Authenticity and the Boundaries of 'Eurasian' in the Hybrid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decade Ahead

Issue 03 1 Positivity wins The Decade Ahead It's official: basic Stewards of classic Linking up with kindred Ponies got talent! bubbles are back! cocktails for the spirits beyond the Celebrating diversity generations to come industry in our team 2020 A Jigger & Pony Publication $18.00 + GST 56 2 3 Gin & Sonic Monkey 47 Gin, soda water, tonic water, grapefruit juice 25 per cocktail Prices subject to 10% service charge and 7% GST 4 5 Contents pg. Basic bubbles are back 10 Stripped down cocktails that are deceptively simple Principal Footloose and fancy fizz 16 Celebrating humankind’s fascination with things that go ‘pop’ bartender’s A sense of place 20 Embracing flavours that evoke welcome a sense of place across Asia Kindred spirits 22 Meet team Fossa, local craft chocolate makers with a passion Positivity wins! for creating new flavours Collaboration across borders 26 My bartending journey started eight years ago, around the same time that Jigger A collaboration between bartenders from & Pony was opening its doors for the first time. That was also the beginning of a opposite ends of the globe cocktail revolution that would shape the drinks world as we know it today. The boundaries of cocktail-making have been pushed to places we could never have imagined, and customer knowledge of product and drinks is stronger than ever. Passing down the 28 tradition of classics When we first started designing this menu-zine, the team reviewed the trends and Stewards of classic cocktails for stories of the past decade, and what we’ve seen is that sheer passion (and a healthy generations to come dose of positivity) can spread and influence the way people choose to enjoy the important moments of their lives. -

Menu Order Form

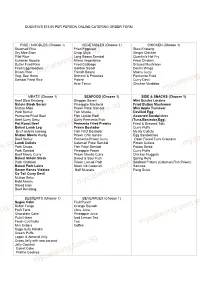

QUENTIN'S $15.00 PER PERSON ONLINE CATERING ORDER FORM RICE / NOODLES (Choose 1) VEGETABLES (Choose 1) CHICKEN (Choose 1) Steamed Rice Fried Eggplant Stew Kristang Dry Mee Siam Chap Chye Ginger Chicken Pilaf Rice Long Beans Sambal Quentin's Hot Fry Eurasian Noodle Mixed Vegetables Fried Chicken Butter Fried Rice Fried Cabbage Braised Mushroom Fried Egg Noodles Garden Salad Devil's Wings Bryani Rice French Beans Moeru Curry Veg. Bee Hoon Broccoli & Potatoes Permenta Fried Sambal Fried Rice Patchri Curry Devil Acar Timun Chicken Vindaloo MEATS (Choose 1) SEAFOOD (Choose 1) SIDE & SNACKS (Choose 1) Beef Stew Kristang Singgan Serani Mini Quiche Loraine Sirloin Steak Serani Pineapple Mackeral Fried Button Mushroom Mutton Miso Prawn Petai Sambal Mini Apple Turnover mycatering.com.sg Pork Semur mycatering.com.sg Fish Moolie Devilled Egg Permenta Fried Beef Fish Lemak Padi Assorted Sandwiches Beef Curry Seku Curry Permenta Fish (Tuna,Bostador,Egg) Pot Roast Beef Permenta Fried Prawns Fried & Dressed Tofu Baked Lamb Leg Prawn Bostador Curry Puffs Beef ambilla kacang Fish Fillet Bostador Meaty Cutlets Mutton Moeru Curry Prawn Chili Garam Egg Sandwiches Beef Semur Permenta Prawn Curry Open Faced Tuna Croutons Lamb Cutlets Calamari Petai Sambal Potato Cutlets Pork Chops Fish Petai Sambal Potato Salad Pork Sambal Pineapple Prawn Curry Puffs Beef Moeru Curry Prawn Moolie Curry Chicken Nuggets Baked Sirloin Steak Sweet & Sour Fish Spring Rolls Pork Vindaloo Prawn Lemak Padi Seafood Fritters (Calamari,Fish,Prawn) mycatering.com.sg Baked Pork Loins mycatering.com.sg -

