Open Shellhamer Emma Theroleofthebookeditor.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions, Manuscripts & Letters, Presentation & Association Copies, Art & Illustrated Works, Film-Related Material, Etcetera. Catalogue 349 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. -

Raptis Rare Books Holiday 2017 Catalog

1 This holiday season, we invite you to browse a carefully curated selection of exceptional gifts. A rare book is a gift that will last a lifetime and carries within its pages a deep and meaningful significance to its recipient. We know that each person is unique and it is our aim to provide expertise and service to assist you in finding a gift that is a true reflection of the potential owner’s personality and passions. We offer free gift wrapping and ship worldwide to ensure that your thoughtful gift arrives beautifully packaged and presented. Beautiful custom protective clamshell boxes can be ordered for any book in half morocco leather, available in a wide variety of colors. You may also include a personal message or gift inscription. Gift Certificates are also available. Standard shipping is free on all domestic orders and worldwide orders over $500, excluding large sets. We also offer a wide range of rushed shipping options, including next day delivery, to ensure that your gift arrives on time. Please call, email, or visit our expert staff in our gallery location and allow us to assist you in choosing the perfect gift or in building your own personal library of fine and rare books. Raptis Rare Books | 226 Worth Avenue | Palm Beach, Florida 33480 561-508-3479 | [email protected] www.RaptisRareBooks.com Contents Holiday Selections ............................................................................................... 2 History & World Leaders...................................................................................12 -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC ARCHIVES & COLLECTIONS / RECENT ACQUISITIONS 15 Academy Street P. O. Box 668 Salisbury, CT 06068 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. [ANTHOLOGY] CUNARD, Nancy, compiler & contributor. Negro Anthology. 4to, illustrations, fold-out map, original brown linen over beveled boards, lettered and stamped in red, top edge stained brown. London: Published by Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co, 1934. First edition, first issue binding, of this landmark anthology. Nancy Cunard, an independently wealthy English heiress, edited Negro Anthology with her African-American lover, Henry Crowder, to whom she dedicated the anthology, and published it at her own expense in an edition of 1000 copies. Cunard’s seminal compendium of prose, poetry, and musical scores chiefly reflecting the black experience in the United States was a socially and politically radical expression of Cunard’s passionate activism, her devotion to civil rights and her vehement anti-fascism, which, not surprisingly given the times in which she lived, contributed to a communist bias that troubles some critics of Cunard and her anthology. Cunard’s account of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, published in 1932, provoked racist hate mail, some of which she published in the anthology. Among the 150 writers who contributed approximately 250 articles are W. E. B. Du Bois, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Brown, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Samuel Beckett, who translated a number of essays by French writers; Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, George Antheil, Ezra Pound, Theodore Dreiser, among many others. -

Literature, CO Dime Novels

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 991 CS 200 241 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Adolescent Literature, Adolescent Reading and the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 147p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 33813, $1.75 non-member, $1.65 member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v14 n3 Apr 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *English; English Curriculum; English Programs; Fiction; *Literature; *Reading Interests; Reading Material Selection; *Secondary Education; Teaching; Teenagers ABSTRACT This issue of the Arizona English Bulletin contains articles discussing literature that adolescents read and literature that they might be encouragedto read. Thus there are discussions both of literature specifically written for adolescents and the literature adolescents choose to read. The term adolescent is understood to include young people in grades five or six through ten or eleven. The articles are written by high school, college, and university teachers and discuss adolescent literature in general (e.g., Geraldine E. LaRoque's "A Bright and Promising Future for Adolescent Literature"), particular types of this literature (e.g., Nicholas J. Karolides' "Focus on Black Adolescents"), and particular books, (e.g., Beverly Haley's "'The Pigman'- -Use It1"). Also included is an extensive list of current books and articles on adolescent literature, adolescents' reading interests, and how these books relate to the teaching of English..The bibliography is divided into (1) general bibliographies,(2) histories and criticism of adolescent literature, CO dime novels, (4) adolescent literature before 1940, (5) reading interest studies, (6) modern adolescent literature, (7) adolescent books in the schools, and (8) comments about young people's reading. -

Oak Knoll Books

OAK KNOLL spring SALE LARGE DISCOUNTS ON Antiquarian & Publishing BOOKS ABOUT BOOKS 1-4 BOOKS 20% OFF 5-9 BOOKS 30% OFF 10-25 BOOKS 40% OFF 26-99 BOOKS 45% OFF 100+ BOOKS 50% OFF CATALOGUE M562 Titles may be combined for discount. Thus, by ordering one copy each of five differ- ent titles you will receive a 30% discount. This applies equally to the trade as well as to our private and library customers. We have multiple copies of some of these items, so if interested, please ask. All books are subject to prior sale and must be ordered at the same time. These discounts will only be offered through JULY 15, 2009. For mailing within the United States please add $7.50 for the first book and $1.00 for each additional volume. Canada- First item $8.00, additional items by weight and ser- vice. All other- First item $9.00, additional items by weight and service. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and Discover. Orders are regularly shipped within seven working days of their receipt. OAK KNOLL BOOKS . 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720, USA Phone: 1-(800) 996-2556 . Fax: (302) 328-7274 [email protected] . www.oakknoll.com ANTIQUARIAN 1. (Abbey, J.R.) CATALOGUE OF HIGHLY IMPORTANT MODERN FRENCH ILLUSTRATED BOOKS AND BINDINGS FORMING PART V OF THE CELEBRATED LIBRARY OF THE LATE MAJOR J.R. ABBEY. London: Sotheby & Co., 1970, small 4to., stiff paper wrappers. 179 pages. $ 55.00 S-K 1184. Foldout frontispiece and 62 other full-page plates. Some plates in color. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

