A Working Class Hero Is Something to Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Various Absolute Dansband Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Absolute Dansband mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Absolute Dansband Country: Sweden Released: 2007 Style: Schlager MP3 version RAR size: 1745 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1889 mb WMA version RAR size: 1321 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 108 Other Formats: DXD WAV MMF MPC VOC DMF VOC Tracklist 1-1 –Streaplers Till Min Kära 1-2 –Lasse Stefanz Du Försvann Som En Vind 1-3 –Thorleifs Och Du Tände Stjärnorna 1-4 –Black Jack* Inget Kan Stoppa Oss Nu 1-5 –Vikingarna Den Stora Dagen 1-6 –Matz Bladhs Tusen Bitar 1-7 –Berth Idoffs Små Små Ord Av Kärlek 1-8 –Lennartz Leende Guldbruna Ögon 1-9 –Torgny Melins* Nu Är Det Lördag Igen 1-10 –Barbados Rosalita 1-11 –Mathias Holmgren Något Som Kan Hända 1-12 –Arvingarna Det Ensammas Promenad 1-13 –Shanes Vem Får Följa Dig Hem 1-14 –Stefan Borsch Ännu Doftar Kärlek 1-15 –Candela Viva Fernando Garcia 1-16 –Schytts En Spännande Dag För Josefine 1-17 –Thorleifs En Liten Ängel 1-18 –Tommys Vår Dotter 1-19 –Hans Martin Där Rosor Aldrig Dör 1-20 –Curt Haagers Tio Tusen Röda Rosor 1-21 –Ingmar Nordströms Gabriellas Sång 2-1 –Thorleifs Med Dig Vill Jag Leva 2-2 –Sven-Ingvars Två Mörka Ögon 2-3 –Matz Bladhs Vid Silverforsens Strand 2-4 –Stefan Borsch Vid En Liten Fiskehamn 2-5 –Lasse Stefanz Tårar Från Himlen 2-6 –Flamingokvintetten & Allstars Gamla Goa Gäng 2-7 –Mats Bergmans Kan Du Hålla Dom Orden 2-8 –Fernandoz & Git Persson Nej Så Tjock Du Har Blitt 2-9 –Kellys Ett Litet Ljus 2-10 –Göran Lindberg* Den Röda Stugan 2-11 –Wizex Mjölnarens Irene 2-12 –Joy Ride* God Morgon Världen 2-13 –Grönvalls* -

C:\Users\Anders Berglund\Docume

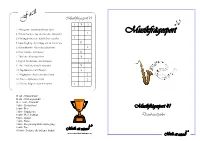

acit F Musikfrågesport 41 1 x 2 1. Vikingarna - Leende guldbruna ögon 1 2. Sten & Stanley - Jag vill vara din, Margareta 2 Musikfrågesport 3. Flamingokvintetten - Kärleksbrev i sanden 1 4. Lotta Engberg - Fyra Bugg och en Coca Cola x 5. Stefan Borsch - Vid en liten fiskehamn 2 6. Cool Candys - Göta kanal x 7. Thorleifs - Gråt inga tårar x 8. Ingmar Nordströms - Gösta Gigolo. 2 9. 1957 - Man ska leva för varandra x 10. Fågeldansen - Curt Haagers x 11. Magnusson - Någon att hålla i hand 2 12. Wisex - Mjölnarens Irene 2 13. Christer Sjögren - Ljus och värme 1 13 rätt - Mästarklass! 12 rätt - Nästan perfekt! 10 - 11 rätt - Utmärkt! 9 rätt - Mycket bra! 8 rätt - Bra! Musikfrågesport 41 7 rätt - Ganska bra 6 rätt - Medelmåttigt Dansbandspärlor 5 rätt - Hyfsat 4 rätt - Sådär... 3 rätt - Det går nog bättre nästa gång... 2 rätt - Tja... 0-1 rätt - Ni har i alla fall inte fuskat! www.musikattminnas.se Musikfrågesport 41 9. Så till en verklig klassiker: Man ska leva för varandra. Spelar och sjunger gör förstås Trio med Bumba. Bandet bildades på Söder i Stockholm, vilket år skedde det? Dansbandspärlor 11947 x1957 21967 10. Som tionde melodi spelar Curt Haagers en instrumental låt som gissningsvis ganska många känner igen. Vad heter den? 1 Oxdansen x Fågeldansen 2 Ballongdansen 1. Nu får väl alla som är blåögda försöka att stålsätta sig! Vi inleder nämligen dansen med Leende guldbruna ögon. Vad heter bandet som spelar upp till dans? 11. Någon vän att hålla i hand, det stämmer nog att det vill de flesta av oss ha. -

