Historic District & Landmark Design Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tompkins County HM Final Draft 01-16-14.Pdf

This Multi-Jurisdictional All-Hazard Mitigation Plan Update has been completed by Barton & Loguidice, P.C., under the direction and support of the Tompkins County Planning Department. All jurisdictions within the County participated in this update process. A special thanks to the representatives and various project team members, whose countless time and effort on this project was instrumental in putting together a concise and meaningful document. Tompkins County Planning Department 121 East Court Street Ithaca, New York 14850 Tompkins County Department of Emergency Response Emergency Response Center 92 Brown Road Ithaca, New York 14850 Tompkins County Multi-Jurisdictional All-Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 1.1 Background ..............................................................................................................3 1.2 Plan Purpose.............................................................................................................4 1.3 Planning Participants ...............................................................................................6 1.4 Hazard Mitigation Planning Process ........................................................................8 2.0 Tompkins County Profile ..................................................................................................9 -

32026062-MIT.Pdf

K.'-.- A, N E W Q UA D R A N G L E F O R C O R N E L L U N I V E R S I T Y A Thesis.submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement s for the degree of Master of Architec ture at the Massachusetts Inst itute of Technology August 15, 1957 Dean Pie tro Bel lus ch Dean of the School of Archi tecture and P lanning Professor000..eO0 Lawrence*e. *90; * 9B. Anderson Head oythe Departmen ty6 Arc,hi tecture Earl Robert"'F a's burgh Bachelor of Architecture, Cornell University,9 June 1954 323 Westgate West Cambridge 39, Mass. August 14, 1957 Dean Pietro Belluschi School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge 39, Massachusetts Dear De-an Belluschi, In partial fulfillment- of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture, I should like to submitimy thesis entitled, "A New Quad- rangle for Cornell University". Sincer y yours, -"!> / /Z /-7xIe~ Earl Robert Fla'nsburgh gr11 D E D I C A T I O N To my wife, Polly A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S The development of this thesis has been aided by many members of the s taff at both M.I.T. &nd Cornell University. W ithou t their able guidance and generous assistance this t hesis would not have been possible. I would li ke to take this opportunity to acknowledge the help of the following: At M. I. T. -

Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White</H1>

Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Scanned by Charles Keller with OmniPage Professional OCR software Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White Volume II Scanned by Charles Keller with OmniPage Professional OCR software donated by Caere Corporation, 1-800-535-7226. Contact Mike Lough AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDREW DICKSON WHITE WITH PORTRAITS VOLUME I page 1 / 895 NEW YORK THE CENTURY CO. 1905 Copyright, 1904, 1905, by THE CENTURY CO. ---- Published March, 1905 THE DE VINNE PRESS TO MY OLD STUDENTS THIS RECORD OF MY LIFE IS INSCRIBED WITH MOST KINDLY RECOLLECTIONS AND BEST WISHES TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I--ENVIRONMENT AND EDUCATION CHAPTER I. BOYHOOD IN CENTRAL NEW YORK--1832-1850 The ``Military Tract'' of New York. A settlement on the headwaters of the Susquehanna. Arrival of my grandfathers and page 2 / 895 grandmothers. Growth of the new settlement. First recollections of it. General character of my environment. My father and mother. Cortland Academy. Its twofold effect upon me. First schooling. Methods in primary studies. Physical education. Removal to Syracuse. The Syracuse Academy. Joseph Allen and Professor Root; their influence; moral side of the education thus obtained. General education outside the school. Removal to a ``classical school''; a catastrophe. James W. Hoyt and his influence. My early love for classical studies. Discovery of Scott's novels. ``The Gallery of British Artists.'' Effect of sundry conventions, public meetings, and lectures. Am sent to Geneva College; treatment of faculty by students. A ``Second Adventist'' meeting; Howell and Clark; my first meeting with Judge Folger. Philosophy of student dissipation at that place and time. -

