New Zealand and ASEAN: a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

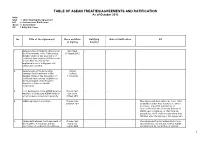

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: from Cold War to Conditionality

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality Lee Jones Abstract Despite their other theoretical differences, virtually all scholars of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agree that the organisation’s members share an almost religious commitment to the norm of non-intervention. This article disrupts this consensus, arguing that ASEAN repeatedly intervened in Cambodia’s internal political conflicts from 1979-1999, often with powerful and destructive effects. ASEAN’s role in maintaining Khmer Rouge occupancy of Cambodia’s UN seat, constructing a new coalition government-in-exile, manipulating Khmer refugee camps and informing the content of the Cambodian peace process will be explored, before turning to the ‘creeping conditionality’ for ASEAN membership imposed after the 1997 ‘coup’ in Phnom Penh. The article argues for an analysis recognising the political nature of intervention, and seeks to explain both the creation of non- intervention norms, and specific violations of them, as attempts by ASEAN elites to maintain their own illiberal, capitalist regimes against domestic and international political threats. Keywords ASEAN, Cambodia, Intervention, Norms, Non-Interference, Sovereignty Contact Information Lee Jones is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF, UK. His research focuses on ASEAN and intervention in Cambodia, East Timor, and Burma. Comments are welcomed. Email: [email protected]. Tel/Fax: (+44) (0)1865 28890. ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: -

The Role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Democracy Support

The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy support www.idea.int THE ROLE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS IN POST- CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND DEMOCRACY SUPPORT Julio S. Amador III and Joycee A. Teodoro © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit thepublication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic design by Turbo Design CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. ASEAN’S INSTITUTIONAL MANDATES ............................................................... 5 3. CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND THE ROLE OF ASEAN ...... 7 4. ADOPTING A POST-CONFLICT ROLE FOR -

Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 One Vision, One Identity, One Community Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, April 2009 352.1159 1. ASEAN – Summit – Blueprints 2. Political-Security – Economic – Socio-Cultural ISBN 978-602-8411-04-2 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2009 All rights reserved ii Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Table of Contents Cha-am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for the ASEAN Community (2009-2015) ..........................01 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint .........................................................................................05 ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint ....................................................................................................21 -

Warriors Walk Heritage Trail Wellington City Council

crematoriumchapel RANCE COLUMBARIUM WALL ROSEHAUGH AVENUE SE AFORTH TERRACE Wellington City Council Introduction Karori Cemetery Servicemen’s Section Karori Serviceman’s Cemetery was established in 1916 by the Wellington City Council, the fi rst and largest such cemetery to be established in New Zealand. Other local councils followed suit, setting aside specifi c areas so that each of the dead would be commemorated individually, the memorial would be permanent and uniform, and there would be no distinction made on the basis of military or civil rank, race or creed. Unlike other countries, interment is not restricted to those who died on active service but is open to all war veterans. First contingent leaving Karori for the South African War in 1899. (ATL F-0915-1/4-MNZ) 1 wellington’s warriors walk heritage trail Wellington City Council The Impact of Wars on New Zealand New Zealanders Killed in Action The fi rst major external confl ict in which New Zealand was South African War 1899–1902 230 involved was the South African War, when New Zealand forces World War I 1914–1918 18,166 fought alongside British troops in South Africa between 1899 and 1902. World War II 1939–1945 11,625 In the fi rst decades of the 20th century, the majority of New Zealanders Died in Operational New Zealand’s population of about one million was of British descent. They identifi ed themselves as Britons and spoke of Services Britain as the ‘Motherland’ or ‘Home’. Korean War 1950–1953 43 New Zealand sent an expeditionary force to the aid of the Malaya/Malaysia 1948–1966 20 ‘Mother Country’ at the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914. -

1 Battle Weariness and the 2Nd New Zealand Division During the Italian Campaign, 1943-45

‘As a matter of fact I’ve just about had enough’;1 Battle weariness and the 2nd New Zealand Division during the Italian Campaign, 1943-45. A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University New Zealand. Ian Clive Appleton 2015 1 Unknown private, 24 Battalion, 2nd New Zealand Division. Censorship summaries, DA 508/2 - DA 508/3, (ANZ), Censorship Report No 6/45, 4 Feb to 10 Feb 45, part 2, p.1. Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Abstract By the time that the 2nd New Zealand Division reached Italy in late 1943, many of the soldiers within it had been overseas since early 1941. Most had fought across North Africa during 1942/43 – some had even seen combat earlier, in Greece and Crete in 1941. The strain of combat was beginning to show, a fact recognised by the division’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg. Freyberg used the term ‘battle weary’ to describe both the division and the men within it on a number of occasions throughout 1944, suggesting at one stage the New Zealanders be withdrawn from operations completely. This study examines key factors that drove battle weariness within the division: issues around manpower, the operational difficulties faced by the division in Italy, the skill and tenacity of their German opponent, and the realities of modern combat. -

