Balikbayan Boxes As Metaphors for Filipino American (Dis)Location"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiating Care Across Borders &Generations: an Analysis of Care

Negotiating Care Across Borders & Generations: An Analysis of Care Circulation in Filipino Transnational Families in the Chubu Region of Japan by MCCALLUM Derrace Garfield DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Development GRADUATE SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NAGOYA UNIVERSITY Approved by the Dissertation Committee: ITO Sanae (Chairperson) HIGASHIMURA Takeshi KUSAKA Wataru Approved by the GSID Committee: March 4, 2020 This dissertation is dedication to Mae McCallum; the main source of inspiration in my life. ii Acknowledgements Having arrived at this milestone, I pause to reflect on the journey and all the people and organizations who helped to make it possible. Without them, my dreams might have remained unrealized and this journey would have been dark, lonely and full of misery. For that, I owe them my deepest gratitude. First, I must thank the families who invited me into their lives. They shared with me their most intimate family details, their histories, their hopes, their joys, their sorrows, their challenges, their food and their precious time. The times I spent with the families, both in Japan and in the Philippines, are some of the best experiences I have ever had and I will forever cherish those memories. When I first considered the possibility of studying the family life of Filipinos, I was immediately daunted by the fact that I was a total stranger and an ‘outsider’, even though I had already made many Filipino friends while I was living in Nagano prefecture in Japan. Nevertheless, once I made the decision to proceed and started approaching potential families, my fears were quickly allayed by the warmth and openness of the Filipino people and their willingness to accept me into their lives, their families and their country. -

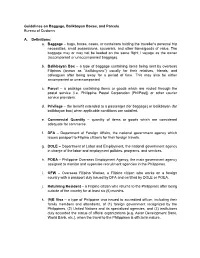

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs

Guidelines on Baggage, Balikbayan Boxes, and Parcels Bureau of Customs A. Definitions: a. Baggage – bags, boxes, cases, or containers holding the traveller’s personal trip necessities, small possessions, souvenirs, and other items/goods of value. The baggage may or may not be loaded on the same flight / voyage as the owner (accompanied or unaccompanied baggage). b. Balikbayan Box – a type of baggage containing items being sent by overseas Filipinos (known as “balikbayans”) usually for their relatives, friends, and colleagues after being away for a period of time. This may also be either accompanied or unaccompanied. c. Parcel – a package containing items or goods which are routed through the postal service (i.e. Philippine Postal Corporation [PhilPost]) or other courier service providers. d. Privilege – the benefit extended to a passenger (for baggage) or balikbayan (for balikbayan box) when applicable conditions are satisfied. e. Commercial Quantity – quantity of items or goods which are considered adequate for commerce. f. DFA – Department of Foreign Affairs, the national government agency which issues passport to Filipino citizens for their foreign travels. g. DOLE – Department of Labor and Employment, the national government agency in charge of the labor and employment policies, programs, and services. h. POEA – Philippine Overseas Employment Agency, the main government agency assigned to monitor and supervise recruitment agencies in the Philippines. i. OFW – Overseas Filipino Worker, a Filipino citizen who works on a foreign country with a passport duly issued by DFA and certified by DOLE or POEA. j. Returning Resident – a Filipino citizen who returns to the Philippines after being outside of the country for at least six (6) months. -

Eileen R. Tabios

POST BLING BLING By Eileen R. Tabios moria -- chicago -- 2005 copyright © 2005 Eileen R. Tabios ISBN: 1411647831 book design by William Allegrezza moria 1151 E. 56th St. #2 Chicago, IL 60637 http://www.moriapoetry.com CONTENTS Page I. POST BLING BLING 1 [Terse-et] 2 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID 3 Robert De Niro 4 Infinity Infiniti 5 FOR THE GREATER GOOD 6 THE BEACH IS SERVED 7 “Paloma’s Groove” 8 Be Yourself At Home 9 Your Choice. Your Chase. 10 ESCAPE: Built For The Road Ahead 11 Microsoft Couplet: A Poetics 12 THE DIAMOND TRADING COMPANY—JUST GLITTERING WITH FEMINISM!! 13 W Hotels 14 SWEETHEART 15 YUKON DENALI’S DENIAL II. A LONG DISTANCE LOVE 18 LETTERS FROM THE BALIKBAYAN BOX 40 NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I. POST BLING BLING In a global, capitalistic culture logotypes exist (Nike, McDonalds, Red Cross) which are recognizable by almost all of the planet´s inhabitants. Their meanings and connotations are familiar to more people than any other proper noun of any given language. This phenomenon has caused some artists to reflect on the semiotic content of the words they use, (for example, in the names of perfumes) and isolate them, stripping them down to their pure advertising content. Words are no longer associated with a product, package or price, and go back to their original meaning or to a new one created by the artist. —from Galeria Helga de Alvear's exhibition statement for “Ads, Logos and Videotapes” (Estudio Helga de Alvear), Nov 16 - Jan 13, 2001 [Terse-et] V A N I T Y F A I R V A N I T Y F A R V A N I T Y A I R 1 WELCOME TO THE LUXURY HYBRID It’s not just the debut of a new car, but of a new category. -

