Philharmonic Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 655. - 2 - March 2020 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Absil, Jean: Threne pour le Vendredi Saint/R.Bernier: Ode a unce Madone CULTURA 50679 A 10 (orch)/Feldbusch, Eric: 3 Poems of G.Lorca (narr, orch) - cond.de Haene, Ghyros , (Records International jacket) S 2 Alvarez Del Toro, Federico: Sinfonia "El Espiritu de la Tierra" (marimba & orch); ANGEL SAM 35080 A 25 Oratorio en la Cueva de la Marimba - cond.comp (gatefold) (p.1985) S 3 Alvarez del Toro, Federico: Gneiss (orch, 4 soli, tape); Ozomatli (voices, metal orch, DISCOS PUE DP. 1060 A 40 percussion & tape) - cond.comp S 4 Andriessen, Hendrik: Kuhnau Variations, Ricercare/L.Orthel: Sym 2 - Hague PO, PHILIPS A 2047 A 10 cond.Otterloo 5 Andriessen, Hendrik: Omaggio/Flothuis: Round/Straesser: Herfst/ Henkemans: DONEMUS DAVS 6903 A 10 Villonnerie/Kox: Cyclophony V - cond.Fournet, Nobel, Hupperts, Voorberg all live with scores S 6 Andriessen, Henrik: Sym 1/ Paap: Garlands of Music/ Horst: Reflexions Sonores - DONEMUS DAVS 6804 A 10 cond.Hupperts, Otterloo, Haitink all live with scores S 7 Andriessen, Jurriaan: Movimenti/ Delden: Piccolo Con/ Kox: Cyclofonie 1/ DONEMUS DAVS 6602 A 10 Badings: Sym 9 - cond.Rieu, Hupperts, Zinman all live with scores S 8 Andriessen, Jurriaan: Sym 4 (Aves)/Prokofiev: Lieutenant Kije Suite/Roussel: Rap PHILIPS D 88037 A 8 Flamande - cond.Hermans, Moonen (gatefold) 9 Andriessen, Louis: Nocturnen/Flothuis, Marius: Canti e Giuochi/Orthel, Leon: DONEMUS DAVS 6504 A 8 Scherzo II - E.Lugt sop, cond.Haitink, Jordans (complete score) 1965 10" 10 Badings: -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 650. - 2 - October 2019 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Absil: Clarinet Quartet/Pelemans, Willem: Clar Quartet/Cabus, Peter: Clar ZEPHYR Z 18 A 10 Quartet/Moscheles: Prelude et fugue - Belgian Clarinet Quartet (p.1982) S 2 Albrecht, Georg von: 2 Piano Sonatas; Prelude & Fugue; 3 Hymns; 5 Ostliche DA CAMERA SM 93141 A 8 Volkslieder - K.Lautner pno 1975 S 3 Alpaerts, Flor: James Ensor Suite/Mortelmans: In Memoriam/E.van der Eycken: DECCA 173019 A 8 Poeme, Refereynen - cond.Weemaels, Gras, Eycken S 4 Amelsvoort: 2 Elegies/Reger: Serenade/Krommer-Kramar: Partita EUROSOUND ES 46442 A 15 Op.71/Triebensee: Haydn Vars - Brabant Wind Ensemble 1979 S 5 Antoine, Georges: Pno Quartet Op.6; Vln Sonata Op.3 - French String Trio, MUSIQUE EN MW 19 A 8 Pludermacher pno (p.1975) S 6 Badings: Capriccio for Vln & 2 Sound Tracks; Genese; Evolutions/ Raaijmakers: EPIC LC. 3759 A 15 Contrasts (all electronic music) (gold label, US) 7 Baervoets: Vla Con/P.-B.Michel: Oscillonance (2 vlns, pno)/C.Schmit: Preludes for EMI A063 23989 A 8 Orch - Patigny vla, Pingen, Quatacker vln, cond.Defossez (p.1980) S 8 Baily, Jean: 3 Movements (hn, tpt, pf, string orch)/F.M.Fontaine: Concertino, DGG 100131 A 8 Fantasie symphonique (orch) - cond.Baily S 9 Balanchivadze: Pno Con 4 - Tcherkasov, USSR RTVSO, cond.Provatorov , (plain MELODIYA C10. 9671 A 25 Melodiya jacket) S 10 Banks, Don: Vln Con (Dommett, cond.P.Thomas)/ M.Williamson: The Display WORLD RECO S 5264 A 8 (cond.Hopkins) S 11 Bantock: Pierrot Ov/ Bridge: Summer, Hamlet, Suite for String Orch/ Butterworth: -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 627. - 2 - November 2017 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Absil: Sax Quartet/J.Rivier: Grave et presto/Francais: Serenade comique - Mule Sax DECCA LX 3142 A 25 EY2 Quartet (p.1955) 10" 2 Alfen: Midsummer's Virgil, The Mountain King - Royal Swedish Orch, cond.comp. TELEFUNKEN LA 33100 A 8 (black label) 1954 10" 3 Alfven, Hugo: Uppsalarapsodi/O.Lindberg: 3 Reiseerinnerungen/Udden: Lustspiel CUPOL CLPN 344 A 8 Ov/Wieslander: Unter/Atterberg: Ov/N.Eriksson: Serenade - Berlin Studio Orch, cond.S.Rybrant 1966, 1968 S 4 Antheil: Sonata (1951)/Absil: Contes/Honegger: Intrada/Genzmer: Konzertantes LAUREL LR 132 A 12 Duo - Gartner tr, Reid pno (p.1985) S 5 Avram, Ana Maria: Songs with bassoons; 3 Pno Pcs (comp.pno)/Irina Hasnas: SQ ELECTRECOR ST-ECE 3584 A 12 (Evolutio III); Melisme for pno S 6 Bacewicz: Vla Con; Con for 2 Pnos; In una parte - Kamas vla, Maksymuk, Witkowski MUZA SX 875 A 8 pno, cond.Wislocki S 7 Bargielski: 4 Duos - Bok basscl, Mair vibraphone, Kozlik accordeon, Riedhammer PRO VIVA ISPV 121 A 8 perc, Siwy Vln Duo, Pfeifer-Baranyi pno duo (p.1984) S 8 Bergman, Erik: SQ Op.98/K.Aho: SQ 3 - Sibelius SQ 1984 S FINLANDIA FAD 348 A 8 9 Boboc, Nicolae: Tara Halmagiului (Suite Sym); Tryptic; Divertimento - cond.comp. S ELECTRECOR ST-ECE 2590 A 10 10 Boerman, Jan: Composition (1972), Alchemie (1961), De Zee (all electronic) COMPOSERS' CV 7701 A 15 (booklet) (gatefold) S 11 Bogoslovsky: Vasiliy Terkin sym tale - Moscow RSO, cond.comp 10" MELODIYA D 15701 A 18 12 Britten: Our Hunting Fathers, Folksongs - Soderstrom, cond. -

