Archaeological Discoveries Along the Farningham to Hadlow 2008-09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Knoll IGHTHAM • KENT

The Knoll IGHTHAM • KENT • cheshire • sk11 9aq E • C U • P w The Knoll COMMON ROAD • IGHTHAM • KENT • TN15 9DY A most impressive late Victorian country house with annexe potential set within glorious secluded grounds on the edge of popular Ightham village Entrance Vestibule • Reception Hall • Drawing Room • Dining Room • Sitting Room • Orangery Games Room • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Secondary Kitchen • Utility Room • Two Cloakroom Basement: Playroom • Boiler Room Master Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom • Six Further Bedrooms Jack and Jill Bathroom • Family Bathroom • Shower Room. All Weather Tennis Court • Heated Swimming Pool Detached Double Garage • Pool House • Stables and Tack Room Formal Gardens • Grounds and Woodland EPC’s = D In Total 5.8 Acres Savills Sevenoaks 74 High Street Sevenoaks Kent TN13 1JR [email protected] 01732 789 700 Description The Knoll is a substantial detached property believed to date from the late 1800s with a later extension. Internally, the elegant and well proportioned accommodation is presented to a high standard throughout and arranged over three floors. The property has the benefit of a self contained annexe if required although it is currently incorporated within the main house. The elevations are red brick and tile hung, enhanced with stone mullioned windows and quoins, all under a tiled pitched roof. The established gardens and grounds are a delightful feature of the property with a heated swimming pool and all weather tennis court in the grounds. • Internal features include high ceilings with cornicing, brass finger plates, handles and switch plates and limestone, oak and parquet flooring. • The well proportioned principal reception rooms include an elegant drawing room with a Chesney's fireplace, window seating and a wonderful vista over the grounds to the rear. -

Oaklodge, Botsom Lane, West Kingsdown, Sevenoaks, Kent

Oaklodge, Botsom Lane, West Kingsdown, Sevenoaks, Kent Oaklodge Botsom Lane, West Kingsdown, Sevenoaks, Outside To the front of the property, there is a paved Kent TN15 6BN area for parking and a pathway leads to the side entrance. Raised planters, are painted white and A contemporary three bedroom contain architectural shrubs and miniature trees, property, with low-maintenance creating interest in the front garden. To the rear, garden, in a wooded semi-rural setting. there is an area of paved terracing adjoining the living room, with a pathway leading to the end of the garden, where a raised platform provides Reception hall | Open-plan Kitchen/Dining/ an additional outdoor dining and relaxation Sitting area | Principal bedroom with en suite area, beneath a timber gazebo. Further raised bathroom | 2 Further bedrooms | Family planters are an attractive addition to the central bathroom | Balcony | Garden | Shed | Off-road ‘green’ area and a garden shed provides useful parking | EPC rating C storage. The property Skilfully designed for ultimate use of space, Oaklodge provides a home with ultra- modern interiors and offers light and airy accommodation across two floors. The entrance doorway is located on the side of the house, giving access to a hallway which leads through to the open-plan kitchen and living space, featuring a vaulted ceiling. Fitted with modern white and grey units and incorporating Bosch appliances, the kitchen also has an island unit with a breakfast bar. There is an area currently designated to dining and beyond this a seating area, which is positioned beside a wall of glass, comprising bi-fold doors and window panels to the ceiling which, together with four skylights, allow natural light to flood the room. -

