Culture Plan for the Creative City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward City Charters in Canada

Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 34 Toronto v Ontario: Implications for Canadian Local Democracy Guest Editors: Alexandra Flynn & Mariana Article 8 Valverde 2021 Toward City Charters in Canada John Sewell Chartercitytoronto.ca Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp Part of the Law Commons Citation Information Sewell, John. "Toward City Charters in Canada." Journal of Law and Social Policy 34. (2021): 134-164. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp/vol34/iss1/8 This Voices and Perspectives is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Sewell: Toward City Charters in Canada Toward City Charters in Canada JOHN SEWELL FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS, there has been discussion about how cities in Canada can gain more authority and the freedom, powers, and resources necessary to govern their own affairs. The problem goes back to the time of Confederation in 1867, when eighty per cent of Canadians lived in rural areas. Powerful provinces were needed to unite the large, sparsely populated countryside, to pool resources, and to provide good government. Toronto had already become a city in 1834 with a democratically elected government, but its 50,000 people were only around three per cent of Ontario’s 1.6 million. Confederation negotiations did not even consider the idea of conferring governmental power to Toronto or other municipalities, dividing it instead solely between the soon-to-be provinces and the new central government. -

Toronto, Tourism, and the Fractured Gaze

PLACE MARKETING AND PLACE MAKING: TORONTO, TOURISM, AND THE FRACTURED GAZE by Nadia Franceschetti A thesis submitted to the Department of Cultural Studies In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2011) Copyright ©Nadia Franceschetti, 2011 Abstract This thesis is an empirical and theoretical investigation into the changing trends in place marketing as it relates to urban tourism, particularly in the city of Toronto. It begins by exploring broader discourses to do with capitalism and creativity and their impacts on city space and people’s interactions with it and within it. These perspectives are then situated in the Toronto context, a city that currently embraces the notion of the Creative City, as promulgated by Richard Florida, which encourages the branding of the city for the purpose of stimulated economic growth and in which tourism plays an increasing role. Thirdly, it examines the theoretical implications of the prominent belief that tourism and place marketing are imperative for Toronto’s economic well-being. Official efforts at place marketing and place branding construct what John Urry terms the tourist gaze, and frame the city in particular ways to particular people. Fourthly, this thesis gives an empirical account of how the gaze comes to bear on the physical city space in terms of infrastructure and financing projects in the interest of creating a Tourist City. The penultimate chapter brings to light how the rise of new media has allowed for the greater possibility to puncture the traditionally linear narrative of the city with new voices, thus fracturing the monolithic gaze in some instances. -

3. Description of the Potentially Affected Environment

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 3. Description of the Potentially Affected Environment The purpose of Chapter 3 is to present an overview of the environment potentially affected by the SWP to create familiarity with issues to be addressed and the complexity of the environment likely to be affected by the Project. All aspects of the environment within the Project Study Area (see Figure 2- 1 in Chapter 2) relevant to the Project and its potential effects have been described in this chapter. The chapter is divided into three sections which capture different components of the environment: 1. Physical environment: describes the coastal and geotechnical processes acting on the Project Study Area; 2. Natural environment: describes terrestrial and aquatic habitat and species; and, 3. Socio-economic environment: describes existing and planned land use, land ownership, recreation, archaeology, cultural heritage, and Aboriginal interests. The description of the existing environment is based on the information from a number of studies, which have been referenced in the relevant sections. Additional field surveys were undertaken where appropriate. Where applicable, future environmental conditions are also discussed. For most components of the environment, existing conditions within the Project Area or Project Study Area are described. Where appropriate, conditions within the broader Regional Study Area are also described. 3.1 Physical Environment Structures and property within slopes, valleys and shorelines may be susceptible to damage from natural processes such as erosion, slope failures and dynamic beaches. These processes become natural hazards when people and property locate in areas where they normally occur (MNR, 2001). Therefore, understanding physical natural processes is vital to developing locally-appropriate Alternatives in order to meet Project Objectives. -

