PDF (Accepted Manuscript)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Post-War Immigration Issues According to Italian-Language Newspaper Il Globo, 1959 - 1969

Australian Post-war immigration issues according to Italian-language newspaper Il Globo, 1959 - 1969 Submitted by Brent Russell Thomas Edwards Supervisor: Dr. Simone Battiston A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Business Honours Faculty of Business and Enterprise Swinburne University of Technology Hawthorn, Victoria November 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank the following people, without whom, this thesis would not have been produced: Firstly, I would like to express gratitude to my supervisor Simone Battiston, for his patience and encouragement, and for his insight on post-war Italian-Australian studies which assisted greatly to conceptualise the issues addressed in this thesis. I would also like to thank Sharon Grant for her invaluable advice and time dedicated toward the thesis, particularly with the literature review and research methodology. Additional acknowledgements go to Bruno Mascitelli for his supplementary insight to the topic, time dedicated to brainstorming and assistance in obtaining references. I would like to express particular gratitude to Il Globo Director Ubaldo Larobina and Anna Trabucco, who showed me every kindness and granted access to the newspaper’s archives in North Fitzroy, Melbourne. 1 Declaration This thesis contains no material accepted toward any other degree, diploma or similar award, in any university or institution and that, to the best of my knowledge, the thesis contains no material published or written by another person, except where due reference is made -

The Cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele

WHO IS BEHIND THE CAMERA? The cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele Silvana Tuccio Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2009 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Who is behind the camera? Abstract The cinema of independent film director Giorgio Mangiamele has remained in the shadows of Australian film history since the 1960s when he produced a remarkable body of films, including the feature film Clay, which was invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1965. This thesis explores the silence that surrounds Mangiamele’s films. His oeuvre is characterised by a specific poetic vision that worked to make tangible a social reality arising out of the impact with foreignness—a foreign society, a foreign country. This thesis analyses the concept of the foreigner as a dominant feature in the development of a cinematic language, and the extent to which the foreigner as outsider intersects with the cinematic process. Each of Giorgio Mangiamele’s films depicts a sharp and sensitive picture of the dislocated figure, the foreigner apprehending the oppressive and silencing forces that surround his being whilst dealing with a new environment; at the same time the urban landscape of inner suburban Melbourne and the natural Australian landscape are recreated in the films. As well as the international recognition given to Clay, Mangiamele’s short films The Spag and Ninety-Nine Percent won Australian Film Institute awards. Giorgio Mangiamele’s films are particularly noted for their style. This thesis explores the cinematic aesthetic, visual style and language of the films. -

Annual Report 2019 Annual Report2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ANNUAL REPORT2019 CONTENTS 2 2 2 3 36 38 40 42 Vision Mission Aims Overview Article: ‘Bright white National Priority Case Article: The Great Graduate and Early skeletons’: some Study: Great Barrier Barrier Reef outlook is Career Training Western Australian Reef Governance ‘very poor’. We have one reefs have the lowest last chance to save it coral cover on record 5 6 8 9 51 52 56 62 Director’s Report Research Impact and Recognition of 2019 Australian Graduate Profile: Article: “You easily National and Communications, Media Engagement Excellence of Centre Research Council Emmanuel Mbaru feel helpless and International Linkages and Public Outreach Researchers Fellowships overwhelmed”: What it’s like being a young person studying the Great Barrier Reef 10 16 17 18 66 69 73 87 Research Program 1: Researcher Profile: Article: The Cure to Research Program 2: Governance Membership Publications 2020 Activity Plan People and Ecosystems Danika Kleiber the Tragedy of the Ecosystem Dynamics, Commons? Cooperation Past, Present and Future 24 26 28 34 88 89 90 92 Researcher Profile: Article: The Great Research Program 3: Researcher Profile: Ove Financial Statement Financial Outlook Key Performance Acknowledgements Yves-Marie Bozec Barrier Reef was seen a Responding to a Hoegh-Guldberg Indicators ‘too big to fail.’ A study Changing World suggests it isn’t. At the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies we acknowledge the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of this nation. We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and sea where we conduct our business. We pay our respects to ancestors and Elders, past, present and future. -

