Dancing in Music Videos, Or How I Learned to Dance Like Janet... Miss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

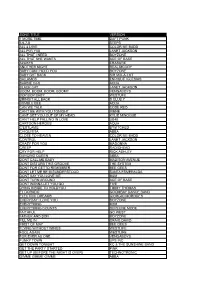

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

RHYTHM NATION PAGE 1 of 2

RHYTHM NATION PAGE 1 of 2 Description: Students will explore similarities and differences between cultures through music and dance. Learning Objectives: • Students will learn to recognize music and instruments of another culture. • Students will demonstrate rhythm through expressive movements. Activity Time: 20–30 minutes Materials: • CD player • Music from other cultures • Dance instructions Directions: Set Up: • Review your curriculum and research the music, instruments and dance of a culture the class is studying. Locate a CD with music from that culture. To research dance information, log on to the teacher section of the American Folklore Center on the Library of Congress Web site at www.loc.gov or check the Web sites listed in the library of the Folk Dance Association’s site at www.folkdancing.org. Day of the Activity: • Begin a class discussion by asking students what kind of music they listen to, what kind of instruments are used in this music and why they like that particular kind of music. • Have students demonstrate how they move to the music they listen to. • Play a CD with music from the culture you are studying, and ask students what group of people this music represents and what kind of instruments they hear. • Demonstrate traditional dance steps to the music. • Have students join in the dance, performing the traditional dance steps and creating their own. Note: Could be team-taught with physical education teacher. Submitted by Kathy Strunk, Robbins Elementary, Robbins,Tennessee The National Football League and the American Heart Association are proud to work together to produce What Moves U. -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 1980'S

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 1980’s 1. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson 2. Into the Groove - Madonna 3. Super Freak Part I - Rick James 4. Beat It - Michael Jackson 5. Funkytown - Lipps Inc. 6. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) - Eurythmics 7. Don't You Want Me? - Human League 8. Tainted Love - Soft Cell 9. Like a Virgin - Madonna 10. Blue Monday - New Order 11. When Doves Cry - Prince 12. What I Like About You - The Romantics 13. Push It - Salt N Pepa 14. Celebration - Kool and The Gang 15. Flashdance...What a Feeling - Irene Cara 16. It's Raining Men - The Weather Girls 17. Holiday - Madonna 18. Thriller - Michael Jackson 19. Bad - Michael Jackson 20. 1999 - Prince 21. The Way You Make Me Feel - Michael Jackson 22. I'm So Excited - The Pointer Sisters 23. Electric Slide - Marcia Griffiths 24. Mony Mony - Billy Idol 25. I'm Coming Out - Diana Ross 26. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun - Cyndi Lauper 27. Take Your Time (Do It Right) - The S.O.S. Band 28. Let the Music Play - Shannon 29. Pump Up the Jam - Technotronic feat. Felly 30. Planet Rock - Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force 31. Jump (For My Love) - The Pointer Sisters 32. Fame (I Want To Live Forever) - Irene Cara 33. Let's Groove - Earth, Wind, and Fire 34. It Takes Two (To Make a Thing Go Right) - Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock 35. Pump Up the Volume - M/A/R/R/S 36. I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) - Whitney Houston 37. -

LN PR Template

JANET JACKSON ANNOUNCES 2ND NORTH AMERICAN LEG TO "UNBREAKABLE WORLD TOUR" - Due To Overwhelming Fan Demand, 27 New Cities Added - –Tickets For 2nd Leg Of Tour On Sale Starting July 20 at JanetJackson.com – LOS ANGELES (July 13, 2015) – Janet's Jackson's tour is not only UNBREAKABLE, it is now unstoppable thanks to her fans across North America. The recent BET Awards’ Ultimate Icon honoree, multiple GRAMMY® Award-winner and multi-platinum selling artist announced a 2nd North American leg to her UNBREAKABLE WORLD TOUR with an additional 27 new cities added to what has become one of the most highly-anticipated international tours. Janet has been listening to her fans and their overwhelming response to both her new music and her tour. They've asked her to bring the UNBREAKABLE WORLD TOUR to their city and now she's giving even more fans a chance to be part of this year's most exciting tour. The 2nd leg of the North American tour will kick off on January 12, 2016 in Portland, OR and will visit 27 cities including dates in New York City, Washington DC, Boston, Houston, Dallas, Philadelphia and more! A full list of dates on the 2nd leg of the UNBREAKABLE WORLD TOUR is below. All dates on the tour are being co-produced by Miss Jackson’s Rhythm Nation. Additional worldwide concerts will be announced at a later date. Fans who pre-order the album on JanetJackson.com will receive presale access for premium seating beginning July 14 at 10:00 a.m. until July 19 at 10:00 p.m. -