Economic Development and Culture

OPERATING ANAL OPERATING ANALYST NOTES Contents I: Overview 1 II: Recommendations 4 III: 2014 Service Overview and Plan 5 IV: 2014 Recommended Total Operating Budget 15 V: Issues for Discussion 30 Appendices: 1) 2013 Service Performance 32 Economic Development and Culture 2) Recommended Budget by Expense Category 34 2014 OPERATING BUDGET OVERVIEW 3) Summary of 2014 Service Changes 37 What We Do 4) Summary of 2014 New Economic Development and Culture's (EDC) mission is to & Enhanced Service advance the City's prosperity, opportunity and liveability by Changes 38 creating a thriving environment for businesses and culture, as well as contribute to the City's economic growth and engage 5) Inflows/Outflows to / from Reserves & Reserve Funds 39 cultural expressions and experiences. 6) 2014 User Fee Rate 2014 Budget Highlights Changes 42 The total cost to deliver this Program to Toronto residents in 2014 is $69.127 million, offset by revenue of $20.634 million for a net cost of $48.493 million as shown below. Approved Recommended Change Contacts (In $000s) 2013 Budget 2014 Budget $% Gross Expenditures 63,430.7 69,126.6 5,695.8 9.0% Judy Skinner Gross Revenue 18,028.9 20,633.7 2,604.8 14.4% Manager, Financial Planning Net Expenditures 45,401.9 48,492.9 3,091.0 6.8% Tel: (416) 397‐4219 Moving into this year's budget EDC's 2014 Operating Budget Email: [email protected] provides funds for several new and enhanced initiatives, which are aligned with the City's purpose of delivering the Andrei Vassallo Pan Am 2015 games, as well as initiatives that are part of the Senior Financial Planning Culture Phase ‐In Plan to bring the City's spending in culture to Analyst $25 per capita. -

“Toronto Has No History!”: Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’S Largest City

Document généré le 2 oct. 2021 00:00 Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine “Toronto Has No History!” Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’s Largest City Victoria Freeman Encounters, Contests, and Communities: New Histories of Race and Résumé de l'article Ethnicity in the Canadian City En 1884, au cours d’une semaine complète d’événements commémorant le 50e Volume 38, numéro 2, printemps 2010 anniversaire de l’incorporation de Toronto en 1834, des dizaines de milliers de gens fêtent l’histoire de Toronto et sa relation avec le colonialisme et URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/039672ar l’impérialisme britannique. Une analyse des fresques historiques du défilé de DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/039672ar la première journée des célébrations et de discours prononcés par Daniel Wilson, président de l’University College, et par le chef de Samson Green des Mohawks de Tyendinaga dévoile de divergentes approches relatives à la Aller au sommaire du numéro commémoration comme « politique par d’autres moyens » : d’une part, le camouflage du passé indigène de la région et la célébration de son avenir européen, de l’autre, une vision idéalisée du partenariat passé entre peuples Éditeur(s) autochtones et colons qui ignore la rôle de ces derniers dans la dépossession des Indiens de Mississauga. La commémoration de 1884 marque la transition Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine entre la fondation du village en 1793 et l’incorporation de la ville en 1834 comme « moment fondateur » et symbole de la supposée « autochtonie » des ISSN colons immigrants. Le titre de propriété acquis des Mississaugas lors de l’achat 0703-0428 (imprimé) de Toronto en 1787 est jugé sans importance, tandis que la Loi d’incorporation 1918-5138 (numérique) de 1834 devient l’acte symbolique de la modernité de Toronto. -