Recent Italian-Australian Narrative Fiction by First Generation Writers

Kunapipi Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 9 2009 Recent Italian-Australian narrative Fiction by first generation writers Gaetano Rando Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Rando, Gaetano, Recent Italian-Australian narrative Fiction by first generation writers, Kunapipi, 31(1), 2009. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol31/iss1/9 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Recent Italian-Australian narrative Fiction by first generation writers Abstract The publication in 2008 of the English version of Emilio Gabbrielli’s (2000) novel Polenta e Goanna and the new re-introduced edition of Rosa Cappiello’s Oh Lucky Country in 2009 constitutes something of a landmark in Italian- Australian writing. Cappiello’s novel is now the second most-published work by a first generation Italian-Australian writer after Raffaello Carboni’s (1855) Eureka Stockade. Although Italians in Australia have been writing about their experiences since the mid 1800s and have produced texts such as those by Salvado (1851), Ercole (1932) and Nibbi (1937), a coherent corpus of Italian-Australian writing has developed only after the post-World War Two migration boom which saw some 360,000 Italian-born migrants entering Australia between 1947 and 1972. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol31/iss1/9 100 Gaetano RANDO Recent Italian-Australian Narrative Fiction by First Generation Writers The publication in 2008 of the English version of Emilio Gabbrielli’s (2000) novel Polenta e Goanna and the new re-introduced edition of Rosa Cappiello’s Oh Lucky Country in 2009 constitutes something of a landmark in Italian- Australian writing. -

A History of Italian Food in Australia with Case Studies

Ideas of Italy and the Nature of Ethnicity: A History of Italian Food in Australia with Case Studies Tania Cammarano Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of History School of Humanities University of Adelaide January 2018 Included Publications _______________________________________________________ 5 Abstract _________________________________________________________________ 6 Thesis Declaration _________________________________________________________ 8 Acknowledgements ________________________________________________________ 9 Introduction _____________________________________________________________ 11 Literature Review ________________________________________________________________ 20 Methodology ___________________________________________________________________ 32 Imagining Italy in Australia _________________________________________________________ 36 Romantic Italy ___________________________________________________________________ 37 Glamorous Italy _________________________________________________________________ 40 Attitudes Towards Italian Migrants __________________________________________________ 47 Italian Ethnicity as a Resource ______________________________________________________ 59 Overview of Thesis Structure _______________________________________________________ 61 Statement of Authorship for Chapter One _____________________________________ 66 Chapter One: Leggo’s not-so-Autentico: Invention and Representation in 20th Century Italo-Australian Foodways __________________________________________________ -

Presentation Title

Accessing Culturally Appropriate Resources for your Consumers Webinar 27th April 2021 Acknowledgment of Country We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the Land where ever this webinar takes place. We would like to pay respect to the Elders past, present and emerging. Policy Framework “Older people have easily accessible information about the aged care system and services that they understand, and find the information helpful to exercise choice and control over the care they receive”. The Aged Care Diversity Framework (Department of Health, 2017) Who we are PICAC Alliance (The Alliance) is a unified national body comprising of each state and territory specific Partners in Culturally Appropriate Care (PICAC) funded organisations. The Alliance aims to be a voice and discussion conduit into information, training and resources to inform aged and community care services of today and tomorrow. www.picacalliance.org Our members: VICTORIA Lisa Tribuzio Manager Centre for Cultural Diversity in Ageing PICAC Vic Top 10 birthplaces Non English Speaking Background 65+ in Victoria 1. Italy 2. Greece 3. Germany 4. Netherlands 5. China 6. Malta 7. India 8. Vietnam 9. Croatia 10. Poland • Nfd = not further defined *2016 Census Centre for Cultural Diversity in Ageing website www.culturaldiversity.com.au Multilingual Resources for Aged Care Providers Resource Languages Communication Cards 57 Aged Care Signage 57 Consumer Feedback Form 12 Interpreter Cards 32 Available at http://www.culturaldiversity.com.au/service-providers/multilingual-resources Multilingual Communication Cards Depict a wide range of daily activities and situations and can be used to prompt discussion, assist with directions, clarify a client’s needs. -

History and Collective Memory of the Italian Migrant Workers’ Organisation FILEF in 1970S Melbourne