It's Hard to Be a Cowboy So Far from the West

It's Hard to Be a Cowboy So Far from the West Trender i sångtexternas språkval, tematik och författarskap i Mats Rådbergs och Rankarnas skivutgivning 1969–2002 Anders N. Nilsson Litteraturvetenskap C, 30 högskolepoäng Uppsats 15 högskolepoäng Ht 2008 Handledare: Anders Pettersson Anders N. Nilsson: Trender i Mats Rådbergs och Rankarnas skivutgivning 1969-2002 Innehållsförteckning Inledning ........................................................................................................ 4 Amerikansk och svensk countrymusik .......................................................... 5 Originalet ................................................................................................. 5 Svenska former ......................................................................................... 5 Mats Rådberg & Rankarna ...................................................................... 7 Sångtexter som litteratur................................................................................ 9 Material och metod ...................................................................................... 11 Genomgång av album .................................................................................. 13 Gruppens album ..................................................................................... 13 Soloalbum............................................................................................... 18 Trender i språk och författarskap................................................................. 20 Tematik ....................................................................................................... -

XARC Mastering Mastered Projects 286 Rock EP CD USA Rock Album

XARC Mastering Mastered Projects 286 Profiled Independent Rock EP CD USA 2 Eyes 1 World Raw Virtual Records Inc Rock Album CD USA 2 Much 2 Much TBA Pop / Rock Single CD Canada 3:SLAX Sad Love Independent Progressive House Single CD USA 4Gotten Rolling Craftsman Records Rock EP CD Thailand 7fan Sur la plage... www.7fan.com House / Electro Single CD / Internet France 7fan Booby-Trap www.7fan.com Electro / Trance / Tek-House Single CD / Internet France 7Fan and Mae These Seconds www.7fan.com House / Electro Single CD / Internet France 9-Fifty Heads Up / Face Down 60062 Records Alterna-Pop Album CD USA A Black Market Diary Tight on two TBA Rock / Hardcore Song CD / Internet USA a.m.aroma Doubts / I can almost hear them planning my destruction Sumu Records Downtempo Single CD Finland A.M.S. Equillibrium AMS Records Trance Single CD UK Adele Russotto Battito Intenso Maxsound Records R & B / Pop Single CD / Internet Italy Adrien Szekeres Engedd hát ... Emi Hungary / Private Moon Music Pop Single CD Hungary Advent Family Singers Bulowa TBA Religious Album CD Zambia Affusion Dare To Go Deep BeatSquad Productions Gospel / Soul For Album release CD / Internet USA Afroorganic Sum Prof Productions Afro Organic House Single CD / Vinyl UK Ahmed Saleh Musical Moments ALIEN Records Classical Piano Album CD / MC Kuwait Aladin Sani Denominator Independent Hip Hop Single CD Austria Alan Lauris Connect me Independent Pop Album CD / Internet The Netherlands Alan Lauris Dutch cities Canal Island Records Pop Single CD / Internet The Netherlands Alan Lauris Different Frequency Canal Island Records Electrosingersongwriterpop Album CD / Internet The Netherlands Alan Pizzut Nu Funk Independent Electronic Single CD Italy Alan Pizzut Tibet Independent Electronic Single CD Italy Aldus B I, You, Me Independent Psy Trance Song - USA Aldus B. -