Singapore Dishes TABLE of CONTENTS

RECIPE BOOKLET ERIC M A’ A S C O D O N K A E R B R Singapore Dishes TABLE OF CONTENTS COOKING WITH PRESSURE ................................................. 3 VENTING METHODS ................................................................ 4 INSTANT POT FUNCTIONS COOKING TIME ................... 5 MAINS HAINANESE CHICKEN RICE .................................................. 6 STEAMED SHRIMP GLASS VERMICELLI .......................... 8 MUSHROOM & SCALLOP RISOTTO ................................... 10 CHICKEN VEGGIE MAC AND CHEESE............................... 12 HAINANESE HERBAL MUTTON SOUP.............................. 14 STICKY RICE DUMPLINGS ..................................................... 16 CURRY CHICKEN ....................................................................... 18 TEOCHEW BRAISED DUCK ................................................... 19 CHICKEN CENTURY EGG CONGEE .................................... 21 DESSERTS PULOT HITAM ............................................................................ 22 STEAMED SUGEE CAKE ........................................................ 23 PANDAN CAKE........................................................................... 25 Cooking with Pressure FAST The contents of the pressure cooker cooks at a higher temperature than what can be achieved by a conventional Add boil — more heat means more speed. ingredients Pressure cooking is about twice as fast as conventional cooking (sometimes, faster!) & liquid to Instant Pot® HEALTHY Pressure cooking is one of the healthiest -

C a N D L E N

COMODEMPSEY.SG C A N D L E N U T 1800 304 2288 [email protected] The world’s first Michelin-starred Peranakan restaurant, Candlenut takes a contemporary yet authentic approach to traditional Straits-Chinese cuisine. The restaurant serves up refined Peranakan cuisine that preserves the essence and complexities of traditional food, with astute twists that lift the often rich dishes to a different level. Executive Head Chef and Owner, Malcolm Lee’s degustation menus are carefully crafted on a frequent basis, ensuring a new and exciting culinary experience each time. A B O U T Malcolm Lee Executive Head Chef and owner, Malcolm Lee’s passion in cooking was sparked by his mother and grandmother. He started Candlenut at a young age of 25 striving to create refined and inspired Peranakan dishes reminiscent of the yesteryears. Chef Malcolm commits to using only the freshest seasonal produce available, without comprising on taste of quality. Today, Candlenut is internationally recognised as the world’s first and only Michelin starred restaurant serving local Singapore flavours and favourites. Chef Malcolm himself, alongside his talented kitchen and front of house team, are more than happy to work with you to customize any individual or communal style dining packages for your event. P R I V A T E E V E N T For a group of up to a maximum of 90 guests our restaurant is perfect! The Venue offers a private lawn giving guests a unique yet casual space for Canapés and Drinks. D E T A I L S MINIMUM SPEND LUNCH DINNER 12 PM – 3.30 PM 6 PM – 10.30 PM Monday-Thursday S$ 8,000++ S$ 12,000++ Friday- Sunday & S$ 10,000++ S$ 15,000++ Public Holiday CAPACITY Sit down event: Up to 90 guests, inclusive of private dining room for 10 guests. -

C a N D L E N U T Circuit Breaker Menu

C A N D L E N U T Circuit Breaker Menu STARTERS Bakwan Kepiting Soup $20 Blue Swimmer crab chicken balls, bamboo shoot, rich chicken broth boiled over 4 hours – Individual Portion Ngoh Hiang $20 Minced pork, prawns, shiitake mushroom, water chestnut wrapped in crispy deep fried beancurd skin Snake River Farm Kurobuta Pork Neck Satay $20 Glazed with kicap manis, grilled and smoked over charcoal – 4 skewers CURRIES & BRAISES Chap Chye $20 Cabbage, black mushroom, pork belly, lily buds, black fungus, vermicelli braised in rich prawn stock Chef’s Mum’s Chicken Curry $20 A signature dish of my mother, a must have dish at every family special occasion, Toh Thye San Chicken cooked with potato, kaffir lime leaf Westholme Wagyu Beef Rib Rendang $20 Dry caramelised curry cooked over 4 hours with spices and turmeric leaf garnished with Serunding Aunt Caroline’s Babi Buah Keluak $20 Slow cooked Free- range Borrowdale Pork soft bone with an aromatic and intense “poisonous” black nut gravy Blue Swimmer Crab Curry $20 A Candlenut signature, turmeric, galangal, kaffir lime leaf Babi Pongteh $20 Slow braised Borrowdale free range pork belly, shitake mushrooms, preserved soy bean paste, spoon cut chilli Ikan Assam Pedas $20 Kühlbarra ocean barramundi fillet cooked in a spicy tangy gravy with baby okra, brinjal and honey pineapple Ikan Chuan Chuan $20 Local red lion snapper fillet fried and coated in an aromatic fermented soy bean and ginger sauce, fried ginger strips CHINESE WOK Chincalok Omelette $20 House fermented baby shrimp, also known as grago, Freedom range co. eggs, spring onion, crab meat Candlenut’s Buah Keluak Fried Rice $20 Fried with rich Indonesian black nut sambal, Freedom range co. -

