Nearchus, Guides, and Place Names on Alexander's Expedition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium*

Pliny the Elder and the Problem of Regnum Hereditarium* MELINDA SZEKELY Pliny the Elder writes the following about the king of Taprobane1 in the sixth book of his Natural History: "eligi regem a populo senecta clementiaque, liberos non ha- bentem, et, si postea gignat, abdicari, ne fiat hereditarium regnum."2 This account es- caped the attention of the majority of scholars who studied Pliny in spite of the fact that this sentence raises three interesting and debated questions: the election of the king, deposal of the king and the heredity of the monarchy. The issue con- cerning the account of Taprobane is that Pliny here - unlike other reports on the East - does not only use the works of former Greek and Roman authors, but he also makes a note of the account of the envoys from Ceylon arriving in Rome in the first century A. D. in his work.3 We cannot exclude the possibility that Pliny himself met the envoys though this assumption is not verifiable.4 First let us consider whether the form of rule described by Pliny really existed in Taprobane. We have several sources dealing with India indicating that the idea of that old and gentle king depicted in Pliny's sentence seems to be just the oppo- * The study was supported by OTKA grant No. T13034550. 1 Ancient name of Sri Lanka (until 1972, Ceylon). 2 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 89. Pliny, Natural History, Cambridge-London 1989, [19421], with an English translation by H. Rackham. 3 Plin. N. H. 6, 24, 85-91. Concerning the Singhalese envoys cf. -

Alexander the Great

RESOURCE GUIDE Booth Library Eastern Illinois University Alexander the Great A Selected List of Resources Booth Library has a large collection of learning resources to support the study of Alexander the Great by undergraduates, graduates and faculty. These materials are held in the reference collection, the main book holdings, the journal collection and the online full-text databases. Books and journal articles from other libraries may be obtained using interlibrary loan. This is a subject guide to selected works in this field that are held by the library. The citations on this list represent only a small portion of the available literature owned by Booth Library. Additional materials can be found by searching the EIU Online Catalog. To find books, browse the shelves in these call numbers for the following subject areas: DE1 to DE100 History of the Greco-Roman World DF10 to DF951 History of Greece DF10 to DF289 Ancient Greece DF232.5 to DF233.8 Macedonian Epoch. Age of Philip. 359-336 B.C. DF234 to DF234.9 Alexander the Great, 336-323 B.C. DF235 to DF238.9 Hellenistic Period, 323-146.B.C. REFERENCE SOURCES Cambridge Companion to the Hellenistic World ………………………………………. Ref DE86 .C35 2006 Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World ……………………………………………… Ref DF16 .S23 1995 Who’s Who in the Greek World ……………………………………………………….. Stacks DE7.H39 2000 PLEASE REFER TO COLLECTION LOCATION GUIDE FOR LOCATION OF ALL MATERIALS ALEXANDER THE GREAT Alexander and His Successors ………………………………………………... Stacks DF234 .A44 2009x Alexander and the Hellenistic World ………………………………………………… Stacks DE83 .W43 Alexander the Conqueror: The Epic Story of the Warrior King ……………….. -

|||GET||| Alexander the Great: the Anabasis and the Indica 1St Edition

ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE ANABASIS AND THE INDICA 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Arrian | 9780191633140 | | | | | Alexander the Great Josephus Vita ipsius Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. Siege and Capture of Miletus. Lastly readers will also find three invaluable appendices, maps and site plans, and a comprehensive analytical index. Oxford University Press. Advanced embedding details, examples, and help! Campaign against the Mallians. His publications include commentaries on Curtius Rufus's histories of Alexander, including the introduction and commentary to accompany John Yardley's translation of Book 10 for the Clarendon Ancient History Series. Digression Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica 1st edition India. Capture of the Rock of Chorienes. Chapter I. A dramatic fast-moving story, told with great narrative skill, his work is now our prime and most detailed source for the history of Alexander--a compelling account of an exceptional leader, brilliant, ruthless, passionate, and complex. Views Read Edit View history. Book Description Paperback. Siege of Tyre. CMacedonian Expansion Greece : B. Destruction of Halicarnassus. The only complete English translation of Arrian available online is a rather antiquated translation by E. Facius; both E. Retrieved Alexander the Great: The Anabasis and the Indica 1st edition This manual of the Stoic moral philosophy was very popular, both among Pagans and Christians, for many centuries. Book Description Condition: New. Arrian c. Different authors have given different accounts of Alexander's life; and there is no one about whom more have written, or more at variance with each other. Ten Thousand Macedonians sent Home witli Craterus. -

