Petition for Review ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NASSAU GUN LIST 1 Walther P22 22 Pistol Semi Auto New In

NASSAU GUN LIST 1 Walther P22 22 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box - Two Tone Nickel 2 Beretta PX4 Storm 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 3 Ruger LCR 38 Pistol Revolver New in Box 4 SCCY CPX-3 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 5 Taurus 709 Slim 9mm Pistol Semi Auto USED - No box 6 Taurus PT24/7 40 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 7 Taurus Judge 45 / 410 Pistol Semi Auto USED - No box 8 Charter Bulldog 44 Pistol Revolver New in Box 9 FN FNX 9mm Pistol Semi Auto USED Two Tone 10 Keltec P11 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 11 Walther PK380 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box - 2 Tone 12 Astra Astra Police 38 Pistol Revolver New in Box 13 S&W 638-3 38 Pistol Revolver New in Box 14 Bersa BP380CC 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 15 FN FNS 40 Pistol Semi Auto USED 16 I.O. Inc. Hellcat 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 17 Ruger American Compact 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 18 Ruger Security 9 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 19 S&W M&P C 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box - Safety Model 20 Sig Sauer P290 9mm Pistol Semi Auto USED - Two Tone with 2 mags 21 Mossberg 500 12g Shotgun Pump Combo, 28" barrel and 18" barrel 22 Western Field M550A 12g Shotgun Pump New/No Box 23 Huglu 12g Shotgun SXS New/No Box Folding Single Barrel New/No Box 24 H&R 12g Shotgun 25 Henry Acubolt 22MAG Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 26 Marlin XT-22MR 22 WMR Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 27 Remington 700 30-06 Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 28 Remington 783 270 Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 29 Savage 11F 308 WIN Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 30 Henry Golden Boy 17HMR Rifle Lever Action New in Box 31 -

Nassau Gun List 1 Walther P22 22 Pistol Semi Auto 2 Beretta PX4

Nassau Gun List 1 Walther P22 22 Pistol Semi Auto 2 Beretta PX4 Storm 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 3 Ruger LCR 38 Pistol Revolver 4 SCCY CPX-3 380 Pistol Semi Auto 5 Taurus 709 Slim 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 6 Taurus PT247 40 Pistol Semi Auto 7 Taurus Judge 45 Pistol Semi Auto 8 Charter Bulldog 44 Pistol Revolver 9 FN FNX 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 10 Keltec P11 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 11 Walther PK380 380 Pistol Semi Auto 12 Astra Astra Police 38 Pistol Revolver 13 S&W 638-3 38 Pistol Revolver 14 Bersa BP380CC 380 Pistol Semi Auto 15 FN FNS 40 Pistol Semi Auto 16 I.O. Inc. Hellcat 380 Pistol Semi Auto 17 Ruger American 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 18 Ruger Security 9 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 19 S&W M&P C 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 20 Sig Sauer P290 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 21 Mossberg 500 12g Shotgun Pump 22 Western Field M550A 12g Shotgun Pump 23 Huglu 12g Shotgun SXS 24 H&R Folding 12g Single Barrel Shotgun 25 Henry Acubolt 22MAG Rifle Bolt Action 26 Marlin XT-22MR 22 WMR Rifle Bolt Action 27 Remington 700 30-06 Rifle Bolt Action 28 Remington 783 270 Rifle Bolt Action 29 Savage 11FNS 301WIN Rifle Bolt Action 30 Henry Golden Boy 17HMR Rifle Lever Action Nassau Gun List 31 Marlin 60 22LR Rifle Semi Auto 32 Mossberg 715T 22 Rifle Semi Auto 33 Glock 22 40 Pistol Semi Auto 34 Honor Defense Honor Guard 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 35 Kahr Arms CW45 45 Pistol Semi Auto 36 Ruger American 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 37 Clarke 1st 32 Pistol Revolver 38 Bond Arms Brown Bear 45 colt Pistol Derringer 39 S&W 37 38 Pistol Revolver 40 S&W 642-1 38 Pistol Revolver 41 CZ P-09 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 42 Diamondback -