Title Multiculturalism: a Study of Plurality and Solidarity in Colonial

Title Multiculturalism: A study of plurality and solidarity in colonial Singapore Author(s) Phyllis Ghim-lian Chew Source BiblioAsia, 6(4), 14-18 Published by National Library Board, Singapore This document may be used for private study or research purpose only. This document or any part of it may not be duplicated and/or distributed without permission of the copyright owner. The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. This article was produced for BiblioAsia (Volume 6, Issue 4, 2011), a publication of the National Library Board, Singapore. © 2011 National Library Board, Singapore Archived with permission of the copyright owner. Feature Multiculturalism : A Study of Plurality and Solidarity in Colonial Singapore By Phyllis Ghim-lian Chew Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2010) National Library Some foods have become such a part of everyday life in and assimilatiOn that lay htdden beneath the seemingly divisive Singapore that the1r origins have been largely forgotten. and veneer of multiculturalism. various races have each claimed these dishes as part of their traditional cuisines. Examples of some of these foods include A THREE-GENERATION MODEL: THE PLURALITY- sugee cake. fruit cake, pineapple tart. agar-agar. curry puff, SOLIDARITY CLINE meat patty, butter cake and kaya; these are believed to have Our acculturation-assimilation cont1nuum begins with plurality originated from the Eurasian community (Marbeck. 2004). In at one end, and solidarity at the other. While plurality conjures a similar way, the following dishes and desserts that are part images of dissent and divisiveness, solidarity connotes of the mainstream Malay menu, were originally Chinese: char cooperation and peaceful exchange. -

Ahh-Yum MCO Menu 2020-04-14

Daging Masak Lemak Cili Padi RM 15.90 RM 19.90 Sup Tulang Daging RM 15.90 RM 19.90 Nasi ahh-yum Nasi Ahh-Yum RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Nasi Lemon Chicken Nasi lemak basmathi RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Ahh-Yum Berempah RM 12.90 RM 15.90 Nasi ahh-mah Ahh-Yum Rendang New! RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Kung Pao Chicken RM 10.30 Beef Rendang RM 12.90 RM 16.90 RM 12.90 Golden Butter Chicken RM 10.30 RM 12.90 Sambal Sotong RM 12.90 RM 15.90 Soy Braised Chicken & Potato RM 10.30 RM 12.90 CHOICE OF KU AH ASAM LEMAK PEDAS CILI PADI CURRY KUNG KAMPONG PAO AH Nasi bunga telang CHOICE OF KU CREAMY ASAM LEMAK Ahh-Wsome! RM 23.90 RM 29.90 HAINANESE Up BUTTER PEDAS CILI PADI to Ahh-Yum Berempah, Kambing Bakar & Sambal Sotong Ahh-Yum Berempah RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Ahh-Yum Rendang New! RM 12.90 RM 16.90 western konfusion Beef Rendang RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Ahh-Yum Chop RM 12.90 RM 19.90 Kambing Bakar RM 14.30 RM 17.90 Lamb Chop New! RM 19.90 RM 24.90 Sambal sotong RM 13.50 RM 16.90 Spaghetti Bolognese RM 12.90 RM 18.90 Beef / Chicken Grilled Kambing RM 19.90 RM 24.90 35% Chicken Lasagna RM 12.90 RM 14.90 until 28th April 2020 Sambal Udang Petai RM 19.90 RM 24.90 Mac & Cheese RM 12.90 RM 14.90 No Aed MSG, No Aed Artificial Colouring, No Aed Preservatives noodles dim-sum light munch share-share Nyonya Laksam RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Siew Mai RM 8.00 RM 8.90 / 3pcs Karipap XL RM 2.80 RM 3.50/ pc Lorbak Ahh-Yum RM 11.90 RM 14.90 / 3pcs Chicken & Egg Mihun Siam RM 12.90 RM 16.90 Salted Egg Mai RM 8.00 RM 8.90 / 3pcs Tofu Ahh-Yum RM 6.30 RM 7.90 / 4pcs Karipap XL RM 2.80 RM 3.50/ pc Curry Laksa RM 12.90 -