Meadowcliffe Drive Erosion Control Project

Meadowcliffe Drive Erosion Control Project Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Environmental Study Report March 1, 2010 5 Shoreham Drive, Downsview, Ontario M3N 1S4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority gratefully acknowledges the efforts and contributions of the following people participating in the planning and design phases of the Meadowcliffe Drive Erosion Control Project: Al Sinclair Meadowcliffe Drive Resident Barbara Heidenreich Ontario Heritage Trust Beth McEwen City of Toronto Bruce Pinchin Shoreplan Engineering Limited Councilor Brian Ashton City of Toronto Councillor Paul Ainslie City of Toronto Daphne Webster Meadowcliffe Drive Resident David Argue iTransConsulting Limited Don Snider Meadowcliffe Drive resident Janet Sinclair Meadowcliffe Drive Resident Jason Crowder Terraprobe Limited Jim Berry Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Joe Delle Fave Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Joseph Palmissano iTransConsulting Limited Larry Field Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Laura Stephenson Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Lindsay Prihoda Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Lori Metcalfe Guildwood Village Community Association Mark Preston Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Mike Tanos Terraprobe Limited Moranne McDonnell Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Nancy Lowes City of Toronto Nick Saccone Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Patricia Newland Toronto and Region Conservation Authority Paul Albanese City of Toronto Peter Xiarchos M.P.P Lorenzo Berardinetti’s Office Susan Scinocca Meadowcliffe Drive Resident Sushaliya Ragunathan M.P.P Lorenzo Berardinetti’s Office Timo Puhakka Guildwood Village Community Association Trevor Harris Meadowcliffe Drive Resident Tudor Botzan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) continues to work towards ensuring healthy rivers and shorelines, greenspace and biodiversity, and sustainable communities. -

Heritage Property Research and Evaluation Report

ATTACHMENT NO. 10 HERITAGE PROPERTY RESEARCH AND EVALUATION REPORT WILLIAM ROBINSON BUILDING 832 YONGE STREET, TORONTO Prepared by: Heritage Preservation Services City Planning Division City of Toronto December 2015 1. DESCRIPTION Above: view of the west side of Yonge Street, north of Cumberland Street and showing the property at 832 Yonge near the south end of the block; cover: east elevation of the William Robinson Building (Heritage Preservation Services, 2014) 832 Yonge Street: William Robinson Building ADDRESS 832 Yonge Street (west side between Cumberland Street and Yorkville Avenue) WARD Ward 27 (Toronto Centre-Rosedale) LEGAL DESCRIPTION Concession C, Lot 21 NEIGHBOURHOOD/COMMUNITY Yorkville HISTORICAL NAME William Robinson Building1 CONSTRUCTION DATE 1875 (completed) ORIGINAL OWNER Sleigh Estate ORIGINAL USE Commercial CURRENT USE* Commercial * This does not refer to permitted use(s) as defined by the Zoning By-law ARCHITECT/BUILDER/DESIGNER None identified2 DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION Brick cladding with brick, stone and wood detailing ARCHITECTURAL STYLE See Section 2.iii ADDITIONS/ALTERATIONS See Section 2. iii CRITERIA Design/Physical, Historical/Associative & Contextual HERITAGE STATUS Listed on City of Toronto's Heritage Register RECORDER Heritage Preservation Services: Kathryn Anderson REPORT DATE December 2015 1 The building is named for the original and long-term tenant. Archival records indicate that the property, along with the adjoining site to the south was developed by the trustees of John Sleigh's estate 2 No architect or building is identified at the time of the writing of this report. Building permits do not survive for this period and no reference to the property was found in the Globe's tender calls 2. -

Schedule 4 Description of Views

SCHEDULE 4 DESCRIPTION OF VIEWS This schedule describes the views identified on maps 7a and 7b of the Official Plan. Views described are subject to the policies set out in section 3.1.1. Described views marked with [H] are views of heritage properties and are specifically subject to the view protection policies of section 3.1.5 of the Official Plan. A. PROMINENT AND HERITAGE BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES & LANDSCAPES A1. Queens Park Legislature [H] This view has been described in a comprehensive study and is the subject of a site and area specific policy of the Official Plan. It is not described in this schedule. A2. Old City Hall [H] The view of Old City hall includes the main entrance, tower and cenotaph as viewed from the southwest and southeast corners at Temperance Street and includes the silhouette of the roofline and clock tower. This view will also be the subject of a comprehensive study. A3. Toronto City Hall [H] The view of City Hall includes the east and west towers, the council chamber and podium of City Hall and the silhouette of those features as viewed from the north side of Queen Street West along the edge of the eastern half of Nathan Phillips Square. This view will be the subject of a comprehensive study. A4. Knox College Spire [H] The view of the Knox College Spire, as it extends above the roofline of the third floor, can be viewed from the north along Spadina Avenue at the southeast corner of Bloor Street West and at Sussex Avenue. A5. -