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M. Jones, S.-J. Bradley, T. Lowe, A. Thwaite) Notes to performers by Matthew Jones Walton, Menuhin and ‘shifting’ performance practice The use of vibrato and audible shifts in Walton’s works, particularly the Violin Sonata, became (somewhat unexpectedly) a fascinating area of enquiry and experimentation in the process of preparing for the recording. It is useful at this stage to give some historical context to vibrato. As late as in Joseph Joachim’s treatise of 1905, the renowned violinist was clear that vibrato should be used sparingly,1 through it seems that it was in the same decade that the beginnings of ‘continuous vibrato use’ were appearing. In the 1910s Eugene Ysaÿe and Fritz Kreisler are widely credited with establishing it. Robin Stowell has suggested that this ‘new’ vibrato began to evolve partly because of the introduction of chin rests to violin set-up in the early nineteenth century.2 I suspect the evolution of the shoulder rest also played a significant role, much later, since the freedom in the left shoulder joint that is more accessible (depending on the player’s neck shape) when using a combination of chin and shoulder rest facilitates a fluid vibrato. Others point to the adoption of metal strings over gut strings as an influence. Others still suggest that violinists were beginning to copy vocal vibrato, though David Milsom has observed that the both sets of musicians developed the ‘new vibrato’ roughly simultaneously.3 Mark Katz persuasively posits the idea that much of this evolution was due to the beginning of the recording process. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8. -