UC Santa Barbara Other Recent Work

UC Santa Barbara Other Recent Work Title Geopolitics, History, and International Relations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/29z457nf Author Robinson, William I. Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CONTEMPORARY SCIENCE ASSOCIATION • NEW YORK Geopolitics, History, and International Relations VOLUME 1(2) • 2009 ADDLETON ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS • NEW YORK Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 1(2) 2009 An international peer-reviewed academic journal Copyright © 2009 by the Contemporary Science Association, New York Geopolitics, History, and International Relations seeks to explore the theoretical implications of contemporary geopolitics with particular reference to territorial problems and issues of state sovereignty, and publishes papers on contemporary world politics and the global political economy from a variety of methodologies and approaches. Interdisciplinary and wide-ranging in scope, Geopolitics, History, and International Relations also provides a forum for discussion on the latest developments in the theory of international relations and aims to promote an understanding of the breadth, depth and policy relevance of international history. Its purpose is to stimulate and disseminate theory-aware research and scholarship in international relations throughout the international academic community. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations offers important original contributions by outstanding scholars and has the potential to become one of the leading journals in the field, embracing all aspects of the history of relations between states and societies. Journal ranking: A on a seven-point scale (A+, A, B+, B, C+, C, D). Geopolitics, History, and International Relations is published twice a year by Addleton Academic Publishers, 30-18 50th Street, Woodside, New York, 11377. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) Washington State Library Thurston County, WA Name of Property County and State United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Washington State Library other names/site number Joel M. Pritchard Building 2. Location th street and 415 15 Avenue Southeast not for publication number city or town Olympia vicinity state Washington code WA county Thurston code 067 zip code 98501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: local Applicable National Register Criteria A C Signature of certifying official/Title Date WASHINGTON SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Cornell Alumni News

Cornell Alumni News Volume 46, Number 22 May I 5, I 944 Price 20 Cents Ezra Cornell at Age of Twenty-one (See First Page Inside) Class Reunions Will 25e Different This Year! While the War lasts, Bonded Reunions will take the place of the usual class pilgrimages to Ithaca in June. But when the War is won, all Classes will come back to register again in Barton Hall for a mammoth Victory Homecoming and to celebrate Cornell's Seventy-fifth Anniversary. Help Your Class Celebrate Its Bonded Reunion The Plan is Simple—Instead of coming to your Class Reunion in Ithaca this June, use the money your trip would cost to purchase Series F War Savings Bonds in the name of "Cornell University, A Corporation, Ithaca, N. Y." Series F Bonds of $25 denomination cost $18.50 at any bank or post office. The Bonds you send will be credited to your Class in the 1943-44 Alumni Fund, which closes June 30. They will release cash to help Cornell through the difficult war year ahead. By your participation in Bonded Reunions: America's War Effort Is Speeded Cornell's War Effort Is Aided Transportation Loads Are Eased Campus Facilities ^re Saved Your Class Fund Is Increased Cornell's War-to-peace Conversion Your Money Does Double Duty Is Assured Send your Bonded Reunion War Bonds to Cornell Alumni Fund Council, 3 East Avenue, Ithaca, N. Y. Cornell Association of Class Secretaries Please mention the CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Volume 46, Number 22 May 15, 1944 Price, 20 Cents CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Subscription price $4 a year. -

Deep Springs Newsletter Fall 2011 Visiting Professors

DEEP SPRINGS NEWSLETTER FALL 2011 VISITING PROFESSORS Sam Laney and dynamics of marine photosynthetic microbes. Dur- Sam Laney DS87 returned to the valley in August ing his intervening time “on shore” he pursues his other to teach both a standard course in Differential Calculus research interests in marine microbial ecology and leads and an advanced course in Multivariable Calculus, having graduate courses in his institution’s joint program with taught computer science and mathematics at Deep Springs MIT. before, in 2007. Sam fits naturally into the Deep Springs project, Sam grew up in a small paper-mill town on the riding on the occasional cattle drive or with students on Kennebec River in central Maine. After high school he weekends. He says that spent two years at Deep Springs (1987-89) before continu- one of the great lessons ing his studies at Cornell University. Sam lived at Telluride he gained from Deep Association’s Cornell Branch, serving twice as house presi- Springs was the ability dent, where he was able to maintain his interest in Nunnian to take two interests— education while completing a joint degree in Engineer- one intellectual, and ing and Biology. He then worked at the Department of one practical—and Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, unite them to build a developing and field-testing technology for monitoring the life and career. “On health of oceanic microorganisms. Later he worked in the the one hand you’re ocean instrumentation industry in both the US and UK, dealing with ecologi- and subsequently went back to graduate school at Oregon cal theory of marine State University, where he earned a Ph.D. -

Tompkins County Public Library Assigned Branch: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library (TCPL) Collection: Local History (LH)

