The Diary of Sami Yengin, 1917-18: the End of Ottoman Rule in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case #2 United States of America (Respondent)

Model International Court of Justice (MICJ) Case #2 United States of America (Respondent) Relocation of the United States Embassy to Jerusalem (Palestine v. United States of America) Arkansas Model United Nations (AMUN) November 20-21, 2020 Teeter 1 Historical Context For years, there has been a consistent struggle between the State of Israel and the State of Palestine led by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 2018, United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. embassy located in Tel Aviv would be moving to the city of Jerusalem.1 Palestine, angered by the embassy moving, filed a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2018.2 The history of this case, U.S. relations with Israel and Palestine, current events, and why the ICJ should side with the United States will be covered in this research paper. Israel and Palestine have an interesting relationship between war and competition. In 1948, Israel captured the west side of Jerusalem, and the Palestinians captured the east side during the Arab-Israeli War. Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948. In 1949, the Lausanne Conference took place, and the UN came to the decision for “corpus separatum” which split Jerusalem into a Jewish zone and an Arab zone.3 At this time, the State of Israel decided that Jerusalem was its “eternal capital.”4 “Corpus separatum,” is a Latin term meaning “a city or region which is given a special legal and political status different from its environment, but which falls short of being sovereign, or an independent city-state.”5 1 Office of the President, 82 Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem § (2017). -

47 – Your Virtual Visit – 10 Lh Trophy

YOUR VIRTUAL VISIT - 47 TO THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY MUSEUM OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Throughout 2021, the Virtual Visit series will be continuing to present interesting features from the Museum’s collection and their background stories. The Australian Army Museum of Western Australia is now open four days per week, Wednesday through Friday plus Sunday. Current COVID19 protocols including contact tracing apply. 10 Light Horse Trophy Gun The Gun Is Captured The series of actions designated the Third Battle of Gaza was fought in late October -early November 1917 between British and Ottoman forces during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. The Battle came after the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) victory at the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October had ended the stalemate in Southern Palestine. The fighting marked the launch of Southern Palestine Offensive, By 10 November, the Gaza-to-Beersheba line had been broken and the Ottoman Army began to withdraw. The 10th Australian Light Horse Regiment was part of the pursuit force trying to cut off the retiring Ottomans. Advancing forces were stopped by a strong rear guard of Turkish, Austrian and German artillery, infantry and machine guns on a ridge of high ground south of Huj, a village 15 km north east of Gaza. The defensive position was overcome late on 8 November, at high cost, by a cavalry charge by the Worcestershire and Warwickshire Yeomanry. 1 Exploitation by the 10th Light Horse on 9 November captured several more artillery pieces which were marked “Captured by 10 LH” This particular gun, No 3120, K26, was captured by C Troop, commanded by Lt FJ MacGregor, MC of C Squadron. -

Palestine Vision of the Palestinian Lands Between 67/2012, the Palestinians Are Seeing That Olive Became a Tree

It all started with two promises: a Jewish National Home and a Arab State in Pala- estine by the British government during the World War I. “DON´T LET THE OLIVE BRANCH The British Mandate in Palaestina, who- se administration replaced the Otto- FALL FROM MY HAND”. of book the man Empire after World War I, found it the difficult to succeed in the beginning of When Yasser Arafat first went to speak at the United Nations General Assemby, he said that he the hostilities between Arabs and Jews came “bearing an olive branch in one hand and a freedom fighter´s gun in the other”, and conclu- in the 20´s and 30´s. ded: “don´t let the olive branch fall from my hand”. In order to find a viable solution to During the last decades, the olive branch lived together with the gun, at the same time. Sometimes the problem, it was agreed by the Peel the olive branch fell on the ground, sometimes does not. book Commission that there would be a di- In many situations described in this book, and especially since Oslo Accords and the Resolution palestine vision of the Palestinian lands between 67/2012, the palestinians are seeing that olive became a tree. the two peoples, with the creation of This book is dedicated to peace, not war. two sovereign States. England was so- There is one point that has to be acknowleged: in the Palestinian conflict there are no heroes or lely responsible for resolving the issues villains. For that sense, this book sought to demonstrate that these and other realities are part of in Palaestina during their administration of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict that originated during the British Mandate for territorial issues, on behalf of the League of Nations. -

United Nations Interagency Health-Needs-Assessment Mission

United Nations interagency health-needs-assessment mission Southern Turkey, 4−5 December 2012 IOM • OIM Joint Mission of WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM 1 United Nations interagency health-needs-assessment mission Southern Turkey, 4−5 December 2012 Joint Mission of WHO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF and IOM Abstract On 4–5 December 2012, a United Nations interagency health-needs-assessment mission was conducted in four of the 14 Syrian refugee camps in southern Turkey: two in the Gaziantep province (İslahiye and Nizip camps), and one each in the provinces of Kahramanmaraş (Central camp) and Osmaniye (Cevdetiye camp). The mission, which was organized jointly with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Ministry of Health of Turkey and the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency of the Prime Ministry of Turkey (AFAD), the United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for refugees (UNHCR) and comprised representatives of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). It was coordinated by WHO. The primary goals of the mission were: to gain a better understanding of the capacities existing in the camps, including the health services provided, and the functioning of the referral system; and, on the basis of the findings, identify how the United Nations agencies could contribute to supporting activities related to safeguarding the health of the more than 138 000 Syrian citizens living in Turkey at the time of the mission. The mission team found that the high-level Turkish health-care services were accessible to and free of charge for all Syrian refugees, independent of whether they were living in or outside the camps. -