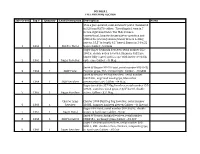

Sale Order Tag # Quantity Lead Description Description Caliber 1

Sale Order Tag # Quantity Lead Description Description Caliber Kel-Tec PLR-16 Pistol, serial number P2L64, The PLR-16 is a gas operated, semi-automatic pistol chambered in 5.56 mm NATO caliber. The rifling is 1 turn in 7 inches, right hand twist. The PLR- 16 has a conventional, long-stroke gas-piston operation and utilizes the proven Johnson/Stoner breech locking system. 18.5" in length, 9.2" barrel, Simmons 2-6 x 32 1 1361 1 Kel-Tec Pistol Scope. 5.56MM Ruger Super Redhawk Revolver, serial number 552-26919, double action revovler, Simmons 4x32 pro hunter fully coated optics scope 2 1362 1 Ruger Revolver with butler creek flip optic caps 44 Mag Smith & Wesson MP40 Pistol, serial number MPJ4948, Polymer 3 1363 1 S&W Pistol grips, TRL-1 Streamlight .40S&W Smith & Wesson 44 Mag Revolver, serial number M427490, engraved wood grips, blue velvet 4 1364 1 S&W Revolver presentation case 44 Mag Ruger Speed Six 357 Mag Revolver, serial number 157-60920, stainless, wood grips, 2 3/4" barrel, 5 1365 1 Ruger Revolver double action 357 Mag Charter 2000 Bull Dog Pug Charter Arms Revolver, serial number 13685, 6 1366 1 Revolver hammer has been altered 44 Special Ruger P89 Pistol, serial number 309-36595, double action, in hard 7 1367 1 Ruger Pistol case 9 MM Smith & Wesson Airlight Revolver, serial number CHR5654, pachmayr 8 1368 1 S&W Revolver grips .45 ACP Ruger Colt Redhawk Revolver, serial number 503-58514, BBL double action, stainless, composite 9 1369 1 Ruger Revolver grips, in hard case 45 Colt Taurus M905 Revolver, serial number DP25756, double -

UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the TENTH CIRCUIT COLORADO OUTFITTERS ASSOCIATION, Et Al., V. Plaintiffs- Appellants, No

Appellate Case: 14-1290 Document: 01019447389 Date Filed: 06/19/2015 Page: 1 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT COLORADO OUTFITTERS ASSOCIATION, et al., Plaintiffs- Appellants, No. 14-1290 v. JOHN W. HICKENLOOPER, Governor of the State of Colorado, Defendant-Appellee, JIM BEICKER, Sheriff of Fremont County, et al., Plaintiffs- Appellants, No. 14-1292 v. JOHN W. HICKENLOOPER, Governor of the State of Colorado, Defendant-Appellee. GOVERNOR’S MOTION TO STRIKE APPENDICES AND ASSOCIATED ARGUMENTS IN REPLY BRIEFS Appellate Case: 14-1290 Document: 01019447389 Date Filed: 06/19/2015 Page: 2 Defendant-Appellee John W. Hickenlooper, in his official capacity as Governor of the State of Colorado, hereby moves to strike Exhibit 1 to the appellee’s reply brief in Case No. 14-1290 (“FFLs’ reply brief”), and the Appendix attached to the appellee’s reply brief in Case No. 14- 1292 (“Sheriffs’ reply brief”), as well as the portions of the reply briefs that rely upon those documents. As grounds for this motion, Defendant states as follows: 1. Conferral pursuant to 10th Cir. R. 27.3. On June 11, 2015, undersigned counsel conferred with Peter Krumholz, counsel for Plaintiffs in Case No. 14-1290. Mr. Krumholz indicated that he was authorized to speak for Plaintiffs in both appeals, and that all Plaintiffs oppose this motion. 2. Both the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure and the Tenth Circuit’s local rules provide for the preparation and transmission of appendices containing the relevant portions of the record created in the district court. FRAP 30(a)(1); 10th Cir. -

Walther® Introduces New P22 Pistol with Integrated Laser Popular Rimfire Pistol Offers Improved Ergonomics and an Integrated Laser Sighting Device

STRATEGIC ALLIANCE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Industry Contact: Matt Rice Blue Heron Communications (800) 654-3766 [email protected] Walther® Introduces New P22 Pistol with Integrated Laser Popular Rimfire Pistol Offers Improved Ergonomics and an Integrated Laser Sighting Device SPRINGFIELD, Mass. (January 17, 2012) – Smith & Wesson Corp. the exclusive United States distributor of Walther® products, today announced a new version of the popular P22 pistol with an integrated laser sight. Combining reliable performance with an advanced sighting device, the new P22 is designed especially for shooters seeking a versatile, well-rounded .22 LR pistol. Featuring a uniquely designed laser sight built into the pistol frame, the new Walther P22 allows for rapid target acquisition with the simple press of a button. Compact, durable and seamlessly integrated to fit in front of the trigger guard, the new laser design will benefit Walther® P22 with Integrated Laser shooters of all experience levels. The integrated laser is fully adjustable for both windage and elevation and features a one-and-one- half hour run time of continuous operation. Battery replacement is made easy by simply unscrewing the battery cover. The class 3A laser offers a sight-in range of up to 25 meters and provides shooters with a 7mm focal point at 10 meters and a 15mm focal point at its furthest distance. The integrated laser is designed to handle a wide range of temperature settings, allowing users to deploy the laser device regardless of weather conditions. To activate the laser on the new P22, Walther has added a simple two-setting push button that enables the laser device to be easily turned on and off. -

