Download Date 02/10/2021 14:10:01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

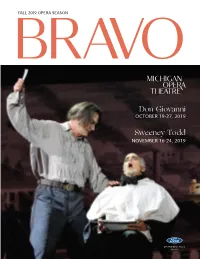

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Emerging Artist Recital: Chautauqua Opera Young Artist Program

OPERA AMERICA emerging artist recitals CHAUTAUQUA OPERA YOUNG ARTIST PROGRAM MARCH 14, 2019 | 7:00 P.M. UNCOMMON WOMEN Kayla White, soprano Quinn Middleman, mezzo-soprano Sarah Saturnino, mezzo-soprano Miriam Charney and Jeremy Gill, pianists PROGRAM A Rocking Hymn (2006) Gilda Lyons (b. 1975) Poem by George Wither, adapted by Gilda Lyons Quinn Middleman | Miriam Charney 4. Canción de cuna para dormir a un negrito Poem by Ildefonso Pereda Valdés 5. Canto negro Poem by Nicolás Guillén From Cinco Canciones Negras (1945) Xavier Montsalvatge (1912–2002) Sarah Saturnino | Miriam Charney Lucea, Jamaica (2017) Gity Razaz (b. 1986) Poem by Shara McCallum Kayla White | Jeremy Gill Die drei Schwestern From Sechs Gesänge, Op. 13 (1910–1913) Alexander von Zemlinsky (1871–1942) Poem by Maurice Maeterlinck Die stille Stadt From Fünf Lieder (1911) Alma Mahler (1879–1964) Poem by Richard Dehmel Quinn Middleman | Jeremy Gill [Headshot, credit: Rebecca Allan] Rose (2016) Jeremy Gill (b. 1975) Text by Ann Patchett, adapted by Jeremy Gill La rosa y el sauce (1942) Carlos Guastavino (1912–2000) Poem by Francisco Silva Sarah Saturnino | Jeremy Gill Sissieretta Jones, Carnegie Hall, 1902: O Patria Mia (2018) George Lam (b. 1981) Poem by Tyehimba Jess Kayla White | Jeremy Gill The Gossips From Camille Claudel: Into the Fire (2012) Jake Heggie (b. 1961) Text by Gene Scheer Sarah Saturnino | Jeremy Gill Reflets (1911) Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) Poem by Maurice Maeterlinck Au pied de mon lit From Clairières dans le ciel (1913–1914) Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) Poem by Francis Jammes Quinn Middleman | Miriam Charney Minstrel Man From Three Dream Portraits (1959) Margaret Bonds (1913–1972) Poem by Langston Hughes He had a dream From Free at Last — A Portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr. -

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Mattiwilda Dobbs Janzon

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Mattiwilda Dobbs Janzon Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Janzon, Mattiwilda Dobbs, 1925-2015 Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Mattiwilda Dobbs Janzon, Dates: March 1, 2005 Bulk Dates: 2005 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:25:17). Description: Abstract: Opera singer Mattiwilda Dobbs Janzon (1925 - 2015 ) was the first African American woman to appear in a principal role at La Scala Opera House in Milan. Dobbs also desegregated the San Francisco Opera Company and performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Dobbs passed away on December 8, 2015 in Atlanta, Georgia. Janzon was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on March 1, 2005, in Arlington, Virginia. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2005_056 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Opera singer Mattiwilda Dobbs was born on July 11, 1925 in Atlanta, Georgia. The fifth of six daughters, she sang her first solo at age six and began her musical studies in piano during Dobbs’ childhood. A member of the last graduating class from Atlanta University Lab School, Dobbs earned her high school diploma in 1942. Receiving her B.A. degree in music from Spelman College in 1946, Dobbs began her formal voice training under the direction of Naomi Maise and Willis Laurence James. After graduating, she studied with Lotte Leonard and Pierre Bernac and attended the Mannes College of Music and the Berkshire Music Center’s Opera Workshop. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

Sissieretta Jones Opera

Media Release For Immediate Release Lecture and Recital Celebrate America’s First Black Superstar: Sissieretta Jones Opera Providence presents a lecture and a talk-back about the great Black Diva, Sissieretta Jones of Providence, Rhode Island. Maureen Lee, the foremost scholar on Jones, will discuss how Jones built her international career and navigated the pitfalls of racists and opportunists in 19 th -century America. Lee, author of Sissieretta Jones: “The Greatest Singer of Her Race,” 1868-1933 , will excavate Jones’ world in Black Vaudeville, classical music, her remarkable ability at self-promotion, and her international acclaim singing for presidents and kings. The talk will take place Friday, April 26, 2013, 5:30pm at The Old Brick School House, 24 Meeting Street in Providence, RI. An exhibit of artifacts related to Jones’ singing career will be on display. On Saturday, April 27 at 2 p.m., vocalist Cheryl Albright will sample songs from Jones’ vast and varied repertoire in a recital at the historic Congdon Street Baptist Church, 17 Congdon Street, Providence, RI, where Jones worshipped and sang. Ms. Albright will be accompanied by pianist Rod Luther. The lecture and recital are made possible through a generous grant from the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities. Both events are free and open to the public. Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones of Providence, whose stage name, “Black Patti,” likened her to the renowned Spanish-born opera diva Adelina Patti, was a celebrated African American soprano during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Serving as a role model for other African American stage artists who followed her, Jones became a successful performer despite the obstacles she faced from Jim Crow segregation. -