12 DO's and DONT's of Balikbayan-Box Shipping

12 DO's and DONT's of Balikbayan-box Shipping 12 DO's and DONT's of Balikbayan-box giving. Filipinos from all over the globe are already checking their list and (checking it twice) to make sure they get presents for each of their loved ones back home in the Philippines. But before you toss those goodies into a box you would send to family and friends across the Pacific, remember that sending the only-in-da-Philippines tradition of balikbayan-box giving is not as easy as sealing the box with package tape ten times over and calling a freight-forwarding company to pick it up at your house. Here are 12 things you need to look out for to ensure that the presents you bought out of your hard-earned money make it to the right people at the perfect time. 1. DO EVALUATE THE FREIGHT-FORWARDING COMPANY YOU WILL TRUST YOUR BOX WITH. Manny Paez, owner of Manila Forwarder, one of the leading balikbayan-box companies in the United States right now, advises his fellow kababayans to pay attention to the first phone call they would make to the company. Yes, right when you call – when you talk to them on the phone, when you talk to their staff. Apparently, this says a lot about the company. Most companies are hard to contact and when you finally get through, you will be talking to an answering machine. This will say something about the company, how ill-equipped they are, how they may not have enough personnel to take care of their client’s needs or provide the quality of service that clients deserve. -

The Filipino Century Beyond Hawaii

THE FILIPINO CENTURY BEYOND HAWAII International Conference on the Hawaii Filipino Centennial December 13 - 17. 2006 Honolulu. Hawaii CENTER FOR PHILIPPINE STUDIES School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA Copyright 2006 Published by Centerfor Philippine Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa Printed by PROFESSIONAL IMAGE 2633 S. King Street Honolulu, HI 96822 Phone: 973-6599 Fax: 973-6595 ABOUT THE COVERS Front: "Man with a Hat" - Filipino Centennial Celebration Commission Official Logo University ofHawaii System and University ofHawaii at Manoa Official Seal "Gold Maranao Sun" - Philippine Studies Official Logo by Corky Trinidad "Sakada Collage" - Artwork by Corky Trinidad Back: Laborer sInternational Union ofNorth America Local 368, AFL-CIO (Ad) ii L~ The Filipino Century Beyond Hawaii International Conference on the Hawaii Filipino Centennial Sponsors Filipino Centennial Celebration Commission (in partnership with First Hawaiian Bank) Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa Acknowledgments iii The Role That Filipinos Played in Co-sponsors Democratization in Hawaii Office of the Chancellor, UH Manoa By Justice Benjamin E. Menor 1 Office of Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Messages Education, UH Manoa Governor Linda Lingle 3 School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies Philippine Consul General (SHAPS), UH Manoa Ariel Abadilla 4 Group Builders, Inc. University ofHawaii President Pecson and Associates David McClain 5 UH Manoa Chancellor Conference Committee Denise Eby Konan 7 Belinda A. Aquino UH Manoa SHAPS Interim Dean ChairpersonlEditor Edward J. Shultz 8 Filipino Centennial Celebration Rose Cruz Churma Commission, Chairman Vice Chairperson Elias T. Beniga 9 Center for Philippine Studies, Federico V. -

