Dissolution Or Disillusion: the Unravelling of Civil Partnerships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 Cover April12.Indd

WWW.OUTMAG.CO.UK ISSUE SIXTY-FOUR 04/12 £FREE INSIDE PORTUGAL PARTYING LOS ANGELES PRIDE MADONNA’S MDNA MYRA DUBOIS Help! My man wants to open up our relationship Perfume Genius MIKE HADREAS: BOY N’ THE HOOD OUT IN THE CITY APRIL 2012 THE TEAM Hudson’s Editor DAVID HUDSON Letter [email protected] +44 (0)20 7258 1943 Design Concept Boutique Marketing www.boutiquemarketing.co.uk Graphic Designer Ryan Beal Sub Editor Chance Delgado Contributors Richard Phillips, Steven 10 Sparling, Soren Stauffer- Kruse, Josh Winning Photographer Chris Jepson Publishers CONTENTS It has been impossible to escape the news that the Sarah Garrett coalition Government intends to introduce full 04 LETTERS Linda Riley marriage equality for same-sex couples, proposing Send your Director of Advertising to allow them to hold civil marriage ceremonies on correspondence to & Exhibition Sales secular premises. editorial@outmag. Square Peg Media Despite the fact that the Government is not co.uk James McFadzean proposing to make it compulsory that any religious [email protected] group hold such ceremonies on their premises, the 06 MY LONDON + 44 (0)20 7258 1777 Catholic Church has been particularly outspoken on Rising cabaret star + 44 (0)7772 084 906 the subject. Scotland’s Cardinal Keith O’Brien Myra Dubois gives us Head of Business described the plans as “grotesque”, while the her capital highlights Development Archbishops of Westminster and Southwark jointly Lyndsey Porter wrote a public letter saying that it was the “duty” of 10 PERFUME [email protected] all Catholics to oppose such plans: “A change in the GENIUS PHOTO © CHRIS JEPSON39 + 44 (0)20 7258 1777 law would gradually and inevitably transform Seattle-based singer albums by Madonna, 42 OUTNEWS Advertising Manager society’s understanding of the purpose of marriage. -

Summer Reading Challenge 2020

Join the Silly Squad and the Let's Get Silly Ambassadors for an afternoon (ending with a bedtime story) of family fun! The Summer Reading Challenge 2020 will launch on Friday 5 June and you can join the Silly Squad on a new adventure by setting your own personal reading challenge to complete this summer. Create a free profile to keep track of your books, reviews, and all of the special rewards you unlock along the way. You'll also find heaps of super silly activities, quizzes, videos, games and more to keep you entertained at home. This year's Challenge runs from June to September, so there is plenty of time to take part and get silly this summer. Join us on Facebook on Friday 5 June to meet our super silly Ambassadors, who will be sharing their favourite silly stories, leading a draw-along to create your very own Silly Squad character, showing us their silliest dance moves, telling their most hilarious joke and sharing so much more silly fun with us all. Once you have celebrated with the Silly Squad at the Launch Party head on over to sillysquad.org.uk to start your seriously silly summer reading Challenge! Let's Get Silly Launch Party Schedule 4.00pm - Sam & Mark (as seen on CBBC) launch the Summer Reading Challenge 2020 and introduce you to the Silly Squad - telling you how you can sign up and start your seriously silly summer 4.10pm - Comedian, author and presenter, David Baddiel, reads from his children's book The Taylor TurboChaser 4:15pm - Author Gareth P Jones reads from his book Dinosaur Detective: Catnapped! and takes us on -

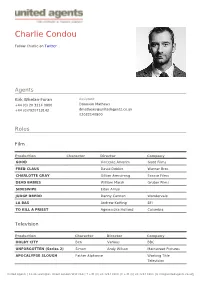

Charlie Condou

Charlie Condou Follow Charlie on Twitter Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company GOOD Vincente Amorim Good Films FRED CLAUS David Dobkin Warner Bros CHARLOTTE GRAY Gillian Armstrong Ecosse Films DEAD BABIES William Marsh Gruber Films SIDESWIPE Eitan Arrusi JUDGE DREDD Danny Cannon Wondervale LA BAS Andrew Kotting BFI TO KILL A PRIEST Agniesszka Holland Columbia Television Production Character Director Company HOLBY CITY Ben Various BBC UNFORGOTTEN (Series 2) Simon Andy Wilson Mainstreet Pictures APOCALYPSE SLOUGH Father Alphonse Working Title Television United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company CORONATION STREET Regular Various ITV THE IMPRESSIONISTS Tim Dunn & Mary BBC Downes SECRET SMILE Chris Menaul Granada MIDSOMER MURDERS Sarah Hellings Bentley Productions NATHAN BARLEY Chris Morris Hat Trick TRUST Philippa Langdale BBC THE NOBLE AND SILVER SHOW Gary Reich E4 HG WELLS Robert Young Hallmark URBAN GOTHIC Omar Madha Channel 5 PEAK PRACTICE Ken Grieve Carlton GIMME, GIMME, GIMME Liddy Oldroyd Tiger Aspect HONKEY SAUSAGES John McFarlane Radical Media ARMSTRONG & MILLER Matt Lipsey Channel 4 THE BILL Chris Lovett Thames TV PIE IN THE SKY Danny Hiller Select TV MARTIN CHUZZLEWIT Pedr James BBC CASUALTY Alan Waring BBC RIDES Andrew MacDonald Central THE STORY TELLER Paul Weiland TVS Films EVERY BREATH YOU TAKE Paul Seed Granada Stage Production Character Director Company THE CRUCIBLE Rev. Hale Douglas Rintoul Sell A Door NEXT FALL Luke Sheppard Southwark Playhouse DYING FOR IT Anna Mackmin The Almedia THE CHANGELING Dawn Walton Southwark Playhouse SHOPPING & F***ING Max Stafford-Clark No 1. -

