Collaborative Co-Parenting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 Cover April12.Indd

WWW.OUTMAG.CO.UK ISSUE SIXTY-FOUR 04/12 £FREE INSIDE PORTUGAL PARTYING LOS ANGELES PRIDE MADONNA’S MDNA MYRA DUBOIS Help! My man wants to open up our relationship Perfume Genius MIKE HADREAS: BOY N’ THE HOOD OUT IN THE CITY APRIL 2012 THE TEAM Hudson’s Editor DAVID HUDSON Letter [email protected] +44 (0)20 7258 1943 Design Concept Boutique Marketing www.boutiquemarketing.co.uk Graphic Designer Ryan Beal Sub Editor Chance Delgado Contributors Richard Phillips, Steven 10 Sparling, Soren Stauffer- Kruse, Josh Winning Photographer Chris Jepson Publishers CONTENTS It has been impossible to escape the news that the Sarah Garrett coalition Government intends to introduce full 04 LETTERS Linda Riley marriage equality for same-sex couples, proposing Send your Director of Advertising to allow them to hold civil marriage ceremonies on correspondence to & Exhibition Sales secular premises. editorial@outmag. Square Peg Media Despite the fact that the Government is not co.uk James McFadzean proposing to make it compulsory that any religious [email protected] group hold such ceremonies on their premises, the 06 MY LONDON + 44 (0)20 7258 1777 Catholic Church has been particularly outspoken on Rising cabaret star + 44 (0)7772 084 906 the subject. Scotland’s Cardinal Keith O’Brien Myra Dubois gives us Head of Business described the plans as “grotesque”, while the her capital highlights Development Archbishops of Westminster and Southwark jointly Lyndsey Porter wrote a public letter saying that it was the “duty” of 10 PERFUME [email protected] all Catholics to oppose such plans: “A change in the GENIUS PHOTO © CHRIS JEPSON39 + 44 (0)20 7258 1777 law would gradually and inevitably transform Seattle-based singer albums by Madonna, 42 OUTNEWS Advertising Manager society’s understanding of the purpose of marriage. -

Do Children Have Rights?

Do Children Have Rights? Five theoretical reflections on children's rights Mhairi Catherine Cowden A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University June 2012 Declaration This work is the result of original research carried out by the author. Where joint research was undertaken during the candidature and used in this thesis, it has been acknowledged as such in the body of the text. The applicable research is listed below, alongside the contribution from the author. Chapter Three: the paper 'Capacity' and 'Competence' in the Language of Children's Rights is co-authored with Joanne C Lau (Australian National University). The paper constitutes equal contribution between authors in conceiving the core argument and writing the text. Mhairi Catherine Cowden 29th June 2012 Acknowledgments The idea for this thesis first arose after I was asked several years ago to write a brief article for the UNICEF newsletter entitled, 'What are rights and why children have them'. After doing some preliminary reading I found that surprisingly there was a lack of consensus on either question. It struck me that without such foundational theory that rhetoric to secure and expand children's rights seemed fairly empty. A country built on shaky foundations. Bringing this project to fruition, however, was a lot harder than identifying the problem. I could not have done it without the help of many people. First thanks must go to my principal supervisor, Keith Dowding. Without his help and guidance I would never have read Hohfeld nor got past the first paper of this thesis. -

Satirical Legal Studies: from the Legists to the Lizard

Michigan Law Review Volume 103 Issue 3 2004 Satirical Legal Studies: From the Legists to the Lizard Peter Goodrich Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Peter Goodrich, Satirical Legal Studies: From the Legists to the Lizard, 103 MICH. L. REV. 397 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol103/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SATIRICAL LEGAL STUDIES: FROM THE LEGISTS TO THE LIZARD Peter Goodrich* ANALYTICAL TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................... .............................................. ........ .... ..... ..... 399 I. FRAGMENTA ANTIQUITATIS (THE ENDURING TRADITION) .. 415 A. The Civilian Tradition .......................................................... 416 B. The Sermon on the Laws ......................... ............................. 419 C. Satirical Themes ....................... ............................................. 422 1. Personification .... ............................................................. 422 2. Novelty ....................................... -