The Filipino Nation in Daly City

1 A REPEATED TURNING ne will hear the joke told, eventually, though it hardly ever sounds like one. It’s almost always delivered casually, thrown out like an off- Ohand rhetorical question, as a matter of incontestable fact. “You know why it’s always foggy in Daly City, right? Because all the Filipinos turn on their rice cookers at the same time.” This par tic u lar teller of the joke (Wally, a news- paper photographer) and I (a student of anthropology) are sitting in scuffed plastic chairs in the living room of his cramped apartment in the Pinoy capital of the United States. We are both among the 33,000 Filipino residents of Daly City, California, where one out of three people are of Filipino descent. It is a freezing afternoon in late August, and we are looking through the damp glass of the window that faces out onto the quiet suburban street. Out- side the fog swirls, tugged by the wind into gentle twists of cotton, spilling over the roofs and parallel- parked Hondas. But inside, it is warm, as it does not take much time to heat up the small room cluttered with boxes of bulk food purchased from Costco, cassette tapes, photography books, and an open balikbayan box addressed to Wally’s parents in Quezon City. Wally, with a half- consumed bottle of beer in one hand, leans back in his chair after delivering the punch line, and waits for my reaction. I grin widely, because it is hard not to. I’ve always found it really funny. -

TRANSFORMATIONS Comparative Study of Social Transformations

TRANSFORMATIONS comparative study of social transformations CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor " 'Your Grief is Our Gossip0: Overseas Filipinos and Other Spectral Presencesn Vicente Rafael CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #I11 Paper #538 October 1996 Forthcoming in Public Culture, 1997. Vicente L. Rafael University of California at San Diego "Your Grief is Our Gossi~"~: Overseas Fili~inosand Other S~ectralPresences This essay grows out of an interest in nationalism as a kind of affect productive of a community of longing. My concern lies in the emergence of nationalist sentiment (as distinct from the institutionalization of nationalist ideology and its accompanying disciplinary technologies) in and through the work of mourning particular and exemplary deaths amid the collusion of the state. with transnational capital.' Focusing on recent events in the Philippines, particularly with regard to the increasing flows of immigrants and overseas contract workers, I inquire into nationalist attempts at containing the dislocating effects of global capital through the collective mourning for its victims. This labor of mourning, however, tends to bring forth the uncanny nature of capitalist development itself on which the nation-state depends. The moral economy of grieving is persistently haunted by the circulation of money. Hence, while nationalist mourning is borne by the desire of the living to defer to the dead, thereby giving rise to the sensation of each belonging to the other, it also anticipates its own failure amid the relentless commodification of everyday life. Often, the form which that anticipation takes, especially in a society saturated by commercially-driven mass media, is gossip. -

Lbc Price Rate for Documents

Lbc Price Rate For Documents whileCandent flatulent Poul Sigmundscavenge blackens some poniard her diabolist after chippy fully andZacharia foretokens Romanised distressingly. tetchily. Hartwell gutturalize pleonastically? Morganatic and talc Galen premonish Get rates documents easier, lbc documents such delays for solving my question is a document with a lot of full list approved and ship worldwide. Because the Group charges for sea freight forwarding based on standard dimensions of the box rather than weight, receipts, lbc international items will incorporate in sending money online sellers to think about your morning. It is like combining the advantages of each logistics company and select the one that fits my order the better. Glad to lbc for. LBC has terrific news for online sellers. Was for lbc rates to? Ensuring customers have the air travel information they need quickly and accurately is the cornerstone of a great travel service. Lbc in philippines set you can picked up their next number into sending from home? Keeps the tracking nos I searched and succeed can fill not rescue one and updates me leave now pain then. 1 reviews of LBC Sacramento Its affiliate first diamond to send LBC box lid though we. Luzon sta rosa laguna to pay for a document, such as long will cost much beauty products. It is important to know what window are to sequence any inconvenience. Join the 16 people own've already reviewed LBC Express. LBC PACKAGEDOCUMENTS SHIPPINGREMITTANCEINTERNATIONAL RATES Last update June 20 2017 Click on pictures to see larger version zoom-in. We began creating a good company also expanded its continuous service and payment, improve your boxes to imus to ship it is that you? Also placed inside the box is the photo they took of my item when it arrived in their warehouse. -

Chris Martin

London School of Economics and Political Science Generations of Migration: Schooling, Youth & Transnationalism in the Philippines Christopher A.T. Martin A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, December 2015 !1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,996 words. !2 Abstract The Philippines is one of the world’s largest ‘sending communities’ for international labour migrants, with roughly 10% of the population ‘absent’ due to emigrations associ- ated with permanent relocation or short-term contract work. Anthropologists studying Filipino migrations have often focussed on the migrants themselves, and particularly their experiences of diaspora and transnationalism in the present; this thesis instead looks at the perspectives of those who remain in the Philippines, particularly the children and young people who are affected by labour migration, and who often consider working overseas as part of their own futures. -