4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus

Alexander’s Lovers by Andrew Chugg 4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus Barsine was by birth a minor princess of the Achaemenid Empire of the Persians, for her father, Artabazus, was the son of a Great King’s daughter.197 It is known that his father was Pharnabazus, who had married Apame, the daughter of Artaxerxes II, some time between 392 - 387BC.198 Artabazus was a senior Persian Satrap and courtier and was latterly renowned for his loyalty first to Darius, then to Alexander. Perhaps this was the outcome of a bad experience of the consequences of disloyalty earlier in his long career. In 358BC Artaxerxes III Ochus had upon his accession ordered the western Satraps to disband their mercenary armies, but this edict had eventually edged Artabazus into an unsuccessful revolt. He spent some years in exile at Philip’s court during Alexander’s childhood, starting in about 352BC and extending until around 349BC,199 at which time he became reconciled with the Great King. It is likely that his daughter Barsine and the rest of his immediate family accompanied him in his exile, so it is feasible that Barsine knew Alexander when they were both still children. Plutarch relates that she had received a “Greek upbringing”, though in point of fact this education could just as well have been delivered in Artabazus’ Satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia, where the population was predominantly ethnically Greek. As a young girl, Barsine appears to have married Mentor,200 a Greek mercenary general from Rhodes. Artabazus had previously married the sister of this Rhodian, so Barsine may have been Mentor’s niece. -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

JOSHUA P. NUDELL Alexander The

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME THIRTY-TWO: 2018 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson ò Michael Fronda òDavid Hollander Timothy Howe òJoseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller òAlex McAuley Catalina Balmacedaò Charlotte Dunn ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 32 (2018) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume thirty-two Numbers 1-2 1 Sean Manning, A Prosopography of the Followers of Cyrus the Younger 25 Eyal Meyer, Cimon’s Eurymedon Campaign Reconsidered? 44 Joshua P. Nudell, Alexander the Great and Didyma: A Reconsideration 61 Jens Jakobssen and Simon Glenn, New research on the Bactrian Tax-Receipt NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Alexander's Successors

Perdiccas, 323-320 Antigonus (western Asia Minor) 288-285 Antipater (Macedonia) 301, after Ipsus Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Archon (Babylon) Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Ptolemy (Egypt) Asander (Caria) Ptolemy (Egypt) Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Persia to Alexander the Great Atropates (northern Media) 315-311 Alexander’s Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Eumenes (Cappadocia, Pontus) vs. 318-316 Cassander Cassander (Macedonia) Laomedon (Syria) Lysimachus Daniel 11:1-4 Antigonus Demetrius (Cyprus, Tyre, Demetrius (Macedonia, Cyprus, Leonnatus (Phrygia) Ptolemy Successors Cassander Sidon, Agaean islands) Tyre, Sidon, Agaean islands) Lysimachus (Thrace) Peithon Seleucus Menander (Lydia) Ptolemy Bythinia Bythinia Olympias (Epirus) vs. 332-260 BC Seleucus Epirus Epirus “And now I will tell you the truth. Behold, three more kings are going to arise Peithon (southern Media) Antigonus Greece Greece Philippus (Bactria) vs. Aristodemus Heraclean kingdom Heraclean kingdom Ptolemy (Egypt) Demetrius in Persia. Then a fourth will gain far more riches than all of them; as soon as Eumenes Paeonia Paeonia Stasanor (Aria) Nearchus Olympias Pontus Pontus and others . Peithon Polyperchon Rhodes Rhodes he becomes strong through his riches, he will arouse the whole empire against the realm of Greece. And a mighty king will arise, and he will rule with great authority and do as he pleases.” (Dan 11:2-3) 320 330310 300 290 280 270 260 250 Antipater, 320-319 Alcetas and Attalus (Pisidia ) Antigenes (Susiana) Antigonus (army in Asia) Arrhidaeus (Phrygia) Cassander -

