What Evolutionary Processes Do the Mollusca Show?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

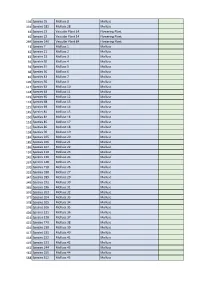

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Revision of the Systematic Position of Lindbergia Garganoensis

Revision of the systematic position of Lindbergia garganoensis Gittenberger & Eikenboom, 2006, with reassignment to Vitrea Fitzinger, 1833 (Gastropoda, Eupulmonata, Pristilomatidae) Gianbattista Nardi Via Boschette 8A, 25064 Gussago (Brescia), Italy; [email protected] [corresponding author] Antonio Braccia Via Ischia 19, 25100 Brescia, Italy; [email protected] Simone Cianfanelli Museum System of University of Florence, Zoological Section “La Specola”, Via Romana 17, 50125 Firenze, Italy; [email protected] & Marco Bodon c/o Museum System of University of Florence, Zoological Section “La Specola”, Via Romana 17, 50125 Firenze, Italy; [email protected] Nardi, G., Braccia, A., Cianfanelli, S. & Bo- INTRODUCTION don, M., 2019. Revision of the systematic position of Lindbergia garganoensis Gittenberger & Eiken- Lindbergia garganoensis Gittenberger & Eikenboom, 2006 boom, 2006, with reassignment to Vitrea Fitzinger, is the first species of the genus, Lindbergia Riedel, 1959 to 1833 (Gastropoda, Eupulmonata, Pristilomatidae). be discovered in Italy. The genus Lindbergia encompasses – Basteria 83 (1-3): 19-28. Leiden. Published 6 April 2019 about ten different species, endemic to the Greek mainland, Crete, the Cycladic islands, Dodecanese islands, northern Aegean islands, and southern Turkey (Riedel, 1992, 1995, 2000; Welter-Schultes, 2012; Bank & Neubert, 2017). Due to Lindbergia garganoensis Gittenberger & Eikenboom, 2006, lack of anatomical data, some of these species remain ge- a taxon with mainly a south-Balkan distribution, is the only nerically questionable. Up to now, L. garganoensis was only Italian species assigned to the genus Lindbergia Riedel, 1959. known by the presence of very fine spiral striae on the tel- The assignment to this genus, as documented by the pecu- eoconch and by the general shape of its shell. -

Fauna of New Zealand Ko Te Aitanga Pepeke O Aotearoa

aua o ew eaa Ko te Aiaga eeke o Aoeaoa IEEAE SYSEMAICS AISOY GOU EESEAIES O ACAE ESEAC ema acae eseac ico Agicuue & Sciece Cee P O o 9 ico ew eaa K Cosy a M-C aiièe acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa EESEAIE O UIESIIES M Emeso eame o Eomoogy & Aima Ecoogy PO o ico Uiesiy ew eaa EESEAIE O MUSEUMS M ama aua Eiome eame Museum o ew eaa e aa ogaewa O o 7 Weigo ew eaa EESEAIE O OESEAS ISIUIOS awece CSIO iisio o Eomoogy GO o 17 Caea Ciy AC 1 Ausaia SEIES EIO AUA O EW EAA M C ua (ecease ue 199 acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 38 Naturalised terrestrial Stylommatophora (Mousca Gasooa Gay M ake acae eseac iae ag 317 amio ew eaa 4 Maaaki Whenua Ρ Ε S S ico Caeuy ew eaa 1999 Coyig © acae eseac ew eaa 1999 o a o is wok coee y coyig may e eouce o coie i ay om o y ay meas (gaic eecoic o mecaica icuig oocoyig ecoig aig iomaio eiea sysems o oewise wiou e wie emissio o e uise Caaoguig i uicaio AKE G Μ (Gay Micae 195— auase eesia Syommaooa (Mousca Gasooa / G Μ ake — ico Caeuy Maaaki Weua ess 1999 (aua o ew eaa ISS 111-533 ; o 3 IS -7-93-5 I ie 11 Seies UC 593(931 eae o uIicaio y e seies eio (a comee y eo Cosy usig comue-ase e ocessig ayou scaig a iig a acae eseac M Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Māoi summay e y aco uaau Cosuas Weigo uise y Maaaki Weua ess acae eseac O o ico Caeuy Wesie //wwwmwessco/ ie y G i Weigo o coe eoceas eicuaum (ue a eigo oaa (owe (IIusao G M ake oucio o e coou Iaes was ue y e ew eaIa oey oa ue oeies eseac -

Gastropoda Pulmonata: Buliminidae)

