Ballot Design, Voter Intentions, and Representation: a Study of the 2018 Midterm Election in Florida1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(202-224-6020) & United States Mail the Honorable Charles E. Grassley

March 27, 2015 Via Fax (202-224-6020) & United States Mail The Honorable Charles E. Grassley Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate 224 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Via E-mail ([email protected]) and United States Mail The Honorable Patrick J. Leahy Ranking Member, Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate 437 Russell Senate Building Washington, DC 20510 Re: Nomination of Mary Barzee Flores to the United States District Court, Southern District of Florida Dear Chairman Grassley and Ranking Member Leahy: We are former Assistant State Attorneys and we write in support of the confirmation of Mary Barzee Flores to become a United States District Judge for the Southern District of Florida. Although since leaving the Miami-Dade State Attorney's Office our professional paths have taken us in varied directions, we all fondly remember practicing before Judge Barzee. Our experiences before her have convinced us all that she has the intelligence, integrity, demeanor, judgment, and commitment to justice necessary to be an excellent addition to the federal bench. Judge Barzee graduated cum laude from the University of Miami School of Law, and thereafter tried federal cases with the Federal Public Defender's Office in Miami. In 2002, she was elected without opposition to Florida's Eleventh Judicial Circuit Comi in Miami, Florida, re-elected to the court in 2008 and served until 2011. We practiced before Judge Barzee when she was assigned to the criminal division and were sony to see her retire from the state court bench to return to the practice of law. -

CABA Briefs Winter 2013

WINTER | 2013 2013 Board Installation GALA Special Thanks to the 2012 Board. GLOBAL COMPLIANCE 4 www.cabaonline.com WINTER 2013 CONTENTS 06 Meet the Board 07 President’s Message 09 Immediate Past President’s Message 12 A Special Thanks to the 2012 Board and a Big Welcome to the 2013 Board! 16 Editor’s Message 17 Chair’s Message 18 Legal Round Up 24 Judge William Thomas Nomination to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida 26 American Red Cross Piece Continuing a Major Relief Operation to Help Victims of Hurricane Sandy 28 The National Association of Women Judges 34th Annual Conference 32 4,000 Former NFL Players Suing the NFL 36 Do Good for Others and Help Yourself: Take a Pro Bono Case and Improve your Litigation Skills Too 48 About the New State Court Judges 56 CABA’s Pro Bono Project Assists the Victims of Foreclosure Fraud 64 Dichos de Cuba 66 La Cocina de Christina Art in the Tropics 67 Moving Forward ON OCTOBER 13, 2012, CABA PRO BONO 42 PROJECT, INC. HELD ITS ANNUAL “ART IN THE TROPICS” CHARITABLE AUCTION FUNDRAISING WINTER | 2013 ON THE EVENT AT TROPICAL FAIRCHILD GARDENS. COVER 2013 Board Installation CABA’S INSTALLATION GALA GALA 12 Special Thanks The Cuban American Bar to the 2012 Board. Association special thanks to the 2012 Board and big welcome to the 2013 Board of Directors and Sandra M. Ferrera as President. CABA BRIEFS | WINTER 2013 5 MEET THE BOARD President Sandra M. Ferrera Partner, Meland Russin & Budwick, P.A. President-Elect Vice President Ricardo M. -

ABATE of FLORIDA, INC. SOUTHEAST CHAPTER a Newsletter for Motorcycle Safety & Awareness ISSUE 409 AUGUST 2017