Classic Flavors

Classic Flavors (available in all sizes) *Keep in mind that the flavor components will be incorporated and configured per the decorators’ discretion in order to accommodate the cake size and custom decoration you’re looking for. All Flavor cakes are approximately 5” tall and come with three layers of cake and two layers of filling. Be advised that we do not make vegan cakes. Instead, we offer plenty of vegan cupcake flavors as a great alternative. We do make gluten-free cakes. Most of the flavors listed below are available in gluten-free. *Flavors that are not available in gluten-free will be denoted with a red star.* Classic Vanilla Vanilla cake, vanilla buttercream Classic Chocolate Chocolate cake, vanilla buttercream Vanilla Chocolate Vanilla cake, chocolate buttercream Classic Marble Marbled vanilla and chocolate cake, vanilla buttercream Classic Funfetti Funfetti cake, vanilla buttercream Classic Fruit Filling Vanilla or chocolate cake, fruit compote, curd, or buttercream (fruit filling flavors include Strawberry, Raspberry, Lemon, Lime, and Apple when in season) *Cookies ‘n Cream Chocolate cake, Oreo cookies ‘n cream buttercream Decadent Chocolate Chocolate cake, chocolate ganache Red Velvet Red velvet cake, cream cheese Black Bottom Chocolate cake, cream cheese & mini chocolate chips Snickerdoodle Cinnamon cake, cinnamon cream cheese Chocolate Peanut Butter Chocolate cake, rich peanut butter Salted Caramel Chocolate cake, salted caramel buttercream Luscious Lemon Lemon cake, lemon curd or buttercream Coconut Coconut cake, vanilla -

Biblioasia Jan-Mar 2021.Pdf

Vol. 16 Issue 04 2021 JAN–MAR 10 / The Mystery of Madras Chunam 24 / Remembering Robinsons 30 / Stories From the Stacks 36 / Let There Be Light 42 / A Convict Made Good 48 / The Young Ones A Labour OF Love The Origins of Kueh Lapis p. 4 I think we can all agree that 2020 was a challenging year. Like many people, I’m looking Director’s forward to a much better year ahead. And for those of us with a sweet tooth, what better way to start 2021 than to tuck into PRESERVING THE SOUNDS OF SINGAPORE buttery rich kueh lapis? Christopher Tan’s essay on the origins of this mouth-watering layered Note cake from Indonesia – made of eggs, butter, flour and spices – is a feast for the senses, and very timely too, given the upcoming Lunar New Year. The clacking of a typewriter, the beeping of a pager and the Still on the subject of eggs, you should read Yeo Kang Shua’s examination of Madraschunam , the plaster made from, among other things, egg white and sugar. It is widely believed to have shrill ringing of an analogue telephone – have you heard these been used on the interior walls of St Andrew’s Cathedral. Kang Shua sets the record straight. sounds before? Sounds can paint images in the mind and evoke Given the current predilection for toppling statues of contentious historical figures, poet and playwright Ng Yi-Sheng argues that Raffles has already been knocked off his pedestal – shared memories. figuratively speaking that is. From a familiar historical figure, we turn to a relatively unknown personality – Kunnuck Mistree, a former Indian convict who remade himself into a successful and respectable member of society. -

Shellycakes Business Plan

ShellyCakes “Always a Sweet Treat” Wedding cake Michelle made for her own wedding. May 2008 Michelle L. Schutten 5 Holly Lane Butte, MT 59701 406.214.9202 [email protected] The components of this business plan have been submitted on a confidential basis. It may not be reproduced, stored, or copied in any form. By accepting delivery of this plan the recipient agrees to return this copy of the plan. Do not copy, fax, reproduce or distribute without permission. Copy __ ShellyCakes 1 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Business .......................................................................................... 2 1.2 Business Opportunity ...................................................................... 2 1.3 Competitive Strategy ....................................................................... 2 1.4 Economics of the Business .............................................................. 2 1.5 Founder ........................................................................................... 2 2. Business 2.1 Mission Statement .......................................................................... 4 2.2 Description of the Business ............................................................ 4 2.3 Form of Incorporation .................................................................... 5 2.4 Products and Services .................................................................... 5 2.5 Industry Analysis ........................................................................... 6 2.6 Market Analysis ............................................................................ -

