1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Project The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS the VREDEFORT DOME TEACHING US ABOUT the SEARCH for OTHER ERODED LARGE IMPACT STRUCTURES? Roger L

Bridging the Gap III (2015) 1045.pdf WHAT IS THE VREDEFORT DOME TEACHING US ABOUT THE SEARCH FOR OTHER ERODED LARGE IMPACT STRUCTURES? Roger L. Gibson, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, PO WITS, Johannesburg 2050, South Africa; [email protected]. Introduction: Vredefort has long been held to be extent of these breccias cannot be used as an indicator the oldest, largest and most deeply exhumed impact of the original limits of the impact structure. structure on Earth; however, in recent years its pre- With at least half the vertical extent of continental eminence in all three aspects has been challenged. crust typically being crystalline, a major problem may Evaluating the scientific debate around the claims of arise with trying to identify central uplifts on lithologi- the challengers [1,2,3] to these titles invokes a sense of cal or geophysical grounds; and traces of the wider déjà vu when one considers the decades-long history of crater dimensions are even less likely to be defined. debate about whether Vredefort itself originated by Age: The 2020 ± 5 Ma age of the Vredefort impact impact. This presentation briefly reviews the debate is based on U-Pb single-zircon geochronology of a around the impact-related features in the Vredefort variety of melt types. Dating of igneous zircons from Dome, with the main focus being the extent and inten- the impact-melt rock has been complemented by others sity of impact-induced thermal effects that play a sig- from voluminous pseudotachylitic breccias from the nificant role in masking potential diagnostic features. -

Defending Planet Earth: Near-Earth Object Surveys and Hazard Mitigation Strategies Final Report

PREPUBLICATION COPY—SUBJECT TO FURTHER EDITORIAL CORRECTION Defending Planet Earth: Near-Earth Object Surveys and Hazard Mitigation Strategies Final Report Committee to Review Near-Earth Object Surveys and Hazard Mitigation Strategies Space Studies Board Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. www.nap.edu PREPUBLICATION COPY—SUBJECT TO FURTHER EDITORIAL CORRECTION THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study is based on work supported by the Contract NNH06CE15B between the National Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the agency that provided support for the project. International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-XXXXX-X International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-XXXXX-X Copies of this report are available free of charge from: Space Studies Board National Research Council 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press, 500 Fifth Street, N.W., Lockbox 285, Washington, DC 20055; (800) 624-6242 or (202) 334-3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area); Internet, http://www.nap.edu. -

Structural Analysis of the Collar of the Vredefort Dome, South Africa— Significance for Impact-Related Deformation and Central Uplift Formation

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 40, Nr 9/10, 1537–1554 (2005) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Structural analysis of the collar of the Vredefort Dome, South Africa— Significance for impact-related deformation and central uplift formation Frank WIELAND, Roger L. GIBSON*, and Wolf Uwe REIMOLD Impact Cratering Research Group, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, P.O. Wits 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 25 October 2004; revision accepted 13 July 2005) Abstract–Landsat TM, aerial photograph image analysis, and field mapping of Witwatersrand supergroup meta-sedimentary strata in the collar of the Vredefort Dome reveals a highly heterogeneous internal structure involving folds, faults, fractures, and melt breccias that are interpreted as the product of shock deformation and central uplift formation during the 2.02 Ga Vredefort impact event. Broadly radially oriented symmetric and asymmetric folds with wavelengths ranging from tens of meters to kilometers and conjugate radial to oblique faults with strike-slip displacements of, typically, tens to hundreds of meters accommodated tangential shortening of the collar of the dome that decreased from ∼17% at a radius from the dome center of 21 km to <5% at a radius of 29 km. Ubiquitous shear fractures containing pseudotachylitic breccia, particularly in the metapelitic units, display local slip senses consistent with either tangential shortening or tangential extension; however, it is uncertain whether they formed at the same time as the larger faults or earlier, during the shock pulse. In addition to shatter cones, quartzite units show two fracture types—a cm- spaced rhomboidal to orthogonal type that may be the product of shock-induced deformation and later joints accomplishing tangential and radial extension. -