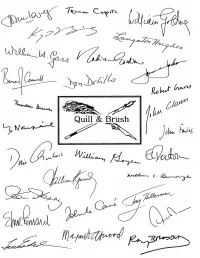

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

Race, Genre and Commodification in the Detective Fiction of Chester Himes

Pulping the Black Atlantic: Race, Genre and Commodification in the Detective Fiction of Chester Himes A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 William Turner School of Arts, Histories and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………... 3 Declaration/Copyright……………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction: Chester Himes’s Harlem and the Politics of Potboiling…………………………. 6 Part One: Noir Atlantic 1. ‘I felt like a man without a country.’: Himes’s American Dilemma …………………………………………………….41 2. ‘What else can a black writer write about but being black?’: Himes’s Paradoxical Exile……………………………………………………….58 3. ‘Naturally, the Negro.’: Himes and the Noir Formula……………………………………………………..77 Part Two: ‘The crossroads of Black America.’ 4. ‘Stick in a hand and draw back a nub.’: The Aesthetics of Urban Pathology in Himes’s Harlem……………………….... 96 5. ‘If trouble was money…’: Harlem’s Hustling Ethic and the Politics of Commodification…………………116 6. ‘That’s how you got to look like Frankenstein’s Monster.’: Divided Detectives, Authorial Schisms………………………………………... 135 Part Three: Pulping the Black Aesthetic 7. ‘I became famous in a petit kind of way.’: American (Mis)recognition…………………………………………………….. 154 8. ‘That don’t make sense.’: Writing a Revolution Without a Plot…………………………………………… 175 Conclusion: Of Pulp and Protest……………………………………………………………...194 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………. 201 Word count: 85,936 3 Abstract The career path of African American novelist Chester Himes is often characterised as a u-turn. Himes grew to recognition in the 1940s as a writer of the Popular Front, and a pioneer of the era’s black ‘protest’ fiction. However, after falling out of domestic favour in the early 1950s, Himes emigrated to Paris, where he would go on to publish eight Harlem-set detective novels (1957-1969) for Gallimard’s La Série Noire. -

The Bestseller and the Blockbuster Mentality

The Bestseller and the Blockbuster Mentality McGowan, P. (2018). The Bestseller and the Blockbuster Mentality. In K. Curnutt (Ed.), American Literature in Transition, 1970-80 (pp. 210-225). (American Literature in Transition). Cambridge University Press. Published in: American Literature in Transition, 1970-80 Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 Cambridge University Press. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:26. Sep. 2021 Chapter Twelve: The Bestseller and the Blockbuster Mentality Philip McGowan The 1970s was a decade of important cultural and literary interest in the history of the United States for manifold reasons: aside from the first attempted impeachment of a president in over a century, and the celebration of the nation’s bicentennial marked by events that ran from April 1975 to July 4, 1976, the American literary world underwent a transition of irrevocable proportions. -

T H E C O L O P H O N B O O K S H

T H E C O L O P H O N B O O K S H O P Robert and Christine Liska P. O. B O X 1 0 5 2 E X E T E R N E W H A M P S H I R E 0 3 8 3 3 ( 6 0 3 ) 7 7 2 8 4 4 3 List 228 Books about Books * Literature * Miscellaneous All items listed have been carefully described and are in fine collector’s condition unless otherwise noted. All are sold on an approval basis and any purchase may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Member ABAA and ILAB. All items are offered subject to prior sale. Please add $4.00 shipping for the first book, $1.00 for each additional volume. New clients are requested to send remittance with order. All shipments outside the United States will be charged shipping at cost. We accept VISA, MASTERCARD and AMERICAN EXPRESS. (603) 772-8443; FAX (603) 772-3384; e-mail: [email protected] Please visit our web site to view additional images and titles. http://www.colophonbooks.com If you find something of interest from this List or on our website, please do not order it through one of the third party online databases. They charge a fee for placing that order using their shopping cart. Our shopping cart is secure, or, you can always give us a call. ☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼☼ “Next to talking about books comes the pleasure of reading them, especially books about books. This is an extra category I would recommend to collectors. -

