Lecture 3 Page 1 Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Photography and Visual Observations

CASE c o ANALYSIS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND VISUAL OBSERVATIONS NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AN_SP.A_E NASA SP-232 ANALYSIS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND VISUAL OBSERVATIONS COMPILED BY NASA MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER Scientific and Technical ln[ormation Office 19"I Is, S._. NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION Washington, D.C. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Price $4.25 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-606239 Foreword The Apollo 10 mission was a vital step toward the national goal of landing men on the Moon and returning them safely to Earth. This mission used the first complete Apollo spacecraft flown in lunar orbit and took men closer to the Moon than ever before. The mission clearly demonstrated that the Nation was ready to embark with the Apollo 11 crew on the voyage that has been the dream of men for thousands of years. Each Apollo lunar mission acquires photographs of areas on the Moon never before seen in such great detail. This report provides only a small sample of the types of analysis that can be performed with this photography. Even more important, however, this report provides scientists throughout the world with a knowledge of what new lunar photography is available and how the photograph can be obtained. It is hoped that more extensive analysis of this photography will continue, and it is certain that the photographs will be used for many decadesl RICHARD J. ALLENBY 01_ice of Manned Space Flight 111 Contents Page INTRODUCTION ........................................ vii Jamcs H. Sasser CHAPTER 1. VISUAL OBSERVATIONS ............. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Planetary Surfaces

Chapter 4 PLANETARY SURFACES 4.1 The Absence of Bedrock A striking and obvious observation is that at full Moon, the lunar surface is bright from limb to limb, with only limited darkening toward the edges. Since this effect is not consistent with the intensity of light reflected from a smooth sphere, pre-Apollo observers concluded that the upper surface was porous on a centimeter scale and had the properties of dust. The thickness of the dust layer was a critical question for landing on the surface. The general view was that a layer a few meters thick of rubble and dust from the meteorite bombardment covered the surface. Alternative views called for kilometer thicknesses of fine dust, filling the maria. The unmanned missions, notably Surveyor, resolved questions about the nature and bearing strength of the surface. However, a somewhat surprising feature of the lunar surface was the completeness of the mantle or blanket of debris. Bedrock exposures are extremely rare, the occurrence in the wall of Hadley Rille (Fig. 6.6) being the only one which was observed closely during the Apollo missions. Fragments of rock excavated during meteorite impact are, of course, common, and provided both samples and evidence of co,mpetent rock layers at shallow levels in the mare basins. Freshly exposed surface material (e.g., bright rays from craters such as Tycho) darken with time due mainly to the production of glass during micro- meteorite impacts. Since some magnetic anomalies correlate with unusually bright regions, the solar wind bombardment (which is strongly deflected by the magnetic anomalies) may also be responsible for darkening the surface [I]. -

Warren and Taylor-2014-In Tog-The Moon-'Author's Personal Copy'.Pdf

This article was originally published in Treatise on Geochemistry, Second Edition published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non- commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Warren P.H., and Taylor G.J. (2014) The Moon. In: Holland H.D. and Turekian K.K. (eds.) Treatise on Geochemistry, Second Edition, vol. 2, pp. 213-250. Oxford: Elsevier. © 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Author's personal copy 2.9 The Moon PH Warren, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA GJ Taylor, University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, HI, USA ã 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. This article is a revision of the previous edition article by P. H. Warren, volume 1, pp. 559–599, © 2003, Elsevier Ltd. 2.9.1 Introduction: The Lunar Context 213 2.9.2 The Lunar Geochemical Database 214 2.9.2.1 Artificially Acquired Samples 214 2.9.2.2 Lunar Meteorites 214 2.9.2.3 Remote-Sensing Data 215 2.9.3 Mare Volcanism -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

By DWG Arthur, Alice P. Agnieray, Ruth H. Pellicori, CA Wood, and T

No. 50 THE SYSTEM OF LUNAR CRATERS, QUADRANT III by D. W. G. Arthur, Alice P. Agnieray, Ruth H. Pellicori, C. A. Wood, and T. Weller February 25, 1965 ABSTRACT The designation, diameter, position, central peak information, and state of completeness are listed for each discernible crater with a diameter exceeding 3.5 km in the third lunar quadrant. The catalog contains about 5200 items and is illustrated by a map in 11 sections. on the averted lunar hemisphere, and therefore, these Thistem Communication of Lunar Craters, is the which third is part a catalog of The in Sys four are not listed in the catalog. parts of all craters recognizable with reasonable The approximate positions and diameters for certainty on photographs and having a diameter these craters are: greater than 3.5 km. It is thus a continuation of the work in Comm. LPL Nos. 30 and 40, and the same Long. Lat. Diam, (.00Ir) Hausen -91?5 - 6 5 ? 6 9 9 . 5 conventions and format are used. Boltzmann -96?0 - 7 5 ? 5 3 9 . 1 As in the earlier parts, it was found necessary S t e f a n - 9 4 ? 0 - 7 2 ? 0 7 8 . 0 to add names for large craters in the extreme limb regions. The new crater names for Quadrant III are: The above are mere additions to the Blagg and Miiller scheme. A more notable innovation, which Baade German-American astronomer has already been authorized by the International Boltzmann Austrian physicist Astronomical Union at its 1964 general meeting at Drygalski German geographer Hamburg, is the addition of the name Mare Cogni- Hartwig German selenodetist tum (the known sea) for the dark area between Krasnov Russian selenodetic observer Riphaeus and the crater Guerike. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

