Quitting Shadow Cabinet (1987)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impartiality in Opinion Content (July 2008)

Quality Assurance Project 5: Impartiality (Opinion Content) Final Report July 2008 Advise. Verify. Review ABC Editorial Policies Editorial Policies The Editorial Policies of the ABC are its leading standards and a day-to-day reference for makers of ABC content. The Editorial Policies – • give practical shape to statutory obligations in the ABC Act; • set out the ABC’s self-regulatory standards and how to enforce them; and • describe and explain to staff and the community the editorial and ethical principles fundamental to the ABC. The role of Director Editorial Policies was established in 2007 and comprises three main functions: to advise, verify and review. The verification function principally involves the design and implementation of quality assurance projects to allow the ABC to assess whether it is meeting the standards required of it and to contribute to continuous improvement of the national public broadcaster and its content. Acknowledgements The project gained from the sustained efforts of several people, and the Director Editorial Policies acknowledges: Denis Muller, Michelle Fisher, Manager Research, and Jessica List, Executive Assistant. Thanks also to Ian Carroll and John Cameron, respectively the Directors of the Innovation Division and the News Division, and to their senior staff, whose engagement over the details of editorial decision-making gave the project layers that an assessment of this sort usually lacks. This paper is published by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation © 2008 ABC For information about the paper, please contact: Director Editorial Policies ABC Southbank Centre GPO Box 9994 Melbourne VIC 3001 Phone: +61 3 9626 1631 Email: [email protected] QA Project 05 – Final Report July 2008 ABC Editorial Policies Foreword Opinion and impartiality – are there any other words which, when paired, are more fraught for a public broadcaster? Is any other pair of words more apparently paradoxical? Opinion content is commissioned or acquired by the ABC to provide a particular perspective or point of view. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

Fraser Minister Critical of Turnbull's Rejection Of

Fraser minister critical of Turnbull’s rejection of indigenous voice Former Aboriginal affairs minister Fred Chaney. • The Australian • 17January 2018 • Rick Morton Malcolm Turnbull and his government, in their swift rejection of a proposed indigenous voice to parliament, have either “misunderstood or misrepresented” the idea in a way that tried to “turn the clock backward,” the former Aboriginal affairs minister Fred Chaney said. Mr Chaney, a minister in the Fraser government and a deputy leader of the Liberal Party, said there was “confusion” in the government’s response to the Referendum Council’s recommendations on constitutional recognition. “I found the government’s response very troubling because it talked about equal citizenship, an idea this nation has already addressed with a previous referendum and full legal citizenship,” he said. Speaking particularly about an indigenous body that would act as a “voice” to parliament — something some Coalition MPs dismissed as a “third chamber of parliament” — Mr Chaney said it was a “generous” concession to constitutional conservatives. “Through this whole process, Aboriginal people have removed the logs in the path, this idea that there would be a bill of rights, that it would disturb the balance between the parliament and the courts, all of these things have been removed,” he said. 2 “All we are asking is for the specific existence and survival of Aboriginal people to be acknowledged. We essentially tried to annihilate them, to wipe their culture and language from the country, and they survived. It is a heroic story. This is a very gentle proposal … which would allow Aboriginal people to be heard on legislation that affects them.” • READ MORE • They were first — we should listen University of NSW professor of law and constitutional lawyer Megan Davis, who is also a Referendum Council member, said there had been a “fundamental misunderstanding” of the issue in government. -

In This Edition

NATIONAL COUNCIL of WOMEN WA Inc PATRON: Hon Kerry Sanderson AO VICE PATRON: Janet Davidson AOM JP PRESIDENT: Marion Ward SECRETARY: Helen McDonagh Act TREASURER: Sally Warner Rod Evans Community Centre 160 Hay St East Perth WA 6004 GPO Box 6224 East Perth 6892 Phone: 9325 8897 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncwwa.org.au President’s Message November 2014 Dear Members The COTA AGM was held at the State Library e and Mr. Fred Chaney gave the most interesting m ur year is drawing to a close and this will a address “Reinventing Aging”. Mr. Chaney felt i be our last newsletter for 2014. During that aging is a time of loss – loss of friends, ability l January you will receive an update on the : O to do all the things we have enjoyed in the past, arrangements for International Women’s Day so sometimes loss of memory. As usual his talk was n that we will have numbers in early for catering c thought provoking but with a great deal of humor. w purposes. You have already received your 2015 Marie Moloney was returned to the Board for a w calendar so you will be able to plan your year. further term of three years. Congratulation Marie! a @ Another of our wonderful women, volunteering i The highlight of this month has been the ANZAC i Commemoration for the departure of the many hours to assist in delivering service to n Expeditionary Forces from Albany one hundred others. e t years ago. Hopefully many of you were able to . -