Bluewater to West Kingsdown / West Kingsdown to Bluewater

West Kingsdown to Dartford 429 Via Farningham, Swanley, Joyden's Wood, Bexley Park & Wilmington Monday to Friday School School School Days Days Holidays West Kingsdown, Portobello 0600 0640 0727 - 0727 0930 1030 1130 1230 1330 1430 1645 1745 West Kingsdown, Hever Road Shops 0603 0643 0730 - 0730 0933 1033 1133 1233 1333 1433 1648 1748 Farningham, The Pied Bull 0607 0647 0734 - 0734 0937 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1652 1752 Swanley Station, Azalea Drive 0618 0658 0745 0732 0745 0948 1048 1148 1248 1348 1448 1703 1803 Swanley High Street 0620 0700 0747 0734 0747 0950 1050 1150 1250 1350 1450 1705 1805 Swanley Asda 0622 0702 0749 0736 0749 0952 1052 1152 1252 1352 1452 1707 1807 Swanley, St Mary's Road - - 0751 0738 0751 0954 1054 1154 1254 1354 1454 1709 1809 Swanley, Brook Road - - 0755 0742 0755 0958 1058 1158 1258 1358 1458 1713 1813 White Oak Estate - - 0759 0746 0759 1002 1102 1202 1302 1402 1502 1717 1817 Joyden's Wood Estate - - 0807 0754 0807 1010 1110 1210 1310 1410 1510 1725 1825 Bexley Park - - 0810 0757 0810 1013 1113 1213 1313 1413 1513 1728 1828 Leyton Cross - - 0813 0800 0813 1016 1116 1216 1316 1416 1516 1731 1831 Wilmington, Orange Tree - - 0816 0803 0816 1019 1119 1219 1319 1419 1519 1734 1834 Leigh Academy (Park Road) - - - 0811 - - - - - - - - - Dartford, Instone Road - - - - 0819 1022 1122 1222 1322 1422 1522 1737 1837 Dartford Grammar Schools - - 0826 - - - - - - - - - - Dartford Station, Home Gardens - - 0830 - 0821 1024 1124 1224 1324 1424 1524 1739 1839 Saturdays West Kingsdown, Portobello 0830 0930 1030 1130 1230 -

DA03 - Sevenoaks Rural North

B.3 DA03 - Sevenoaks Rural North 2012s6728 - Sevenoaks Stage 1 SWMP (v1.0 Oct 2013) VI Sevenoaks Stage 1 SWMP: Summary Sheet Drainage Area 03: Sevenoaks Rural North Area overview Area (km2) 102 Drainage assets/systems Type Known Issues/problems Responsibility There are records of sewer flooding linked to Thames Sewer networks Sewer ( foul and surface water) Thames Water Water systems Watercourses Main River Known fluvial issues associated with the Main Rivers Environment Agency Known fluvial issues associated with ordinary Kent County Council and Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River watercourses. Sevenoaks District Council Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Riparian Flood risk Receptor Source Pathway Historic Evidence Recorded flooding from the River Darent in 1969 Reports describe medieval brick River Darent culverts under old houses on Cray Heavy rainfall resulting in Road. The culverts are unable to surface water run off and Unnamed Drain (Cray Road) take peak flows and floods occur in overloaded sewers. the car park and in some Sewers (Cray Road and Crockenhill) commercial properties. Repeated Surface water (blocked drains / A: Crockenhill flooding from Thames Water gullies) Cray Road, Eynsford Road, Church Road, Crockenhill sewers on Cray Road (1996, 1997, Lane, Seven Acres and Woodmount 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009) Fluvial Flow routes have been highlighted where natural valleys Regular surface water flooding has formed in the topography, from Highcroft through the east been reported at Eynsford Road, of Crockenhill towards Swanley to the north. Church Road, Crockenhill Lane, Seven Acres and Woodmount Records of the River Darent in Sep- 69, Sep-71 and Sep-72. -

The Farningham & Eynsford Local History Society

The Farningham & Eynsford Local History Society Founded 1985 A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee No. 5620267 incorporated the 11th November 2005 Registered Charity 1113765 (Original Society founded 1985 Registered Charity no 1047562) Bulletin No 113 March 2017 Annual General Meeting The AGM will take place at Eynsford Village Hall on Friday 19th May (doors open 7.30pm) The Agenda will be as follows 1 Welcome 5 Setting of subscriptions Level of 2017 2 Apologies for absence 6 Election of Officers and Committee 3 Minutes of last AGM/ 7 The future of the Society Matters arising 8 Any other business 4 Adoption of accounts If you would like information about the History Society Committee, please call Barbara Cannell for further information. Should you decide to put yourself forward for election to the committee nominations must be with the Chairman before the AGM commences on 19th May 2017 Forthcoming Talks and Events Date Details Where 19th May AGM - Transportation in our villages, road, rail and air (display of items from the FELHS collection) EVH EVH 8th July Eynsford Shops Exhibition – display of photographs and memorabilia related to local shops over the years (11am – 4pm The Library, Castle Hotel, Eynsford) 6th September Visit to Gravesend/Tilbury Fort (full details to follow) 22nd September Charles Darwin – Toni Mount EVH 30th September Eliott Downs Till Remembered – A display of photographs and information relating to the life of Eliott Downs Till who died 100 years ago, on 30th September 1917 (11am – 4pm The Library, Castle Hotel, Eynford) 17th November George Bernard Shaw, Playing the Clown – Brian FVH Freeland Unless otherwise stated all Meetings are held on a Friday evening from 730pm, talk commencing 8pm. -

