Ightham Mote: Topographical Analysis of the Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NHS West Kent

NHS West Kent CCG - Dispensing Practices Dispensing at this Practice Name Main site premises? Address Post Code Amherst Medical Amherst Medical Practice* Y No * Practice 21 St Botolphs Road Sevenoaks Kent TN13 3AQ Amherst Medical Practice N Yes Brasted Surgery High Street Brasted Kent TN16 1HU Edenbridge Dr Bayley T R L & Partners Y Yes Medical Station Road Edenbridge Kent TN8 5ND Greggs Wood Medical Centre do not dispense at this site Y No Medical Centre Greggs Wood Road Tunbridge Wells Kent TN2 3JL Greggs Wood Medical Centre N Yes The Old Bakery Penshurst Road Speldhurst Kent TN3 0PE The Hildenborough Medical Hildenborough Hildenborough Group Y Yes Medical Centre Westwood Tonbridge Road Kent TN11 9HL Hildenborough Medical Group do not dispense at this site N No The Surgery Morleys Road Weald Kent TN14 6QX Hildenborough Medical Group do not dispense at Rear Of Leigh High Street this site N No The Surgery Village Hall Leigh Tonbridge Kent TN11 8RL Hildenborough Medical Group do not dispense at The Trenchwood 264 Shipbourne this site N No Medical Centre Road Tonbridge Kent TN10 3ET North Ridge North Ridge Rye Dr Player P V & Partners Y Yes Medical Practice Road Hawkhurst Cranbrook, Kent TN18 4EX Dr Howitt A J & Partners do not dispense at this site Y No Warders East Street Tonbridge Kent TN9 1LA Dr Howitt A J & Partners N Yes The Surgery Village Hall Penshurst Tonbridge Kent TN11 8BP Bearsted Medical Dr Moss M L & Partners Y Yes Practice Yeoman Lane Bearsted Kent ME14 4DS Winterton Surgery do not dispense at this site Y No Winterton Surgery -

The Knoll IGHTHAM • KENT

The Knoll IGHTHAM • KENT • cheshire • sk11 9aq E • C U • P w The Knoll COMMON ROAD • IGHTHAM • KENT • TN15 9DY A most impressive late Victorian country house with annexe potential set within glorious secluded grounds on the edge of popular Ightham village Entrance Vestibule • Reception Hall • Drawing Room • Dining Room • Sitting Room • Orangery Games Room • Kitchen/Breakfast Room • Secondary Kitchen • Utility Room • Two Cloakroom Basement: Playroom • Boiler Room Master Bedroom with En Suite Bathroom • Six Further Bedrooms Jack and Jill Bathroom • Family Bathroom • Shower Room. All Weather Tennis Court • Heated Swimming Pool Detached Double Garage • Pool House • Stables and Tack Room Formal Gardens • Grounds and Woodland EPC’s = D In Total 5.8 Acres Savills Sevenoaks 74 High Street Sevenoaks Kent TN13 1JR [email protected] 01732 789 700 Description The Knoll is a substantial detached property believed to date from the late 1800s with a later extension. Internally, the elegant and well proportioned accommodation is presented to a high standard throughout and arranged over three floors. The property has the benefit of a self contained annexe if required although it is currently incorporated within the main house. The elevations are red brick and tile hung, enhanced with stone mullioned windows and quoins, all under a tiled pitched roof. The established gardens and grounds are a delightful feature of the property with a heated swimming pool and all weather tennis court in the grounds. • Internal features include high ceilings with cornicing, brass finger plates, handles and switch plates and limestone, oak and parquet flooring. • The well proportioned principal reception rooms include an elegant drawing room with a Chesney's fireplace, window seating and a wonderful vista over the grounds to the rear. -