Fatherhood Institute Annual Report 2012-13

Fatherhood Institute Annual Report 2012-13 www.fatherhoodinstitute.org Pushing fatherhood up the agenda Annual Report 2012-13 When I see my children at the weekend “ they say, ‘We don't want to go to McDonald's - can we read stories instead?’ “ Fathers Reading Every Day participant, Lambeth 1 Fatherhood Institute Annual Report 2012-13 2 www.fatherhoodinstitute.org Contents • Chief executives’ report 4 • About the Fatherhood Institute 6 • Our projects in 2012-13 9 • Our training and consultancy 14 • Policy, research and communications 16 • Governance, staff and funders 18 • Summarised financial statements 19 3 Fatherhood Institute Annual Report 2012-13 Chief executives' report Times are changing The UK still has a culture which places an unassailable value on motherhood. But times are changing. It’s not the 1950s any more. We live longer and have smaller families; women’s education and workplace achievements progress apace; men’s attitudes have shifted, and continue to do so. Today’s new mothers now spend only a tiny proportion of their lives pregnant or breastfeeding. It’s no longer necessary Fathers and the zeitgeist for them to tend exclusively to children and - given the The government has identified the zeitgeist of positive financial pressure we’re all under, and the dramatic decline in attitudes towards involved fatherhood and is tapping into it: the ‘male wage’ in lower and middle income families ministerial ‘spin’ on policies relating to families often highlights especially – leaving women ‘holding the baby’ is not even supporting fathers to be engaged parents – even when the economically practical any more. For families to escape actual policy barely does this. -

“ I Know What My HIV Status Is. So Should You. Get Tested.” World AIDS Dayy Special

clubs | bars | cabaret | life /0tNOVEMBERQXMAGAZINE.COM Suitable only for persons years of 18 and over. Darius Ferdynand says “ I know what my HIV status is. So should you. Get tested.” World AIDS Dayy Special print + web iPad + iPhone QX_977_Cover.indd 1 26/11/2013 19:56 Remember, Remember, 1st of December With HIV/AIDS still affecting so many gay men in the world today, and the spread of new infections rising, World AIDS Day remains one of our community’s most important events. It’s a time to remember the lives lost, the battles won and to better inform ourselves of the gay scene’s most prevalent health issue. And most of all, GET TESTED! Darius Knows His Status, So Should You One of the fittest gay porn stars around and this week’s QX cover star, Darius Ferdynand, has spoken out for World AIDS Day. In a YouTube video for Positive East he says: “I have great sex, but I do so SOLDIER ON FOR A knowing what my HIV status is. HEALTHIER COMMUNITY So should you.” It echoes the …And it’s not just porn stars like Darius message of most HIV charities Ferdynand that care about their sexual that it is always best to know health, James Wharton, a former Lance your status, for your own health Corporal with the Blues and Royals, took and that of others. You can view a rapid HIV test to encourage more gay the clip here: men to test for the virus. He said: “Modern www.positiveeast.org.uk tests are done in minutes, and you get your Check out result there and then. -

Collaborative Co-Parenting

COLLABORATIVE CO-PARENTING: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE LEGAL RESPONSE TO POLY- PARENTING IN CANADA AND THE UK Submitted by Philip Dennis Bremner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law, October 2015. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis, which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ……………………………………………………………………………… Abstract This socio-legal thesis explores the highly topical and underexplored issue of the legal regulation of gay and lesbian collaborative co-parenting in England & Wales, drawing on British Columbia (Canada) as a jurisdiction where this issue has been considered in more detail. These families involve reproductive collaborations between single or partnered lesbians and gay men where a child is conceived through assisted reproduction and each of the adults remain involved in the child’s life. Collaborative co-parenting can take a variety of forms, each of which is distinguishable from gamete donation or surrogacy because each of the adults continues to exercise some sort of parental role in relation to the child. Since the adoption of the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008, it has been possible for two female parents to appear on a child’s birth certificate following birth and for two male parents to be registered following a court parental order. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 18 – 24 June 2016

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 18 – 24 June 2016 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 18 JUNE 2016 Episode 1/2 Manchester Ship Canal and eventually reaches Liverpool's Outcast from the church, community, and closest friends for a Albert Dock. SAT 00:00 John Wyndham - The Day of the Triffids crime he did not commit, Silas Marner's trust and faith falls A Ladbroke Radio production for BBC Radio 4. (b007jrll) away. A broken, disillusioned man, exiled, he builds a new SAT 08:00 Archive on 4 (b01s02zb) Episode 10 faith, that will never let him down: gold. He weaves his cloths, Dr K With most of the population blinded, Bill Masen is determined counts his money, baptises himself with the coins of his new Henry Kissinger is the most celebrated figure in US foreign to find Josella. But where does he start? Cult novel read by religion. When tragedy strikes again and all his money is stolen policy, despite having left office over thirty-five years ago. Roger May. he's bereft and grief stricken. Then on New Year's Eve a vision His much-vaunted "opening to China" with President Nixon in SAT 00:30 Sounds Natural (b01slst0) of gold flickers before the flames. Spilling locks are tumbling 1972, his détente policy with the Soviet Union during the Cold Peter Cushing coins. For a moment Silas is reunited with his lovely sovereigns. War and his shuttle diplomacy across the Middle East, all saw Award-winning actor Peter Cushing takes a break from making And then he sees a little child.