United Nations' Doublethink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol. XV, No. 41

2014 Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane H-Diplo Labrosse Roundtable and Web Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review h-diplo.org/roundtables Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Volume XV, No. 41 (2014) 14 July 2014 Introduction by Andy DeRoche Piero Gleijeses. Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria, and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. ISBN: 978- 1-4696-0968-3 (cloth, $40.00). Stable URL: http://h-diplo.org/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XV-41.pdf Contents Introduction by Andy DeRoche, Front Range Community College .......................................... 2 Review by Jamie Miller, Quinnipiac University ......................................................................... 7 Review by Sue Onslow, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, London .................................................................................................................................... 13 Review by Chris Saunders, University of Cape Town, South Africa ........................................ 20 Review by Elizabeth Schmidt, Loyola University Maryland .................................................... 24 Review by Alex Thomson, Coventry University ...................................................................... 26 Review by Anna-Mart van Wyk, Monash University, South Africa ........................................ 29 Author’s Response by Piero Gleijeses, Johns Hopkins University ......................................... -

DOUBLE THINK Originally Drawn in the 1960S in Yugoslavia As a Logo

,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, , , , DOUBLE THINK , , , , originally drawn in the , , , , 1960s in Yugoslavia as , , a logo for the shopfronts , , , , of the state-owned , , , , clothes company , , STANDARD KONFEKCIJA , , , , by Vinko Ozic-Pajic. , , NOW AVAILABLE IN , , , , medium & bold inline , , , ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, , DOUBLETHINK 1 MEDIUM 500PT 19 BOLD INLINE 500PT 84DOUBLETHINK 2 10PT The name Doublethink comes from the book 1984 by George Orwell. It means 'the power of holding two contradictory beliefs, simultaneously, in one’s mind and accepting both of them.' An appropriate name for a font prduced in a Communist regime. Medium 54PT A210PT e 36 82 50 19 43 f 72PT 48PT 2006 600PT 90PT DOUBLETHINK 3 THE SHOPS NO LONGER EXIST, HAVING ALL BEEN CLOSED AROUND 2001, AFTER THE FALL OF COMMUNISM. THERE ARE NOT MANY THAT HAVE MOURNED THE PASSING OF COMMUNISM, BUT VIRUS CAN'T HELP FEELING THAT A HUGE AMOUNT OF VALUABLE VISUAL CULTURE HAS BEEN THROWN AWAY ALONG WITH EVERY- THING ELSE. DOUBLETHINK 4 Bold Inline Bold 36 82 50 43 19 72PT 48PT 200690PT 720PT 72PT STANDARD KONFEKCIJA ITSELF STARTED OFF AS A MILITARY FABRIC COMPANY AND THEN BECAME THE FIRST FASHION BRAND IN COMMUNIST YUGOSLAVIA. IT IS FAMOUS FOR HAVING THE FIRST EVER PLASTIC CARRIER BAG IN THE COUNTRY AT THE TIME A MUCH COVETED ITEM. IT WAS ALSO HIGHLY UNUSUAL FOR ITS USE OF ORANGE AS ITS MAIN COLOUR, RATHER THAN THE OFFICIAL RED. K210PT n l11PT DOUBLETHINK 5 he power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one's mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them… To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, Tand then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies – all this is indispensably necessary. -

The Art of Communication in a Polarized World This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Art of Communication in a Polarized World

The Art of Communication in a Polarized World This page intentionally left blank The Art of Communication in a Polarized World KYLE CONWAY Copyright © 2020 Kyle Conway Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 https://doi.org/10.15215/aupress/9781771992930.01 Cover image © Suchat Nuchpleng / Shutterstock.com Cover design by Natalie Olsen Interior design by Sergiy Kozakov Printed and bound in Canada Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: The art of communication in a polarized world / Kyle Conway. Names: Conway, Kyle, 1977- author. Description: Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200162683 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200162691 ISBN 9781771992930 (softcover) | ISBN 9781771992947 (pdf) ISBN 9781771992954 (epub) | ISBN 9781771992961 (Kindle) Subjects: LCSH: Intercultural communication. | LCSH: Translating and interpreting. LCSH: Communication and culture. | LCSH: Language and culture. Classification: LCC P94.6 C66 2020 | DDC 303.48/2—dc23 This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) for our publishing activities and the assistance provided by the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Media Fund. This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons licence, Attribution–Noncommercial–No Derivative Works 4.0 International: see www.creativecommons.org. The text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given to the original author. To obtain permission for uses beyond those outlined in the Creative Commons licence, please contact AU Press, Athabasca University, at [email protected]. -

Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Introduction 1. I am grateful to Richard Boyd for his teaching and supervision, as a result of which I was introduced to the eminent importance, both within and outside philosophy, of arguments for naturalistic realism in Anglo- American analytic philosophy. See Boyd 1982, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1999, 2010. 2. This is how the term is spelled in Goodman 1973. Chapter 1 1. This took place at a talk at the University of Havana on the occasion of receiving an honorary degree December 8, 2001, Havana, Cuba. 2. Take, for example, Senel Paz saying, “I have always thought that it is the duty of the intellectuals . to examine closely all of our errors and negative tendencies, to study them with courage and without shame” (my translation) in Heras 1999: 148. 3. I have discussed this view at some length in Babbitt 1996. 4. Julia Sweig’s statement is significant given that she was director of Latin Ameri- can studies at the Council of Foreign Relations, a major foreign policy forum for the US government. See Sweig 2007, cited in Veltmeyer & Rushton 2013: 301. 5. “US Governor in First Trip to Castro’s Cuba” (1999, October 24), New York Times, p. 14, http:// search .proquest .com .proxy .queensu .ca /docview /110125370 / pageviewPDF ?accountid = 6180 [accessed March 10, 2013]. 6. The fact- value distinction emerged in European Enlightenment philosophy, originating, arguably, with Hume (1711– 1776) who argued that normative arguments (about value) cannot be derived logically from arguments about what exists. 7. The view that the mind, understood as consciousness, is physical, although distinctly so, is defended by philosophers of mind (Searle 1998; see also Prado 2006). -

Opening Adress of Bertrand Ramcharan, Acting United Nations

Opening Adress of Bertrand Ramcharan, Acting United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights At a Conference organized by the International Commission of Jurists Geneva, 23 October, 2003 The subject we have come here today to discuss is indeed an important and topical one: human rights, counter-terrorism, and international monitoring systems. I am pleased to be with you on this occasion and greet you warmly on behalf of all my colleagues in the Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights. Having been a Commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) before becoming a United Nations human rights Commissioner, you will understand my pleasure and gratitude, that this conference is being organized by the ICJ, with whom we have had a long and fruitful partnership for human rights going back for years. Some years ago, the ICJ did an important study on human rights and states of emergency and, more recently, it has done an important study on human rights and terrorism. The ICJ has thus made foundation contributions to the topics of interest to us today for which we are all grateful. I should like, in these opening remarks, to take each of the topics of our conference in turn: human rights, counter-terrorism, and international monitoring systems. First, human rights. What are the considerations that should be in our minds today as we commence this conference? It would be important, I believe, to remind ourselves of the international code of human rights that all Governments are pledged to live by. Can one say that the basic norms of international human rights law are in fact influencing all countries and that they are seeking in good faith to implement those norms? Many countries are indeed striving, in sometimes difficult circumstances, to follow the human rights path. -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

Digital Edition

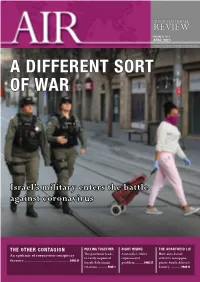

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

First Draft of the Paper Was Presented

Center for Liberal-Democratic Studies WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY REAL URBAN WAGE IN AN AGRICULTURAL ECONOMY WITHOUT LANDLESS FARMERS: SERBIA, 1862-1910 Boško Mijatović and Branko Milanović January 2019 1 January 2019 Real urban wage in an agricultural economy without landless farmers: Serbia, 1862-1910 Boško Mijatović and Branko Milanović1 1. Introduction During the past couple of decades an extensive work has been done on historical real wages. The objective was to assess living standards of the populations before national accounts became available. Since historical wage data are relatively abundant, it was thought that the best approach to study living standards of at least working population would be to collect wage data and contrast them to a basket of essential goods (whose prices as well would be collected). The idea was already present in Colin Clark’s Conditions of Economic Progress. It was more precisely defined by Henry Phelps-Brown and Sheila Hopkins (1962) and named “housewife’s shopping basket” and used by Braudel in The Perspective of the World (vol. 3 Civilization and Capitalism, p. 616) but has been expanded and developed in a number of papers by Robert Allen beginning with his 2001 article “The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War”.2 There and in the subsequent work Allen decided to look at wages for two types of laborers: a construction worker and an “ordinary” unskilled worker, and to use two baskets of goods: a “respectability basket” (the term having its origin in Adam Smith’s statement about the goods that every self-respecting person, at a given time and place, would expect to be able consume) and a much more austere the “bare-bones” or subsistence basket. -