Buddhism in the Northern Deccan Under The

BUDDHISM IN THE NORTHERN DECCAN UNDER THE SATAVAHANA RULERS C a ' & C > - Z Z f /9> & by Jayadevanandasara Hettiarachchy Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of London 1973* ProQuest Number: 10731427 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731427 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This study deals with the history of Buddhism in the northern Deccan during the Satavahana period. The first chapter examines the evidence relating to the first appearance of Buddhism in this area, its timing and the support by the state and different sections of the population. This is followed by a discussion of the problems surrounding the chronology of the Satavahana dynasty and evidence is advanced to support the ’shorter chronology*. In the third chapter the Buddhist monuments attributable to the Satavahana period are dated utilising the chronology of the Satavahanas provided in the second chapter. The inscriptional evidence provided by these monuments is described in detail. The fourth chapter contains an analysis and description of the sects and sub-sects which constituted the Buddhist Order. -

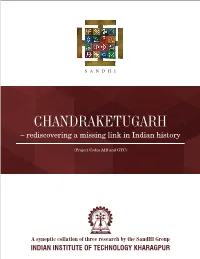

CHANDRAKETUGARH – Rediscovering a Missing Link in Indian History

CHANDRAKETUGARH – rediscovering a missing link in Indian history (Project Codes AIB and GTC) A synoptic collation of three research by the SandHI Group INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY KHARAGPUR Patron-Advisor Ms. Amita Sharma Advisor to HRM, MHRD, Government of India Former Additional Secretary (Technical), MHRD, Government of India Advisor Prof. Partha P. Chakrabarti Director, IIT Kharagpur Monitoring Cell Prof. Sunando Dasgupta Dean, Sponsored Research and Consultancy Cell, IIT Kharagpur Prof. Pallab Dasgupta Associate Dean, Sponsored Research and Consultancy Cell, IIT Kharagpur Principal Investigator (overall) Prof. Joy Sen Department of Architecture & Regional Planning, IIT Kharagpur Vide order no. F. NO. 4-26/2013-TS-1, Dt. 19-11-2013 (36 months w.e.f 15-1-2014 and 1 additional year for outreach programs) Professor-in-Charge Documentation and Dissemination Prof. Priyadarshi Patnaik Department of Humanities & Social Sciences, IIT Kharagpur Research Scholars Group (Coordinators) Sunny Bansal, Vidhu Pandey, Prerna Mandal, Arpan Paul, Deepanjan Saha Graphics Support Tanima Bhattacharya, Sandhi Research Assistant, SRIC, IIT Kharagpur ISBN: 978-93-80813-37-0 © SandHI A Science and Heritage Initiative, IIT Kharagpur Sponsored by the Ministry of Human Resources Development, Government of India Published in September 2015 www.iitkgpsandhi.org Design & Printed by Cygnus Advertising (India) Pvt. Ltd. 55B, Mirza Ghalib Street 8th Floor, Saberwal House, Kolkata - 700016 www.cygnusadvertising.in Disclaimer The information present in the Report offers the views of the authors and not of its Editorial Board or the publishers. No party involved in the preparation of material contained in SandHI Report represents or warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of such material. -