Canadian Version

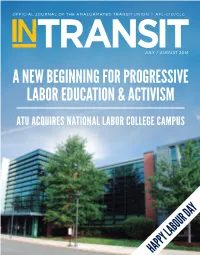

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE AMALGAMATED TRANSIT UNION | AFL-CIO/CLC JULY / AUGUST 2014 A NEW BEGINNING FOR PROGRESSIVE LABOR EDUCATION & ACTIVISM ATU ACQUIRES NATIONAL LABOR COLLEGE CAMPUS HAPPY LABOUR DAY INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS LAWRENCE J. HANLEY International President JAVIER M. PEREZ, JR. NEWSBRIEFS International Executive Vice President OSCAR OWENS TTC targets door safety woes International Secretary-Treasurer Imagine this: your subway train stops at your destination. The doors open – but on the wrong side. In the past year there have been INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS 12 incidents of doors opening either off the platform or on the wrong side of the train in Toronto. LARRY R. KINNEAR Ashburn, ON – [email protected] The Toronto Transit Commission has now implemented a new RICHARD M. MURPHY “point and acknowledge” safety procedure to reduce the likelihood Newburyport, MA – [email protected] of human error when opening train doors. The procedure consists BOB M. HYKAWAY of four steps in which a subway operator must: stand up, open Calgary, AB – [email protected] the window as the train comes to a stop, point at a marker on the wall using their index finger and WILLIAM G. McLEAN then open the train doors. If the operator doesn’t see the marker he or she is instructed not to open Reno, NV – [email protected] the doors. JANIS M. BORCHARDT Madison, WI – [email protected] PAUL BOWEN Agreement in Guelph, ON, ends lockout Canton, MI – [email protected] After the City of Guelph, ON, locked out members of Local 1189 KENNETH R. KIRK for three weeks, city buses stopped running, and transit workers Lancaster, TX – [email protected] were out of work and out of a contract while commuters were left GARY RAUEN stranded. -

Postcard from Plaguetown: SARS and the Exoticization of Toronto Carolyn Strange

12 Postcard from Plaguetown: SARS and the Exoticization of Toronto Carolyn Strange ‘“Bad news travels like the plague. Good news doesn’t travel well”’. While this epigram might have appeared in an advertising or marketing textbook, they were the words a Canadian politician chose to explain why the federal government sponsored a Toronto rock concert in the summer of 2003. As the Senator stated, 3.5 million dollars was a small price to pay for an event held to restore confidence in a city struck by SARS. The virus – first diag- nosed in Toronto in March 2003 – had already claimed 42 lives; interna- tional media coverage of the outbreak had strangled the economy. While public health officials imposed quarantine and isolation measures to combat the spread of SARS bureaucrats and business leaders were equally active, treating the virus as an economic crisis caused by negative publicity. ‘SARSstock’, as locals dubbed the concert, was one of many events pre- scribed to repair and revitalize the city’s image post-SARS. By drawing close to half a million fans with big name musicians, including The Rolling Stones, it provided Canadian and US newspapers and television outlets with a splashy ‘good news’ item. Local media commented that the concert gave Torontonians a much-needed tonic. As the Toronto Star declared, it proved to the world that ‘life and business here rock on’.1 When the World Health Organization (WHO) issued its advisory against ‘unnecessary travel’ to Toronto in April 2003, not only suspected SARS car- riers but the city itself felt borders close around it, cutting off vital flows of traffic to the city.2 It is thus possible to frame the economic consequences of SARS within the longer history of quarantine, cordons sanitaires and their commercial dimensions (as Hooker also argues in Chapter 10). -