BASTERIA, 60: 9-11, 1996 The westernmost Turanena species: T. katerinae spec. nov. (Gastropoda Pulmonata: Buliminidae) E. Gittenberger Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P.O. Box 9517, NL 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands is it Turanena katerinae from western Crete described as new to science. Actually is the westernmost Turanena species known. Key words: Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Buliminidae, Turanena, taxonomy, Greece. In and the recent years our systematic biogeographical knowledge concerning genus Turanena increased considerably (see: Bank & Menkhorst, 1992; Gittenberger & it is Turanena from Menkhorst, 1993). Therefore, relatively easy to recognize a species to the island of Crete as both new science and biogeographically interesting because of its occurrence far to the west in the South Aegean island arc. The collection of the Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum (Leiden) is referred to as NNM. Turanena katerinae spec. nov. (fig- 4) Material.— Greece,Crete, Khania: 0.1-0.2 km NE. ofthe mountain cabin "Katifigio Kalergi" (= 4 km E. of 1600 altitude 56806/ Omalos) [UTM GE6715], below limestone cliffs, among a bushy vegetation, at m (NNM holotype [leg. 5.v. 1993], 56808/1 paratype [leg. 29.iii. 1989], and 56807/7 paratypes peg. 5.v.1993]); 6 km S. of Omalos, Gingolos Mtn. [UTM GE6509] (Colin. W.J.M. Maassen/1 paratype). Shell to about mm and 4 mm broad; its Diagnosis.-- corneous, up 7 high aperture without a reflected and/or prominently thickened lip. Description.— Shell conical, with 4 1/2 to 4 3/4 globular whorls. Umbilicus narrow. Teleoconch whorls with narrowly spaced, irregular riblets. Body whorl not ascending in front. Aperture measuring slightly over 40% of the total shell height. -

Version of the Manuscript

Accepted Manuscript Antarctic and sub-Antarctic Nacella limpets reveal novel evolutionary charac- teristics of mitochondrial genomes in Patellogastropoda Juan D. Gaitán-Espitia, Claudio A. González-Wevar, Elie Poulin, Leyla Cardenas PII: S1055-7903(17)30583-3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.10.036 Reference: YMPEV 6324 To appear in: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Received Date: 15 August 2017 Revised Date: 23 July 2018 Accepted Date: 30 October 2018 Please cite this article as: Gaitán-Espitia, J.D., González-Wevar, C.A., Poulin, E., Cardenas, L., Antarctic and sub- Antarctic Nacella limpets reveal novel evolutionary characteristics of mitochondrial genomes in Patellogastropoda, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (2018), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.10.036 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Version: 23-07-2018 SHORT COMMUNICATION Running head: mitogenomes Nacella limpets Antarctic and sub-Antarctic Nacella limpets reveal novel evolutionary characteristics of mitochondrial genomes in Patellogastropoda Juan D. Gaitán-Espitia1,2,3*; Claudio A. González-Wevar4,5; Elie Poulin5 & Leyla Cardenas3 1 The Swire Institute of Marine Science and School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China 2 CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, GPO Box 1538, Hobart 7001, TAS, Australia. -

Mollusca, Archaeogastropoda) from the Northeastern Pacific

Zoologica Scripta, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 35-49, 1996 Pergamon Elsevier Science Ltd © 1996 The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved 0300-3256(95)00015-1 0300-3256/96 $ 15.00 + 0.00 Anatomy and systematics of bathyphytophilid limpets (Mollusca, Archaeogastropoda) from the northeastern Pacific GERHARD HASZPRUNAR and JAMES H. McLEAN Accepted 28 September 1995 Haszprunar, G. & McLean, J. H. 1995. Anatomy and systematics of bathyphytophilid limpets (Mollusca, Archaeogastropoda) from the northeastern Pacific.—Zool. Scr. 25: 35^9. Bathyphytophilus diegensis sp. n. is described on basis of shell and radula characters. The radula of another species of Bathyphytophilus is illustrated, but the species is not described since the shell is unknown. Both species feed on detached blades of the surfgrass Phyllospadix carried by turbidity currents into continental slope depths in the San Diego Trough. The anatomy of B. diegensis was investigated by means of semithin serial sectioning and graphic reconstruction. The shell is limpet like; the protoconch resembles that of pseudococculinids and other lepetelloids. The radula is a distinctive, highly modified rhipidoglossate type with close similarities to the lepetellid radula. The anatomy falls well into the lepetelloid bauplan and is in general similar to that of Pseudococculini- dae and Pyropeltidae. Apomorphic features are the presence of gill-leaflets at both sides of the pallial roof (shared with certain pseudococculinids), the lack of jaws, and in particular many enigmatic pouches (bacterial chambers?) which open into the posterior oesophagus. Autapomor- phic characters of shell, radula and anatomy confirm the placement of Bathyphytophilus (with Aenigmabonus) in a distinct family, Bathyphytophilidae Moskalev, 1978. -