Full Bibliography of Titles and Categories in One Handy PDF

Updated 21 June 2019 Full bibliography of titles and categories in one handy PDF. See also the reading list on Older Palestine History Nahla Abdo Captive Revolution : Palestinian Women’s Anti-Colonial Struggle within the Israeli Prison System (Pluto Press, 2014). Both a story of present detainees and the historical Socialist struggle throughout the region. Women in Israel : Race, Gender and Citizenship (Zed Books, 2011) Women and Poverty in the OPT (? – 2007) Nahla Abdo-Zubi, Heather Montgomery & Ronit Lentin Women and the Politics of Military Confrontation : Palestinian and Israeli Gendered Narratives of Diclocation (New York City : Berghahn Books, 2002) Nahla Abdo, Rita Giacaman, Eileen Kuttab & Valentine M. Moghadam Gender and Development (Birzeit University Women’s Studies Department, 1995) Stéphanie Latte Abdallah (French Institute of the Near East) & Cédric Parizot (Aix-Marseille University), editors Israelis and Palestinians in the Shadows of the Wall : Spaces of Separation and Occupation (Ashgate, 2015) – originally published in French, Paris : MMSH, 2011. Contents : Shira Havkin : Geographies of Occupation – Outsourcing the checkpoints – when military occupation encounters neoliberalism / Stéphanie Latte Abdallah : Denial of borders: the Prison Web and the management of Palestinian political prisoners after the Oslo Accords (1993-2013) / Emilio Dabed : Constitutionalism in colonial context – the Palestinian basic law as a metaphoric representation of Palestinian politics (1993-2007) / Ariel Handel : What are we talking about when -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Download Download

British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2021 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 19 March 2021 Citation: Roslyn Shepherd King Pike, ‘What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918’, British Journal for Military History, 7.1 (2021), pp. 87-112. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of IDENTIFYING MILITARY ENGAGEMENTS IN EGYPT & THE LEVANT 1915-1918 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915- 1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike* Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the official names listed in the 'Egypt and Palestine' section of the 1922 report by the British Army’s Battles Nomenclature Committee and compares them with descriptions of military engagements in the Official History to establish if they clearly identify the events. The Committee’s application of their own definitions and guidelines during the process of naming these conflicts is evaluated together with examples of more recent usages in selected secondary sources. The articles concludes that the Committee’s failure to accurately identify the events of this campaign have had a negative impacted on subsequent historiography. Introduction While the perennial rose would still smell the same if called a lily, any discussion of military engagements relies on accurate and generally agreed on enduring names, so historians, veterans, and the wider community, can talk with some degree of confidence about particular events, and they can be meaningfully written into history. -

Militia Politics

INTRODUCTION Humboldt – Universität zu Berlin Dissertation MILITIA POLITICS THE FORMATION AND ORGANISATION OF IRREGULAR ARMED FORCES IN SUDAN (1985-2001) AND LEBANON (1975-1991) Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil) Philosophische Fakultät III der Humbold – Universität zu Berlin (M.A. B.A.) Jago Salmon; 9 Juli 1978; Canberra, Australia Dekan: Prof. Dr. Gert-Joachim Glaeßner Gutachter: 1. Dr. Klaus Schlichte 2. Prof. Joel Migdal Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.07.2006 INTRODUCTION You have to know that there are two kinds of captain praised. One is those who have done great things with an army ordered by its own natural discipline, as were the greater part of Roman citizens and others who have guided armies. These have had no other trouble than to keep them good and see to guiding them securely. The other is those who not only have had to overcome the enemy, but, before they arrive at that, have been necessitated to make their army good and well ordered. These without doubt merit much more praise… Niccolò Machiavelli, The Art of War (2003, 161) INTRODUCTION Abstract This thesis provides an analysis of the organizational politics of state supporting armed groups, and demonstrates how group cohesion and institutionalization impact on the patterns of violence witnessed within civil wars. Using an historical comparative method, strategies of leadership control are examined in the processes of organizational evolution of the Popular Defence Forces, an Islamist Nationalist militia, and the allied Lebanese Forces, a Christian Nationalist militia. The first group was a centrally coordinated network of irregular forces which fielded ill-disciplined and semi-autonomous military units, and was responsible for severe war crimes. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