Caring for the Working Artist

HOSPITAL HOSPITAL SPRING 2011 FOR SPECIAL FOR 2010 ANNUAL REPORT SURGERY SPECIAL 535 EAST 70TH STREET SURGERY NEW YORK, NY 10021 212.606.1000 www.hss.edu HORIZON SPRING 2011 Horizon Founded in 1863, Hospital for Special Surgery is interna- tionally regarded as the leading center for musculoskeletal health, providing specialty care to individuals of all ages. The Hospital is nationally ranked #1 in orthopedics and #3 in rheumatology by U.S.News & World Report, and has been top ranked in the Northeast in both specialties for 20 consecutive years. Caring for the Working Artist AA68100_A_CVR.indd68100_A_CVR.indd 1 44/11/11/11/11 111:05:191:05:19 AAMM They inspire us with their art. They astound us with their talents. At times, they seem superhuman such is their creative genius or the magnitude of their performance. But actors, artists, sculptors, musicians, and dancers are as human as the rest of us. Their bones break, their muscles fail, and their joints creak and give them pain. Perhaps they suffer more than others given the physical demands that their chosen professions often place on their bodies. While their gifts are many and varied, these artists share an intense devotion to their careers. And if they are impaired by an illness or an injury, they are equally as motivated in their desire to recover. That is why these working artists come to Hospital for Special Surgery. They know we will treat them as we do all of our patients – providing the best musculoskeletal care available in the world today. With the construction of three CA Technologies Rehabilitation new fl oors atop Hospital for Center and the Pharmacy Special Surgery due to be Department on the 9th fl oor. -

Spring 2006 Music

Music Today Spring 2006 at Iowa State University The ISU Wind Ensemble conducted by Michael Golemo. ISU alumnus and U.S. Poet Laurette Ted Kooser. ISU sound Omaha bound Third ISU President’s Concert to feature world premiere of alumnus’ poem set to music. he piece isn’t very long, third President’s Concert on Symphony Orchestra are also on only about four minutes. Sunday, March 26. A biennial the program. The Wind T But it’s a composition that event, this year’s President’s Ensemble will premiere an James Rodde, the Louise Moen Concert will be held at the new original fanfare composed by Professor of Music and director Holland Performing Arts Center Jeffrey Prater, professor of music. of choral activities, feels will stay in Omaha, Neb. Simon Estes, the F. Wendell with individuals for a long time. “The President’s Concerts Miller Distinguished Artist-in- “I can see this poem in a have spread interest for the music Residence, will be featured with beautiful new light,” Rodde says. program across campus,” Rodde the Symphony Orchestra and “It’s a well-written, expressive said. “It’s nice to have other Wind Ensemble. composition.” University-wide activities The concert gives students in The piece is a new work by surrounding this event and the three ensembles an René Clausen entitled The Early realize the Department of Music opportunity not only to give a Bird. It is a setting of a poem by is the catalyst that will draw the joint concert but also to perform Ted Kooser, current U.S. -

MU 270/Voice

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona COURSE SYLLABUS MU 270 - Performance Seminar/VOICE –Spring 2014 Time and Location: T 1-1:50 Bldg. 24-191 Instructor/ office: Lynne Nagle; Bldg. 24 – 155 and 133 Office Hours: M 9:30-10:30; T11:00-12:00; T 4:00-5:00; others TBA Phone: (909) 869-3558 e-mail: [email protected] Textbook and Supplies: No textbook is needed; notebook required. Course Objectives: To provide a laboratory recital situation wherein students may perform for each other, as well as for the instructor, for critical review. They will share song literature, musical ideas, production techniques, stylistic approaches, etc., in order to learn from each other as well as from the instructor. Assignments and Examinations:!In-class performances: You will be expected to perform a minimum of 3 times (5 for upper division) during each quarter, each performance taking place on a different day. Songs may be repeated for performance credit, but lower division students must perform at least 3 different songs and upper division at least 4 different songs. Please provide a spoken translation when performing in a foreign language. A brief synopsis of an opera, musical or scene is also appropriate if time allows. ALL PERFORMANCES IN SEMINAR ARE TO BE MEMORIZED except for traditional use of the score for oratorio literature. You are also expected to contribute to the subsequent discussion. Concert Reports: TWO (2) typed reports on choral/vocal concerts, recitals or shows must be submitted by week 10 seminar or sooner. You may use any concert you have attended since the end of the previous quarter. -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