The Most Vitriolic Parliament

THE MOST VITRIOLIC PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE OF THE VITRIOLIC NATURE OF THE 43 RD PARLIAMENT AND POTENTIAL CAUSES Nicolas Adams, 321 382 For Master of Arts (Research), June 2016 The University of Melbourne, School of Social and Political Sciences Supervisors: Prof. John Murphy, Dr. Scott Brenton i Abstract It has been suggested that the period of the Gillard government was the most vitriolic in recent political history. This impression has been formed by many commentators and actors, however very little quantitative data exists which either confirms or disproves this theory. Utilising an analysis of standing orders within the House of Representatives it was found that a relatively fair case can be made that the 43rd parliament was more vitriolic than any in the preceding two decades. This period in the data, however, was trumped by the first year of the Abbott government. Along with this conclusion the data showed that the cause of the vitriol during this period could not be narrowed to one specific driver. It can be seen that issues such as the minority government, style of opposition, gender and even to a certain extent the speakership would have all contributed to any mutation of the tone of debate. ii Declaration I declare that this thesis contains only my original work towards my Masters of Arts (Research) except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text to other material used. Equally this thesis is fewer than the maximum word limit as approved by the Research Higher Degrees Committee. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my two supervisors, Prof. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

Preparation for Government by the Coalition in Opposition 1983–1993 1 Contents

SUMMER SCHOLAR’S PAPER December 2014 ‘In the wilderness’: preparation for government by the Coalition 1 in opposition 1983–1993 Marija Taflaga Parliamentary Library Summer Scholar 2014 Executive summary • This paper examines the Coalition’s policy and preparation efforts to transition into government between 1983 and 1993. • The role of the opposition in the Australian political system is examined and briefly compared with other Westminster countries. The paper also outlines the workings of the shadow Cabinet and the nature of the working relationship between the Liberal Party (LP) and The Nationals (NATS) as a Coalition. • Next, the paper provides a brief historical background of the Coalition’s history in power from 1949 to 1983, and the broader political context in Australia during those years. • Through an examination of key policy documents between 1983 and 1993, the paper argues that different approaches to planning emerged over the decade. First a diagnostic phase from 1983–1984 under the leadership of Andrew Peacock. Second, a policy development phase from 1985–1990 under the leadership of both Peacock and John Howard. The third period from 1990 ̶ 1993 under Dr John Hewson was unique. Hewson’s Opposition engaged in a rigorous and sophisticated regime of policy making and planning never attempted before or since by an Australian opposition. The LP’s attempts to plan for government resulted in the institutionalisation of opposition policy making within the LP and the Coalition. • Each leader’s personal leadership style played an important role in determining the processes underpinning the Coalition’s planning efforts in addition to the overall philosophical approach of the Liberal-led Coalition. -