United Nations A/HRC/23/NGO/1

United Nations A/HRC/23/NGO/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 14 May 2013 English only Human Rights Council Twenty-third session Agenda item 7 Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Written statement* submitted by the Mouvement contre le Racisme et pour l’Amitié entre les Peuples (MRAP), a non- governmental organization on the roster The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [19 April 2013] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non-governmental organization(s). GE.13-13576 A/HRC/23/NGO/1 Final Session of the Russell Tribunal on Palestine: time for accountability On 16th and 17th March 2013, the Russell Tribunal on Palestine held its final session in Brussels1 in order to summarize the violations of international law by State of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territories as well as the responsibility of the international community and the private sector in assisting the State of Israel in its violations of international law. I. The particular violations of international law committed by Israel As noted by the Tribunal at its previous sessions, well documented acts committed by Israel constitute violations of the basic rules of international law2: • violation of the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination codified in resolutions 1514 (XV) and 2625 (XXV); • in relation to the construction of the wall, as stated at Paragraph -

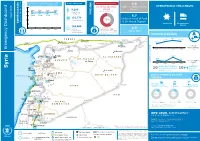

Syria External Dashboard April 2016 -Draft for May 19

3.89 million people assisted in April OTHER PROGRAMMES NET FUNDING REQUIREMENTS* 4.8 through General Food Distributions OPERATIONAL CHALLENGES Assisted 5 Emergency Operation million refugees in the 200339 4.0m 4.0m 4.0m 4.0m 8,200 Region MAY-OCTOBER 2016 4 Pregnant and Targeted 3.89m lactating women FUNDING 3 3.65m 3.79m 3.71m 8.7 April 2016 135,779 million in need of Food 2 Children-Nutrition 70% Emergency Operation 200339 Emergency Operation & Livelihood Support BENEFICIARIES 1 Insecurity Humanitarian 160,000 Access 0 Net Funding 6.5 JAN FEB MAR APR students Requirements: 230m Total Requirements: 331m million IDPs Snack Programme *does not include pledges made at the London Conference Source: WFP,12 May 2016 COMMON SERVICES Cizre- 7,100 T U R K E Y g! 6,071 Sanliurfa Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al 5,809 ! Darbasiyah Qamishli ! Peshkabour Gaziantep Ayn al 3,870 Adana ! Ceylanpinar-Ras g! !! g! ! Arab dg" Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus Al Ayn g! Akcakale-Tall Qamishly Al Yaroubiya R CARGO "! g! Bab As ! Abiad g! Qamishli * - Rabiaa ! d g g! TE c *Salama Cobanbey TRANSPORTED Emergency Dashboard Dashboard Emergency 3 Mercin ! g! JAN FEB MAR APR (m ) ! ! g!! g LUS !! Manbij ! !Al-Hasakeh C ! ! Reyhanli! - S * ! C !!Bab !al Hawa I 1,700 ! ! !! T !Antioch !!! ! !!!!!Aleppo g! !!!!!! !!!!!!!! A L - H A S A K E H S !!!!!!!!! ! ! I !! !! ! 929 Karbeyaz !!! A R - R A Q Q A 840 Yayladagi ! !! OG 648 ! Id!leb! A L E P P O ! L RELIEF GOODS g! ! Ar-Raqqa g! !!!! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! STORED ! !! ! !! !!!!! JAN FEB MAR APR (m3) !!I D L E!!B!! ! !!!!!!! !!! !!!! -

Türkiye'de Turizm Ulaştirmasi 21

TÜRKİYE’DE TURİZM ULAŞTIRMASI (Tourism Transportation in Turkey) Dr. SUNA DOĞANER* ÖZET: Ulaşım seyehati mümkün kılar ve bu sebepten turizmin önemli bir parça sıdır. Ulaşım herşeyden önce turizmin gelişiminin sebebi ve sonucudur: Ula şım sistemlerinin gelişimi turizmi canlandırır, turizmin yayılması da ulaşımı geliştirir. Karayolu ulaşımı, Türkiye’de pekçok sayfiyenin, tarihi ve kültürel merkezin doğması ve gelişmesinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. Türkiye’de pek çok şehire hava ulaşımının sağlanması uzak yerlere ulaşımı kolaylaştırmıştır. Organize turların gelişmesi aynı zamanda hava ulaşımını canlandırmıştır. De nizde seyehat oldukça zevklidir ve gemi seyehatlerine olan ilgi artmaktadır. Uluslararası hatlarda feribot seferleri Adriyatik (İzmir-Venedik ve Antalya- Venedik arasında) ve Kıbrıs hatlarında yapılmaktadır ayrıca iç hatlarda feri bot seferleri vardır. Buharlı Tren Turları Türkiye’de demiryolu ile seyehatin gelişmesinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. Sonuç olarak Türkiye’de ulaşım iç ve dış turizmde önemli bir rol oynamaktadır. ABSTRACT: Transport, which makes travel possible, is therefore an integral part of to urism. Transport has been at once a cause an effect of the growth of tourism: improved transport facilities have stimulated tourism, the expansion of tou- ırsm has stimulated transport. Road transport has been a very important fac tor affecting the rise and growth of many seaside resorts, historic and cultural centers in Turkey. The inception of air transport to many cities made easy long distance transport posible in Turkey. The development of package tours has also stimulated air transport. Sea travel is in itself a pleasure and cruising ho lidays have grown in importance. Ferry -boat cruises on international lines are Adriatic (between İzmir-Venice and Antalya-venice) and Cyprus services.