Once Upon a Purple Earth

Once Upon A Purple Earth With some scientists believing that the original life forms on our planet may have been purple, the search for life in other worlds may undergo some changes from the previous telltale markers, writes Fatima Sajid. Our planet has always been a special place — right from its formation to the time when single cells evolved into complex organisms, to the time of the dinosaurs and then humans populating the planet. It seems our planet was destined for life right from the beginning, with things happening at the right place at the right time. A new study carried out by a team of German scientists from the Institute for Planetary Research, at the Garman Centre for Air and Space Travel in Berlin, has shed some light on the early days of the earth. Geological records show that water in its liquid form was present on earth when it was just in its infancy, about 3.7 billion years ago. According to estimates, the earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old. This indicates that for water in its liquid form to be present, temperatures must have been above its freezing point. Their latest study has recently been published in the journal Planetary and Space Science. Warm and friendly How warm the temperature actually was, is still not known but one thing is almost certain — our friendly planet has been ice-free since it was very young. Latest research indicates that in its early days, our solar system was quite different from what we see or know today. -

Panspermia Theory E) Our Moon Results from a Giant Impact with « Theia », a Giant Asteroid

SEIS on Mars @ School : EGU GIFT 2016 : An example of hands-on activity focused on martian meteorite craters: for teachers … and for their pupils Diane Carrer Science teacher : Biology & geology teacher at: « Moutain’s High School » « Lycée de la Montagne », Valdeblore, Alpes Maritimes, France SEIS on Mars @ School : EGU GIFT 2016 : An example of hands-on activity focused on martian meteorite craters An investigation into the physics of meteorite crater formation Plan : 1. Why studying meteorites @ school ? 2. Link in between Meteorites Solar System ? 3. Link in between Meteorites Mars Exploration ? (InSight mission) ? 4. Let’s start 4 investigation experiments ! 5. Pedagogical exploitation: when Geosciences, Physics & mathematics have a « rendez-vous » … 1. Why studying meteorites @ school ? 5 good reasons to study meteorites a) Because it creates so nice geological objects on Earth: craters ! b) It is often seen as « bolides » …. And often on the press ! c) We (Mammals) are on Earth « thanks to » the -65 My meteorite (Chixculub) d) We (entire Biosphere) are on Earth thanks to meteorites: Panspermia theory e) Our Moon results from a giant impact with « Theia », a giant asteroid. 1. Why studying meteorites @ school ? a) Because it creates so nice geological objects : craters ! Namibia ROTER KAMM Crater 1. Why studying meteorites @ school ? a) Because it creates so nice geological objects : craters ! USA Meteor Crater 1. Why studying meteorites @ school ? a) Because it creates so nice geological objects : craters ! SOUTH AFRICA Vredefort Crater VREDEFORT ASTROBLEMA 2.023 Billion years (+/-4 My) 1. Why studying meteorites @ school ? Central peak Uplift (called Dome) SOUTH AFRICA COMPLEX IMPACT Vredefort Crater CRATER FORMATION 2.023 Billion years (+/-4 My) Impact Melt rocks 1. -