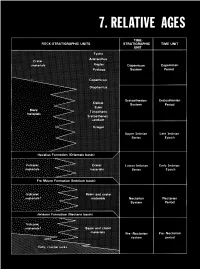

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

Celebrate Apollo

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Celebrate Apollo Exploring The Moon, Discovering Earth “…We go into space because whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share. … I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth. No single space project in this period will be more exciting, or more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish …” President John F. Kennedy May 25, 1961 Celebrate Apollo Exploring The Moon, Discovering Earth Less than five months into his new administration, on May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy, announced the dramatic and ambitious goal of sending an American safely to the moon before the end of the decade. Coming just three weeks after Mercury astronaut Alan Shepard became the first American in space, Kennedy’s bold challenge that historic spring day set the nation on a journey unparalleled in human history. Just eight years later, on July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong stepped out of the lunar module, taking “one small step” in the Sea of Tranquility, thus achieving “one giant leap for mankind,” and demonstrating to the world that the collective will of the nation was strong enough to overcome any obstacle. It was an achievement that would be repeated five other times between 1969 and 1972. By the time the Apollo 17 mission ended, 12 astronauts had explored the surface of the moon, and the collective contributions of hundreds of thousands of engineers, scientists, astronauts and employees of NASA served to inspire our nation and the world. -

Moon Viewing Guide

MMoooonn MMaapp What lunar features can you find? Use this Moon Map & Viewing Guide to explore different areas of the Moon - no binoculars needed! MMoooonn VViieewwiinngg GGuuiiddee A quick look at the Moon in the night sky – even without binoculars - shows light areas and dark areas that reveal lunar history. Can you find these features? Use the Moon Map (above) to help. Sea of Tranquility (Mare Tanquilitatus) – Formed when a giant t! nd I asteroid hit the Moon almost 4 billion years ago, this 500-mile wide Fou dark, smooth, circular basin is the site of the Apollo 11 landing in 1969. Sea of Rains (Mare Imbrium) – Imbrium Basin is the largest t! nd I basin on the Moon that was formed by a giant asteroid almost 4 Fou billion years ago. Sea of Serenity (Mare Serenitatis) – Apollo 17 astronauts t! sampled some of the oldest rocks on the Moon from edges of nd I Fou the Sea of Serenity. These ancient rocks formed in the Moon’s magma ocean. Lunar Highlands – The lighter areas on the Moon are the lunar t! highlands. These are the oldest regions on the Moon; they formed nd I Fou from the magma ocean. Because they are so old, they have been hit by impact craters many times, making the highlands very rough. Want an extra challenge? If you have a telescope or pair of binoculars, try finding these features: Appenine Mountains (Montes Apenninus) – Did you know there are mountain ranges on the Moon? The rims of the craters and t! nd I basins rise high above the Moon’s surface. -

Lunar Exploration Efforts

Module 3 – Nautical Science Unit 4 – Astronomy Chapter 13 - The Moon Section 1 – The Moon What You Will Learn to Do Demonstrate understanding of astronomy and how it pertains to our solar system and its related bodies: Moon, Sun, stars and planets Objectives 1. Recognize basic facts about the Moon such as size, distance from Earth and atmosphere 2. Describe the geographical structure of the Moon 3. Describe the surface features of the Moon 4. Explain those theories that describe Moon craters and their formations Objectives 5. Describe the mountain ranges and riles on the surface of the Moon 6. Explain the effect moonquakes have on the Moon 7. Describe how the Moon’s motion causes its phases 8. Explain the basic reasons for Moon exploration Key Terms CPS Key Term Questions 1 - 12 Key Terms Maria - Mare or Maria (plural); Any of the several dark plains on the Moon and Mars; Latin word for “Sea” Reflectance - The ratio of the intensity of reflected radiation to that of the radiation that initially hits the surface. Key Terms Impact Crater - The cup shaped depression or cavity on the surface of the Earth or other heavenly bodies. Breccia - Rock composed of angular fragments of older rocks melded together as a result of a meteor impact. Regolith - The layer of disintegrated rock fragments (dust), just above the solid rock of the Moon’s crust. Key Terms Rilles - Cracks in the lunar surface similar to shallow, meandering river beds on the Earth. Phases The Moon’s motion in its orbit (of the Moon) - causes its phases (progressive changes in the visible portion of the Moon). -

Blasts from the Past Historic Supernovas

BLASTS from the PAST: Historic Supernovas 185 386 393 1006 1054 1181 1572 1604 1680 RCW 86 G11.2-0.3 G347.3-0.5 SN 1006 Crab Nebula 3C58 Tycho’s SNR Kepler’s SNR Cassiopeia A Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese, Historical Observers: Chinese, Japanese Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European, Chinese, Korean Historical Observers: European? Arabic, European Arabic, Native American? Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Probable Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Possible Likelihood of Identification: Definite Likelihood of Identification: Definite Distance Estimate: 8,200 light years Distance Estimate: 16,000 light years Distance Estimate: 3,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,500 light years Distance Estimate: 13,000 light years Distance Estimate: 10,000 light years Distance Estimate: 7,000 light years Distance Estimate: 6,000 light years Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Core collapse of massive star? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf? Type: Core collapse of massive star Type: Thermonuclear explosion of white dwarf Type: Core collapse of massive star NASA’s ChANdrA X-rAy ObServAtOry historic supernovas chandra x-ray observatory Every 50 years or so, a star in our Since supernovas are relatively rare events in the Milky historic supernovas that occurred in our galaxy. Eight of the trine of the incorruptibility of the stars, and set the stage for observed around 1671 AD.