Bichain Et Al.Indd

naturae 2019 ● 11 Liste de référence fonctionnelle et annotée des Mollusques continentaux (Mollusca : Gastropoda & Bivalvia) du Grand-Est (France) Jean-Michel BICHAIN, Xavier CUCHERAT, Hervé BRULÉ, Thibaut DURR, Jean GUHRING, Gérard HOMMAY, Julien RYELANDT & Kevin UMBRECHT art. 2019 (11) — Publié le 19 décembre 2019 www.revue-naturae.fr DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : Bruno David, Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Jean-Philippe Siblet ASSISTANTE DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITOR : Sarah Figuet ([email protected]) MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Sarah Figuet COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : Luc Abbadie (UPMC, Paris) Luc Barbier (Parc naturel régional des caps et marais d’Opale, Colembert) Aurélien Besnard (CEFE, Montpellier) Vincent Boullet (Expert indépendant fl ore/végétation, Frugières-le-Pin) Hervé Brustel (École d’ingénieurs de Purpan, Toulouse) Patrick De Wever (MNHN, Paris) Thierry Dutoit (UMR CNRS IMBE, Avignon) Éric Feunteun (MNHN, Dinard) Romain Garrouste (MNHN, Paris) Grégoire Gautier (DRAAF Occitanie, Toulouse) Olivier Gilg (Réserves naturelles de France, Dijon) Frédéric Gosselin (Irstea, Nogent-sur-Vernisson) Patrick Haff ner (UMS PatriNat, Paris) Frédéric Hendoux (MNHN, Paris) Xavier Houard (OPIE, Guyancourt) Isabelle Leviol (MNHN, Concarneau) Francis Meunier (Conservatoire d’espaces naturels – Picardie, Amiens) Serge Muller (MNHN, Paris) Francis Olivereau (DREAL Centre, Orléans) Laurent Poncet (UMS PatriNat, Paris) Nicolas Poulet (AFB, Vincennes) Jean-Philippe Siblet (UMS -

Land Snails of Leicestershire and Rutland

Land Snails of Leicestershire and Rutland Introduction There are 50 known species of land snail found in Leicestershire and Rutland (VC55) which represents about half of the 100 UK species. However molluscs are an under-recorded taxon group so it is possible that more species could be found and equally possible that a few may now be extinct in our two counties. There was a 20 year period of enthusiastic mollusc recording between 1967 and 1986, principally by museum staff, which account for the majority of species. Whilst records have increased again in the last three years thanks to NatureSpot, some species have not been recorded for over 30 years. All our land snails are in the class Gastropoda and the order Pulmonata. Whilst some of these species require damp habitats and are generally found near to aquatic habitats, they are all able to survive out of water. A number of species are largely restricted to calcareous habitats so are only found at a few sites. The sizes stated refer to the largest dimension of the shell typically found in adult specimens. There is much variation in many species and juveniles will of course be smaller. Note that the images are all greater than life size and not all the to the same scale. I have tried to display them at a sufficiently large scale so that the key features are visible. Always refer to the sizes given in the text. Status refers to abundance in Leicestershire and Rutland (VC55). However molluscs are generally under- recorded so our understanding of their distribution could easily change. -

Primer Registro Del Gastrópodo Neritáceo Sin Concha Titiscania Limacina Bergh, 1890 En Colombia

Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras Boletín de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras ISSN 0122-9761 “José Benito Vives de Andréis” Bulletin of Marine and Coastal Research e-ISSN 2590-4671 49 (Supl. Esp.), 223-228 Santa Marta, Colombia, 2020 NOTA/NOTE Llenando un vacío: primer registro del gastrópodo neritáceo sin concha Titiscania limacina Bergh, 1890 en Colombia Filling a gap: first record of the shell-less neritacean gastropod Titiscania limacina Bergh, 1890 in Colombia Edgardo Londoño-Cruz 0000-0001-5762-9430 Grupo de Investigación en Ecosistemas Rocosos Intermareales y Submareales Someros (Lithos), Departamento de Biología, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. [email protected] RESUMEN l registro de la biodiversidad marina es una tarea fundamental y la distribución de las especies está en el centro de ella. Este documento corresponde al primer registro de Titiscania limacina, un neritaceo sin concha, en Colombia. Esta especie fue encontrada Een el intermareal de un ecosistema rocoso del Parque Nacional Natural Gorgona, en la costa Pacífica. Este descubrimiento llena un vacío en la distribución de la especie en el Pacífico Oriental Tropical y hace un llamado al monitoreo de la biodiversidad, lo cual puede, dado el potencial de esta costa colombiana poco estudiada, producir más e interesantes hallazgos de nuevas especies para la región, en particular, o para la ciencia, en general. PALABRAS CLAVE: Pacífico Oriental Tropical, isla Gorgona, babosa de mar ABSTRACT ecording marine biodiversity is a fundamental task and species distributions are at the very core of it. This paper is the first report of Titiscania limacina, a shell-less neritacean, in Colombia. -