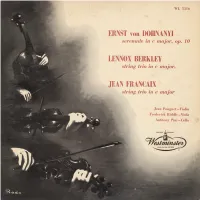

Serenade in E Major, Op. 10 / String Trio in C Major

NATURAL BALANCE LONG PLAYING RECORDS WL 5316 JEAN POUGNET Jean Pougnet was born in 1907. ERNST VON DOHNANYI He started to study the violin at age of 5, was taught by his sister for two years, then jor by Prof. Rowsby Woof, at age 11 entered Royal Academy of Music, winning three scholar- Serenade in © Major, Op. 10 ships in succession, until 1925. His first London recital age 15, first Promenade Concert, the next year subsequent experience with chamber music, solo playing, both for Music Societies, Public concerts and radio. At outbreak of war, undertook some special work for BBC until 1942, then joined LENNOX BERKELEY London Philharmonic Orchestra as concertmaster, in 1945 left the orchestra and has since concentrated on solo work. String Trio : FREDERICK CRAIG RIDDLE “Born in 1912 im Liverpool. Kent Scholar at Royal College of Music 1928-1933. Winner of Tagore Gold Medal 1933. Professor of viola at Royal College of Music. JEAN FRANCAIX Principal viola of the London Symphony Orchestra 1935-1938 and of London Philhar- monic Orchestra 1939-1952. String Trio in C Major ANTHONY PINI String C Trio, Ma Born in Buenos Aires. Came to England in 1912. ANTHONY PINI Has devoted much time to Chamber Music, co-founder of Philharmonia Quartet with Jean JEAN POUGNET FREDERICK RIDDLE Pougnet, Frederick Riddle and Henry Holst. Has played in most capitals of Europe as Violin Viola Cello soloist and toured America four times also with Sir Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He is Professor of cello Guildhall School of Music and Birming- The three string trios that comprise this recorded recital are each of them worthwhile ham College. -

Journal69-1.Pdf

October 1980, Number 69 The Delius Society Journal The Delius Society Journal October 1980,Number 69 The Delius Society Full Membership95.00 per year Studentsf2.50 USA and CanadaUS S10.00per year Subscription to Libraries (Journal only) f,3.50 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon D Mus, Hon D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLd Felix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland GibsonM Sc, Ph D (Founder Member) Sir Charles Groves CBE Stanford RobinsonOBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM Meredith DaviesMA, B Mus, FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon D Mus Vernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse, Mount Park Road, Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer P Lyons I Cherry Tree Close,St. Leonards-on-Sea,Sussex TH37 6EX Secretary Miss Estelle Palmley 22 Kinesbury Road, London NW9 ORR Editor StephenLloyd 4l MarlboroughRoad, Luton, BedfordshireLU3 IEF Tel: Luton (0582) 20075 Contents Editorial 3 ReginaldNettel: A PersonalMemoir by LewisForeman 7 Grez in Verse 8 Margot La Rouge: Part One by DavidEccott 9 DocumentingDelius: Part Two by RachelLowe 15 The 1980 Audio Awards by Gilbert Parfitt 20 Visit to Limpsfield by Estelle Palmley 2l Correspondence 22 Forthcoming Events 23 Cover lllustration An early sketch of Deliusby Edvard Munch reproducedby kind permissionof the Curator of the Munch Museum,Oslo, Norway. Additional copiesof this issue50p each,inclusive of postage. ISSNO3O64373 3 Editorial It is only appropriatethat the first words in this issueshould be oneswith which to expressour warmestthanks to the retiring editor, ChristopherRedwood, in appreciationof the continued excellenceof the Journal throughout the seven years of his editorship(incidentally the sameperiod of office as held by the previouseditor, John White).The twenty-sevenissues that he hasproduced have beena notableachievement. -

MELOS-ETHOS'97 INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY MUSIC November 7-16,1997 Bratislava