Sale Order Tag # Quantity Lead Description Description Notes 1

OCTOBER 1 FALL FIREARMS AUCTION Sale Order Tag # Quantity Lead Description Kel-TecDescription PLR-16 Pistol, serial number P2L64, The PLR- Notes 16 is a gas operated, semi-automatic pistol chambered in 5.56 mm NATO caliber. The rifling is 1 turn in 7 inches, right hand twist. The PLR-16 has a conventional, long-stroke gas-piston operation and utilizes the proven Johnson/Stoner breech locking system. 18.5" in length, 9.2" barrel, Simmons 2-6 x 32 1 1361 1 Kel-Tec Pistol Scope. Caliber - 5.56mm Ruger Super Redhawk Revolver, serial number 552- 26919, double action revovler, Simmons 4x32 pro hunter fully coated optics scope with butler creek flip 2 1362 1 Ruger Revolver optic caps. Caliber - 44 Mag. Smith & Wesson MP40 Pistol, serial number MPJ4948, 3 1363 1 S&W Pistol Polymer grips, TRL-1 Streamlight Caliber - .40 S&W Smith & Wesson 44 Mag Revolver, serial number M427490, engraved wood grips, blue velvet 4 1364 1 S&W Revolver presentation case. Caliber - 44 Mag. Ruger Speed Six 357 Mag Revolver, serial number 157- 60920, stainless, wood grips, 2 3/4" barrel, double 5 1365 1 Ruger Revolver action. Caliber - 357 Mag. Charter Arms Charter 2000 Bull Dog Pug Revolver, serial number 6 1366 1 Revolver 13685, hammer has been altered. Caliber - 44 Special Ruger P89 Pistol, serial number 309-36595, double 7 1367 1 Ruger Pistol action, in hard case. Caliber - 9 mm Smith & Wesson Airlight Revolver, serial number 8 1368 1 S&W Revolver CHR5654, pachmayr grips. Caliber - .45 ACP Ruger Colt Redhawk Revolver, serial number 503- 58514, BBL double action, stainless, composite grips, 9 1369 1 Ruger Revolver in hard case. -

The Woman's Issue Returns!

INDUSTRY COMPANIES EMPOWERING DOMESTIC GET THE “NEW WAVE” 10 TAKE ON COVID-19 36 VIOLENCE SURVIVORS 54 PLUGGED IN TO YOUR STORE ® THE INDUSTRY’S BUSINESS MAGAZINE — EST. 1955 MAY 2020 THE WOMAN’S ISSUE RETURNS! MAKE IT SAFE, EVERY DAY The new SABRE Pepper Spray Launcher Home Defense Kit, from the #1 pepper spray brand trusted by law enforcement around the world, provides a home security and personal safety solution designed to deter a home intruder by creating an even greater distance between your customers and the threat. INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Easy, proven, and effective. Strategies In Times Of Panic Buying www.sabrered.com www.shootingindustry.com Section1_May-20.indd 1 4/16/20 3:36 PM NEW PRODUCTS FROM RUGER ARE YOU READY FOR TM OUR DEDICATED EMPLOYEES ARE ALWAYS WORKING THEIR HARDEST TO BRING YOU THE HIGH-QUALITY, AMERICAN-MADE FIREARMS YOU HAVE COME TO EXPECT FROM RUGER. FIREARM COATINGS? PC CHARGER™ The new PC Charger™ is a 9mm pistol based on our popular PC Carbine™ ArmorLube next-generation Chassis model. The PC Charger™ boasts an abundance of features including a 6.5'' barrel; an integrated rear Picatinny rail that allows PECVD DLC coatings deliver: for mounting of Picatinny-style braces; a glass-filled polymer chassis system; a flared magazine well for improved magazine reloading capabilities; and an ergonomic pistol grip with extended trigger reach. IMPROVED PRODUCT BENEFITS • Improved cycling rates ™ ® • Increased Reliability LITE RACK LCP II • Reduced Maintenance The new Lite Rack™ LCP® II is a • Greater Wear Resistance low-recoil pistol with an easy- to-manipulate slide that shoots • Enhanced Corrosion Protection comfortably regardless of your hand size or strength. -