Ladda Ner Som PDF-Fil

VÅR OCH TM SOMMAR 2019 120SIDOR NÖJE Vi erbjuder bara bra och fantastiska nöjen HITTAR DU EN BÄTTRE NÖJESFÖRMEDLING - RING DEM! Levereras med en integrerad 3-kanalig mixer med reverb och Bluetooth-streaming. Du får snabbt ett utmärkt ljud med ToneMatch-behandling för mikrofoner och akustisk gitarr, medan du spelar upp musik trådlöst från din mobila enhet. Välkommen till Nöjestorget Sveriges största nöjesförmedling hälsar våren och sommaren väl- kommen och ser fram emot mycket underhållning i alla dess former. Med våra 25 år av nöjesbokning har vi stora utbud vi kan erbjuda. En utgåva nu samlat våra krafter och tar nya steg som vi hoppas kan vara vägledande och i utvecklingen för att kunna erbjuda inspirerande för framtida event och ännu bättre service, fler möjligheter engagemang. och nya sätt att sprida våra nöjen. Vem kunde tro att det skulle vara både Personligen tycker jag att mitt jobb är kul och utvecklande att jobba med det bästa i världen och hoppas att våra underhållning i alla dess former? tjänster är väl uppskattade. Väl mött och mkt nöje, Denna katalog, i samarbete med deltagande nöjesleverantörer, presenterar några av alla våra artister Ulf Bejerstrand Bejerstrand www.bose.se och nöjen som väl understryker det och alla andra på Nöjestorget ARTISTER OCH NÖJEN I BOKSTAVSORDNING 6 Alain Autio Jazz, Blues 36 Elin Örebrand Bar- och loungepianist 66 Mike Trolleri, Konferencier 96 Som’ thin’ Jazz 7 Allan & Mange Pop, 50-tal, 60-tal 37 Emily Winter Country, Folkrock 67 Mona Rosell Klassiskt 97 Soul Pack Coverband, Soul 8 Alpen Kapelle -

Årets Hederspris Per Gessle K Rosmar Innehåll E Arolin

Musikför läggarnas pris2010 Årets hederspris Per Gessle k rosmar innehåll e arolin Årets hederspris: per Gessle 3 : c Årets kompositör 6 foto Årets textförfattare 7 Årets konstmusik – stor ensemble/opera 8 Årets konstmusik Välkommen till Sveriges – kammarmusik 9 Årets internationella framgång 10 roligaste musikprisgala! Årets nykomling 11 å ska vi ännu en gång fira och och glada över att ha Per som hedersgäst dela ut priser till våra fantastiska på årets gala. Årets låt 12 låtskrivare som år från år sätter Vi hoppas att ni alla får en fantastisk D Sverige på kartan som ett av de ledande dag och kväll med god mat och dryck, tema: hårdrock - dansband 13 musikländerna i världen, framförallt när många skratt, spänning och suverän det gäller upphovsmän och kompositörer. musik. Skål och varmt välkomna till Vi fortsätter det som många ansett vara Musikförläggarnas Pris 2010! Årets projektledare Sveriges roligaste musikprisgala genom att Karin Larsdotter pris återigen vara på Berns och starta mitt på heders dagen för att avrunda någon gång runt skribenter Ola håkansson Karin Larsdotter midnatt. Även i år är Anders Lundquist konferencier, nu för tredje året i rad. Ola Kjell-Åke hamrén har aviserat att detta blir hans sista så vi Martin Ingeström, david Mortimer-hawkins har redan nu börjat arbetet med vem som Festgeneral thomas deutgen leder galan nästa år. Vi fortsätter också satsningen på att belysa en del upphovs- Omslagsfoto män som kanske inte så ofta vinner priser Caroline rosmark på en sådan här gala, men som betyder mycket för svensk musikindustri. Förra Ansvarig utgivare Han har Nutta hultman året uppmärksammade vi bland annat Swedish House Mafia och framgångarna Grafisk form för svenska låtskrivare i Asien. -