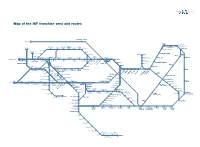

IKF ITT Maps A3 X6

51 Map of the IKF franchise area and routes Stratford International St Pancras Margate Dumpton Park (limited service) Westcombe Woolwich Woolwich Abbey Broadstairs Park Charlton Dockyard Arsenal Plumstead Wood Blackfriars Belvedere Ramsgate Westgate-on-Sea Maze Hill Cannon Street Erith Greenwich Birchington-on-Sea Slade Green Sheerness-on-Sea Minster Deptford Stone New Cross Lewisham Kidbrooke Falconwood Bexleyheath Crossing Northfleet Queenborough Herne Bay Sandwich Charing Cross Gravesend Waterloo East St Johns Blackheath Eltham Welling Barnehurst Dartford Swale London Bridge (to be closed) Higham Chestfield & Swalecliffe Elephant & Castle Kemsley Crayford Ebbsfleet Greenhithe Sturry Swanscombe Strood Denmark Bexley Whitstable Hill Nunhead Ladywell Hither Green Albany Park Deal Peckham Rye Crofton Catford Lee Mottingham New Eltham Sidcup Bridge am Park Grove Park ham n eynham Selling Catford Chath Rai ngbourneT Bellingham Sole Street Rochester Gillingham Newington Faversham Elmstead Woods Sitti Canterbury West Lower Sydenham Sundridge Meopham Park Chislehurst Cuxton New Beckenham Bromley North Longfield Canterbury East Beckenham Ravensbourne Brixton West Dulwich Penge East Hill St Mary Cray Farnigham Road Halling Bekesbourne Walmer Victoria Snodland Adisham Herne Hill Sydenham Hill Kent House Beckenham Petts Swanley Chartham Junction uth Eynsford Clock House Wood New Hythe (limited service) Aylesham rtlands Bickley Shoreham Sho Orpington Aylesford Otford Snowdown Bromley So Borough Chelsfield Green East Malling Elmers End Maidstone -

Ightham Mote Circular Walk to Old Soar Manor

Ightham Mote circular walk to Old Ightham Mote, Mote Road, Ivy Soar Manor Hatch, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN15 0NT Admire the Kentish countryside as you enjoy this circular walk TRAIL linking two of our places dating Walking to medieval England. The walk takes you through the ancient GRADE woodland of Scathes Wood, into Easy the Fairlawne Estate and onto Plaxtol Spout before returning to DISTANCE Ightham Mote through orchards Approximately 7 miles and the Greensand Way. (11.3 km) TIME approximately 4 4.5 Terrain hours, including a 30 A mixture of footpaths, woodland, country lanes and meadows, with approximately 12 stiles on route. minutes stop over at Old Soar Manor Things to see OS MAP OS Explorer map 147 grid ref: TQ584535 Contact 01732 810378 [email protected] Scathes Wood Old Soar Manor Shipbourne Church Facilities Still known locally as Scats Wood, Old Soar Manor is the remaining The church of St Giles was built it is mainly sweet chestnut with structure of a rare, late 13th- by Edward Cazalet of Fairlawne some oak. There is a wonderful century knight's dwelling, and opened in 1881. display of bluebells in early including the solar chamber, spring. barrel-vaulted undercroft chapel and garderobe. nationaltrust.org.uk/walks Ightham Mote, Mote Road, Ivy Hatch, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN15 0NT Start/end Start: Ightham Mote visitor reception grid ref TQ584535 End: Ightham Mote visitor reception, grid ref TQ584535 How to get there By bus: Nu-Venture 404 from Sevenoaks, calls Thursday and 1. From Ightham Mote Car Park (with Visitor Reception behind you), walk through the walled car park and up the entrance driveway to a five-bar gate and stile on the right, which is the entrance to Friday only, on other days alight Scathes Wood. -