Ightham Mote Circular Walk to Old Soar Manor

Ightham Mote circular walk to Old Ightham Mote, Mote Road, Ivy Soar Manor Hatch, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN15 0NT Admire the Kentish countryside as you enjoy this circular walk TRAIL linking two of our places dating Walking to medieval England. The walk takes you through the ancient GRADE woodland of Scathes Wood, into Easy the Fairlawne Estate and onto Plaxtol Spout before returning to DISTANCE Ightham Mote through orchards Approximately 7 miles and the Greensand Way. (11.3 km) TIME approximately 4 4.5 Terrain hours, including a 30 A mixture of footpaths, woodland, country lanes and meadows, with approximately 12 stiles on route. minutes stop over at Old Soar Manor Things to see OS MAP OS Explorer map 147 grid ref: TQ584535 Contact 01732 810378 [email protected] Scathes Wood Old Soar Manor Shipbourne Church Facilities Still known locally as Scats Wood, Old Soar Manor is the remaining The church of St Giles was built it is mainly sweet chestnut with structure of a rare, late 13th- by Edward Cazalet of Fairlawne some oak. There is a wonderful century knight's dwelling, and opened in 1881. display of bluebells in early including the solar chamber, spring. barrel-vaulted undercroft chapel and garderobe. nationaltrust.org.uk/walks Ightham Mote, Mote Road, Ivy Hatch, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN15 0NT Start/end Start: Ightham Mote visitor reception grid ref TQ584535 End: Ightham Mote visitor reception, grid ref TQ584535 How to get there By bus: Nu-Venture 404 from Sevenoaks, calls Thursday and 1. From Ightham Mote Car Park (with Visitor Reception behind you), walk through the walled car park and up the entrance driveway to a five-bar gate and stile on the right, which is the entrance to Friday only, on other days alight Scathes Wood. -

Draft Local Plan Site Appraisals

Draft Local Plan Site Appraisals Blue Category Draft Local Plan “Blue” Sites The following sites have been placed in the “blue” category because they are too small to accommodate at least 5 housing units: Site Ref Site Address HO108 Redleaf Estate Yard, Camp Hill, Chiddingstone Causeway HO11 Land rear of 10-12 High Street, Seal HO113 Bricklands, Morleys Road, Sevenoaks Weald HO116 Fonthill, Chevening Road, Chipstead HO122 Heverswood Lodge, High Street, Eynsford HO142 Heathwood, Castle Hill, Hartley HO155 Oaklands, London Road, West Kingsdown HO168 Land rear of Olinda, Ash Road, Hartley HO172 Stanwell House, Botsom Lane, West Kingsdown HO174 Land south of Heaverham Road, Kemsing HO207 Land fronting 12-16 Church Lane, Kemsing HO209 Open space at Spitalscross Estate, Fircroft Way, Edenbridge HO21 Land rear of Ardgowan, College Road, Hextable HO229 Land east of Fruiterers Cottages, Eynsford Road, Crockenhill HO241 Land between The Croft and the A20, Swanley HO251 Warren Court Farm and adjoining land, Knockholt Road, Halstead HO256 Land south of Lane End, Sparepenny Lane, Eynsford HO265 101 Brands Hatch Park, Scratchers Lane, Fawkham HO267 Land east of Greatness Lane, Sevenoaks HO269 Land south of Seal Road, Sevenoaks HO270 59 High Street, Westerham HO275 The Croft, Bradbourne Vale Road, Sevenoaks HO29 Land West of 64 London Road, Farningham HO303 Ballantrae and land to the rear, Castle Hill, Hartley HO314 Garages west of Oakview Stud Farm, Lombard Street, Horton Kirby HO320 Land at Slides Farm, North Ash Road, New Ash Green HO324 78 Main Road, Hextable HO337 Windy Ridge and land to the rear, Church Road, Hartley HO34 The Rising Sun and Car Park, Twitton Lane, Otford HO341 Plot 4. -