Report No 3 the Use of “Henry VIII Clauses” in Queensland Legislation

The use of “Henry VIII Clauses” in Queensland Legislation Laid on the table and ordered to be printed. Scrutiny of Legislation Committee. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND THE SCRUTINY OF LEGISLATION COMMITTEE THE USE OF “HENRY VIII CLAUSES” IN QUEENSLAND LEGISLATION JANUARY 1997 Scrutiny of Legislation Committee – Membership – 48th Parliament 2nd Session Chairman: Mr Tony Elliott MLA, Member for Cunningham Deputy Chairman: Mr Jon Sullivan MLA, Member for Caboolture Other Members: Mrs Liz Cunningham MLA, Member for Gladstone Hon Dean Wells MLA, Member for Murrumba1 Mr Neil Roberts MLA, Member for Nudgee Mr Frank Tanti MLA, Member for Mundingburra Legal Adviser To The Committee: Professor Charles Sampford Committee Staff: Ms Louisa Pink, Research Director Mr Simon Yick, Senior Research Officer Ms Cassandra Adams, Executive Assistant Ms Bronwyn Rout, Casual Administration Officer Scrutiny of Legislation Committee Level 6, Parliamentary Annexe George Street Brisbane QLD 4000 Phone: 07 3406 7671 Fax: 07 3406 7500 Email: [email protected] 1 Mr Paul Lucas MLA, Member for Lytton, replaced the Hon Dean Wells MLA, as a Member of the committee on 4 December 1996 Chairman’s Foreword Chairman’s Foreword For the past twenty-one years this Committee and its predecessor, the Subordinate Legislation Committee, have been making adverse reports to Parliament on provisions in legislation regarded as “Henry VIII clauses”. A “Henry VIII clause” is one which permits an Act of Parliament to be amended by subordinate legislation. However, no Parliamentary Committee in Queensland has, to date, conducted a detailed analysis of the use of such clauses. The Subordinate Legislation Committee resolved in 1995 to undertake such an examination. -

Engaging the Neighbours AUSTRALIA and ASEAN SINCE 1974

Engaging the neighbours AUSTRALIA AND ASEAN SINCE 1974 Engaging the neighbours AUSTRALIA AND ASEAN SINCE 1974 FRANK FROST Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Frost, Frank, 1947- author. Title: Engaging the neighbours : Australia and ASEAN since 1974 / Frank Frost. ISBN: 9781760460174 (paperback) 9781760460181 (ebook) Subjects: ASEAN. Australia--Foreign relations--Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia--Foreign relations--Australia. Dewey Number: 327.94059 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents Chronology . vii Preface . xi Abbreviations . xiii Introduction . 1 1 . Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) . 7 2 . Economic disputes and the Third Indochina War (1976–1983) . 35 3 . Regional activism and the end of the Cold War (1983–1996) . 65 4 . The Asian financial crisis, multilateral relations and the East Asia Summit (1996–2007) . 107 5 . From the ‘Asia Pacific Community’ to the fortieth anniversary summit and beyond (2007‒2015) . .. 145 6 . Australia and ASEAN: Issues, themes and future prospects . 187 Bibliography . 205 Index . 241 Chronology 1945 Declaration of -

Votes and Proceedings

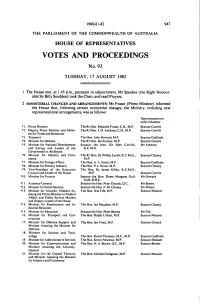

1980-81-82 947 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 93 TUESDAY, 17 AUGUST 1982 1 The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honour- able Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) informed the House that, following certain ministerial changes, the Ministry, including new representational arrangements, was as follows: Representationin other Chamber *1. Prime Minister The Rt Hon. Malcolm Fraser, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick *2. Deputy Prime Minister and Minis- The Rt Hon. J. D. Anthony, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick ter for Trade and Resources *3. Treasurer The Hon. John Howard, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *4. Minister for Defence The Rt Hon. lan Sinclair, M.P. Senator Durack *5. Minister for National Development Senator the Hon. Sir John Carrick, Mr Anthony and Energy and Leader of the K.C.M.G. Government in the Senate *6. Minister for Industry and Com- The Rt Hon. Sir Phillip Lynch, K.C.M.G., Senator Chaney merce M.P. *7. Minister for Foreign Affairs The Hon. A. A. Street, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *8. Minister for Primary Industry The Hon. P. J. Nixon, M.P. Senator Chancy *9. Vice-President of the Executive The Hon. Sir James Killen, K.C.M.G., Council and Leader of the House M.P. Senator Carrick *10. Minister for Finance Senator the Hon. Dame Margaret Guil- Mr Howard foyle, D.B.E. *11. Attorney-General Senator the Hon.