Freehold for Sale

DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY WITH PLANNING CONSENT FOR 3x1 BED UNITS FREEHOLD FOR SALE est.1828 bracketts 65 SHIPBOURNE ROAD, TONBRIDGE, KENT, TN10 3ED FREEHOLD FOR SALE BUILDING FOR CONVERSION AND EXTENSION TO PROVIDE 3x1 BEDROOM UNITS 65 SHIPBOURNE ROAD TONBRIDGE KENT TN10 3ED brackettsest.1828 132 High Street Tonbridge Kent TN9 1BB Tel: (01732) 350503 Fax: (01732) 359754 E-mail: [email protected] www.bracketts.co.uk Also at 27-29 High Street, Tunbridge Wells, Kent Tel: (01892) 533733 LOCATION TITLE NUMBER VIEWING AND FURTHER INFORMATION Situated on the western side of Shipbourne Road Freehold title number K214736. around 0.5 miles to the north of the town centre Copies of plans, planning consent, and reports and 1 mile from the mainline station. can be viewed at the following Drop Box link or FOR SALE be provided upon request from Bracketts. The A21 is around 5 miles providing a dual carriageway link to junction 5 of the M25 at Freehold for sale with vacant possession. https://www.dropbox.com/sh/k14cftjc19n8l4m/A Sevenoaks. ACMOQQMfG7UnJZ-ZrM8ckwxa?dl=0 PRICE Viewing strictly by appointment through sole DESCRIPTION Unconditional offers invited in the range agents Bracketts – 01732 350503. £175,000-£200,000 for the freehold Comprises a late Victorian/early Edwardian two interest. Contact: Jeffrey Moys storey commercial building to be sold with the NO VAT. Email: [email protected] benefit of planning consent for conversion and an additional floor to provide three one bedroom Or John Giblin units. SERVICES Email: [email protected] Prospective purchasers shall satisfy themselves November 2019 FLOOR AREA with regards to the adequacy of mains services. -

Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Local Plan 2011-2031 Regulation 19 Publication Version Representation Form

Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Local Plan 2011-2031 Regulation 19 Publication Version Representation Form Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council respects your privacy and is committed to protecting your personal data. Further details of our Privacy Notice following the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation can be found on our website: www.tmbc.gov.uk/privacy-notice-localplan Ref: A (For office use only) Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Local Plan 2011-2031 Regulation 19 Publication Version – Representation Form Please return by 4pm on Monday 19th November 2018 to: [email protected] or by post to: Planning Policy Manager, Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council, Gibson Building, Gibson Drive, Kings Hill, West Malling, Kent ME19 4LZ This form has two parts: Part A – Personal Details Part B – Your representation(s). Please fill in a separate sheet for each representation you wish to make. Please see guidance note at the back of the form for definitions and details. 1. Personal Details * 2. Agent’s Details (if applicable) Title MRS First Name SARAH Last Name HUSEYIN Job Title PARISH CLERK (where relevant) Organisation SHIPBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL representing (where relevant) Address Line 1 GABLE COTTAGE Address Line 2 ISMAYS ROAD Address Line 3 IGHTHAM Postal Town SEVENOAKS Post Code TN15 9BE Telephone Number 10732 886402 Email Address [email protected] * If an agent is appointed, please complete only the Title, Name and Organisation boxes above in 1 but complete the full contact details of the agent in 2. Please note: Where an email address is given, this will be used as the primary means of contact. -

Meadow Place Upper Green Road, Shipbourne, Tonbridge, Kent, TN11 9PG

Meadow Place Upper Green Road, Shipbourne, Tonbridge, Kent, TN11 9PG An attractive, extended Colt 4.3 miles), Borough Green (4.4 miles) and Sevenoaks (7 miles). Borough Green serves House with permission to London Victoria in about 50 minutes, whilst Hildenbroough and Sevenoaks serve Charring extend further on a generous Cross, via London Bridge and Waterloo East, and plot of about 3/4 of an acre, Cannon Street with journey time of around 35 minutes (from Sevenoaks). located just off The Common The M25 is also within easy reach, which in turn in this popular village gives access to London, Gatwick and Heathrow Airports, Bluewater shopping centre near Dartford and the Channel Tunnel terminus. Guide Price £1,225,000 The area is well supplied with highly-regarded state and private schools including Walthamstow Hall, Sevenoaks (secondary) School, Solefields, Granville and New Beacon preparatory schools in Summary Sevenoaks. There is also St Michaels & Russell o Reception Hall House preparatory schools in Otford and Combe o Sitting Room Bank School for Girls in Sundridge. There are boys o Dining Room/Study and girls grammar schools in nearby Tonbridge o Kitchen/Breakfast Room and Tunbridge Wells. Shpibourne itself boasts an o Guest Bedroom/Family Room excellent primary school. o Utility Room o Cloakroom Sevenoaks boasts Wildernesse and Knole golf o 4 Bedrooms clubs and Nizels in Hildenborough is also nearby. o 3 Bath/Shower Rooms There is a sports and leisure centre in Sevenoaks o W.C. and a private health/fitness centre at Nizels. Cricket and Rugby are played and enjoyed at The o Garden Stores/Workshop/Summerhouse Vine in Sevenoaks. -