Walther P22 Manual

anl_usa.qxd 29.04.2002 10:58 Seite 1 extractor stabilizer manual Loaded chamber frontsight slide rear sight hammer safety indicator barrel trigger lock muzzle manual trigger safety slide stop mounting rail takedown lever backstrap magazine catch Semi-Automatic pistol P22 grip magazine Cal. .22l.r. Operating instructions USA anl_usa.qxd 29.04.2002 10:58 Seite 2 Important instructions for the use of firearms Table of contents page It should be remembered that even the safest gun is poten- Components.............................................................1 tially dangerous to you and others when it is not properly handled. General...................................................................2 First of all read and understand the operating instructions Operation of safeties...................................................3-4 and learn how the weapon works and is to be Inspections ....................................................................5 handled.Always treat an unloaded weapon as if it were loaded. Loading the pistol...........................................................6 Insertion of the first cartridge......................................6 Always bear in mind: Keep your finger away Firing........................................................................7 from the trigger unless you really intend to Decocking the hammer...............................................7 fire. Always keep your weapon pointing in a Pistol with empty magazine............................................7 safe direction so that you -

1 Walther P22 22 Pistol Semi Auto New In

1 Walther P22 22 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box - Two Tone Nickel 2 Beretta PX4 Storm 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 3 Ruger LCR 38 Pistol Revolver New in Box 4 SCCY CPX-3 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 5 Taurus 709 Slim 9mm Pistol Semi Auto USED - No box 6 Taurus PT24/7 40 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 7 Taurus Judge 45 / 410 Pistol Semi Auto USED - No box 8 Charter Bulldog 44 Pistol Revolver New in Box 9 FN FNX 9mm Pistol Semi Auto USED Two Tone 10 Keltec P11 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 11 Walther PK380 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box - 2 Tone 12 Astra Astra Police 38 Pistol Revolver New in Box 13 S&W 638-3 38 Pistol Revolver New in Box 14 Bersa BP380CC 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 15 FN FNS 40 Pistol Semi Auto USED 16 I.O. Inc. Hellcat 380 Pistol Semi Auto New in Box American New in Box 17 Ruger Compact 9mm Pistol Semi Auto 18 Ruger Security 9 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box 19 S&W M&P C 9mm Pistol Semi Auto New in Box - Safety Model 20 Sig Sauer P290 9mm Pistol Semi Auto USED - Two Tone with 2 mags 21 Mossberg 500 12g Shotgun Pump Combo, 28" barrel and 18" barrel 22 Western Field M550A 12g Shotgun Pump New/No Box 23 Huglu 12g Shotgun SXS New/No Box Folding Single Barrel New/No Box 24 H&R 12g Shotgun 25 Henry Acubolt 22MAG Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 26 Marlin XT-22MR 22 WMR Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 27 Remington 700 30-06 Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 28 Remington 783 270 Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 29 Savage 11F 308 WIN Rifle Bolt Action New in Box 30 Henry Golden Boy 17HMR Rifle Lever Action New in Box 31 Marlin 60 22LR Rifle -

Pistol 214-243

Items Slides PISTOL INDEX FRONTCUT SLIDES FOR GLOCK® 43 & 48 RMR SLIDE FOR GLOCK® Barrels ........................ 220-223 Magazines & Parts ............. 227-232 Window Slide Maximize the Performance of Stainless Steel Slide With a Bundle of Custom Features Frames/Slides ...................214-220 Magwells ..................... 224-225 Your Pocket Glock® With an ® Upgraded "Top Half" Our RMR Slides for Glock Grips & Screws ................ 241-243 Safeties............................. 223 pistols feature a distinctive, With our Front-Cut Slide in- wraparound serration pattern Guide Rods ................... 223-224 Springs ....................... 232-234 stalled, you'll find your pocket that aids in manipulating the RMS/RMSC slide, especially when checking PISTOL Glock® becomes easier to oper- Cut Slide Ignition Parts.................. 240-241 Triggers & Components......... 234-240 ate without any change in its reli- the chamber. (OK, we’ll admit ability or size. The G43's greatest it: the serrations look cool, too.) Mag & Slide Releases........... 225-226 strength is that it lets you carry a They also come with a pre-cut slot for easy, secure, low-profile pistol with 6 rounds of centerfire mounting of a Trijicon RMR sight. All Front Cut RMR Slides also have Blank Slide punch in an ultra-compact EDC standard Glock factory front and rear sight dovetails for "iron" sights. package. The downside is the Since the RMR sits low, it can easily co-witness with iron sights. In G43's such a small pistol (barely 6" addition, you can get your Front Cut RMR Slide with an optional "window" cutout on top between the front serrations that reduces ® OAL), you can have trouble getting a firm grasp on the slide to rack SLIDES FOR FOR GLOCK 17/19/34 19LS EXTENDED SLIDE FOR it. -