MELOS-ETHOS'97 INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC November 7-16,1997 Bratislava Member of the European Conference of Promoters of New Music 4tfl INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Member of the European Conference of Promoters of New Music 7-16 November 1997 Bratislava . ,"'".* tgf*' ^''fe lt 1 ff it;€*« The festival is supported by the Slovak Ministry of Culture and by KALEIDOSCOPE programme of the Commission of the European Communities The organizers express their warmest gratitude towards all institutions and companies !cr their support and assistance 'VnB ^ MAIN ORGANIZER National Music Centre - Slovkoncert Art Agency CO-ORGANIZERS Slovak Music Union Association of Slovak Composers Slovak Philharmonic Slovak Radio Music Fund WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF Institut Francais, Bratislava Association Francais d'Action Artistique (AFAA) Austrian Embassy, Bratislava Goethe-lnstitut, Bratislava United States Information Service, Bratislava The Czech Centre, Bratislava ISCM — Slovak Section The Polish institute, Bratislava Bulgarian Cultural and Information Centre, Bratislava Municipality of the Capital of the Slovak Republic Bratislava Istropolis, art and congress centre The Soros Center for Contemporary Arts Bratislava Open Society Fund Bratislava FESTIVAL COMMITTEE Vladimir Bokes (chairman) Juraj Benes Nada Hrckova Ivan Marton Peter Zagar Slavka Ferencova (festival secretary) FESTIVAL OFFICE & PRESS AND INFORMATION CENTRE National Music Centre Michalska 10 815 36 Bratislava 2nd floor No. 216 Tel/Fax +421 7 5331373 MobUe phone 0603 430336 iiJfS 4 "Am 1 •-"CERT CALEMDAR Friday • 7 November * 7.30 p.m p. 9 MoyzesHall SLOVAK SLNFONLETTA ZlLLNA JANUSZ POWOLNY conductor MAMMA WIESLER flute ZYGMUNT KRAUZE piano Salva, Knittel, Krauze, Mellnds, Adams Saturday • 8 November • 5.00 p.m. -

Hans Werner Henze 1

21ST CENTURY MUSIC DECEMBER 2012 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2012 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal. -

Spring 2018/3 by Brian Wilson and Dan Morgan

Second Thoughts and Short Reviews Spring 2018/3 By Brian Wilson and Dan Morgan Reviews are by Brian Wilson except where signed [DM] Spring 2018_1 is here and Spring 2018_2 here. Errata: Apologies for an incomplete link in Spring 2018_2: the link for the Bach keyboard music on Nimbus NI5948/49 takes you only to the main Wyastone page. The correct link is here. Remember to use the code MusicWeb10 for a 10% discount. Index BEETHOVEN String Quartet No.15_Sony BORGSTRÖM Violin Concerto (+ SHOSTAKOVICH)_BIS BRUCKNER Symphony No.7 (+ WAGNER Siegfried’s Funeral March) _DG DELIUS Piano Concerto (+ GRIEG)_Somm DYSON At the Tabard Inn – Overture; Symphony in G, etc._Chandos - St Paul’s Voyage to Melita, etc._Somm_Naxos FINZI Cello Concerto, LEIGHTON Suite Veris Gratia_Chandos GLUCK Heroes in Love_Glossa GRIEG Piano Concertos (+ DELIUS)_Somm HANDEL/HARTY Water Music Suite; Fireworks Suite_Past Classics LEIGHTON Suite Veris Gratia (+ FINZI)_Chandos MAHLER Symphony No.4_Pentatone MARTINŮ Double Concertos for Violin and Piano_Pentatone MONTEVERDI Vespro della Beata Vergine_PHI_Linn - Monteverdi in San Marco_Arcana PÄRT The Symphonies_ECM SAINT-SAËNS Piano Trios 1 and 2_Champs Hill SCHUBERT Piano Sonata No.21, Impromptus_Hyperion SHOSTAKOVICH Violin Concerto No.1 (+ BORGSTRÖM)_BIS STRAUSS (R) Also Sprach Zarathustra_Past Classics STROZZI Arias and Cantatas_Glossa SUK Asrael Symphony_SWR VASKS Laudate Dominum, etc._Ondine VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Piano Concerto, Oboe Concerto, Serenade to Music, Flos Campi_Chandos WAGNER Siegfried’s Funeral March – see Bruckner British Orchestral Premieres_Lyrita Gypsy Baroque_Alpha La Virtuosissima Cantatrice: Virtuoso and Bel Canto Masterpieces for Female Voice_Amon Ra *** Claudio MONTEVERDI (1567–1643) Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers, 1610) Dorothee Mields, Barbora Kabátková (soprano) Benedict Hymas, William Knight, Reinoud Van Mechelen, Samuel Boden (tenor) Peter Kooij, Wolf Matthias Friedrich (bass) Collegium Vocale Gent/Philippe Herreweghe rec. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 13 No. 2, 1997