The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean

13 · The Role of Charts in Islamic Navigation in the Indian Ocean GERALD R. TIBBETTS The existence of indigenous navigational charts of the voyage.7 Barros wrote in the 1540s and could have read Indian Ocean is suggested by several early European Varthema's work, which was in many editions by that sources, the earliest of which is the brief mention of date, including an edition in Spanish published in Seville mariners' charts by Marco Polo. First, in connection with in 1520. There are other occasions when Barros seems Ceylon Polo mentions "la mapemondi des mariner de cel to have incorporated later materials into his version of mer,"! a reference that can only refer to a nautical map the earlier Portuguese accounts of the Indian Ocean, so of some sort. Second, in connection with the Indian west some doubt is cast on the accuracy of his statement. coast he refers to "Ie conpas e la scriture de sajes rnar In 1512 another possible local chart is mentioned by iner."2 This first word has been translated as "charts," Afonso de Albuquerque in a letter to the Portuguese king and strangely enough it is the very word (al-qunbii~) used Manuel. He reports that he had seen a large chart belong by Abmad ibn Majid (fl. A.D. 1460-1500) in connection ing to a pilot on which Brazil, the Indian Ocean, and the with portolan charts.3 Far East were shown. This chart can only have been very The other sources are Portuguese and come from the sketchy, for the Portuguese pilot Francisco Rodrigues period when that country had reached these parts. -

The Classical Association Annual Conference 2014 University Of

The Classical Association Annual Conference 2014 University of Nottingham ABSTRACTS (listed alphabetically by speaker’s surname) Abstracts may have been edited for reasons of space Katrina-Kay S. Alaimo (Exeter) Panel: Material Culture Using Small Finds Data for Temple Sites in Roman Britain Analysis of temple sites often mix the study of literature and that of architecture; and when there is a lack of literary evidence for a particular region, popular literature is used to draw assumptions on the social practice of that area. Understanding social practice provides insight on how people conducted their daily lives and thus is important for our comprehension of society. When attempting to understand the culture and identity of those who used a site, small finds evidence can easily be overlooked. However, when we examine the collective data relating to a small find type, such as hairpins or animal bones, interesting patterns emerge. The zonation of specific types or materials, or in the case of the animal remains – taxa, age, etc., can inform us of the social practice conducted on a specific temple site at different periods of time. Using small finds data for temple sites is particular important for studying religious practices in Roman Britain in the 1st to 2nd centuries CE since we lack substantial literary evidence. Approaches to religion within this province routinely analyse broad patterns, and it is time to start looking at each site individually in order to pinpoint the subtleties in local practices and to allow an in-depth examination of what actually happened on site. This sort of fine brush analysis is particularly relevant for data rich sites that have a significant amount of context available for its material finds. -

Hymenoptera), New to the Iranian Fauna Majid FALLAHZADEH1, Ovidiu POPOVICI2, *

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle «Grigore Antipa» Vol. 59 (1) pp. 73–79 DOI: 10.1515/travmu-2016-0012 Research paper Doddiella Kieffer: a Peculiar Genus of Platygastroidea (Hymenoptera), New to the Iranian Fauna Majid FALLAHZADEH1, Ovidiu POPOVICI2, * 1Department of Entomology, Jahrom Branch, Islamic Azad University, Jahrom, Iran. 2University Al. I. Cuza, Faculty of Biology, Carol The First Avenue No. 11, Jassy, 700506 Romania. *corresponding author, e–mail: [email protected] Received: December 22, 2015; Accepted: March 25, 2016; Available online: June 26, 2016; Printed: June 30, 2016 Abstract. Doddiella kiefferi Priesner, 1951 (Hymenoptera, Platygastroidea) is here redescribed and illustrated to facilitate its identification. This is the first record of the peculiar genusDoddiella Kieffer, 1913 from Iran. The specimens were collected by Malaise traps from Fars province in southern Iran during 2012 and 2013. Iran is the north–eastern limit in the distribution of this species. Key Words: parasitoids, scelionid wasps, Malaise trap, Iran INTRODUCTION Platygastroidea in Iran is very poorly known. The majority of reports of the Scelionidae in Iran are related to the genus Trissolcus Ashmead (e.g. Radjabi & Amir Nazari, 1989; Radjabi, 2001; Hashemi Rad et al., 2002; Iranipour & Johnson, 2010) that are the best–known egg parasitoids of some pests on agricultural crops in Iran. No comprehensive study has been done on these beneficial insects in this region so far. More than a century ago Kieffer (1913) established the genus Doddiella in honor of the reputable entomologist A. P. Dodd. This genus was created as monotypic for its type species D. nigriceps Kieffer, 1913, collected from Ghana, Côte d’Or, Aburi.