Ross and Olivecrona on Rights

Scholarship Repository University of Minnesota Law School Articles Faculty Scholarship 2009 Ross and Olivecrona on Rights Brian H. Bix University of Minnesota Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian H. Bix, Ross and Olivecrona on Rights, 34 AUSTL. J. LEG. PHIL. 103 (2009), available at https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/211. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in the Faculty Scholarship collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ross and Olivecrona on Rights BRIAN H. BIX1 Introduction The Scandinavian legal realists, critically-inclined theorists from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, who wrote in the early and middle decades of the 20t century,2 are not as widely read as they once were in Britain, and they seemed never to have received much attention in the United States. This is unfortunate, as the work of those theorists, at their best, is as sharp in its criticisms and as sophisticated philosophically as anything written by the better known (at least better known in Britain and the United States) American legal realists, who were writing at roughly the same time. The focus of the present article, Alf Ross and Karl Olivecrona, were arguably the most accessible of the Scandinavian legal realists, with their clear prose, straight- forward style of argumentation, and the availability of a number of works in English. -

Summer Reading Challenge 2020

Join the Silly Squad and the Let's Get Silly Ambassadors for an afternoon (ending with a bedtime story) of family fun! The Summer Reading Challenge 2020 will launch on Friday 5 June and you can join the Silly Squad on a new adventure by setting your own personal reading challenge to complete this summer. Create a free profile to keep track of your books, reviews, and all of the special rewards you unlock along the way. You'll also find heaps of super silly activities, quizzes, videos, games and more to keep you entertained at home. This year's Challenge runs from June to September, so there is plenty of time to take part and get silly this summer. Join us on Facebook on Friday 5 June to meet our super silly Ambassadors, who will be sharing their favourite silly stories, leading a draw-along to create your very own Silly Squad character, showing us their silliest dance moves, telling their most hilarious joke and sharing so much more silly fun with us all. Once you have celebrated with the Silly Squad at the Launch Party head on over to sillysquad.org.uk to start your seriously silly summer reading Challenge! Let's Get Silly Launch Party Schedule 4.00pm - Sam & Mark (as seen on CBBC) launch the Summer Reading Challenge 2020 and introduce you to the Silly Squad - telling you how you can sign up and start your seriously silly summer 4.10pm - Comedian, author and presenter, David Baddiel, reads from his children's book The Taylor TurboChaser 4:15pm - Author Gareth P Jones reads from his book Dinosaur Detective: Catnapped! and takes us on -

Public Law Liberty, the Archetype and Diversity: a Philosophy of Judging

Page1 Public Law 2010 Liberty, the archetype and diversity: a philosophy of judging Terence Etherton Subject: Administration of justice Keywords: Human rights; Integrity; Judicial decision-making; Jurisprudence; Justice; Supreme Court Legislation: Human Rights Act 1998 *P.L. 727 A conscientious judge always wishes to reach the correct decision. It is important for us that the judge does so for we wish to live in a just society. It is usually said to be a critical feature of the advanced liberal democracy, which is Great Britain today, as of other such democracies, that it is governed by the rule of law. There is no fixed meaning to that term,1 but it would at the least carry for most people the idea of law that is ascertainable and consistently and fairly applied. How can we be certain, however, that the correct decision, that is to say, the best possible decision, or at least a legitimate one, has been reached in a case in which different judges of the highest ability, knowledge and sensitivity disagree on the outcome, and either outcome would be regarded by some other judges, lawyers and citizens as correct2 ? We are not so naive as to think that difficult and important legal decisions are merely the result of a process in the nature of an algorithm. Is there, then, an analytical and adjudicative approach that will enable the conscientious judge to be confident that the decision reached is the best possible decision, and certainly a legitimate one, even if judicial colleagues, politicians and other citizens disagree with it? These are not, of course, new questions. -

