An Approach to Making History Popular, Relevant, and Intellectual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reference Guide for Service Science Curriculum Development, Recommended by S3tw

A Reference Guide for Service Science Curriculum Development, recommended by s3tw A Reference Guide for Service Science Curriculum Development Recommended by Service Science Society of Taiwan ( s3tw ) February 20, 2012 (Version 0.92) Abstract Service science consists of knowledge and practice from various disciplines, such as management, engineering, design, and social science. This emerging discipline needs a reference guide in developing interdisciplinary curriculum for those first movers to launch service science related programs. In this reference guide, we present the progressive version of core courses to compose the curriculum for a master program on service science. There are 13 courses including the essential knowledge and abilities of interdisciplinary study of service science in order to cultivate T-shape service science professionals. These course structures and contents were recommended through a joint effort of scholars in constituent disciplines of service science. We expect this reference guide of curriculum framework and contents as the foundation to contribute to the continuous efforts on developing the detailed course learning activities in class teaching. Then, instructors of these recommended courses can enhance the frameworks and contents through the feedback from teaching. Moreover, we hope the derivation of related courses from these core courses can further connect service science with existing various academic programs. We expect the interdisciplinary efforts on service science development contribute to the cultivation of service science talents to achieve the wellbeing of modern societies. i A Reference Guide for Service Science Curriculum Development, recommended by s3tw TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND ……………………………………………………. 1 2. COURSE STRUCTURE ……………………………………………. 4 3. LIST OF COURSES ………………………………………………… 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ………………………………………………. -

Enslaved African Muslims in American Literature

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-23-2017 12:00 AM Islam's Low Mutterings at High Tide: Enslaved African Muslims in American Literature Zeinab McHeimech The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Thy Phu The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Dr. Julia Emberley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Zeinab McHeimech 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation McHeimech, Zeinab, "Islam's Low Mutterings at High Tide: Enslaved African Muslims in American Literature" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4705. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4705 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation traces the underexplored figure of the African Muslim slave in American literature and proposes a new way to examine Islam in American cultural texts. It introduces a methodology for reading the traces of Islam called Allahgraphy: a method of interpretation that is attentive to Islamic studies and rhetorical techniques and that takes the surface as a profound source of meaning. This interpretative practice draws on postsecular theory, Islamic epistemology, and “post-critique” scholarship. Because of this confluence of diverse theories and epistemologies, Allahgraphy blurs religious and secular categories by deploying religious concepts for literary exegesis. -

09 12 16 Dec

SPRING INTO PEACE, LOVE, AND MEALS DEC '18 09 NUCLEAR WINTER 12 TACO GREASE 16 WITH MALES EXCHEQUER RESTAURANT - PUB (312) 939-5633 exchequerpub.com 226 S. Wabash Chicago Style Pizza - Ribs - Classic American Dining F Newsmagazine is a journal of arts, culture, and politics, edited and designed by students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The print edition is published eight times a year and the web edition is published year-round. December 2018 Cream of the Crop Food Art Director Unyimeabasi Udoh Assistant Art Director Ishita Dharap Six Cool Restaurants That Are Welcome to Flavortown Comics Editor Katie Wittenberg Too Cool For You Guy Fieri will teach at the School of the Photography Editor John Choi 04 Infi nite Yelp stars by Pastry Parcel 12 Art Institute of Chicago by Phil Awful Staff Designers Catherine Cao, Ishita Dharap, Shannon Lewis, Unyimeabasi Udoh, Katie Wittenberg Tonight, We Dine In Vegan Hell Not Your Mother’s Slow Cooker Cherry on Top One family’s harrowing journey in search From kitchen appliance to groundbreaking Managing Editors Casey Carsel, Grace Wells 05 of Chili’s by Whale Grits 14 art installation by Pastry Parcel Design Advisor Michael Miner Editorial Advisor Paul Elitzik Five Foods We Haven’t Eaten Since Meals for the Overeducated and Underfed Piece of Cake the Fall of Atlantis The secret ingredient is tears Webmaster Daniel Brookman 06 The foods you wish you could still Instagram 15 by Whale Grits Ad Manager Hyelee Won by Custard Doughman Distributors Riley Lynch, Jiatan Xiao Ballad of the Sad Salad -