History and Collective Memory of the Italian Migrant Workers’ Organisation FILEF in 1970s Melbourne Submitted by Simone Battiston (Dott. Storia, University of Trieste, Italy, 1999) A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of European and Historical Studies Faculty of Humanities La Trobe University Bundoora, Victoria, 3086 Australia November 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first debt is to the current and past members of the Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Emigrati e loro Famiglie (FILEF, that is the Italian Federation of Migrant Workers and their Families) without whose co-operation and support this research could not have been undertaken. Many have kindly provided various recollections of their own past political activism, as well as epistolary and photographic material—a surviving fragment of what might arguably be called the collective memory of FILEF. The recent passing of Vincenzo Mammoliti, Ignazio Salemi has made their testimonies even more valuable for this study1. Particular thanks are due to Giovanni Sgrò, the veteran secretary of FILEF, and wife Anne for allowing me to consult the 1970s record files at the FILEF office in Coburg, Melbourne. I am also grateful to ex-FILEF members Roberto Malara and Gaetano Greco who first talked to me about the organisation and its history, and put me in contact with many other ‘Filefians’. I would especially like to thank my supervisor Antonio Pagliaro, my postgraduate co- ordinator Dr Nicole Prunster, and the Vaccari Professor of Italian Studies John Gatt-Rutter for their precious support and advice throughout my PhD candidature. A debt of gratitude is also due to fellow student Josara De Lange for her support and counsel in editing and proofreading this thesis. -

Signs of Italian Culture in the Urban Landscape of Carlton

signs of italian culture in the urban landscape of carlton by THIS IS PART TWO OF A RESEARCH Melbourne, was originally inhabited by PROJECT CONDUCTED BY THE AUTHOR the Wurundjeri people, members of the ALICE GIULIA DAL BORGO Woiwurrung language group. European IN MELBOURNE IN 2004 IN ASSOCIATION settlement caused irreversible damage to WITH THE INSTITUTE OF HUMAN the ecosystem on which the Wurundjeri GEOGRAPHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF depended as well as to their social and MILAN AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF cultural systems. The colonists claimed THE ITALIAN AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE Wurundjeri lands for grazing, forcing the (IAI) IN MELBOURNE. THE PROJECT WAS traditional owners into areas populated SUPPORTED BY A SCHOLARSHIP FROM by other clans and into conflict with these THE EUROPEAN UNION’S MARCO POLO communities. Such was the feeling of PROGRAMME. IN CONDUCTING HER hopelessness and displacement between RESEARCH, DAL BORGO DREW HEAVILY the 1840s and 1850s that Wurundjeri ON RECORDS FROM THE ITALIAN parents practiced infanticide. A last vain attempt to regain the land taken by HISTORICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION Europeans was met with gunfire. The AND ON KEY SOURCES INCLUDING indigenous community was further ravaged SAGAZIO’S ‘A WALK THROUGH ITALIAN by infectious diseases, such as smallpox, CARLTON’ (1988) AND ‘YULE’S CARLTON: influenza and venereal diseases introduced A HISTORY’ (2004). by the colonisers. By the end of 1850, the remains of the Wurundjeri community had IN 2001, DAL BORGO OBTAINED A retreated to a small pocket of land to the DEGREE FROM THE FACULTY OF ARTS north of the city. In 1863, by government AND PHILOSOPHY, MILAN UNIVERSITY, edict, this group was relocated to a MAJORING IN ENVIRONMENTAL property near Healesville. -

LIZ TRIPODI 62A Wingara Ave East Keilor

LIZ TRIPODI 62a Wingara Ave East Keilor. Vic.3033 PH: 03 9016 0032 MOBILE: 0438 419553 EMAIL: [email protected] TEACHING EXPERIENCE: ADJUDICATOR/JUDGE SERVICES: Director/Creator of Vocal Art Studios (2003-Current) Team of 18 Teachers and Support Staff Melbourne Singing, Music and Entertainment School with over 200 Private students. Royal South Street Ballarat: Modern Vocal, Country, Personally taught over 500 Private Vocal Students, Beginners to Professionals Vocal Duos/Trios, Vocal Ensembles Skills Taught Include: Geelong Eisteddfod: Modern Vocal, Junior Vocal, Vocal exercises * Breathing *Harmony skills Classical Vocal, Ensembles, Duos Vocal flexibility * Range extension City of Boorandarra Eisteddfod: Contemporary Tone development * Pitch Microphone technique * Song Repertoires * Music theory Vocal, Ensembles, Duos Sight-reading for singers * Timing Performance development * Pronunciation and Speech work Gladstone Park Talent Quest: Vocal Recording techniques Up in Lights: Modern Vocal Audition preparation * Movement for Singers Light and shade * Understanding the music industry Kp Idol: Modern Vocal Exam Preparation for AMEB & ANZCA Exams Competition and Performance Preparation, Workshops, Duos/Trios, Groups, Choirs Brimbank Secondary Idol: Modern Vocal, Ensembles Head of Music: Melbourne School of Performing Arts (2002) Choreographer for Calabria Mia (2001-2003) La Dolce Italia Festival Audition Panel: Modern Vocal Coach for Unicorn Theatre Company (1996) Vocal, Classical Vocal Dance and Singing Teacher for Dancentre -