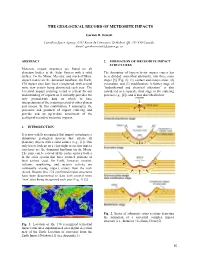

The Geological Record of Meteorite Impacts

THE GEOLOGICAL RECORD OF METEORITE IMPACTS Gordon R. Osinski Canadian Space Agency, 6767 Route de l'Aeroport, St-Hubert, QC J3Y 8Y9 Canada, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. FORMATION OF METEORITE IMPACT STRUCTURES Meteorite impact structures are found on all planetary bodies in the Solar System with a solid The formation of hypervelocity impact craters has surface. On the Moon, Mercury, and much of Mars, been divided, somewhat arbitrarily, into three main impact craters are the dominant landform. On Earth, stages [3] (Fig. 2): (1) contact and compression, (2) 174 impact sites have been recognized, with several excavation, and (3) modification. A further stage of more new craters being discovered each year. The “hydrothermal and chemical alteration” is also terrestrial impact cratering record is critical for our considered as a separate, final stage in the cratering understanding of impacts as it currently provides the process (e.g., [4]), and is also described below. only ground-truth data on which to base interpretations of the cratering record of other planets and moons. In this contribution, I summarize the processes and products of impact cratering and provide and an up-to-date assessment of the geological record of meteorite impacts. 1. INTRODUCTION It is now widely recognized that impact cratering is a ubiquitous geological process that affects all planetary objects with a solid surface (e.g., [1]). One only has to look up on a clear night to see that impact structures are the dominant landform on the Moon. The same can be said of all the rocky and icy bodies in the solar system that have retained portions of their earliest crust. -

The Threat of Centaurs for Terrestrial Planets and Their Orbital Evolution As Impactors

The threat of Centaurs for terrestrial planets and their orbital evolution as impactors M.A. Galiazzo1⋆ , E. A. Silber2 , R. Dvorak1 1Department of Astrophysics, University of Vienna, Turkenschantzstrasse 17, 1180, Vienna, Austria 2Department of Environmental, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Brown University, 324 Brook St., Providence, RI, 02912, USA ABSTRACT Centaurs are solar system objects with orbits situated among the orbits of Jupiter and Neptune. Centaurs represent one of the sources of Near-Earth Objects. Thus, it is crucial to understand their orbital evolution which in some cases might end in collision with terrestrial planets and produce catastrophic events. We study the orbital evolution of the Centaurs toward the inner solar system, and estimate the number of close encounters and impacts with the terrestrial planets after the Late Heavy Bombardment assuming a steady state population of Centaurs. We also estimate the possible crater sizes. We compute the approximate amount of water released: on the Earth, which is about 10−5 the total water present now. We also found sub-regions of the Centaurs where the possible impactors originate from. While crater sizes could extend up to hundreds of kilometers in diameter given the presently known population of Centaurs the majority of the craters would be less than ∼ 10 km. For all the planets and an average impactor size of ∼12 km in diameter, the average impact frequency since the Late Heavy Bombardment is one every ∼ 1.9 Gyr for the Earth and 2.1 Gyr for Venus. For smaller bodies (e.g. > 1 km), the impact frequency is one every 14.4 Myr for the Earth, 13.1 Myr for Venus and, 46.3 for Mars, in the recent solar system. -

A Tale of Clusters: No Resolvable Periodicity in the Terrestrial Impact Cratering Record

Meier & Holm-Alwmark, 2017 – A tale of clusters (accepted for publication in MNRAS) A tale of clusters: No resolvable periodicity in the terrestrial impact cratering record Matthias M. M. Meier1* and Sanna Holm-Alwmark2 1ETH Zurich, Institute of Geochemistry & Petrology, Clausiusstrasse 25, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland 2Department of Geology, Lund University, S olvegatan 12, 22362 Lund, Sweden * E-Mail: [email protected] Accepted 2017 January 23. Received 2017 January 18; in original form 2016 July 09. This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society following peer review. The version of record is available at: dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stx211 ABSTRACT Rampino & Caldeira (2015) carry out a circular spectral analysis (CSA) of the ter- restrial impact cratering record over the past 260 million years (Ma), and suggest a ~26 Ma periodicity of impact events. For some of the impacts in that analysis, new accurate and high-precision (“robust”; 2SE<2%) 40Ar-39Ar ages have recently been published, resulting in significant age shifts. In a CSA of the updated impact age list, the periodicity is strongly reduced. In a CSA of a list containing only im- pacts with robust ages, we find no significant periodicity for the last 500 Ma. We show that if we relax the assumption of a fully periodic impact record, assuming it to be a mix of a periodic and a random component instead, we should have found a periodic component if it contributes more than ~80% of the impacts in the last 260 Ma. -