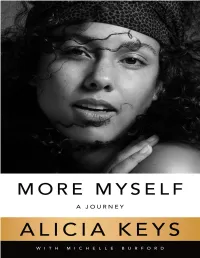

Alicia Keys, Click Here

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Authors Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Flatiron Books ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on Alicia Keys, click here. For email updates on Michelle Burford, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. This book is dedicated to the journey, and all the people who are walking with me on it … past, present, and future. You have all helped me to become more myself and I am deeply grateful. FIRST WORD The moment in between what you once were, and who you are now becoming, is where the dance of life really takes place. —Barbara De Angelis, spiritual teacher I am seven. My mom and I are side by side in the back seat of a yellow taxi, making our way up Eleventh Avenue in Manhattan on a dead-cold day in December. We hardly ever take cabs. They’re a luxury for a single parent and part-time actress. But on this afternoon, maybe because Mom has just finished an audition near my school, PS 116 on East Thirty-third Street, or maybe because it’s so freezing we can see our breath, she picks me up. -

Diaries 1701-1770

1701AD ANONYMOUS - B54 May 1701 Matthews: Political diary (extract); political affairs of the day. Notes and Queries Second Series, X, 1860, pp 324-325. ASTRY, Diana (later Mrs. ORLEBAR) (1671-1716) of Henbury, Gloucestershire - B54 September 1701 to September 1708 Matthews: Social diary (extracts); her marriage; country social life; visits; much about meals, dinners, and menus; visits to London; mostly gastronomic interest; very interesting spellings. Orlebar Chronicles by Frederica St.John Orlebar. London, 1930, pp 160-168. 01 BLEEKER, Johannes [Capt.] (see also GLEN, 1699) - A16,M129 June 1701 Matthews: Treaty journal; journey with David Schuyler to Onondaga and negotiations with Indians. In Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York IV, by E.B.O'Callaghan. 1854, pp 889-895. 03 DRURY, Robert (b.1687) English sailor - E,F 1701 to 1717 (?) “The Degrave left port in February 1701 reaching India safely four months later. On the return voyage it ran aground near Mauritius, and the crew was forced to abandon ship in Madagascar on the southernmost tip of the island, … A reluctant slave at first, Robert eventually moved his way up from agricultural work to become a cow herd and eventually the royal butcher.” Madagascar: Or, Robert Drury’s Journal during Fifteen years Captivity on that Island Unwin, 1890. First published in 1729; many later printings. The authenticity of the journal is disputed and it may fiction by Daniel Defoe, based on borrowings from The history of Madagascar by Etienne de Flacourt. 01 MAHER, John - mate of sloop Mary (?) - A16,M130 October to November 1701 Matthews: Sea journal; voyage of the Mary from Quebec and account of her wreck off Montauk Point, Long Island. -

How Citizen Reporters Build Hyperlocal Communities

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2006 Grassroots journalism in your own backyard: How citizen reporters build hyperlocal communities Jan Lauren Boyles West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Boyles, Jan Lauren, "Grassroots journalism in your own backyard: How citizen reporters build hyperlocal communities" (2006). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3226. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3226 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grassroots Journalism in Your Own Backyard: How Citizen Reporters Build Hyperlocal Communities Jan Lauren Boyles Thesis submitted to the P.I. Reed School of Journalism at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Journalism Ralph E. Hanson, Ph.D., Chair Maryanne Reed, M.S., Dean John Temple, M.F.A. Jeffrey Worsham, Ph.D. School of Journalism Morgantown, West Virginia 2006 Keywords: hyperlocal media, citizen journalism, mainstream media, blog Copyright 2006 Jan Boyles ABSTRACT Grassroots Journalism in Your Own Backyard: How Citizen Reporters Build Hyperlocal Communities Jan Lauren Boyles Americans are flocking to the Internet for news and information. -