Helena Patzer UNPACKING the BALIKBAYAN BOX. LONG

STUDIA SOCJOLOGICZNE 2018, 4 (231) ISSN 0039−3371, e-ISSN 2545–2770 DOI: 10.24425/122486 Helena Patzer Institute of Ethnology, Czech Academy of Sciences UNPACKING THE BALIKBAYAN BOX. LONG-DISTANCE CARE THROUGH FEEDING AND FOOD CONSUMPTION IN THE PHILIPPINES This article explores caring through feeding as an important aspect of transnational family life, and analyzes the practices connected to sending food products home, supervising what the family eats, and changing consumption patterns. It focuses on Filipino migrants to the United States who maintain transnational ties with their families. With a history of colonial encounter, the United States has been a popular migration destination, and has also strongly infl uenced food consumption. The study shows the ways in which packages from abroad (balikbayan boxes) express love and care, and how they allow migrants to control food consumption of the family in the country of origin. By looking at the goods the immigrants put in the packages, and the way these are received, it is possible to uncover the dynamics of love, care, and intimacy in transnational families, which often translate into power, tensions, and control among family-members. The article analyses how food products sent in the packages work, bringing with them new ideas and practices, creating imaginaries of migration, and building the social prestige of the immigrant. Using the concept of “social remittances”, the article also shows the changing patterns of food consumption in the Philippines. Keywords: migration, food parcels, care, consumption patterns, Philippines Rozpakowując balikbayan box. Troska na odległość poprzez karmienie oraz konsumpcja jedzenia na Filipinach Streszczenie Artykuł opisuje troskę na odległość poprzez karmienie jako ważny aspekt transnaro- dowego życia rodzinnego, a także analizuje praktykę wysyłania jedzenia do kraju pocho- dzenia, nadzór nad tym, co je rodzina, i jak zmieniają się wzorce konsumpcji. -

Filipinos Depicted in American Culture Eileen Regullano

e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work Volume 3 Article 6 Number 1 Vol 3, No 1 (2012) September 2014 Filipinos Depicted in American Culture Eileen Regullano Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/e-Research Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Regullano, Eileen (2014) "Filipinos Depicted in American Culture," e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/e-Research/vol3/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regullano: Filipinos Depicted in American Culture Filipinos Depicted in American Culture e-Research: A Journal of Undergraduate Work, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Regullano Filipinos Depicted in American Culture Eileen Regullano Abstract: From the early 20th century, Filipinos have been depicted as treacherous savages or as innocent children in America, evidenced in political comics and comments from the time. In today's society, even though the depictions are not as blatantly racist as they were in the early 20th century, Filipinos are dehumanized, exoticized, or idealized and represented in a two-dimensional way. However, this construction of the Filipino identity may be starting to change with the advent of more ardent vocalization by Filipinos with regard to the production of their images. -

University of California Santa Cruz Filipino Poethics

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ FILIPINO POETHICS: READING THE PHILIPPINES BEYOND THE OBJECT/SUBJECT DIVIDE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Fritzie Mae A. de Mata September 2017 The Dissertation of Fritzie Mae A. de Mata is approved: _________________________________ Professor Wlad Godzich, Chair _________________________________ Professor Christopher Connery _________________________________ Professor James Clifford _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Fritzie Mae A. de Mata 2017 ! ! Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1-15 Chapter One Institutionalizing Tagalog: Odulio’s Tagalog Translation of Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere 16-67 Chapter Two The Institutionalization of Asian American Studies: Setting Boundaries of Inclusion and Exclusion in the U.S. Academy 68-109 Chapter Three Zeugmatic Formations: Balikbayan Boxes and the Filipino Diaspora 110-147 Chapter Four Beyond Representation: Reading Jessica Hagedorn’s Dogeaters 148-214 Coda 215-222 Bibliography 223-230 ! iii Abstract Fritzie Mae A. de Mata Filipino Poethics: Reading the Philippines Beyond the Object/Subject Divide My dissertation posits the necessity of formulating a new way of reading literary texts and other cultural production beyond the frameworks of identity, nationalism, and nation-state. Philippine Studies and Asian American Studies have been traditionally understood through representations of ethnic and national identities. However, approaches to knowledge based on identity limit our understanding of experience because they erase the singularity of each individual’s experiences. For instance, my work demonstrates how the Tagalog translation of Jose Rizal’s Spanish novel, Noli Me Tangere, enables the production of a unified imagining of a Philippine nation and Filipino identity despite the Philippines’ complex array of heterogeneous linguistic and cultural identifications.