Howard Fast, James T. Farrell, and the Best Short Stories of Theodore Dreiser

Howard Fast, James T. Farrell, and The Best Short Stories of Theodore Dreiser JOSEPH GRIFFIN, University of Ottawa Shortly after Theodore Dreiser's death, the World Publishing Company was granted publication rights to Dreiser's works by his widow Helen.1 World's first project under this arrangement was a volume of Dreiser's best short fiction, and the editors hired Howard Fast to make a selection of stories and to write an intro duction. The Best Short Stories of Theodore Dreiser, a fourteen-piece collection, ap peared in 1947 with Fast's highly laudatory introduction. Nine years later World reissued the book, discarding the Fast introduction and commissioning James T. Farrell to write a new one. These events constitute what Fast calls "an interesting story,"2 and the story deserves telling at the very least in the interest of shedding light on a small corner of Drieseriana that has gone unnoticed. Fast took to the World assignment with enthusiasm. A frequent contributor to the Communist magazine New Masses, he was a fervent admirer of Dreiser's fiction and saw Dreiser's joining the Communist party as evidence that he must be read as a proletarian fictionist. Fast sent to Dreiser's widow for the short story collections;3 chose four stories from Free and Other Stories, eight stories from Chains, and two sketches from Twelve Men;* and wrote a glowing essay placing Dreiser at the very zenith of American short-story writers. The essay performed double duty: several months before The Best Short Stories appeared, Fast published it in the September 3, 1946 issue of New Masses; when the volume appeared the following March, he used the essay, in a somewhat modified form, as the introduction. -

Arkham House Archive Calendar

ARKHAM HOUSE ARCHIVE CALENDAR ARKHAM HOUSE ARCHIVE SALE DOCUMENTS 4 typewritten letters dated 25 May 2010, 25 October 2010, 15 January 2011, and 26 January 2011, each signed by April Derleth, conveying the archive, "books, letters, manuscripts, contracts, Arkham House ephemera & items" (including "personal items as well as items from my business" and "all remaining items in the basement") to David H. Rajchel, "to take & deal with as he sees fit." Accompanied by a bill of sale dated 17 March 2011, prepared by Viney & Viney, Attorneys, Baraboo, WI (typed on the verso of a 1997 State of Wisconsin Domestic Corporation Annual Report for Arkham House Publishers, Inc.). Additionally, there is a bill of sale for the Clark Ashton Smith papers and books sold to David H. Rajchel, signed by April Derleth. ARKHAM HOUSE ORDERS Book Orders and Related Correspondence, mostly 1960s. ARKHAM HOUSE ROYALTY STATEMENTS Large file of royalty payment statements, mostly between 1 September 1959 and 1 September 1967. Extensive, but not complete. Includes some summaries. There are a few statements from 1946 and 1952 (Long) and 1950-1959 (all Whitehead). Also, sales figures for 1 July 1946 through 1 January 1947 [i.e. 31 December 1946] and 1 July 1963 through 31 December 1966. Some Arkham House correspondence regarding accounting and royalties paid by Arkham House to their authors is filed here. BOOK PRODUCTION Production material for Arkham House, Mycroft & Moran, or Stanton & Lee publications, as well as books written or edited by Derleth which were published by others. This material is organized by author/editor and book title. -

BOOKS on BOOKS Catalog 719

R & A PETRILLA Antiquarian booksellers and appraisers since 1970. [email protected] www.petrillabooks.com BOOKS ON BOOKS Catalog 719 Prices include shipping in the US. Shipping overseas is at cost. All items are guaranteed as described, and we always appreciate your orders. – Bob & Alison ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. Abbey, J.R. SCENERY OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND IN AQUATINT AND LITHOGRAPHY, 1770-1860, FROM THE LIBRARY OF J.R. ABBEY. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1991. Reprint. ISBN: 1-55660-130-1. pp: xx, 399; frontispiece in color, 34 collotype plates and 54 text illustrations in black & white. Bound in red leatherette, gilt-stamped spine, decorated dust wrapper. 12.5" X 9" Fine in Fine dust-jacket. Hardcover. (#040840) $175.00 2. Abbey, J.R. TRAVEL IN AQUATINT AND LITHOGRAPHY, 1770-1860: From the Library of J.R. Abbey. Volume I: World, Europe, Africa. Volume II: Asia, Oceanica, Antarctica, America. A Bibliographical Catalogue. London / Mansfield, CT: Curwen Press / Maurizio Martino, 1956 / nd. Reprint. Two volumes bound as one. pp: xiii, 675 with indices; black-and-white frontispiece and illustrations from title=pages, etc. Bound in gray cloth, red spine block with gilt lettering. 11.25" x 8.5" Fine. Hardcover. "This reprint is strictly limited to 100 copies" (statement on verso title-page). (#040783) $110.00 3. Adamic, Louis / Christian, Henry A. LOUIS ADAMIC: A CHECKLIST. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, (1971). First Edition. pp: xlvii, 164 with index. Bound in green cloth, black spine lettering. 8.75" x 5.5" Very Good. Hardcover. Has a detailed introduction on Adamic's background and work.