Fakta Om Fredagens Konsert

FAKTA OM FREDAGENS KONSERT Ni är alla hjärtligt välkomna till fredagens konsert på Malmö Youth Games. Konserten börjar kl:19.00 och slutar kl:23.30. Insläppet öppnar kl:17.30. Fredagens artister är följande: Kl:19.00 Elderidge Kl:20.00 Charlotte Perelli Kl:21.00 The Poodles Kl:22.30 EMD Nedan följer en presentation av artisterna: Elderidge Elderidge bildades i slutet av nittiotalet av bröderna Niclas och Tobias Granström och har alltsedan dess varit kärnan i gruppen. Från trevande ungdomsår i olika konstellationer har man nu hittat en framgångsrik form som sedan 2006 varit konstant med en klassisk sättning med gitarr, bas, trummor och sång. Naturligtvis tar man stor hjälp av den elektronik som dagens moderna studios erbjuder. Musiken beskrivs som russinen ur den kaka som Coldplay, Kent, Muse, Mew, Radiohead, Midlake, Kashmir, Ed Harcourt, Sigur rós, The killers m.fl har gett oss under åren. Produktionen som är både intim och svulstig på samma gång och förläggs nästan uteslutande i den studio som skämtsamt går under namnet "Bordellen" och som ligger oförskämt centralt på Götgatan i Stockholm. En EP som har namnet Abandoned Dreams nådde både skivdiskar och lyssnare den femte maj 2008. Detta firades förstås med ett stort kalas på Klubben, Fryshuset i Hammarby Sjöstad. Sommaren är sedan vigd åt att förmedla musiken till den levande publiken ute i landet. Det börjar röra på sig... Gruppen idag består av: Tobias Granström (Vocals & Guitars) Niclas Granström (Bass) och Erik "Erik-Boy" Nordstrand (Drums) Charlotte Perelli Född: 1974-10-07 Familj: Maken Nicola Perrelli och sönerna Angelo och Alessio. -

Det Kommer Från Hjärtat” - Dansbandsbranschens Förmåga Att Anpassa Sina Strategier Efter Förändrade Omvärldsfaktorer

”Det kommer från hjärtat” - Dansbandsbranschens förmåga att anpassa sina strategier efter förändrade omvärldsfaktorer Författare: Malin Hesselryd David Söderman Handledare: Thomas Karlsson Ämne: Företagsekonomi Nivå och termin: C-nivå, HT 2009 Handelshögskolan BBS Innehållsförteckning 1 INLEDNING ............................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 BAKGRUND ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 PROBLEMFORMULERING ...................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 FORSKNINGSFRÅGOR ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 SYFTE ................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.5 MÅLGRUPP .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.6 BEGREPPSDEFINITION .......................................................................................................................... 8 1.7 UPPSATSENS FORTSATTA DISPOSITION .................................................................................................. 8 2 METOD ................................................................................................................................................... -

Gagen, Justin. 2019. Hybrids and Fragments: Music, Genre, Culture and Technology

Gagen, Justin. 2019. Hybrids and Fragments: Music, Genre, Culture and Technology. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/28228/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] Hybrids and Fragments Music, Genre, Culture and Technology Author Supervisor Justin Mark GAGEN Dr. Christophe RHODES Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science GOLDSMITHS,UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTING November 18, 2019 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Justin Mark Gagen, declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is clearly stated. Signed: Date: November 18, 2019 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr. Christophe Rhodes and Dr. Dhiraj Murthy. You have both been invaluable! Thanks are due to Prof. Tim Crawford for initiating the Transforming Musicology project, and providing advice at regular intervals. To my Transforming Musicology compatriots, Richard, David, Ben, Gabin, Daniel, Alan, Laurence, Mark, Kevin, Terhi, Carolin, Geraint, Nick, Ken and Frans: my thanks for all of the useful feedback and advice over the course of the project. -

Steinar Karaoke

2 Become 1 Spice girls Six 1 1 2 Princes Spin Doctors Laserdisc-15-31 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Laserdisc-13-24 500 miles Various Artists Laserdisc-02-75 500 miles away from home Bobby Bare GREMIX1 6 634-5789 Blues Brothers EK-BB01 10 74-75 The Conells Laserdisc-15-60 800 grader Svenska Hits 2 Laserdisc-18-93 A boy from nowhere Tom Jones EK01 6 A boy named Sue Johnny Cash EK14 4 A change will do you good Sheryl Crow Laserdisc-16-44 A design for life Manic Street Preachers Laserdisc-16-34 A fool such as I Elvis Presley Laserdisc-11-53 A Gordon for me Various Laserdisc-12-88 A groovy kind of love Phil Collins Laserdisc-11-61 A groovy kind of love Phil Collins Laserdisc-12-47 A Hard Days Night Beatles Laserdisc-19-05 A hard day's night Beatles Laserdisc-03-07 A horse with no name America Laserdisc-06-92 A hundred pounds of clay Gene McDaniels Laserdisc-07-70 A little bitty tear Burl Ives EK14 15 A million love songs Take That Six 3 9 A rainy night in Georgia Brook Benton 40A5 A song for the lovers Richard Ashcroft ET30 6 A teenager in love Dion & The Belmonts EK13 10 A white sport coat Marty Robbins Laserdisc-05-49 A whiter shade of pale Procol Harum EK26 12 A World Without love Peter & Gordon Laserdisc-19-58 Abba medley Stars on 45 GREMIX1 15 Abbey road medley Beatles GREMIX1 7 Achey Breaky Heart Cyrus, Billy Ray Six 3 8 Addicted to love Robert Palmer Laserdisc-01-43 Addicted to love Robert Palmer EK07 4 Ae fond kiss Peter Morrison Laserdisc-13-75 Africa Toto PKL28 B14 After all (Love theme from Chances are) Cher with Peter Cetera Laserdisk-08-13 -