Renaming to the Toronto Zoo Road

Councillor Paul Ainslie Constituency Office, Toronto City Hall Toronto City Council Scarborough Civic Centre 100 Queen Street West Scarborough East - Ward 43 150 Borough Drive Suite C52 Scarborough, Ontario M1P 4N7 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Chair, Government Management Committee Tel: 416-396-7222 Tel: 416-392-4008 Fax: 416-392-4006 Website: www.paulainslie.com Email: [email protected] Date: October 27, 2016 To: Chair, Councillor Chin Lee and Scarborough Community Council Members Re: Meadowvale Road Renaming between Highway 401 and Old Finch Road Avenue Recommendation: 1. Scarborough Community Council request the Director, Engineering Support Services & Construction Services and the Technical Services Division begin the process to review options for the renaming of Meadowvale Road between Highway 401 and Old Finch Avenue including those of a "honourary" nature. 2. Staff to report back to the February 2017 meeting The Toronto Zoo is the largest zoo in Canada attracting thousands of visitors annually becoming a landmark location in our City. Home to over 5,000 animals it is situated in a beautiful natural habitat in one of Canada's largest urban parks. Opening its doors on August 15, 1974 the Toronto Zoo has been able to adapt throughout the years developing a vision to "educate visitors on current conservation issues and help preserve the incredible biodiversity on the planet", through their work with endangered species, plans for a wildlife health centre and through their Research & Veterinary Programs. I believe it would be appropriate to introduce a honourary street name for the section of Meadowvale Road between Highway 401 and Old Finch Avenue to recognize the only public entrance to the Toronto Zoo. -

Ontario Media Development Corporation

ONTARIO MEDIA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Year in Review 2012-2013 Ontario’s Creative Industries: GROWING. THRIVING. LEADING. We’ve got it going Ontario Media Development Corporation Board of Directors Kevin Shea, Chair Anita McOuat Owner and President Senior Manager, Audit and SheaChez Inc. Assurance Group PwC Nyla Ahmad Vice-President, New Venture Operations Marguerite Pigott & Strategic Partnerships Head of Creative Development Rogers Communications Inc. Super Channel Principal Paul Bronfman Megalomedia Productions Inc. Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Comweb Group Inc. and Justin Poy William F. White International President and Creative Director Chairman The Justin Poy Agency Pinewood Toronto Studios Inc. Robert Richardson Alexandra Brown President Alex B. & Associates Devon Group Susan de Cartier Mark Sakamoto President Principal Starfish Entertainment Sakamoto Consulting Inc. Nathon Gunn John B. Simcoe CEO Partner Bitcasters PwC CEO Social Game Universe Nicole St. Pierre Head of Business and Legal Affairs Leesa Levinson Mercury Filmworks Executive Director Lights, Camera, Access! Blake Tohana Chief Financial Officer and Sarah MacLachlan Chief Operating Officer President marblemedia House of Anansi Press and Groundwood Books Ildiko Marshall Former Vice-President and Publisher Today’s Parent Group at Rogers Publishing Ontario Media Development Corporation (OMDC) 175 Bloor Street East, South Tower, Suite 501 Toronto, Ontario M4W 3R8 www.omdc.on.ca Published by the Government of Ontario © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013 Disponible en français l Printed on recycled paper Table of Contents What We Do and How We Do It ...............2 Message from the Chair and the President & Chief Executive Officer .........3 The Creative Industries ...........................4 Building New Our Mission: Platforms for Success ............................6 Collaboration and The Ontario Media Development Cross-Sector Partnerships .......................8 Corporation is the central catalyst for Ontario’s Creative Media in the Global Marketplace ...................