Handley Bib 4Ed V.IV

380 Bibliography of Diaries Printed in English [1997-1998 1780AD 01 ANONYMOUS A154,M1271 August 1780 to May 1781 Matthews: Military journal (extracts); pages from the diary of a common soldier; notes on patriotism, discipline, religion, personal items, camp life; moderate interest. In Atlantic Monthly CXXXIV, 1924, pp 459-463. ANONYMOUS D163 1780 to 1784 Matthews: Diary; military service in Mysore; capture; sufferings as a prisoner of Hyder Ali at Seringapatam. 1. Journal of an Officer of Col. Baillie's Detachment London, 1788. 2. Captives of Tibu by A.W.Lawrence. London, 1929. 02/03 ANONYMOUS, probably British soldier *M1272,E A King's Mountain Diary edited by Mary Hardin McCown in East Tennessee Historical Society publications XIV, 1942, pp 102-105. 02 ANONYMOUS, young woman at Calcutta, using the pen name of Goldborne, or Goldsborn(e) (Annotation based upon extracts) From 1780? Letter journal in fictional framework, probably written retrospectively; it is not clear that this is based upon a contemporary record. 1. Hartly House, Calcutta 1789 and 1908. 2. Extract and discussion in A Various Universe by Ketaki Kushari Dyson. Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1978, pp 128-133. 01/02 ALLAIRE, Anthony [Lieut.] (1755-1838) of Fredericton, New Brunswick A143,M1273,E March to November 1780 Matthews: British military journal; campaign in South Carolina; battle of King's Mountain; personal and military details; good, lively narrative, with full entries. 1. King's Mountain and Its Heroes by Lyman C.Draper. New York, 1929, pp 484-515. 2. Extract in Tennessee Historical Quarterly VII, 1921, pp 104-106. 3. -

3-7Th FA Kicks Off NTC with a Bang

VOL. 35 NO. 19 | MAY 12, 2006 INSIDE 3-7th FA kicks off NTC with a bang Story and Photos by SPC. MIKE ALBERTS 3rd Brigade Public Affairs FORT IRWIN, Calif. – They fire big rounds, big distances. They are the Soldiers of 3rd Brigade, 7th Field Artillery Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, and they calibrated their big guns April 27 in preparation for enemy engagement at National Training Center. “Before we fire the guns in combat we need to calibrate them for the new lot of am- munition,” said Capt. Kevin Higgins, B Bat- RELATED STORIES Get more details of brigade training at Fort Irwin, Calif. See page A-6. Firefight for tery commander. “Every time we use a new lot of ammunition the guns need to be cal- ibrated. Basically, we shoot rounds through desert real estate each howitzer in order to get a velocity. “That figure is added to firing computa- 3rd Brigade Soldiers vie tions to ensure that our weapons hit targets accurately,” Higgins continued. “Each lot for control of insurgent [of ammunition] is slightly different, and it’s strongholds at NTC important for us to compensate for those differences in order to hit targets.” A-6 Brigade artillery brought its full comple- ment of 16 howitzers, also known as “M119A2,” to NTC. The unit is comprised of two firing batteries: A Battery and B Battery. Each battery is divided into two “sections.” Soldiers from Bravo Battery, 7th Field Artillery Regiment, 3rd Brigade, turn their faces and cover their ears over ear protection as a high- SEE GUNS, A-11 explosive artillery round shoots downrange during live-fire training at the National Training Center, Fort Irwin, Calif. -

Diaries 1831-1860

1831AD 03 ANONYMOUS - E 1831 “… the unnamed author … of this book travelled to Texas to take possession of some 20,000 acres he had purc hased in New York from the Galveston Bay Land Company. On arriving, however, instead of enjoying the wealth and prosperity he'd been promised, he learned that he'd been swindled by fast-talking speculators. But because he was immediately taken by the beauty and prospects of Texas, he stayed, and wrote this most valuable and informative record of pre- Republic times.” A Visit to Texas, Being the Journal of a Traveller through those parts Most interesting to American Settlers facsimile edition, Austin, Texas, Steck, 1952. 03 BARR, Amelia Edith Huddleston (1831-1919) British novelist and teacher, America immigrant - E Dates unknown All The Days of My Life: An Autobiography New York, Appleton, 1913, is reported to contain diary material. 03 BEALE, Dorothea (1831-1906) headmistress of Cheltenham Ladies’ College - E Dates unknown Dorothea Beale of Cheltenham by Elizabeth raikes, London, Constable, 1908, is reported to contain diary material. 01 BOURKE, Anne Maria December 6th. to 27th. 1831 Letter diary, written to her sister, of the daughter of the Governor of New South Wales; domestic and social life at Government House, Sydney; ceremonies; good descriptions; lively. In Life Lines: Australian women’s letters and diaries, 1788-1840 by Patricia Clarke and Dale Spender. St. Leonards, New South Wales, 1992, pp 74-77. BROWNING, Elizabeth Barrett (1806-1861) poet - H554 June 4th. 1831 to April 23rd. 1832 Personal diary of Elizabeth Barrett at Hope End. Intellectual, family and social life; her father; her health; anxiety about the financial problems which led to the sale of Hope End. -