STATUTORY CONSULTATION – MINOR ON-STREET PARKING PROPOSALS EYNSFORD, FARNINGHAM, OTFORD, SEVENOAKS and SWANLEY Sevenoaks Join

STATUTORY CONSULTATION – MINOR ON-STREET PARKING PROPOSALS EYNSFORD, FARNINGHAM, OTFORD, SEVENOAKS AND SWANLEY Sevenoaks Joint Transportation Board – 13 September 2016 Report of Chief Officer, Environmental and Operational Services Status: For Decision Key Decision: No Executive Summary: The consideration of the results of the statutory consultation regarding minor on-street parking proposals for locations in Eynsford, Farningham, Otford, Sevenoaks and Swanley, within The Kent County Council (Various Roads in the District of Sevenoaks) (Prohibition and Restriction of Waiting and Loading and Unloading and On-Street Parking Places)(Amendment 19) Order 2016 This report supports the Key Aim of • Caring Communities • Sustainable Economy Portfolio Holder Cllr. Dickins Contact Officer Jeremy Clark Recommendation to Sevenoaks Joint Transportation Board: (a) the results of the statutory consultation in respect of the parking proposals and the Officer comments/recommendations given in Appendices 1 to 5 be noted; (b) since no objections were received in respect of the Eynsford (Birch Close) parking proposals shown in Appendix 1 and described in the table in paragraph 14 of the report, it be noted that these will be implemented as drawn; (c) the objections received to the Farningham (High Street) parking proposals shown in Appendix 2 and described in the table in paragraph 20 of the report be upheld in part, and the parking proposals be implemented over the extent drawn, but reduced from double yellow lines to a single yellow line, prohibiting parking -

JBA Consulting

B.2 DA02 - Tonbridge and Malling Rural Mid 2012s6726 - Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP (v1.0 October 2013) v Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP: Summary and Actions Drainage Area 02: Tonbridge and Malling Rural Mid Area overview Area (km2) 83.2 Drainage assets/systems Type Known Issues/problems Responsibility Southern Water and Thames Water Sewer (foul and surface water Sewer networks There are issues linked with Southern Water systems. (latter very small portion in NW (Ightham, Addington)) corner of drainage area) Known fluvial issues associated with the River Bourne at Watercourses Main River Environment Agency Borough Green. Known fluvial issues associated with ordinary watercourses in Ightham, Nepicar Oast, Ryarsh, Borough Kent County Council and Tonbridge Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River Green, Birling, Birling Ashes Hermitage and St Leonard's and Malling Borough Council Street. Lower Medway Internal Drainage Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Board Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Riparian Flood risk Receptor Source Pathway Historic Evidence Records of regular flooding affecting the road and National Trust land Heavy rainfall resulting in A: Mote Road Mote Road surface water run off FMfSW (deep) indicates a flow route following the ordinary watercourse, not explicitly affecting the road. Flooding along Redwell Lane is a regular problem and recently in 2012 sandbags were needed to deflect water. Records of flooding Redwell Lane, Old Lane and Tunbridge Road along Old Lane appear to be Heavy rainfall resulting in isolated to 2008, although the road FMfSW (deep) also indicates Old Lane as a pathway B: Ightham Common surface water run off and was recorded as repeatedly flooded overloaded sewers over several weeks. -