ABATE OF FLORIDA, INC. SOUTHEAST CHAPTER a Newsletter for Motorcycle Safety & Awareness ISSUE 409 AUGUST 2017 A MERICAN B IKERS A IMING T OWARD E DUCATION NEXT CHAPTER MEETING 10 AM August 20, 2017 at American Legion Post 222 LET THOSE WHO RIDE DECIDE! Happy 4th of July ABATE OF FLORIDA, INC. FALL STATE BIKER BASH November 3rd - 5th, 2017 GATES OPEN: Friday at Noon, GATES CLOSE: Sunday at Noon PEACE RIVER CAMPGROUNDS 2998 Northwest Highway 70, Arcadia Florida 34266 LIVE MUSIC BOTH DAYS SCHEDULED RIDE SATURDAY BIKE GAMES VENDORS CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES WEEKEND ADMISSION: 2 DAYS (Friday check-in) - $30 in Advance, $35 at Gate. 1 DAY (Saturday check-in) $20 at Gate. Includes primitive tent camping on a first ² come, first serve basis. Any RV/Trailer Camping must contact Campground. CONTACT CAMPGROUND AT: 863.494.9693 for RV/Trailer Camping. Mention ABATE for discounted pricing. NO CHILDREN OR PETS IN EVENT AREA: Childrens activites provided by CMA outside of Event area. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON FALL STATE BIKER BASH EVENT CALL: BILLY BIRD 941.249.1276 (or talk to your local ABATE Chapter) VENDOR INFORMATION CONTACT: Michelle Adams 941.875.3293 CAMPING ARRANGEMENTS CONTACT: Peace River Campground 863.494.9693 www.abateflorida.com SAFETY AND MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION AVAILABLE. ABATE OF FLORIDA, INC. DOES NOT CONDONE DRINKING AND RIDING. DONATIONS TO ABATE OF FLORIDA, INC. ARE NOT DEDUCTIBLE FOR FEDERAL INCOME TAX PURPOSES. A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE WITHIN THE STATE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE. -

February NEWSLETTER

February DWC NEWSLETTER DEMOCRATIC WOMEN’S CLUB OF MANATEE COUNTY FLORIDA WWW.DWCManatee.com Kathie Marsh is a Museum Specialist for the Family Heritage House Museum on SCF campus on 26th St W, Bradenton, Florida. She manages the operations of an African American Gallery and Resource Center, a non-profit faculty with a mission to inspire children to have respect for their ancestors, a love for learn- ing, and a passion for service; to strengthen black families and empower them to maintain historical bonds of kinship; and to assist in the promulgation of the culture for the benefit of the general population. Kathie is a graduate Cum Laude from Manatee Com- munity College, now the State College of Florida and includes in her resume’ a degree in Business Admin- istration for the University of South Florida a degree Guest Speaker in Business administration. Kathie Marsh She has received many awards through her career and is very active in the local community including DWC LUNCHEON service with the United Way, Meals on Wheel, Just for Girls and the Bradenton Housing Authority. February 13th 2018, 11:30 AM Charles Smith who is running for County Commis- 4350 El Conquistador Pkwy sioner will also be attending our meeting to discuss his campaign. Bradenton, FL Please make your reservations by Noon February 9th, 2018 It’s Time to Renew Your Call Sandy Gander 941.758.7187 Membership! Dues for 2018 are now due. If you haven’t yet re- or email newed, it’s easy. Just mail a $25 check made out to DWC to: [email protected] Joanie LeBaron, Treasurer Menu: Buffet includes salad, grilled 834 Wee Burn Street chicken, cold cuts, cheeses, bread and cookie Sarasota, FL 34243 Questions? Call or email Joanie. -

2018NOV26 Ftm9:25 Miamidade.Gov If F " Ur Tfic CITY CLERK CITY 6F MIAMI

Elections 2700 NW 87th Avenue MIAMI-DADE Miami, Florida 33172 COUNTY T 305-499-VOTE F 305-499-8547 TTY: 305-499-8480 2018NOV26 ftM9:25 miamidade.gov if f " Ur Tfic CITY CLERK CITY 6F MIAMI CERTIFICATION STATE OF FLORIDA) COUNTY OF MIAMI-DADE) I, Christina White, Supervisor of Elections for Miami-Dade County, Florida, do hereby certify that the attached is a true and correct copy of the Official Results for the Miami-Dade County General Election conducted on November 6, 2018, which included the Miami Special Election. WITNESS MY HAND AND OFFICIAL SEAL, AT MIAMI, MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA, IRI^TIKIA WHITE '" ■ ' ' f * " Supervisor of Elections ON,THIS 17^^ DAY OF NOVEMBER, 2018 Miami-Dade County ■ I ■ ! 's. ' ') . Enclosure SUMMARY REPT-GROUP DETAIL OFFICIAL GENERAL ELECTION OFFICIAL RESULTS NOVEMBER 6. 2018 MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FL RUN DATE:11/19/18 11:55 AH REPORT-ELABA PAGE 001 TOTAL VOTES ED OSS ED IVO VBM EV OSS EV IVO PROV PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 907). 907 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 1428.843 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 813.353 241,072 28 269,993 302,013 41 206 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 56,92 UNITED STATES SENATOR *** See Addendum *** Vote for 1 R1ck Scott (REP) CO Bill Nelson (DEM) WRITE-IN. CJ'" CO Total . ^££ ADDENDUM -c r 1 Over Votes . rs5 r:) Under Votes . cnrl X. en nj REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS, DIST. 23 ZX rn Vote for 1 CJ Joseph "Joe" Kaufman (REP). 10,160 42.54 3,434 0 3,258 3,464 2 2 ~c-> 0 2 Debbie Wasserman Schultz (DEM) . -