TOMPKINS COUNTY Navigating A Sea Of Resources PUBLIC LIBRARY Title: The first hundred years : a history of the Cornell Public Library, Ithaca, New York, and the Cornell Library Association, 1864-1964. Author: Call number: LH-CASE 027.409 Peer Publisher: [Ithaca, N.Y.?] : [s.n.] 1969. Owner: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library Assigned Branch: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library (TCPL) Collection: Local History (LH) Material type: Book Number of pages: 1 30 pages THE FIRST HUNDRED YEARS A HISTORY OF THE CORNELL PUBLIC LIBRARY Ithaca, New York and the CORNELL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 1864 - 1964 by Sherman Peer THE AUTHOR It's good to think of the new library so well organized and increasing in service. I am happy to have lived to see it functioning fully and so well received by the people of Tompkins County. Letter from Sherman Peer, dated February 2?, 19^9, to Mrs. John Vandervort, chairman of the trustees of the Tompkins County Public Library. Sherman Peer searched the records of the Cornell Library Association, many other written sources, and his own rich memories to write this history. A prominent Ithaca attorney who enjoyed writing and story-telling, Mr. Peer completed his work on it in 1964, when he was 81 years old. The epilogue was written by Mary Tibbets Freeman, and the manuscript was prepared for presentation at the formal dedication of the Tompkins County Library Building on April 20, 19&9. The historian also shaped the library's history by assisting in its successful rebirth as a public institution in its second century. He was convinced that the Cornell Public Library, operated since 1866 by the private Cornell Library Associa tion founded by Ezra Cornell, needed public funds for a new building and continuing support. -

Biodiversity Education Initiative for Middle School Students Meryl Gray Hunter Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects December 2004 Biodiversity Education Initiative for Middle School Students Meryl Gray Hunter Worcester Polytechnic Institute Peter J. Vallieres Worcester Polytechnic Institute Vincent Joseph Papia Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Gray Hunter, M., Vallieres, P. J., & Papia, V. J. (2004). Biodiversity Education Initiative for Middle School Students. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/3056 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuesday December 14, 2004 Mr. Francisco Dallmeier, Director Mr. Alfonso Alonso, Assistant Director Ms. Jennifer Sevin, Education and Training Coordinator Monitoring and Assessment of Biodiversity Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 Dear Mr. Dallmeier, Mr. Alonso, and Ms. Sevin, Enclosed is our report entitled Biodiversity Education Initiative for Middle School Students. It was written at the Smithsonian Institution, Monitoring and Assessment of Biodiversity during the period of October 29 through December 14, 2004. Preliminary work was completed in Worcester, Massachusetts, prior to our arrival in Washington, D.C. -

Campus Landscape Notebook

CAMPUS LANDSCAPE NOTEBOOK Campus Planning Office May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Campus Landscape Notebook, 2005, was produced in the Cornell Campus Planning Office under the direction of the University Planner, Minakshi Amundsen. John Ullberg, Landscape Architect, composed text, provided photographs and many graphics. Illiana Ivanova, graphic designer, composed and formatted content and created graphics as well. Andrew Eastlick produced campus base maps. Craig Eagleson provided both technical support and graphic advice. Many others have contributed to the project by editing, researching and advising. Among them are Laurene Gilbert, Ian Colgan, Jim Constantin, Dennis Osika, Frank Popowitch, Peter Karp, Don Rakow, Helen Baker, Craig Eagleson, Phil Cox, Jim Gibbs and Kent Hubbell. Photo Credits p2- Libe Slope White Oak- Robert Barker, Cornell University Photography p5- Aerial view of campus- Kucera International, Inc. All other aerial views except otherwise noted- Jon Reis (www.jonreis.com) CAMPUS LANDSCAPE NOTEBOOK INTRODUCTION S E C T I O N 1 THE CAMPUS LANDSCAPE, PAST TO PRESENT ORIGINS. 9 HISTORY AND EVOLUTION. 11 CHRONOLOGY . 21 FUTURE . 23 THE CAMPUS EXPERIENCE . 25 S E C T I O N 2 LANDSCAPE SYSTEMS AT CORNELL PHYSIOGRAPHY . 31 THE OPEN SPACE SYSTEM . .33 THE WORKING LANDSCAPE. .35 LINKS. .37 GEOMETRY. 39 ARCHITECTURE. .41 WAYFINDING. .45 VIEWS. 47 LANDSCAPE VOCABULARY. 49 LANDMARKS. .55 SUMMARY. .59 INTRODUCTION Landscape has meaning. The quality and meaning of the living and learning experience at Cornell are fundamentally related to the quality of the campus environment. For six years a political prisoner of the communist By any measure Cornell’s is a remarkable landscape - deep wild gorges, government in Laos, the former Laotian official said lakes, cascades, noble buildings set among noble trees, expansive views he was sustained by memories of Cornell Univer- all contribute to a special presence that sets Cornell apart from its peers. -

Campus Map a K L Ar E Th P L R D T No C E En E Riv N X R D a I Od Hl a L O Cornell Buildings