The Farningham & Eynsford Local History Society

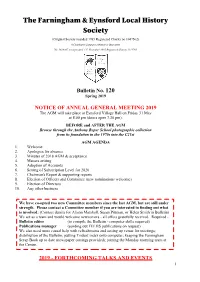

The Farningham & Eynsford Local History Society (Original Society founded 1985 Registered Charity no 1047562) A Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee No. 5620267 incorporated 11th November 2005 Registered Charity 1113765 Bulletin No. 120 Spring 2019 NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2019 The AGM will take place at Eynsford Village Hall on Friday 31 May at 8.00 pm (doors open 7.30 pm). BEFORE and AFTER THE AGM Browse through the Anthony Roper School photographic collection from its foundation in the 1970s into the C21st AGM AGENDA 1. Welcome 2. Apologies for absence 3. Minutes of 2018 AGM & acceptance 4. Matters arising 5. Adoption of Accounts 6. Setting of Subscription Level for 2020 7. Chairman's Report & supporting reports 8. Election of Officers and Committee (new nominations welcome) 9. Election of Directors 10. Any other business We have co-opted two new Committee members since the last AGM, but are still under strength. Please contact a Committee member if you are interested in finding out what is involved: (Contact details for Alison Marshall, Susan Pittman, or Helen Smith in Bulletin) We act as a team and would welcome newcomers - all offers gratefully received. Required - Bulletin editor (to compile the Bulletin - computer skills required) Publications manager (sending out FELHS publications on request) We also need more casual help with refreshments and setting up venue for meetings; distribution of the Bulletin; putting Trident index onto computer; keeping the Farningham Scrap Book up to date (newspaper cuttings provided); joining the Monday morning team at the Centre. 2019 - FORTHCOMING TALKS AND EVENTS 1 2019 Doors open at 7.30 pm for talks at 8.00 pm. -

Kent County Council

March 2018 Kent County Council Flood Investigation Report Flooding affecting the areas of Borough Green Road and Busty Lane, Ightham On the 25th June 2016 This document has been prepared by Kent County Council Flood and Water Management Team as the Lead Local Flood Authority under Section 19 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010, with the assistance of: • Kent County Council Highways, Transportation and Waste • Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council • Ightham Parish Council • Kent Fire and Rescue Service • Local Residents and Landowners The findings in this report are based on the information available to KCC at the time of preparing the report. KCC expressly disclaim responsibility for any error in or omission from this report. KCC does not accept any liability for the use of this report or its contents by any third party. For further information or to provide comments, please contact us at [email protected] Document Status: Issue Revision Description Date 0 0 Draft Report for Internal Comment 31 Jan 2017 0 1 Draft Report for External Comment 9 Mar 2017 0 2 Final Draft for External comment 13 Mar 2017 1 0 ISSUE FOR PARISH / TMBC COMMENT 20 Mar 2017 1 0 PUBLISHED 20 Mar 2018 www.kent.gov.uk Investigation of Flooding affecting the areas of Borough Green Road and Busty Lane on 25th June 2016 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Requirement for Investigation ............................................................................................... -

Ightham Mote: Topographical Analysis of the Landscape

8 IGHTHAM MOTE: TOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF THE LANDSCAPE Matthew Johnson, Timothy Sly, Carrie Willis1 Abstract. This chapter reports on survey at Ightham Mote in 2013 and 2014, and puts the survey results in the context of a wider analysis of the Ightham landscape. Ightham is another late medieval building surrounded by water features, whose setting might be seen as a ‘designed landscape’. Here, we outline and evaluate the evidence for the landscape as it developed through time. As with the other buildings and landscapes discussed in this volume, rather than argue for either an exclusively utilitarian or exclusively aesthetic view, we provide an alternative framework with which to explore the way that barriers and constraints on movement in physical space reflect boundaries in social space. Rather than labelling a landscape aesthetic or practical, we can identify the practices and experiences implicated in landscapes, and their active role in social relations. Ightham Mote is the fourth late medieval building and landscape to be discussed in this volume (Fig. 8.1; for location see Fig. 1.1). Like the others, Ightham is a National Trust property. The buildings consist of an inner and outer court, whose ‘footprint’ and external appearance was probably substantially complete by the end of the Middle Ages. The standing structure is a patchwork of different building phases from the early 14th century to the present day. Most recently, the building went through a comprehensive conservation programme costing over ten million pounds, and involving the controlled disassembly and reconstruction of large parts of the house. The information revealed by this process enabled others to put together a very detailed outline of the development of the house from Fig.