NEWSLETTER PAROCHIAL CHURCH COUNCIL Secretary: Mrs C Chambers 382228 Treasurer: Mr P Sandland 07866 588856 Deanery Synod Rep: Mr N Ward 810525

OFFICERS OF ST GILES AND VILLAGE ORGANISATIONS ST GILES Rector of Shipbourne with Plaxtol: 811081 Rev Dr Peter Hayler Email: [email protected] The Rectory, The Street, Plaxtol TN15 0QG http://shipbourne.com/st-giles-church/ St Giles and Shipbourne Lay Reader Mr P Brewin 810361 Churchwardens: Ms C Jackson 07729814798 Mr A Boorman 352597 NEWSLETTER PAROCHIAL CHURCH COUNCIL Secretary: Mrs C Chambers 382228 Treasurer: Mr P Sandland 07866 588856 Deanery Synod Rep: Mr N Ward 810525 CHURCH OFFICERS Parish Safeguarding Officers: Ms C Jackson 07729814798 Miss G Coates (children) 811432 Choirmaster: Mr J Young 810289 Electoral Roll: Mr A Boorman 352597 Flower Guild Mrs F Ward 810525 Bell Ringing Sir Paul Britton 365794 SHIPBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL Parish Clerk: Sarah Huseyin 886402 [email protected] Chair: Nick Tyler 811079 Councillors: S Oram V Redman P Leach J Sheldrick, J Bate VILLAGE WEBSITE www.shipbourne.com SHIPBOURNE SCHOOL Head: Mrs Daters 810344 www.shipbourne.kent.sch.uk SHIPBOURNE VILLAGE HALL Chairman: Curtis Galbraith 763637 Bookings: Helen Leach 811144 SHIPBOURNE FARMERS’ MARKET Manager: Bob Taylor 833976 SHIPBOURNE WI President Barbara Jones 811152 [email protected] SHIPBOURNE CRICKET CLUB Secretary: Mark Fenton 811067 PLAXTOL & SHIPBOURNE TENNIS CLUB Membership: Cilla Langdon-Down 810338 ST GILES’ AND SHIPBOURNE NEWSLETTER Editor: Lindsay Miles 810439 [email protected] Advertising: Lindsay Miles 810439 [email protected] Copying: Mary Perry 810797 January 2021 USEFUL POLICE CONTACT NUMBERS -

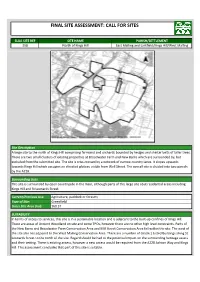

Final Site Assessment: Call for Sites

FINAL SITE ASSESSMENT: CALL FOR SITES SLAA SITE REF SITE NAME PARISH/SETTLEMENT 358 North of Kings Hill East Malling and Larkfield/Kings Hill/West Malling Site Description A large site to the north of Kings Hill comprising farmland and orchards bounded by hedges and shelter belts of taller trees. There are two small clusters of existing properties at Broadwater Farm and New Barns which are surrounded by, but excluded from the submitted site. The site is criss-crossed by a network of narrow country lanes. It slopes upwards towards Kings Hill which occupies an elevated plateau visible from Well Street. The overall site is divided into two parcels by the A228. Surrounding Uses This site is surrounded by open countryside in the main, although parts of this large site abut residential areas including Kings Hill and St Leonards Street. Current/Previous Use: Agriculture, paddock or forestry Type of Site: Greenfield Gross Site Area (ha): 160.37 SUITABILITY In terms of access to services, this site is in a sustainable location and is adjacent to the built-up confines of Kings Hill. There are areas of Ancient Woodland on site and some TPOs, however there are no other high level constraints. Parts of the New Barns and Broadwater Farm Conservation Area and Mill Street Conservation Area fall within the site. The west of the site also lies adjacent to the West Malling Conservation Area. There are a number of Grade 1 Listed Buildings along St. Leonards Street to the north of the site. Regard should be had to the potenital impact on the surrounding heritage assets and their setting. -