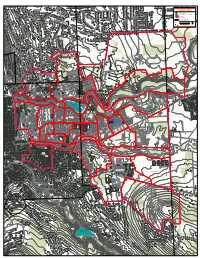

E V I R D N O T E E E V R I T W REMINGTON ROAD R S D N I E T W T N TUARY DRIVE I OUR E NC A SA E E R SIMSBURY DRIV W R E Y T Y D S T N O L A E N R I B R D U R I M SPRUCE LANE V E MEADOWLANERK ROAD T HE ETOPHER LANE P CHRISTRE AR KW A NE Y CAMPUS MAP A K L AR E TH P L R D T NO C E EN E RIV N X R D A I OD HL A L O CORNELL BUILDINGS C W S I H G I S RC H N BI L R E A WOOD DRIV A BIRCH E N L D E A H A N P E O O S T R I N E BUILDINGS OF OTHER DESIGNATION E X T N O E R N N R B E I A P T L L H S D A I A N R R H M E A I H M V P M C ADINAL DRIVE C CARO T E O K N COMSTREETOCK ROAD E CMP ZONES RO R S A T D R R O E E A C E D A T MORE DRIVE L O SYCA P CMP PRECINCTS N D E O E A V A PLACE O S I LI V E W E R N E IV D 2566 R U D N MUNICIPAL BOUNDARIES I D Rhodes House T E ROCKY LANE E P E O R SA T I O ES N T W OR C F AT MA R 20' TOPOGRAPHIC CONTOURS H NO A R I H E STR I R E R G IN ET H E B L C A IR C N LE RIVE E MAPLACEEWOOD D N D 0 250 500 750 R O A D Feet N O R T H E V I R © Campus Planning Office D January 2014 M E OAD L R A ODS BIRCHWOOD DRIVE O S W T KLINE E E Robin Hill Carriage House R T S Y KAY STREET SPUR A K M C I D E A C Y A W N Y U A A U L G Y G A R H R AN Robin Hill A E S H O H HANSHAW ROAD AW P R E A M D O 2514 A AD I D M A G R A O H K H R T R P S I D O R R N A O T A D L A P D U T S A E F O R R E E C S H E CIR B A RK L R R PA A O C D A A K D S G A S U T T Y R O A C C E N E D E T A A O A R AY V H HW E RT N Dyce Lab NO T U Storage I W E E AT STREET S RO 2810E T U P L Dyce Lab A F N Garage D O Dyce Lab R O 2810A A Garden Shed D 2810N Dyce Lab -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project ELEANOR LOPES “PENNY” AKAHLOUN Interviewed by: Daniel F. Whitman Initial interview date: July 19, 2008 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS MY FORMATIVE YEARS, 1943–1965 Born and raised in Onset, Massachusetts Cape Verdean History and Whaling Ships The Schooner Ernestina and the Packet Trade Small, Round, and Copper Tone Harsh Life for Cape Verdeans on the Cranberry Bogs Vera Cruz VII Shipwreck at Ocracoke, North Carolina Rescue of the Passengers Grandfather’s Marriage and the Curse Oak Grove School Prejudice and “Jungletown” My Big Dream at Age 8 Moving from Cape Cod to Boston, Massachusetts No Vacancy at Bethany Union If First You Don’t Succeed, Try and Try Again Massachusetts Attorney General Edward W. Brooke and a Second Chance Joining the Foreign Service THE PHILIPPINES, 1965–1967 1 The Right Place at the Right Time Shooting the Rapids at Pagsanjan Falls, Laguna Electric Typewriters, Carbons and Pencil Erasers Vice President Hubert Humphrey Attends President Ferdinand Marcos’ 1965 Inauguration Bike Rides on the Island of Mindanao Holy Week in Bongabong, Oriental Mindoro The Eclipse of Sukarno and the Rise of Suharto Bombs Rain Down on Saigon Skies President Lyndon Johnson and the Seven-Nation Manila Summit U.S. -Philippine Relations Around the World and Home in One Piece WASHINGTON, DC, AND HOME LEAVE, LATE 1967 Reverse Cultural Shock Vietnam War Demonstrations MOROCCO, 1968–1970 The Moroccan Treaty of Friendship, the Longest Unbroken Accord in U.S. History Disappearance of Mehdi Ben Barka U.S.-Moroccan Relations Marrakech’s Djema El Fna Square and Snake Charmers A Sense of Being Home A Muslim and a Christian Fall in Love The State Department’s Historical 1972 Directive Permission Granted to Marry a U.S.