2017 Convention Schedule

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 4 2:00PM – 5:00PM Board of Directors Meeting Anacapa 6:00PM - 9:00PM Pre-Conference Dinner & Wine Tasting Villa Wine Bar 618 Anacapa Street, Santa Barbara 7:00PM – 10:00PM Opera Scenes Competition Rehearsal Grand Ballroom THURSDAY, JANUARY 5 8:00AM – 5:00PM Registration Grand Foyer 9:00AM – 5:00PM EXHIBITS Grand Foyer 9:00AM – 9:30AM MORNING COFFEE Grand Foyer Sponsored by the University of Colorado at Boulder College of Music 9:30AM-10:45AM Sierra Madre The 21st Century Way: Redefining the Opera Workshop Justin John Moniz, Florida State University Training programs have begun to include repertoire across varying genres in order to better equip young artists for prosperous careers in today’s evolving operatic canon. This session will address specific acting and movement methods geared to better serve our current training modules, offering new ideas and fresh perspectives to help redefine singer training in the 21st century. Panelists include: Scott Skiba, Director of Opera, Baldwin Wallace Conservatory; Carleen Graham, Director of HGOco, Houston Grand Opera; James Marvel, Director of Opera, University of Tennessee-Knoxville; Copeland Woodruff, Director of Opera Studies, Lawrence University. 11:00AM-12:45PM Opening Ceremonies & Luncheon Plaza del Sol Keynote Speaker: Kostis Protopapas, Artistic Director, Opera Santa Barbara 1:00PM-2:15PM The Janus Face of Contemporary American Opera Sierra Madre Barbara Clark, Shepherd School of Music, Rice University The advent of the 21st century has proven fertile ground for the composition -

Montgomery Aviation: a Rising Hoosier Star Grand Rapids, Michigan Texas Jet, Inc

2nd Quarter 2010 MMontgomeryontgomery AAviationviation A RRisingising HHoosieroosier SStartar Also Inside • IIndustryndustry AuditAudit Standards:Standards: FFactact oorr FFiction?iction? • TThehe EEU’sU’s SSchemecheme ttoo RReduceeduce CCarbonarbon EEmissionsmissions • BBuildinguilding CommunityCommunity andand AirportAirport RRelations:elations: IIdeasdeas YouYou CanCan ImplementImplement Permit No. 1400 No. Permit Silver Spring, MD Spring, Silver PAID U.S. Postage Postage U.S. Standard PRESORT PRESORT 1307*%*/('6&-"/%4&37*$&4505)&(-0#"-"7*"5*0/*/%6453: $POUSBDU'VFMt1JMPU*ODFOUJWF1SPHSBNTt'VFM2VBMJUZ"TTVSBODFt3FGVFMJOH&RVJQNFOUt"WJBUJPO*OTVSBODFt'VFM4UPSBHF4ZTUFNT tXXXBWGVFMDPNtGBDFCPPLDPNBWGVFMtUXJUUFSDPN"7'6&-UXFFUFS 2nd Quarter 2010 Aviation ISSUE 2 | VOLUME 8 Business Journal Offi cial Publication of the National Air Transportation Association Chairman of the Board President Kurt F. Sutterer James K. Coyne Midcoast Aviation, Inc. NATA Cahokia, Illinois Alexandria, Virginia Vice Chairman Treasurer James Miller Bruce Van Allen Flight Options BBA Aviation Flight Support Cleveland, Ohio The EU’s Scheme to Reduce Carbon Emissions Orlando, Florida By Michael France 22 Immediate Past Chairman This year marks the beginning of aviation’s inclusion into the Dennis Keith European Union’s Emission Trading Scheme, which is basically Jet Solutions LLC Europe’s version of a market-based approach to the reduction of Richardson, Texas greenhouse gas emissions. U.S.-based aircraft operators who fl y into, Board of Directors out of, or between EU airports will be affected. Charles Cox Chairman Emeritus Northern Air Inc. Reed Pigman Montgomery Aviation: A Rising Hoosier Star Grand Rapids, Michigan Texas Jet, Inc. By Paul Seidenman and David J. Spanovich 25 Fort Worth, Texas When Andi and Dan Montgomery took the plunge into the FBO Todd Duncan business at Indianapolis Executive Airport (TYQ) in 2000, it was Duncan Aviation Ann Pollard an especially risky business given that neither had any prior FBO Lincoln, Nebraska Shoreline Aviation experience.