ARIZONA, FLORIDA, and OKLAHOMA RUNOFF

PRIME-ARY PERSPECTIVE: ARIZONA, FLORIDA, and OKLAHOMA RUNOFF PRIME-ARY Perspectives is a series that will give you an overview of the most noteworthy results from each state's primary election, focusing on congressional districts that are likely to be most competitive in November, as well as those that will have new representation in 2019 because of retirements. As always, please do not hesitate to reach out to us with questions! ARIZONA Arizona will feature a number of highly competitive races in November, from statewide gubernatorial and Senate races to several House races. While Arizona was been reliably Republican in recent years, demographic changes combined with President Trump's unpopularity give Democrats an opportunity to make up ground here. GUBERNATORIAL Incumbent Governor Doug Ducey fended off a primary opponent from Arizona's Secretary of State, Ken Bennett, receiving 70% of the vote. Ducey's bid for a second term will be one of the most well-funded campaigns in the country, already having amassed along with the Republican Governors Association over $9 million of airtime. The race is rated as "Likely Republican." David Garcia (D) David Garcia won yesterday's three-way Democratic primary for governor with 48% of the vote. Garcia is a Mesa native and U.S. Army veteran who most recently ran for Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction and lost in 2014. Garcia intends on capitalizing on the broken state of public education in Arizona, where statewide teacher strikes took place in April. If Garcia succeeds in November, he would make the state's first Latino governor since Raul Castro in 1975. -

US Election Insight 2018

dentons.com US Election Insight 2018 Election results data contained in this report reflect data as of November 20th at 9:00pm Eastern Standard Time (EST). US ELECTION INSIGHT 2018 // DENTONS.COM A Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................... 1 THE RESULTS Senate ...................................... 5 House ....................................... 7 Governors .................................... 10 State Legislatures ................................ 11 State Attorneys General ............................ 13 Score Cards ................................... 14 Ballot Initiatives ................................. 30 Recount Rules by State ............................ 31 What We Don’t Know .............................. 32 NUMBERS BEHIND THE RESULTS A Look at the “Pivot” Districts ......................... 32 Open Seats ................................... 34 Polls vs. Results ................................. 36 CANDIDATES BEHIND THE RESULTS Faces of the Newly Elected .......................... 37 Firsts ....................................... 46 116th Congress-Freshman Women ...................... 46 Demographics .................................. 47 Size of Freshman Class ............................ 47 116TH CONGRESS Potential Senate Leadership ......................... 48 Current House Leadership .......................... 50 Potential Party Leadership Positions and Party Caucus Leaders .... 51 Potential House Committee Chairs ..................... 52 Issue Matrix for the 116th Congress ..................... 53 Policy -

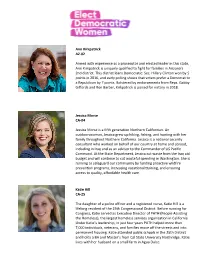

Ann Kirkpatrick AZ-02 Armed with Experience As a Prosecutor And

Ann Kirkpatrick AZ-02 Armed with experience as a prosecutor and elected leader in this state, Ann Kirkpatrick is uniquely qualified to fight for families in Arizona’s 2nd district. This district leans Democratic: Sec. Hillary Clinton won by 5 points in 2016, and early polling shows that voters prefer a Democrat to a Republican by 7 points. Bolstered by endorsements from Reps. Gabby Giffords and Ron Barber, Kirkpatrick is poised for victory in 2018. Jessica Morse CA-04 Jessica Morse is a fifth generation Northern Californian. An outdoorswoman, Jessica grew up hiking, fishing, and hunting with her family throughout Northern California. Jessica is a national security consultant who worked on behalf of our country at home and abroad, including in Iraq and as an advisor to the Commander of US Pacific Command. At the State Department, Jessica cut waste from the Iraq aid budget and will continue to cut wasteful spending in Washington. She is running to safeguard our community by funding proactive wildfire prevention programs, increasing vocational training, and ensuring access to quality, affordable health care. Katie Hill CA-25 The daughter of a police officer and a registered nurse, Katie Hill is a lifelong resident of the 25th Congressional District. Before running for Congress, Katie served as Executive Director of PATH (People Assisting the Homeless), the largest homeless services organization in California. Under Katie’s leadership, in just four years PATH helped more than 7,000 individuals, veterans, and families move off the streets and into permanent housing. Katie attended public schools in the 25th District and holds a BA and Master’s from Cal State University Northridge. -