Aap Submission to the Senate Inquiry on Media Diversity

AAP SUBMISSION TO THE SENATE INQUIRY ON MEDIA DIVERSITY AAP thanks the Senate for the opportunity to make a submission on the Inquiry into Media Diversity in Australia. What is a newswire A newswire is essentially a wholesaler of fact-based news content (text, pictures and video). It reports on politics, business, courts, sport and other news and provides this to other media outlets such as newspapers, radio and TV news. Often the newswire provides the only reporting on a subject and hence its decisions as to what to report play a very important role in informing Australians about matters of public interest. It is essential democratic infrastructure. A newswire often partners with other global newswire agencies to bring international stories to a domestic audience and also to take domestic stories out to a global audience. Newswires provided by news agencies have traditionally served as the backbone of the news supply of their respective countries. Due to their business model they contribute strongly to the diversity of media. In general there is a price for a defined number of circulation – be it printed papers, recipients of TV or radio broadcasters or digital recipients. The bigger the circulation, the higher the price thus making the same newswire accessible for small media with less purchasing power as well as for large media conglomerates with strong financial resources.1 This co-operative business model has been practically accepted world-wide since the founding of the Associated Press (AP) in the USA in the mid-19th century. Newswire agencies are “among the oldest media institutions to survive the evolution of media production from the age of the telegraph to the age of 2 platform technologies”. -

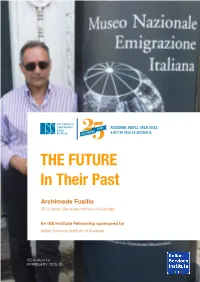

THE FUTURE in Their Past

PASSIONATE PEOPLE. GREAT IDEAS. YEARSYEARS A BETTER SKILLED AUSTRALIA. CELEBRATINGCELEBRATING THE FUTURE In Their Past Archimede Fusillo 2013 Italian Services Institute of Australia An ISS Institute Fellowship sponsored by Italian Services Institute of Australia ISS Institute Inc FEBRUARY 2015 © ISS Institute T 03 9347 4583 Level 1 F 03 9348 1474 189 Faraday Street [email protected] Carlton Vic E AUSTRALIA 3053 W www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne Extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute February 2015 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report or any links therein, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In late August and September of 2014, the Fellow travelled to various regions of Italy, including Basilicata, Lazio, Tuscany and Umbria, to seek out and interview people who had at one stage in their lives migrated to Australia and subsequently returned permanently to Italy - though not necessarily to their place of birth or origin. -

Chronology of Recent Events

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 11 March 2001 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074, 07-3279 2279, [email protected] 11.1 COPY DEADLINE, SUBSCRIPTION NOTICE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for copy for the next Newsletter is 30 April 2001. The Newsletter is online through the “publications” link from the University of Queensland’s Journalism Website at www.uq.edu.au/jrn/ CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS 11.2 NEW PAPERS HIT MELBOURNE TRACKS News Ltd announced its first, but John Fairfax published its first: a commuter newspaper for Melbourne. Fairfax launched their Melbourne Express on the morning of 5 February, and News Ltd their MX on the afternoon of the same day. Both companies distributed about 60,000 copies of the 32-page tabloid papers. News Ltd’s MX, a full-colour production, is aimed at the 18 to 39 year old audience; Fairfax’s Express is aimed at a slightly older audience. News has secured exclusive distribution rights at rail platforms and will eventually provide the papers to commuters in bins; Fairfax said it would continue to employ people to hand out the Express outside train stations and elsewhere. According to MX’s rate card, a full page ad costs $4,500; in the Express it costs $4,256. On 26 January the Age had reported the impending News Ltd commuter paper. John Fairfax Holdings had planned a similar paper called Express in Melbourne and Sydney in May 2000, but abandoned the idea once News threatened to launch a rival publication.