全文本) Acceptance for Registration (Full Version)

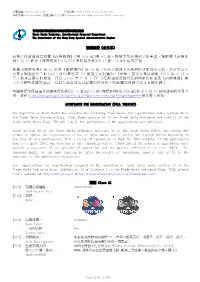

公報編號 Journal No.: 596 公布日期 Publication Date: 05-09-2014 分項名稱 Section Name: 接納註冊 (全文本) Acceptance for Registration (Full Version) 香港特別行政區政府知識產權署商標註冊處 Trade Marks Registry, Intellectual Property Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 接納註冊 (全文本) 商標註冊處處長已根據《商標條例》(第 559 章)第 42 條,接納下列商標的註冊申請。現根據《商標條 例》第 43 條及《商標規則》(第 559 章附屬法例)第 15 條,公布申請的詳情。 根據《商標條例》第 44 條及《商標規則》第 16 條,任何人擬就下列商標的註冊提出反對,須在本公告 公布日期起計的三個月內,採用表格第 T6 號提交反對通知。(例如,若果公布日期爲 2003 年 4 月 4 日,則該三個月的最後一日爲 2003 年 7 月 3 日。)反對通知須載有反對理由的陳述及《商標規則》第 16(2)條所提述的事宜。反對人須在提交反對通知的同時,將該通知的副本送交有關申請人。 有關商標註冊處處長根據商標條例(第 43 章)第 13 條/商標條例(第 559 章)附表 5 第 10 條所接納的註冊申 請,請到 http://www.gld.gov.hk/cgi-bin/gld/egazette/index.cgi?lang=c&agree=0 檢視電子憲報。 ACCEPTANCE FOR REGISTRATION (FULL VERSION) The Registrar of Trade Marks has accepted the following trade marks for registration under section 42 of the Trade Marks Ordinance (Cap. 559). Under section 43 of the Trade Marks Ordinance and rule 15 of the Trade Marks Rules (Cap. 559 sub. leg.), the particulars of the applications are published. Under section 44 of the Trade Marks Ordinance and rule 16 of the Trade Marks Rules, any person who wishes to oppose the registration of any of these marks shall, within the 3-month period beginning on the date of this publication, file a notice of opposition on Form T6. (For example, if the publication date is 4 April 2003, the last day of the 3-month period is 3 July 2003.) The notice of opposition shall include a statement of the grounds of opposition and the matters referred to in rule 16(2). -

Persian Love Cake This Love Cake Is a Beautiful One to Bake up Around Valentines Day Or on Any Special Occasion

Persian Love Cake This love cake is a beautiful one to bake up around Valentines Day or on any special occasion. With strong citrus flavors and subtle hints from spices, you will finish off this cake by poking holes and pouring hot syrup over the top, locking in moistness and sweetness. Ingredients Yield: Two 6’’ cakes -or- One 9’’ cake Prep Time: 20 min Cook Time: 50 min - 1 hr CAKE SYRUP 3 1/2 c Blonde Beauty flour 1/3 c lemon juice (roughly 2 lemons) 1 1/2 tsp cream of tartar* 1/3 c white sugar 1 1/2 tsp baking soda* 1 tsp rosewater -or- 2 - 3 tsp brewed rose tea 1 1/2 tsp ground cardamom 1/2 tsp ground nutmeg 8 tbs room temperature butter 3/4 c packed brown sugar 3/4 c white sugar 2 large eggs, or three medium eggs 1 c plain yogurt Zest of one orange 1/4 c raw chopped pistachios (or almonds)** Instructions Preheat your oven to 350 degrees. Grease your cake pans and put a bit of parchment paper on the bottom. In a medium sized bowl combine your dry ingredients, flour, cream of tartar, baking soda, cardamom, and nutmeg. Using a stand mixer, cream the butter and sugars together, then add the eggs and beat until fluffy. Next add the yogurt and orange zest. Lastly slowly incorporate the dry ingredients and mix until well blended. Pour the batter into your prepped pans and top with the chopped nuts. Bake for 50 min to 1 hr, or until a skewer comes out clean.