The Impact Environment of the Hadean Earth

Chemie der Erde 73 (2013) 227–248 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Chemie der Erde jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.de/chemer Invited review The impact environment of the Hadean Earth a b c,d,e,∗ Oleg Abramov , David A. Kring , Stephen J. Mojzsis a United States Geological Survey, Astrogeology Science Center, 2255 North Gemini Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA b USRA – Lunar and Planetary Institute, Center for Lunar Science & Exploration, 3600 Bay Area Boulevard, Houston, TX 77058-1113, USA c University of Colorado, Department of Geological Sciences, NASA Lunar Science Institute, Center for Lunar Origin and Evolution (CLOE), 2200 Colorado Avenue, UCB 399, Boulder, CO 80309-0399, USA d Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon and Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Laboratoire de Géologie de Lyon, CNRS UMR 5276, 2 rue Raphael Dubois, Villeurbanne 69622, France e Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Research Center for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Institute for Geological and Geochemical Research, 45 Budaörsi ut, H-1112 Budapest, Hungary a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Impact bombardment in the first billion years of solar system history determined in large part the initial Received 1 July 2013 physical and chemical states of the inner planets and their potential to host biospheres. The range of Accepted 13 August 2013 physical states and thermal consequences of the impact epoch, however, are not well quantified. Here, we assess these effects on the young Earth’s crust as well as the likelihood that a record of such effects could be Keywords: preserved in the oldest terrestrial minerals and rocks. -

LIST of ASTROBLEMS/IMPATC STRUCTURES IDENTIFIED on EARTH SURFACE Third Edition of the Geological Map of the World, Sheet 1 Physi

LIST OF ASTROBLEMS/IMPATC STRUCTURES IDENTIFIED ON EARTH SURFACE Third edition of the Geological Map of the World, sheet 1 Physiography, volcanoes, astroblemes, at 1:50 000 000 - Compilator: Philippe Bouysse, 2006 Sources: 1. (Roman type) Site: <http://www.unb.ca/passc/ImpactDatabase>, April 2006 By John Spray & Jason Hines, Planetary And Space Science Centre (PASSC) University of New Brunswick, Canada (174 structures: number 1 to 174), 2. (Italics) Site: <http://www.somerikko.net/old/geo/imp/impacts.htm>, April 2006 By Jarmo Moilanen (Finland): Impact Structures of the World (since Nov. 1996) (21 structures: a to u) 3. (Bold) In addition: Velingara (Master, Diallo, Kande, Wade, 1999, South Africa/Senegal), Iturralde (T. J. Killeen, Missouri Botanical Garden, Saint Louis, 1995-2006) astroblems and Gilf Kebir impact crater field (Paillou et al., C. R. Géoscience, Paris, vol. 335, 2003). (3 structures) 4. (In red) Tunguska airblast TOTAL: 198 IMPACT STRUCTURES Nota: * = approximate central position DIAMETER N° CRATER NAME LOCATION LATITUDE LONGITUDE Age (Ma)* EXPOSED DRILLED (km) South Australia, 1 Acraman Australia S 32° 1' E 135° 27' 90 ~ 590 Y N a Alamo USA N 37°30' W 116°30' 190 367 - - 2 Ames Oklahoma, U.S.A. N 36° 15' W 98° 12' 16 470 ± 30 N Y 3 Amelia Creek Australia S 20° 55' E 134 ° 50' ~20 1640 - 600 Y N 4 Amguid Algeria N 26° 5' E 4° 23' 0.45 < 0.1 Y N 5 Aorounga Chad, Africa N 19° 6' E 19° 15' 12.6 < 345 Y N 6 Aouelloul Mauritania N 20° 15' W 12° 41' 0.39 3.0 ± 0.3 Y N 7 Araguainha Brazil S 16° 47' W 52° 59' 40 244.40 ± 3.25 Y N 8 Arkenu 1 Libya N 22° 4' E 23° 45' 6.8 < 140 Y N 9 Arkenu 2 Libya N 22° 4' E 23° 45' 10,3 < 140 Y N 10 Avak Alaska, U.S.A. -