Benjamin West, P.R.A

Weber, Kaylin Haverstock (2013) The studio and collection of the 'American Raphael': Benjamin West, P.R.A. (1738-1820). PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4307/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Studio and Art Collection of the ‘American Raphael’: Benjamin West, P.R.A. (1738-1820) Kaylin Haverstock Weber Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History of Art School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow January 2013 © Kaylin Haverstock Weber 2013 Abstract The Studio and Art Collection of the ‘American Raphael’: Benjamin West, P.R.A., 1738-1820 Kaylin Haverstock Weber When the history painter Benjamin West (1738-1820) died in March 1820, he left behind a remarkable monument to his life and work in his residence at 14 Newman Street, in London’s fashionable West End. Here, he had created an elaborate ‘palace’ of art, dedicated to history painting and to himself – his artistic genius, his artistic heroes, and his unique transatlantic identity. -

Handley Bib 4Ed V.III

Bibliography of Diaries Printed in English Index 229 1745AD 01 ANONYMOUS A42,M345 1745 Matthews (but not seen by him): Travel journal; "through several towns in the country, and to Boston again, in the winter past; containing many strange and remarkable occurrences. Which may be of singular advantage to the public if rightly improved in the present day. In the method of Mr. Whitfield's Journal, but vastly more entertaining." Journal of Travels Boston, 1745. 01 ANONYMOUS A42,M346 March to June 1745 Matthews: Military journal; from Boston to Louisburg and siege. In Louisburg Journals 1745 edited by L.E. de Forest. New York, 1932, pp 67-72. 01 ANONYMOUS, of Massachusetts contingent A42,M347 March to June 1745 Matthews: Military journal; siege of Louisburg. In Louisburg Journals 1745 edited by L.E. de Forest. New York, 1932, pp 73-79. 01 ANONYMOUS, of Second Massachusetts Regiment A42,M348 March to July 1745 Matthews: Military journal; from Charlestown to Louisburg; details of siege; interesting spellings and language, and doggerel verses. In Louisburg Journals 1745 edited by L.E. de Forest. New York, 1932, pp 80-96. 01 ANONYMOUS, of Fourth Massachusetts Regiment, probably of Springfield A42,M350 March to October 1745 Matthews: Military journal; siege of Louisburg; intelligent, detailed observation, and colloquial style. In Louisburg Journals 1745 edited by L.E. de Forest. New York, 1932, pp 1-54. 01 ANONYMOUS A42,M349 March to August 1745 Matthews: Sea journal; journal of sloop Union, Capt. Elisha Mayhew; expedition against Cape Breton; ship movements and engagements; interesting spellings. A Journal of the Voige in the Sloop Union edited by H.M.Chapin. -

Pacad286-All Access#7

Alicia Keys needs little introduction. The young singer/pianist’s first two albums—her 2001 debut, Songs in A Minor , and 2003’s The Diary of Alicia Keys — have together sold more than ten million copies, and her soulful pop R&B has won her nine GRAMMY ® Awards so far. , Having just returned home from a year and a half on the road, Alicia is currently preparing to record a new “unplugged” album at MTV’s studios to be released on MBKEntertainment/J Records. “It’s very exciting to go from one medium to the other,” she says. “This version of my live show was very thematic, very conceptual. And the unplugged project will be going back to my essence, just me and the piano in an acoustic set.” 22 yama ha all access summer ’05 23 “Yamahas have a nice balance between that strong, heavy weight and the fluidity of being ALICIA uSES A VARIETY OF YAMAHA PIANOS AND OTHER other songs I loved. But they didn’t come out good able to play smoothly.” keyboards, including the white 6’1” DC3 Disklavier at all. Conservatory Grand she played on her recent tour, I was trying to make them sound like somebody the C3NEO 6’1” Conservatory Collection Grand in else’s song so they would be good; and, therefore, her personal studio, and the very special purple piano they were bad! she keeps at home. I learned that when something really affects you, You began writing songs when you were very that’s when you write a good song.