Lanza Spreadsheet.Pdf

AB C D E F G H IJ KL M NO P Q 1 Killed Injured Name Weapons Location City Province Nation Day of the Week Month Day Year Ending Status Age Gender Firearms 2 57 35 Woo Bum-kon x2 M2 Carbine; grenades Town Uiryeong County Gyeongsangnam South Korea Monday-Tuesday April 26-27 1982 Suicide Dead 27 Male Police 3 57 (21/36) ? William Unek axe/rifle; axe Town Mahagi/Malampaka ?/? Belgian Congo/Tanganyika ?/Monday ?/February ?/11 1954/1957 Accident Dead ? Male Police 4 35 21 Martin Bryant semi-automatic L1A1 SLR; Colt AR-15; Daewoo USAS-12 Restaurant/Town Port Arthur Tasmania Australia Sunday-Monday April 18-19 1996 Accident Incarcerated 28 Male Illegally bought legal firearm/s 5 34 ? Ahmed Bragimov rifle Town Mekenskaya Chechnya Russia Friday October 8 1999 Killed by civilians Dead ? Male ? 6 32 17 Cho Seung-Hui Glock 19; Walther P22 School (University) Blacksburg Virginia United States Monday April 16 2007 Suicide Dead 23 Male Illegally bought legal firearm/s 7 30 15 Campo Delgado .32 revolver; hunting knife Apartment/Restaurant Bogota Cundinamarca Colombia Thursday December 4 1986 Suicide or killed by police Dead 52 Male ? 8 30 3 Mutsuo Toi Browning shotgun; sword; axe Town Kaio Okayama Japan Saturday May 21 1938 Suicide Dead 21 Male Illegally possessed legal firearm/s 9 29 Scores Baruch Goldstein IMI Galil Religious (Mosque) Hebron Hebron West Bank Friday February 25 1994 Killed by civilians Dead 37 Male Military 10 23 20 George Hennard Glock 17; Ruger P89 Restaurant Killeen Texas United States Wednesday October 16 1991 Suicide Dead 35 Male -

WALTHER-2019-CATALOG.Pdf

KEY FEATURES: • PRECISION MACHINED STEEL FRAME • QUICK DEFENSE TRIGGER • FULL LENGTH PICATINNY DUST COVER • PORTED SLIDE • OPTICS MOUNTING SYSTEM • MATCH GRADE ACCURACY • EXTENDED BEAVERTAIL QUICK DEFENSE TRIGGER With the creation of the PPQ came the Quick Defense trigger from Walther. Providing the shooter an alternative to the heavy, spongy striker-fired guns on the market. The Quick Defense trigger is a safe two-stage trigger with a crisp-break, and short-reset. The first stage allows for consistent prep with a distinct wall that can be easily found under stressful situations. The second stage is the crisp break of the wall, resulting in accurate shots on target. The reset of the Quick Defense trig- ger measures only 1/10", allowing the shooter to skip the first stage of the trigger completely and fire the follow up shot by only moving their finger 1/10 of an inch. Resulting in faster, more accu- rate and consistent shots on target. Q5 MATCHGERMAN CRAFTSMANSHIP WALTHER STEEL FRAME® - BE THE ENVY BE THE ENVY The Q5 Match Steel Frame offers an alternative to the flat, square styling of the competition. Providing the shooter with a precision machined steel frame and a ported slide, this gun delivers the quality and performance needed to win at the highest levels, while still providing the style and attention-to-detail to make you the envy at any range. OPTICS MOUNTING PLATE SPECIFICATIONS: Model: 2830001 2830418 Caliber: 9mm 9mm Finish: Tenifer Tenifer Magazines Included: 3 3 Barrel: (Length - Twist) 5" - 1/10 5" - 1/10 Trigger Pull: 5.6 lbs 5.6 lbs | 2019 PRODUCT CATALOG WALTHERARMS.COM Capacity: 15 rds 17 rds Overall Length: 8.7" 8.7" Height: 5.4" 5.9" Width: 1.3" 1.3" Sight Radius: 7.2" 7.2" Weight (empty mag): 41.6 oz 42.3 oz STEEL FRAME - FEATURES ALL STEEL CONSTRUCTION WITH EXTENDED FRAME RAILS AMBIDEXTROUS SLIDE STOP: Slide locks back on empty magazine.