Nasty Women and the Rule of Law

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of San Francisco Nasty Women and the Rule of Law By ALICE WOOLLEY and ELYSA DARLING* “Such a nasty woman.”1 “There’s just something about her that feels castrating, overbear- ing, and scary.”2 “She undoubtedly suffered in the trial . but she was not likable.”3 “Marie Henein is a successful female lawyer at the top of her pro- fession. Total bitch.”4 “Not a feminist.”5 Introduction NO ONE ENTERS THE LEGAL PROFESSION expecting social pop- ularity—or, at least, no one should.6 But recent events create the im- * Alice Woolley is Professor of Law at the Faculty of Law, University of Calgary, and President of the International Association of Legal Ethics. Elysa Darling graduated from the University of Calgary in 2016, and currently practices law in Calgary. The authors would like to thank Amy Salyzyn and Alex Darling for their helpful comments and feedback, and Joshua Davis and the University of San Francisco School of Law for including this paper in the 2017 Workshop on Jurisprudence and Legal Ethics. 1. Daniella Diaz, Trump calls Clinton ‘a nasty woman’, CNN (Oct. 20, 2016), http:// www.cnn.com/2016/10/19/politics/donald-trump-hillary-clinton-nasty-woman [https:// perma.cc/U94K-H8L3]. 2. Yvonne A. Tamayo, Rhymes with Rich: Power, Law and the Bitch, 21 ST. THOMAS L. REV. 281, 286 (2009) (quoting Tucker Carlson on Hillary Clinton during her 2007-2008 run for the Democratic presidential nomination). 3. -

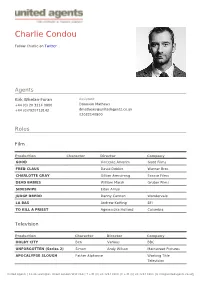

Charlie Condou

Charlie Condou Follow Charlie on Twitter Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company GOOD Vincente Amorim Good Films FRED CLAUS David Dobkin Warner Bros CHARLOTTE GRAY Gillian Armstrong Ecosse Films DEAD BABIES William Marsh Gruber Films SIDESWIPE Eitan Arrusi JUDGE DREDD Danny Cannon Wondervale LA BAS Andrew Kotting BFI TO KILL A PRIEST Agniesszka Holland Columbia Television Production Character Director Company HOLBY CITY Ben Various BBC UNFORGOTTEN (Series 2) Simon Andy Wilson Mainstreet Pictures APOCALYPSE SLOUGH Father Alphonse Working Title Television United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company CORONATION STREET Regular Various ITV THE IMPRESSIONISTS Tim Dunn & Mary BBC Downes SECRET SMILE Chris Menaul Granada MIDSOMER MURDERS Sarah Hellings Bentley Productions NATHAN BARLEY Chris Morris Hat Trick TRUST Philippa Langdale BBC THE NOBLE AND SILVER SHOW Gary Reich E4 HG WELLS Robert Young Hallmark URBAN GOTHIC Omar Madha Channel 5 PEAK PRACTICE Ken Grieve Carlton GIMME, GIMME, GIMME Liddy Oldroyd Tiger Aspect HONKEY SAUSAGES John McFarlane Radical Media ARMSTRONG & MILLER Matt Lipsey Channel 4 THE BILL Chris Lovett Thames TV PIE IN THE SKY Danny Hiller Select TV MARTIN CHUZZLEWIT Pedr James BBC CASUALTY Alan Waring BBC RIDES Andrew MacDonald Central THE STORY TELLER Paul Weiland TVS Films EVERY BREATH YOU TAKE Paul Seed Granada Stage Production Character Director Company THE CRUCIBLE Rev. Hale Douglas Rintoul Sell A Door NEXT FALL Luke Sheppard Southwark Playhouse DYING FOR IT Anna Mackmin The Almedia THE CHANGELING Dawn Walton Southwark Playhouse SHOPPING & F***ING Max Stafford-Clark No 1. -

The Law As a Moral Enterprise Fifth Annual John Courtney Murray Lecture— November 14, 2013