JBA Consulting

B.2 DA02 - Tonbridge and Malling Rural Mid 2012s6726 - Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP (v1.0 October 2013) v Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP: Summary and Actions Drainage Area 02: Tonbridge and Malling Rural Mid Area overview Area (km2) 83.2 Drainage assets/systems Type Known Issues/problems Responsibility Southern Water and Thames Water Sewer (foul and surface water Sewer networks There are issues linked with Southern Water systems. (latter very small portion in NW (Ightham, Addington)) corner of drainage area) Known fluvial issues associated with the River Bourne at Watercourses Main River Environment Agency Borough Green. Known fluvial issues associated with ordinary watercourses in Ightham, Nepicar Oast, Ryarsh, Borough Kent County Council and Tonbridge Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River Green, Birling, Birling Ashes Hermitage and St Leonard's and Malling Borough Council Street. Lower Medway Internal Drainage Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Board Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Riparian Flood risk Receptor Source Pathway Historic Evidence Records of regular flooding affecting the road and National Trust land Heavy rainfall resulting in A: Mote Road Mote Road surface water run off FMfSW (deep) indicates a flow route following the ordinary watercourse, not explicitly affecting the road. Flooding along Redwell Lane is a regular problem and recently in 2012 sandbags were needed to deflect water. Records of flooding Redwell Lane, Old Lane and Tunbridge Road along Old Lane appear to be Heavy rainfall resulting in isolated to 2008, although the road FMfSW (deep) also indicates Old Lane as a pathway B: Ightham Common surface water run off and was recorded as repeatedly flooded overloaded sewers over several weeks. -

Local Plan DRAFT

ANNEX 1 Tonbridge & Malling Borough Council Local Plan DRAFT Regulation 19 Pre-Submission Publication June 2018 Foreword The Borough of Tonbridge and Malling is a diverse and characterful place. It includes areas of recent development and growth together with historic environments. Its geography is varied and the physical characteristics have and will continue to reflect patterns of land use and activity. It is a place where traditional and modern businesses thrive, where established and new communities have flourished but where pressures on community facilities, transport infrastructure and the environment are challenging. The Borough Council, working with a wide range of partners, have embraced the benefit of strategic planning over decades. That has been beneficial in shaping development and properly addressing needs for homes, jobs and supporting facilities in a planned way. Moving forward the continuation of that approach is ever more challenging, but in providing a sustainable and planned approach to our borough and providing for local needs this Plan takes on that challenge. This Local Plan relates closely to the borough and communities it will serve. It reflects national planning policy and shapes that locally, based on what is seen locally as the most important planning issues taking account of locally derived evidence. It is designed as a plan that is responsible in facing up to difficult choices and one which is based upon fostering care in the way we plan for this and future generations of Tonbridge and Malling. It provides a sound basis on which to judge planning applications, achieve investment and provide confidence about future development and future preservation where both are appropriate. -

Kent County Council

March 2018 Kent County Council Flood Investigation Report Flooding affecting the areas of Borough Green Road and Busty Lane, Ightham On the 25th June 2016 This document has been prepared by Kent County Council Flood and Water Management Team as the Lead Local Flood Authority under Section 19 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010, with the assistance of: • Kent County Council Highways, Transportation and Waste • Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council • Ightham Parish Council • Kent Fire and Rescue Service • Local Residents and Landowners The findings in this report are based on the information available to KCC at the time of preparing the report. KCC expressly disclaim responsibility for any error in or omission from this report. KCC does not accept any liability for the use of this report or its contents by any third party. For further information or to provide comments, please contact us at [email protected] Document Status: Issue Revision Description Date 0 0 Draft Report for Internal Comment 31 Jan 2017 0 1 Draft Report for External Comment 9 Mar 2017 0 2 Final Draft for External comment 13 Mar 2017 1 0 ISSUE FOR PARISH / TMBC COMMENT 20 Mar 2017 1 0 PUBLISHED 20 Mar 2018 www.kent.gov.uk Investigation of Flooding affecting the areas of Borough Green Road and Busty Lane on 25th June 2016 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Requirement for Investigation ...............................................................................................