19, 2012 “Women in the Courtroom” Trial Skills for Women Lawyers

The Florida Association for Women Lawyers and its Miami-Dade Chapter, with Judge Gill S. Freeman, 11th Judicial Circuit, Miami-Dade, Florida, and with assistance from the Litigation Skills Program, University of Miami School of Law, are pleased to present: “Women in the Courtroom” Trial Skills for Women Lawyers October 17 - 19, 2012 Investors’ Rights Law Firm ● Supporting Women Lawyers www.vernonhealy.com 999 Vanderbilt Beach Road Suite 200, Naples, FL 34108 239-649-5390 The hiring of a lawyer is an important decision that should not be based solely upon advertisement. Before you decide, ask us to send you free written information about our qualifications and experience. 2525 Ponce de Leon Blvd., Suite 700 Coral Gables, FL 33134 Phone: (305) 854-0800 wsh-law.com Wednesday, October 17, 2012 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. Kick-Off Panel Reception “Overcoming Gender Bias: Getting into the Courtroom and Succeeding There” Hosted by Shook, Hardy & Bacon LLP Julie Braman Kane, Esq., Colson Hicks Eidson Detra Shaw-Wilder, Kozyak, Tropin & Throckmorton Hassia Diolombi, Esq., Shook, Hardy & Bacon Moderator: Corali Lopez-Castro, Kozyak, Tropin & Throckmorton Julie Braman Kane, a partner of Colson Hicks Edison, has over fifteen years’ experience in personal injury, medical malpractice, products liability, commercial and class action litigation, and has handled multiple multi-million dollar verdicts and settlements involving significant injury. She has served as President of the Miami- Dade Chapter of FAWL. She is actively involved in the American Association for Justice (AAJ), where she serves on the Board of Governors, the Justice PAC Board of Trustees, and the National Board of Advocates Board of Trustees. -

Florida Advisory Committee

Florida Advisory Committee These business, faith, military, and community leaders believe that Florida benefits when America leads in the world through investments in development and diplomacy. Hon. Ander Crenshaw Hon. Alex Sink Co-Chairs U.S. House of Representatives CFO of the State of Florida (2001-2017) (2007-2011) Hon. Michael I. Abrams Dr. Teo A. Babun, Jr. Hon. Aaron Bowman* Ballard Partners Outreach Aid to the Americas JAXUSA Partnership Partner & Miami Office Co-Chair Chairman Senior Vice President of Business Florida House of Representatives BG Consultants Development Member (1982-1994) CEO Jacksonville City Council Member Brig. Gen. John Adams* Lauren Baer U.S. Army Albright Stonebridge Group Phillip Brown Retired U.S. Department of State Greater Orlando Aviation Authority Secretary of State’s Policy Planning Staff Chief Executive Officer Hon. Sandy Adams* (2011-2016) U.S. House of Representatives Hon. Doug Broxson Senior Advisor to the U.S. Ambassador to Member (2011-2013) Florida State Senate the U.N. (2016-2017) Member Manuel Almira Jonathan Baety Port of Palm Beach Bob Burleson Conrad Santiago & Associates Executive Director Partner, Tallahassee Office Financial Advisor Ballard Partners Hon. Liz Alpert Ryan Barras City of Sarasota Jeb Bush, Jr. Tekesta Consulting Mayor Jeb Bush & Associates, LLC Founder & Owner CEO Hon. Jason Altmire Oliver Barrett* Bush Realty, LLC U.S. House of Representatives Center for Climate and Security President Member (2007-2013) Senior Research Fellow Régine B. Cambronne Annette Alvarez Hon. Dick J. Batchelor* Baptist Health Foundation Global Ties Miami Dick Batchelor Management Group, Inc. Director of Development Executive Director President Jim Cameron Walter Alvarez Hon.