JOURNAL ofthe AMERICAN ViOLA SOCIETY Section of THE INTERNATIONAL VIOLA SOCIETY Association for the Promotion ofViola Performance and Research Vol. 13 No.2 1997 OFFICERS Thomas Tatton President 7511 Park Woods Stockton, CA 95207 (209) 952-9367 Pamela Goldsmith Vice-President 11640 Amanda Drive Studio City, CA 91604 Donna Lively Clark Secretary jCFA, Butler University 4600 Sunset Indianapolis, IN 46208 Mary I Arlin Treasurer School ofMusic Ithaca College Ithaca, NY14850 Alan de Veritch Past President School ofMusic Indiana University Bloomington, IN 47405 BOARD Atar Arad Victoria Chiang Ralph Fielding john Graham Lisa Hirschmugl jerzy Kosmala jeffrey Irvine Patricia McCarty Paul Neubauer Karen Ritscher Christine Rutledge Pamela Ryan I I William Schoen _J I EDITOR, ]AVS ............~/. ._----- -"~j~~~ ! ___i David Dalton Brigham }Dung University Provo, UT 84602 PASTPRESIDENTS (1971-81) Myron Rosenblum -_._--------_.- ------------ Maurice W Riley (1981-86) David Dalton (1986-91) t=====~====---============-=======--==~ HONORARYPRESIDENT William Primrose (deceased) ~wSection of the Internationale Viola-Gesellschaft The Journal ofthe American Viola Society is a peer-reviewed publication ofthat organization and is produced at Brigham Young University, ©1985, ISSN 0898-5987. JAVSwelcomes letters and articles from its readers. Editorial Office: School ofMusic Harris Fine Arts Center Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 (801) 378-4953 Fax: (801) 378-5973 [email protected] Editor: David Dalton Associate Editor: David Day Assistant Editor for Viola Pedagogy: Jeffrey Irvine Assistant Editorfor Interviews: Thomas Tatton Production: Bryce Knudsen Advertising: Jeanette Anderson Advertising Office: Crandall House West (CRWH) 'Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 (801) 378-4455 [email protected] JAVS appears three times yearly. Deadlines for copy and artwork are March 1, July 1, and November 1; submissions should be sent to the editorial office. -

Klassisk Musik / Konstmusik Kulturbibliotekets Vinylsamling

Kulturbibliotekets vinylsamling: Klassisk musik / Konstmusik ABEL, Karl Friedrich (1723-1787) K 4612 Konsert för flöjt och orkester nr 1 C-dur (Wiesner - Knape) K 4612 Konsert för flöjt och orkester nr 2 e-moll (Wiesner - Knape) K 5606 Kvartett för oboe, violin, viola och violoncell A-dur (Feit - Trio à cordes M. de Paris) K 5606 Kvartett för oboe, violin, viola och violoncell G-dur (Feit - Trio à cordes M. de Paris) K 4612 Sinfonia nr 07 D-dur op.4:1 (Knape) K 4612 Sinfonia nr 17 C-dur op.7:5 (Knape) K 4612 Sinfonia nr 19 E-dur op.10:1 (Knape) ABRAHAM, Paul (1892-1960) K 4327 Blomman från Hawaii, operett - tvärsnitt (Schöner, Staal m.fl - dirigent okänd) K 3337 Viktorias husar, operett - tvärsnitt (Dellert, Funck, Wikström - Waldimir) K 4327 Viktorias husar, operett - tvärsnitt (Schöner, Staal m.fl - dirigent okänd) ABRAHAMSEN, Hans (f. 1952) K 6814 Walden för blåsare (Danska blåsarkvintetten) ACHATZ, Dag, piano K 4189 Ackompanjerar Birgit Finnilä, alt. Schumann, Vivaldi, Rangström mm. K 6571 Stravinsky: Våroffer i eget pianoarrangemang ADAM, Adolphe (1803-1856) K 3165 Giralda, uvertyr (Bonynge) K 1981 Giselle, balettmusik. Förkortad version (Karajan) K 1394 Giselle, balettmusik. Förkortad version (Martinon) K 2100 Giselle, balettmusik. Komplett (Bonynge) K 5307 Julsång "O holy night" (B. Nilsson, sopran) K 4804 Julsång "O holy night" (Döse, sopran) K 5696 Julsång "O holy night" (E. Hagegård, tenor) K 4803 Julsång "O holy night" (H. Hagegård, baryton) K 2698 Julsång "O holy night" (J. Björling, tenor) K 5795 Julsång "O holy night" (Mellnäs, sopran) K 2095 Julsång "O holy night" (Price, sopran) K 4809 Julsång "O holy night" (St.