Tuesday, July 30, 2013 POSTER SESSION I: SPECIAL SESSION IMPACT CRATERING — a PLANETARY PROCESS 7:00 P.M. Gallery at Enterprise Square

76th Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting (2013) sess307.pdf Tuesday, July 30, 2013 POSTER SESSION I: SPECIAL SESSION IMPACT CRATERING — A PLANETARY PROCESS 7:00 p.m. Gallery at Enterprise Square Garde A. A. Pattison J. Kokfelt T. McDonald I. Secher K. Impact-Triggered, Conduit-Type Ni-Cu Mineralisation, Norite Belt, Maniitsoq Structure, West Greenland [#5006] There are TWO different types of impact-related, magmatic Ni-Cu (-PGE) deposits: the upper-crustal Sudbury type exsolved from the impact melt sheet, and the lower-crustal Maniitsoq type exsolved from contaminated mantle melts. Scherstén A. Garde A. A. Complete Impact-Induced Hydrothermal Resetting of Magmatic Zircon, Maniitsoq Structure, West Greenland [#5007] This is possibly the first record ever of total, regional hydrothermal resetting of magmatic zircon. The 3000.9 ± 1.9 Ma age is interpreted as dating massive influx of (sea?) water into the giant impact structure immediately after the impacting. Keulen N. Garde A. A. Johansson L. Direct Mineral Melting in the Maniitsoq Structure, West Greenland [#5008] Microtextures of shock-melted minerals in the Maniitsoq structure constitute compelling evidence of impact-induced single mineral melting, and also document differential crustal reverberation during the solidification of each shock-melted phase. Buchner E. Schwarz W. H. Schmieder M. Trieloff M. Refined 40Ar/39Ar Ages for the Paasselkä (Finland) and Clearwater West (Canada) Impact Structures [#5009] Our newly obtained Ar-Ar plateau age for the Paasselkä impact (231.0 ± 1.7) confirms previous dating results with improved statistical robustness. The new age for Clearwater West (286.7 ± 1.2 Ma) refines earlier dating results for this impact event. -

LARGE METEORITE IMPACTS and Planetary EVOLUTION September 1-3,1997 Sudbury, Ontario CONFERENCE on LARGE METEORITE IMPACTS and PLANETARY EVOLUTION (SUDBURY1997)

NASA/CR- - 207991 BURY 1997 LARGE METEORITE IMPACTS AND PlANETARY EVOLUTION September 1-3,1997 Sudbury, Ontario CONFERENCE ON LARGE METEORITE IMPACTS AND PLANETARY EVOLUTION (SUDBURY1997) Hosted by Ontario Geological Survey Sponsored by Inco Limited Falconbridge Limited The Bamnger Crater Company Geological Survey of Canada Ontario Ministry of Northern Development and Mines Quebec Ministere des Ressources naturelles Lunar and Planetary Institute Scientific Organizing Committee A. Deutsch University ofMunster, Germany B. O. Dressier, Chair Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, Texas B. M. French Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC R. A. F. Grieve Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario G. W. Johns Ontario Geological Survey, Sudbury, Ontario V. L. Sharpton Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, Texas LPI Contribution No. 922 Compiled in 1997 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes, however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. Abstracts in this volume may be cited as Author A. B. (1997) Title of abstract. In Conference on Large Meteorite Impacts and Planetary Evolution (Sudbury 1997), p. XX, LPI Contribution No. 922, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. This volume is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113, USA Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost of shipping and handling. LPI Contribution No 922 ill Contents BP and Oasis Impact Structures, Libya, and Their Relation to Libyan Desert Glass: Petrography, Geochemistry, and Geochronology B.