Woodbridge, Va Competition Results Standing Ovation O!Ward Sponsored By

WOODBRIDGE, VA COMPETITION RESULTS STANDING OVATION O!WARD SPONSORED BY: “PUT IT IN A LOVE SONG” C-UNIT STUDIO “RIVER DEEP” STRICTLY RHYTHM BRAVO! HIGH POINT O!WARD (Highest Scoring Group Routine of the Entire Weekend) “BOTTOM OF THE RIVER” STRICTLY RHYTHM NEXSTAR OUTSTANDING PERFORMANCE O!WARD SPONSORED BY: “YOUNG AND BEAUTIFUL” X SQUAD DANCERS “KIKI” STRICTLY RHYTHM WOODBRIDGE, VA COMPETITION RESULTS O!VERTURE ENTERTAINMENT AWARD “DOUBLE DUTCH BUS” CLARISSA’S SCHOOL OF PERFORMING ARTS ENCORE! ENTERTAINMENT AWARD “PROUD RIVER” X SQUAD DANCERS “MR. ROBOTO” CLARISSA’S SCHOOL OF PERFORMING ARTS BRAVO! ENTERTAINMENT AWARD “SPACE IS THE PLACE” STRICTLY RHYTHM “STUFF LIKE THAT THERE” STRICTLY RHYTHM WOODBRIDGE, VA COMPETITION RESULTS TITLE WINNER Petitie Miss BravO! Naomi Galotto “A Dream Is a Wish” Strictly Rhythm Little Mr BravO! Zak Sajjad “Come Together” Strictly Rhythm Junior Miss BravO! Isabelle Flugrad “Use Somebody” Strictly Rhythm Teen Miss BravO! Daniella Guarin “Youth” Strictly Rhythm Runner Up-Teen Miss BravO! Heather Spears “The Raven” Strictly Rhythm Miss BravO! Kathryne Rinaldo “Speaking in Tongues” Strictly Rhythm EXCELLENCE IN SHOWMANSHIP ZAK SAJJAD “COME TOGETHER” STRICTLY RHYTHM SOPHIE SULESKY “HERE WE GO NOW” VALLEY DANCE THEATRE CHELSEA KOLACZ “BEST OF ME” X SQUAD DANCERS PAIGE HORNBARRIER “OLD SKIN” VALLEY DANCE THEATRE EXCELLENCE IN TECHNIQUE SOLEIL KIRKLAND “LOVE YOU” STRICTLY RHYTHM ISABELLE FLUGRAD “USE SOMEBODY” STRICTLY RHYTHM HEATHER SPEARS “THE RAVEN” STRICTLY RHYTHM FRANTZ AUGUSTIN “TAKE A LOOK AT ME NOW” STRICTLY -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

¬タᆰmichael Jackson Mtv Awards 1995 Full

Rafael Ahmed Shared on Google+ · 1 year ago 1080p HD Remastered. Best version on YouTube Reply · 415 Hide replies ramy ninio 1 year ago Il est vraiment très fort Michael Jackson !!! Reply · Angelo Oducado 1 year ago When you make videos like this I recommend you leave the aspect ratio to 4:3 or maybe add effects to the black bars Reply · Yehya Jackson 11 months ago Hello My Friend. Please Upload To Your Youtube Channel Michael Jackson's This Is It Full Movie DVD Version And Dangerous World Tour (Live In Bucharest 1992). Reply · Moonwalker Holly 11 months ago Hello and thanks for sharing this :). I put it into my favs. Every other video that I've found of this performance is really blurry. The quality on this is really good. I love it. Reply · Jarvis Hardy 11 months ago Thank cause everyother 15 mn version is fucked damn mike was a bad motherfucker Reply · 6 Moonwalker Holly 11 months ago +Jarvis Hardy I like him bad. He's my naughty boy ;) Reply · 1 Nathan Peneha A.K.A Thepenjoker 11 months ago DopeSweet as Reply · vaibhav yadav 9 months ago I want to download michael jackson bucharest concert in HD. Please tell the source. Reply · L. Kooll 9 months ago buy it lol, its always better to have the original stuff like me, I have the original bucharest concert in DVD Reply · 1 vaibhav yadav 9 months ago +L. Kooll yes you are right. I should buy one. Reply · 1 L. Kooll 9 months ago +vaibhav yadav :) do it, you will see you wont regret it. -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