The New Zealand Soldier in World War II

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. lHE N[W ZEALAND SOLDIER IN WORLD WAR 11: ~YTH Mm nr fl[ 1 TY A thes i s presented in partial fulfilme~t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University John Reginald Mcleod 1 980 ·~t . .t_ R ll ABSTRACT Th e New Zua l and soldier has ga i ned a r eputation for be i ng an outstanding sol dier . Th e p roli fi c New Zea l a nd invol vement i n the nume r ous Wdrs of this century have allowed him to deve l op and consolidate this reputdtion . Wo rld Wdr I I was to add further lustre t o this reputulio11 , The que •,ti.011 th.it this pone c; i!; whethe r Lhe r ep u tcJtio11 is justified - how much is ~yth and how much is reality? In the early st~~es of World w~r II Lho New Zealander fai l ed to live up to his ~yLhica l reputation . The ba l es o f Greece and Crete , in pa r ticular , showed the totol l y unprofessiona l nature o f the New Zealand Army . Much of the weaknes s es shown in these battles were caused by i nadequate preparation . The Army had been on e o f t he principa l victims of the retrenchment policies of success i ve governme nts betwe en the w~ r s . -

The New Zealand Army Officer Corps, 1909-1945

1 A New Zealand Style of Military Leadership? Battalion and Regimental Combat Officers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces of the First and Second World Wars A thesis provided in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Wayne Stack 2014 2 Abstract This thesis examines the origins, selection process, training, promotion and general performance, at battalion and regimental level, of combat officers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces of the First and Second World Wars. These were easily the greatest armed conflicts in the country’s history. Through a prosopographical analysis of data obtained from personnel records and established databases, along with evidence from diaries, letters, biographies and interviews, comparisons are made not only between the experiences of those New Zealand officers who served in the Great War and those who served in the Second World War, but also with the officers of other British Empire forces. During both wars New Zealand soldiers were generally led by competent and capable combat officers at all levels of command, from leading a platoon or troop through to command of a whole battalion or regiment. What makes this so remarkable was that the majority of these officers were citizen-soldiers who had mostly volunteered or had been conscripted to serve overseas. With only limited training before embarking for war, most of them became efficient and effective combat leaders through experiencing battle. Not all reached the required standard and those who did not were replaced to ensure a high level of performance was maintained within the combat units. -

Institutional Racism and the Dynamics of Privilege in Public Health

Institutional Racism and the Dynamics of Privilege in Public Health A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management at The University of Waikato by HEATHER ANNE CAME _____________________________________ 2012 ABSTRACT Institutional racism, a pattern of differential access to material resources and power determined by race, advantages one sector of the population while disadvantaging another. Such racism is not only about conspicuous acts of violence but can be carried in the hold of mono-cultural perspectives. Overt state violation of principles contributes to the backdrop against which much less overt yet insidious violations occur. New Zealand health policy is one such mono- cultural domain. It is dominated by western bio-medical discourses that preclude and under-value Māori,1 the indigenous peoples of this land, in the conceptualisation, structure, content, and processes of health policies, despite Te Tiriti o Waitangi2 guarantees to protect Māori interests. Since the 1980s, the Department of Health has committed to honouring the Treaty of Waitangi as the founding document of Māori-settler relationships and governance arrangements. Subsequent Waitangi Tribunal reports, produced by an independent Commission of Inquiry have documented the often-illegal actions of successive governments advancing the interests of Pākehā3 at the expense of Māori. Institutional controls have not prevented inequities between Māori and non-Māori across a plethora of social and economic indicators. Activist scholars work to expose and transform perceived inequities. My research interest lies in how Crown Ministers and officials within the public health sector practice institutional racism and privilege and how it can be transformed. -

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence Editor Dr Claire Breen Editor: Dr Claire Breen Administrative Assistance: Janine Pickering The Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence is published annually by the University of Waikato School of Law. Subscription to the Yearbook costs $NZ35 (incl gst) per year in New Zealand and $US40 (including postage) overseas. Advertising space is available at a cost of $NZ200 for a full page and $NZ100 for a half page. Back numbers are available. Communications should be addressed to: The Editor Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence School of Law The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 New Zealand North American readers should obtain subscriptions directly from the North American agents: Gaunt Inc Gaunt Building 3011 Gulf Drive Holmes Beach, Florida 34217-2199 Telephone: 941-778-5211, Fax: 941-778-5252, Email: [email protected] This issue may be cited as (2008-2009) Vols 11-12 Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence. All rights reserved ©. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1994, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission of the publisher. ISSN No. 1174-4243 Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence Volumes 11 & 12 (combined) 2008 & 2009 Contents NEW ZEALAND’S FREE TRADE AGREEMENT WITH CHINA IN CONTEXT: DEMONSTRATING LEADERSHIP IN A GLOBALISED WORLD Hon Jim McLay CNZM QSO 1 CHINA TRANSFORMED: FTA, SOCIALISATION AND GLOBALISATION Yongjin Zhang 15 POLITICAL SPEECH AND SEDITION The Right Hon Sir Geoffrey Palmer 36 THE UNINVITED GUEST: THE ROLE OF THE MEDIA IN AN OPEN DEMOCRACY Karl du Fresne 52 TERRORISM, PROTEST AND THE LAW: IN A MARITIME CONTEXT Dr Ron Smith 61 RESPONDING TO THE ECONOMIC CRISIS: A QUESTION OF LAW, POLICY OR POLITICS Margaret Wilson 74 WHO DECIDES WHERE A DECEASED PERSON WILL BE BURIED – TAKAMORE REVISITED Nin Tomas 81 Editor’s Introduction This combined issue of the Yearbook arises out of public events that were organised by the School of Law (as it was then called) in 2008 and 2009.