbishop Iakovos And The Greek Orthodox Church Michael Varlamos Wayne State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Varlamos, Michael, "A Quest For Human Rights And Civil Rights: Archbishop Iakovos And The Greek Orthodox Church" (2018). Wayne State University Dissertations. 2079. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/2079 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. A QUEST FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND CIVIL RIGHTS: ARCHBISHOP IAKOVOS AND THE GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH by MICHAEL VARLAMOS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2018 MAJOR: HISTORY Approved By: Advisor Date © COPYRIGHT BY MICHAEL VARLAMOS 2018 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my wife Tina and our children Niko, Olivia, Stavroula, Panayiotis, and George ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Having completed this dissertation in partial fulfillment of a doctoral degree in history at Wayne State University, I am deeply indebted to numerous people and institutions who have aided me in various ways to realize this life-long dream and who helped make this work possible. I wish to thank His Eminence Metropolitan Nicholas of the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Detroit who permitted me to pursue both a Master of Arts degree in classics and a doctoral degree in history while serving as the senior priest of the Assumption Church in St. -

Discussion Resource for the Movie SELMA

“From Selma to Ferguson: A Sacred Conversation on Race” Discussion Resource for the Movie SELMA The Racial Justice Ministries Connecticut Conference of the United Church of Christ February 2015 Black History Month Resources: Excellent Leaders Serving Vibrant Congregations Racial Justice Ministries CT Conference United Church of Christ 1 Table of Contents Title Page……………………………………………………………………………………..1 Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………………………….2 A Note to Facilitators……..…………………………………………………………………………….3-4 Selma to Ferguson: A Sacred Conversation on Race Outline………………………….5 Questions……………………………….……………………………………………………6-8 Exploring…How we feel…………………………………………………………….6 Exploring…What we think….………………………………………………………7 Exploring…What will we do…..……………………………………………………8 Facilitator Resources…………..……………………………………………………….....9-13 Definitions……………………………………………………………………………9 Background Information on Historic Individuals and Events………………….10-12 Background information on Contemporary Individuals and Organizations....13-15 Prayer for Facilitators………………………………………………………………………..16 Black History Month Resources: Excellent Leaders Serving Vibrant Congregations Racial Justice Ministries CT Conference United Church of Christ 2 A note to facilitators Gentle – Be gentle with yourself as you prepare to lead this conversation. This film is difficult to watch and the contemporary comparisons are heartbreaking to acknowledge. Tips: Wear comfortable clothes and be sure to provide “Comfort Food” for yourself and participants. (It is much more difficult to argue when we are at table together.) Prayer- Conversations that address the reality of racism are difficult. We have the benefit of having these conversations within a faith-based context. One of the gifts of our context is the ability to pray prior to, during and at the conclusion of the dialog. Tips: Begin the conversation with a written prayer (be sure to name the spirit and attitude you hope to foster in the dialog). -

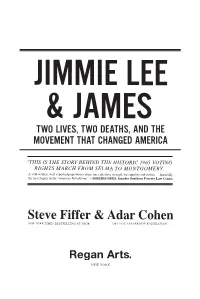

Steve Fiffer & Adar Cohen

JIMMIE LEE JIMMI& JAMESE LEE JIMMI& JAMESE LEE & JAMES TWO LIVES, TWO DEATHS, AND THE MOVEMENT THAT CHANGED AMERICA “THIS IS THE STORY BEHIND THE HISTORIC 1965 VOTING RIGHTS MARCH FROM SELMA TO MONTGOMERY. A well-written, well-reported page turner about our collective struggle for equality and justice … hopefully the last chapter in the American Revolution.” —MORRIS DEES, founder Southern Poverty Law Center “THIS IS THE STORY BEHIND THE HISTORIC 1965 VOTING RIGHTS MARCH FROM SELMA TO MONTGOMERY. A well-written, well-reported page turner about our collective struggle for equality and justice … hopefully Stevethe last chapter in the AmericanFiffer Revolution.” —MORRIS & DEES,Adar founder Southern Cohen Poverty Law Center NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF CIVIC LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION Steve Fiffer & Adar Cohen NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF CIVIC LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION “THIS IS THE STORY BEHIND THE HISTORIC 1965 VOTING RIGHTS MARCH FROM SELMA TO MONTGOMERY. A well-written, well-reported page turner about our collective struggle for equality and justice … hopefully the last chapter in the American Revolution.” —MORRISNEW YORK DEES, founder Southern Poverty Law Center Steve Fiffer & Adar Cohen NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF CIVIC LEADERSHIP FOUNDATION 32691 Jimmie Lee and James_text_3P.indd 3 3/20/15 4:40 PM 65 Bleecker Street New York, NY 10012 Copyright © 2015 by Steve Fiffer and Adar Cohen All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Regan Arts Subsidiary Rights Department, 65 Bleecker Street, New York, NY 10012. First Regan Arts hardcover edition, May 2015 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955556 ISBN 978-1-941393-48-2 Interior design by William Ruoto Jacket and Cover design by Richard Ljoenes Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 32691 Jimmie Lee and James_text_3P.indd 4 3/20/15 4:40 PM To those who marched, and those still marching. -

Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-67

Copyright by Michael William O’Brien 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Michael William O’Brien Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-67 Committee: Mary Beltrán, Supervisor Mia Carter Shanti Kumar Thomas Schatz Janet Staiger Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-67 by Michael William O’Brien Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people, without whom this dissertation would not have been possible: Mary Beltrán, Mia Carter, Janet Staiger, Tom Schatz, Shanti Kumar, Matthew Bernstein, Michele Schreiber, Daniel Contreras, Steve Fogleman, Marten Carlson, Martin Sluk, Hampton Howerton, Paul Monticone, Colleen Montgomery, Collins Swords, Asher Ford, Marnie Ritchie, Ben Philipe, Mike Rennett, Daniel Krasnicki, Charmarie Burke, Mona Syed, Miko, my students, and my family. iv Abstract Third Cinema in the United States, 1960-1967 Michael William O’Brien, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2019 Supervisor: Mary Beltrán This dissertation explores how cinema was an important outlet that artists and activists in the 1960s turned to in order to engage in cultural battles against various forms of institutional oppression. It links the aims and struggles of Americans making socially conscious films about racial discrimination to a broader category of image warfare known as Third Cinema. Third Cinema is generally applied to the notable proliferation of politically engaged films and revolutionary filmmaking theories developed in economically depressed and/or colonially exploited countries. -

Selma to Montgomery Marches - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 7

Selma to Montgomery marches - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 7 Selma to Montgomery marches From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The three 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a landmark achievement of the 1960s American Civil Rights Movement. All three protest Selma to Montgomery marches marches were attempts to walk the 54-mile highway from Selma to the Alabama state capital of Part of Civil Rights Movement Montgomery. The voting rights movement in Selma was launched by local African-Americans, who formed the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL). Joined by organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), they began registering black voters in 1963. When white resistance to their work proved intractable, the DCVL turned to Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, who brought many prominent civil rights and civic leaders to Selma in January 1965. The following month Jimmie Lee Jackson, a voting-rights activist, was mortally wounded during a march in Marion, Alabama, inflaming community passions. To defuse and refocus the anger, SCLC Director of Direct Action James Bevel, who was directing SCLC's Selma Campaign, called Alabama State troopers attack civil-rights [1][2] for a march of dramatic length, from Selma to Montgomery. demonstrators outside Selma, Alabama, on Bloody The first march took place on March 7, 1965; it gained the nickname "Bloody Sunday" after its Sunday, March 7, 1965 600 marchers were attacked by state and local police with billy clubs and tear gas. The second Date March 7, 1965 – March 25, 1965 march took place March 9; police and marchers stood off against one another, but when the Location Edmund Pettus Bridge, U.S. -

Timeline: the Selma Voting Rights Campaign

TIMELINE: THE SELMA VOTING RIGHTS CAMPAIGN 1962 – 63 • The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Begins Organizing in Selma NOV. 1962 NSNCC leaders Bernard and Colia Liddel Lafayette arrive in Selma. A leader in the Nashville student movement, Lafayette connects with members of the Dallas County Voters League, including League president, S.W. Boynton, and his wife and colleague, Amelia Boynton, who first began organizing in the 1930s. JAN. – OCT. 1963 SNCC organizers Bernard and Colia Lafayette setup Citizenship Schools, teaching people to pass literacy tests to get registered. A local SNCC Chapter made up primarily of high school students is established and the first mass meeting on voting rights is held at Tabernacle Baptist Church on May 14. OCT. 7, 1963 In what is later known as "Freedom Day," 350 Black people line up to register to vote at the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma. Registrars go as slowly as possible. Few manage to register, most are denied, but the protest is considered a huge victory by civil rights advocates. 1964 SNCC continues to organize in Selma; Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference arrive JULY 9, 1964 Dallas County Circuit Court Judge James Hare issues an injunction effectively forbidding gatherings of three or more people to discuss civil rights or voter registration. DEC. 28, 1964 King presents SCLC’s plan, the "Project for an Alabama Political Freedom Movement," conceived by James Bevel, which calls for mass action and voter registration attempts in Dallas County. 1965 Acceleration of the Selma Campaign JAN. 2, 1965 King begins his Selma campaign when an estimated 700 African Americans show up for a meeting at Brown Chapel in defiance of the injunction. -

Jimmie Lee Jackson Jimmie Lee Jackson

www.alafricanamerican.com 2016 PRESENTED BY Letter from the President Alabama is full of natural diversity — the Appalachian Mountains, the fertile Black Belt, and the white beaches along the gulf coast to name a few. However, it is our cultural diversity and how we learned to work together that has made Alabama great. As I write this letter, my thoughts are with our friends in South Carolina, who lovingly demonstrated how a diverse community can come together in a time of tragedy and, through their actions, inspire a nation. At AT&T, we understand the importance of diversity and the power of inclusion to bring about positive changes in communities. Every day we challenge ourselves and others to rethink possibilities and seize opportunities to create a more promising future. AT&T’s commitment to providing opportunities for all people is part of our core principles. Our 50-state workforce is 35 percent female and 41 percent people of color. Our managers are 37 percent female and 35 percent people of color. In 2014, we spent $16.5 billion with minority, women, and disabled veteran-owned business enterprises, representing 27% of our total expenditures. We believe that our success begins with a diverse and inclusive workforce that benefits our business, employees, customers, and communities. For the sixth year, we are pleased to highlight the achievements of African Americans who have contrib- Fred McCallum uted to Alabama’s rich heritage. A special thanks to all of our partners for their President, AT&T Alabama contributions and commitment to making the History Calendar a resource that encourages and inspires us all.