A Mass of Resurrection in Loving Memory Of

A Mass of Resurrection In Loving Memory Professional Services Entrusted to: Bell Funeral Home of Forestdale, Alabama Frank Phillip “Phil” Slovensky Internment Phillip was buried April 4, 2020 Saint Michael’s Cemetery Brookside, Alabama Pallbearers Phillip was buried April 4, 2020 and his Pallbearers were: Chris Hand Jaimie Hand Jerome Hand John Maxwell Patrick Maxwell Mark Slovensky Jimmy Slovensky Ron Slovensky Ryan Slovensky From the Family We mourn Phil’s passing because we are human and we will miss him dearly, but we rejoice because he lived a life of loving and generous service and he believed in Jesus’ promise of eternal life. We, the family of Frank Phillip Phil Slovensky., wish to extend our sincere gratitude and heartfelt appreciation for the many acts of kindness shown during this special and difficult time. We will remember forever your cards, calls, prayers, and your presence. The Slovensky Family 11:00 AM Saturday, August 8, 2020 Saint Patrick Catholic Church Adamsville, Alabama Very Reverend Vernon F. Huguley Pastor Phil Slovensky In Memory of Our Brother Phillip So much sorrow, with infinite pain, I little knew that morning God was to call my name. The emotions inside, we could never explain. In life I loved you dearly, in death I do the same. Our brother has left, as we stand here and cry. It broke my heart to leave you, I did not go alone. Our burning tears, are asking us why. For part of you went with me. The day God called me home. We'll cherish those memories, we all have shared. -

Stallworth Works on Stalling Airport Takeover

www.mississippilink.com VOL. 22, NO. 27 APRIL 28 - MAY 4, 2016 50¢ Stallworth works on stalling airport takeover By Othor Cain Early this month, allege is a “hostile takeover” of Jack- state to take my land without providing member makeup, giving the mayor of Contributing Writer Stallworth took to son’s Medgar Wiley Evers Internation- any type of compensation,” Stallworth Jackson and the city council one ap- Bishop Jeffrey Stallworth is no the courts again, this al Airport. said. “This is wrong and should not be pointment each. The governor would stranger to the court system. time in federal court. Stallworth, a former commissioner allowed to happen.” have two appointments while the lieu- In years past, Stallworth, pastor of He’s suing Gov. Phil of the airport says if this law goes into Stallworth is challenging HB 2162, tenant governor, the Mississippi De- Jackson’s non-denominational Word Bryant, the state of effect it will cause irreparable harm and which allows the state to take control velopment Authority, adjutant general, and Worship Church has been engulfed Stallworth Mississippi, the Mis- damage to him, residents of Jackson of the airport, abolish its current five- Rankin and Madison counties would with legal matters both personally and sissippi Legislature, East Metro Park- and the city at large. member board, all of whom are ap- each have one appointment. professionally. Some of those matters way and the Mississippi Department of “I’m a business owner. I own land in pointed by the mayor of Jackson. The are still pending. Transportation, for what he and others Jackson. -

Songs by Title

Sound Master Entertainment Songs by Title smedenver.com Title Artist Title Artist #thatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 1994 Jason Aldean (Come On Ride) The Train Quad City DJ's 1999 Prince (Everything I Do) I Do It For Bryan Adams 1st Of Tha Month Bone Thugs-N-Harmony You 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Bryan Adams 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer (Four) 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2 Step Unk & Timbaland Unk (Get Up I Feel Like Being A) James Brown 2.Oh Golf Boys Sex Machine 21 Guns Green Day (God Must Have Spent) A N Sync 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Little More Time On You 22 Taylor Swift N Sync 23 Mike Will Made-It & Miley (Hot St) Country Grammar Nelly Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew 23 (Exp) Mike Will Made-It & Miley (I Wanna Take) Forever Peter Cetera & Crystal Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J Tonight Bernard 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago (I've Had) The Time Of My Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes 3 Britney Spears Life Britney Spears (Oh) Pretty Woman Van Halen 3 A.M. Matchbox Twenty (One) #1 Nelly 3 A.M. Eternal KLF (Rock) Superstar Cypress Hill 3 Way (Exp) Lonely Island & Justin (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake KC & The Sunshine Band Timberlake & Lady Gaga Your Booty 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake (She's) Sexy + 17 Stray Cats & Timbaland (There's Gotta Be) More To Stacie Orrico 4 My People Missy Elliott Life 4 Seasons Of Loneliness Boyz II Men (They Long To Be) Close To Carpenters You 5 O'Clock T-Pain Carpenters 5 1 5 0 Dierks Bentley (This Ain't) No Thinkin Thing Trace Adkins 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train (You Can Still) Rock In Night Ranger 50's 2 Step Disco Break Party Break America 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 6th Avenue Heartache Wallflowers (You Want To) Make A Bon Jovi 7 Prince & The New Power Memory Generation 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 8 Days Of Christmas Destiny's Child Jay-Z & Beyonce 80's Flashback Mix (John Cha Various 1 Thing Amerie Mix)) 1, 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 9 P.M.