British Fleet Fights Italians Off Corfu

Weather Forecast Cloudy and continued cool, lowest to- 'From Press to Home night about 46; tomorrow considerable cloudiness, slightly warmer. Tempera- Within the Hour' tures today—Highest, 50, at 2 p.m.; Most in lowest, 46, at 6 a.m. people Washington have The * Star delivered to their homes From the United States Weather Bureau report. every Full details on Pn*e A-2. evening and Sunday morning. Closing New York Markets, Page 16. (JP) Meant Attoeiated Pratt. 88th YEAR, No. 35,244. WASHINGTON, D. C., MONDAY, OCTOBER 28, 1940 — THIRTY-FOUR PAGES. *** THREE CENTS. BRITISH FLEET FIGHTS ITALIANS OFF CORFU Greeks Fascist and Churchill All Heir ---Invaders; Battling King♦.....—-- Pledge /TIT WOULDNtN f MAKE ANr DIFFERENCE \ Roosevelt Acts Turks Reported Entering Thrace; \^WHAT 1 SAID! L To 6 Alarms in Athens; Airports Hit Safeguard T U. S. Interests Yugoslavs and Positive English Phones Hull in Crisis; Metaxas Regime Declares Fear Assurances Sent Bulgars Crowds Turn Out in of War War After Flatly Rejecting Spread To New Ally and New York By the Associated Press. Jersey SOFIA, Bulgaria, Oct. 28 — By the Associated Press. By JOHN C. HENRY, Ultimatum From Rome Fears that a further of Oct. 28.—Both spreading LONDON, King Star Staff Correspondent. the war through Southeastern George VI and Prime Minister BROOKLYN, N. Oct. 28 — Europe might flame from Italian Y., Churchill have Greece BULLETIN invasion of Greece brought hur- promised Keeping in frequent telephonic con- ried conferences to- every help against the and the dis- LONDON, Oct. 28 (/P).—Reuters, British news government possible tact with Washington day in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, Italian invaders in personal mes- turbing Balkan crisis, President agency, reported tonight from Athens that Greek Greece's neighbors. -

Geneva, June 16Th, 2003 Bertrand Ramcharan Deputy High

Geneva, June 16th, 2003 Bertrand Ramcharan Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights United Nations Geneva, Switzerland RE: Human Rights and the World Summit on the Information Society Your Excellency Mr. Bertrand Ramcharan, The under-signed civil society organizations strongly encourage your active participation in the preparatory committee and summit meeting of the World Summit on the Information Society, taking place in September and December 2003, respectively. Human rights are an essential requirement of the Information Society, as elaborated in the draft declaration of the WSIS (WSIS/PCIP/DT/1-E): 10. The essential requirements for the development of an equitable Information Society include: The respect for all internationally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms. Notably the right to freedom of opinion and expression, including the right to hold opinions without interference and seek to, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers in accordance with article 19 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and to unhindered access by individuals to communication media and information sources… As the United Nations highest human rights official, your good offices are needed to ensure that human rights language in the WSIS process is comprehensive, strong and consistent with resolutions and decisions adopted by the Commission on Human Rights and build upon human rights language developed through the various UN world summits and conferences. Civil society organizations view ICTs as having both tremendous applications that enhance human rights, such as through the rapid dissemination of action alerts and instant access to human rights information, and disturbing capacities to greatly diminish human rights, such as by providing governments with means enabling intrusive surveillance and monitoring and therefore, repression. -

Nineteen Eighty-Four

MGiordano Lingua Inglese II Nineteen Eighty-Four Adapted from : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nineteen_Eighty-Four Nineteen Eighty-Four, sometimes published as 1984, is a dystopian novel by George Orwell published in 1949. The novel is set in Airstrip One (formerly known as Great Britain), a province of the superstate Oceania in a world of perpetual war, omnipresent government surveillance, and public manipulation, dictated by a political system euphemistically named English Socialism (or Ingsoc in the government's invented language, Newspeak) under the control of a privileged Inner Party elite that persecutes all individualism and independent thinking as "thoughtcrimes". The tyranny is epitomised by Big Brother, the quasi-divine Party leader who enjoys an intense cult of personality, but who may not even exist. The Party "seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power." The protagonist of the novel, Winston Smith, is a member of the Outer Party who works for the Ministry of Truth (or Minitrue), which is responsible for propaganda and historical revisionism. His job is to rewrite past newspaper articles so that the historical record always supports the current party line. Smith is a diligent and skillful worker, but he secretly hates the Party and dreams of rebellion against Big Brother. As literary political fiction and dystopian science-fiction, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a classic novel in content, plot, and style. Many of its terms and concepts, such as Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak, Room 101, Telescreen, 2 + 2 = 5, and memory hole, have entered everyday use since its publication in 1949. -

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document.