Enidae, Griechischen Arten Der Napaeopsis Und (Gastropoda Pulmonata: Pupilloidea) Europäi- Leben, Liegt Die Vorliegende Bearb

BASTERIA, 56: 105-158, 1992 Notizen zur Familie Enidae, 4. Revision der griechischen Arten der Gattungen Ena, Zebrina, Napaeopsis und Turanena (Gastropoda Pulmonata: Pupilloidea) Ruud+A. Bank Crijnssenstraat 61hs, NL 1058 XV Amsterdam, Niederlande & Henk+P.M.G. Menkhorst Naturmuseum Rotterdam, Postfach 23452, NL 3001 KL Rotterdam, Niederlande Notes 4. Revision ofthe Greek of the on Enidae, species generaEna, Zebrina, Napaeopsis and Turanena (Gastropoda Pulmonata: Pupilloidea) As of revision of Greek land snails in and the Enidae a part a general family in particular, review of the Greek taxa of the and Turanena is a genera Ena, Zebrina, Napaeopsis presented. illustrated Twenty (sub)species are treated and (one ofTurkish origin only); four taxa are described science. Rhabdoena is considered of Zebrina. as new to a subgenus A type species is selected for the of Aschera; type species Napaeopsis is Buliminus merditanus and not Bulimus cefalonicus. The Caucasian Bulimus hohenackeri is not a representative ofNapaeopsis; it is provi- sionally placed underZebrina. An example of Hennig’s progression rule is found for three species of Zebrina (Rhabdoena). Lectotypes are selected for conemenosi [Ena], caesius [Zebrina], armenicus [Zebrina], ossicus discolor and Notes [Napaeopsis], [ Napaeopsis] carpathius [Turanena]. are given on some of the Eninae in erroneously reported taxa subfamily Greece. Bulimus corneus Deshayes and be of the Buliminus graecus appeared to representatives Bulimulidae and not of the Enidae. words: Key Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Enidae, Ena, Zebrina, Napaeopsis, Turanena, taxonomy, distribution,progression rule, Greece. Die Eniden-Fauna Griechenlands ist die reichsten differenzierte am des europäi- schen Festlands. Während in den meisten Ländern nicht mehr als 5-6 Arten leben, liegt die Zahl der Arten in Griechenland wahrscheinlich über 40. -

The Lower Pliocene Gastropods of Le Pigeon Blanc (Loire- Atlantique, Northwest France). Part 5* – Neogastropoda (Conoidea) and Heterobranchia (Fine)

Cainozoic Research, 18(2), pp. 89-176, December 2018 89 The lower Pliocene gastropods of Le Pigeon Blanc (Loire- Atlantique, northwest France). Part 5* – Neogastropoda (Conoidea) and Heterobranchia (fine) 1 2 3,4 Luc Ceulemans , Frank Van Dingenen & Bernard M. Landau 1 Avenue Général Naessens de Loncin 1, B-1330 Rixensart, Belgium; email: [email protected] 2 Cambeenboslaan A 11, B-2960 Brecht, Belgium; email: [email protected] 3 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, Netherlands; Instituto Dom Luiz da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal; and International Health Centres, Av. Infante de Henrique 7, Areias São João, P-8200 Albufeira, Portugal; email: [email protected] 4 Corresponding author Received 25 February 2017, revised version accepted 7 July 2018 In this final paper reviewing the Zanclean lower Pliocene assemblage of Le Pigeon Blanc, Loire-Atlantique department, France, which we consider the ‘type’ locality for Assemblage III of Van Dingenen et al. (2015), we cover the Conoidea and the Heterobranchia. Fifty-nine species are recorded, of which 14 are new: Asthenotoma lanceolata nov. sp., Aphanitoma marqueti nov. sp., Clathurella pierreaimei nov. sp., Clavatula helwerdae nov. sp., Haedropleura fratemcontii nov. sp., Bela falbalae nov. sp., Raphitoma georgesi nov. sp., Raphitoma landreauensis nov. sp., Raphitoma palumbina nov. sp., Raphitoma turtaudierei nov. sp., Raphitoma vercingetorixi nov. sp., Raphitoma pseudoconcinna nov. sp., Adelphotectonica bieleri nov. sp., and Ondina asterixi nov. sp. One new name is erected: Genota maximei nov. nom. is proposed for Pleurotoma insignis Millet, non Edwards, 1861. Actaeonidea achatina Sacco, 1896 is considered a junior subjective synonym of Rictaxis tornatus (Millet, 1854).