The Law As a Moral Enterprise Fifth Annual John Courtney Murray Lecture— November 14, 2013 Robert John Araujo, S.J., John Courtney Murray, S.J. University Professor, Loyola University Chicago I. Introduction First of all, I want to thank you for being at this lecture this evening. I am grateful for your attendance and participation!1 In preparing my remarks for this fifth lecture in a series that I pray will continue, I recalled that this fall marks the fortieth anniversary of my admission to the bar and membership in the legal profession. During these four decades, I have often heard thoughtful individuals, both professional and lay, assert that the law and morality are separate institutions. But I also recall being told something quite different by other equally thoughtful individuals—i.e., there is an overlap or an intersection between law and morality—perhaps, even an inextricable and necessary link between the two. Josiah Royce may well have been on to something to this lecture when he suggested that there exists a “moral burden of the individual”2 in his consideration of the role of the human person in society. Of course, this role includes the making and administration of law. Royce’s thoughts were further developed by the Yale historian, Robert L. Calhoun, who, in his comments on Royce, suggested that it is imperative to proper human development that the individual person 1 This lecture was not delivered as scheduled due to medical issues experienced by the author. 2 Robert L. Calhoun, Democracy and Natural Law, 5 NATURAL LAW FORUM 31, 46 (1960). -

Reading Is Positivist Legal Ethics an Oxymoron?

Is Positivist Legal Ethics an Oxymoron? ALICE WOOLLEY* ABSTRACT Positivist legal ethics defines the duties of lawyers in light of the structure and ethics of law, and the relationship between the system of laws and those to whom it applies. But is positivist legal ethics in fact a theory of legal ethics? That is, does it identify the ethical principles and virtues of the good lawyer? This paper argues that it does not. Positivist legal ethics provides a theory of the ethics of law, from which it identifies the duties with which lawyers must comply. The duties it identifies are legal, not moral or ethical. That does not make positivist legal ethics wrong, but it does have important implications for the scope and limits of the theory. It means certain questions are central to positivist legal ethics that may not be that important to other theories (e.g., how law ought to be interpreted or reformed). But at the same time there are other questions that positivist legal ethics cannot answer. Moral questions left to law yers’ discretion or that the law does not address, and the point at which a law yer may simply be unwilling to violate moral norms even if her role requires it, are things which positivist legal ethics cannot illuminate. Understanding the scope and limits of positivist legal ethics is essential for those who want to write and teach from that perspective, as well as for those who challenge it. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................... 78 I. POSITIVIST LEGAL ETHICS ............................ 83 A. THE POSITIVIST PERSPECTIVE ON LAW ............. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND LAW School of Law Agamben, the Exception and Law by Thomas Michael Frost Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 ii iii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND LAW SCHOOL OF LAW Doctor of Philosophy AGAMBEN, THE EXCEPTION AND LAW by Thomas Michael Frost Giorgio Agamben‘s work has been at the forefront of modern debates surrounding sovereign exceptionalism and emergency powers. His theory of the state of exception and engagements with Michel Foucault appear to focus upon sovereign power‘s ability to remove legal protections from life with impunity, described by the figure of homo sacer. Much secondary scholarship concentrates upon this engagement. This thesis contends that this approach is too narrow and assimilates Agamben‘s work into Foucault‘s own thought. -

Constructing Human Dignity: an Investment Concept Submitted By

Daniel Bedford 31/10/2015 Constructing Human Dignity: An Investment Concept Submitted by Daniel Jonathan William Bedford to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law In December 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: 1 Daniel Bedford 31/10/2015 2 Daniel Bedford 31/10/2015 Abstract: This thesis explores the meaning of human dignity in law and its potential value as a legal concept. It claims that existing methods of analysis are predominantly caught up with seeking a fixed and conventional meaning, which has proven difficult and has invariably led to claims that the concept is vague or vacuous. In this light, the thesis proposes a fresh method of conceptual analysis that progresses the current debate on the meaning of the concept in a more fruitful and productive direction. It seeks to shift the focus of analysis away from the formal search for a clear concept that is simply there to be applied or repeated, in favour of constructing the concept to respond to the shifting problems that emerge in life, as well as unlocking new pathways to promote more dynamic, rich, active and joyful modes of living.