Semantic Annotation of Music Collections: a Computational Approach

Semantic Annotation of Music Collections: A Computational Approach Mohamed Sordo TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2011 Directors de la tesi: Dr. Xavier Serra i Casals Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Dr. Òscar Celma i Herrada Gracenote, Emeryville, CA, USA Copyright c Mohamed Sordo, 2011. Dissertation submitted to the Department of Information and Communication Technologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the require- ments for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA, with the mention of European Doctor. Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Dept. of Information and Communica- tion Technologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www. upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. A Radia, Idris y Randa. Me siento muy orgulloso de ser vuestro hijo y tu hermano. A toda mi familia. Acknowledgements During these last few years, I had the luck to work with an amazing group of people at the Music Technology Group. First and foremost, I would specially like to thank 3 people regarding this dissertation. Xavier Serra, for giving me the opportunity to join the Music Technology Group, and for his wise advices in key moments of the thesis work. Òscar Celma, for being the perfect co- supervisor a post–graduate student can have. Whether it was for guidance or for publishing, he was always there. Fabien Gouyon, who would have been without any doubt the third supervisor of this thesis. I especially thank him for giving me the opportunity to join his research group in the wonderful city of Porto, as a research stay. -

Folk & Världsmusikgalan 2014

NORRLANDSOPERAN OCH FOLKETS HUS 19–23 FEBRUARI & UMEFOLK 2014 KONSERTER DANS MÄSSA SEMINARIER SPEL WORKSHOPS VARMT VÄLKOMMEN TILL UMEÅ GALAN DIREKTSÄNDS I SVERIGES RADIO P2 SAMT PÅ FOLKGALAN.SE Umeå är i år Kulturhuvudstad i Europa. Vårt perspektiv på året är lokalt och regionalt. Hur kan vi berika Sverige och Norrland med kultur utifrån och vad är vårt bidrag från kulturlivet i norr till Sverige, Europa och världen? Självklart har folk- och världsmusik en viktig roll när vi ser på oss utifrån och stolt vill främja det som är unikt här. När folkmusikvågen drog över Sverige på 1970-talet var föreningen Gnid & Drag i Umeå en av drivkrafterna. Ur Gnid & Drag föddes folkmusikfestivalen som i år berikas av och berikar den femte Folk & Världsmusikgalan. Det är första gången som galan kombineras med en festival. Umefolk har genom buskspel och jam, genom dans till folkmusiken och ett engagemang för att välkomna nya till genren, inte minst mängder av barn och unga från kulturskolorna, tagit fasta på sitt 70-talsarv samtidigt som den odlar genrens professio- nella utveckling och bjuder på mycket nytt och oväntat. Galan i Umeå har valt sina teman utifrån ett Norrlands- och Europaperspektiv. Det blir möjligheter att på seminarier fördjupa sig i berättande och folkmusik, minoriteter i norr, jämställdhet – med premiär för ett speciellt gala- och festi- valprojekt – samt Europa. Bonusteman på initiativ från galans partners kommer att handla om visgenren, dans, mångfald, arrangörer och mycket annat. Vi ser fram emot en gala, festi- val, seminarier, mässa som samlar folk- och världsmusikgen- ren i Sverige kryddad med gäster från Norden och Europa.