Site Selection and the Planning Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schools and Libraries 1Q2014 Funding Year 2013 Commitments - 3Q2013 Page 1 of 136

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL35 Schools and Libraries 1Q2014 Funding Year 2013 Commitments - 3Q2013 Page 1 of 136 Applicant Name City State Committed ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 6-1 ABERDEEN SD 32,793.60 ABERNATHY INDEP SCHOOL DIST ABERNATHY TX 19,385.14 ABSECON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT ABSECON NJ 13,184.40 Academia Bautista de Puerto Nuevo, Inc Rio Piedras PR 59,985.00 ACADEMIA SAN JORGE SAN JUAN PR 45,419.95 ACHIEVE CAREER PREPARATORY ACADEMY TOLEDO OH 19,926.00 ACHILLE INDEP SCHOOL DIST 3 ACHILLE OK 49,099.48 ADA PUBLIC LIBRARY ADA OH 900.00 AF-ELM CITY COLLEGE PREP CHARTER SCHOOL NEW HAVEN CT 31,630.80 AFYA PUBLIC CHARTER MIDDLE BALTIMORE MD 17,442.00 ALBANY CARNEGIE LIBRARY ALBANY MO 960.00 ALBIA COMMUNITY SCHOOL DIST ALBIA IA 26,103.24 ALBION SCHOOL DISTRICT 2 ALBION OK 16,436.20 ALEXANDRIA COMM SCHOOL CORP ALEXANDRIA IN 32,334.54 ALICE INDEP SCHOOL DISTRICT ALICE TX 293,311.41 ALL SAINTS ACADEMY WINTER HAVEN FL 14,621.51 ALL SAINTS CATHOLIC SCHOOL NORMAN OK 1,075.34 ALLEGHENY-CLARION VALLEY SCH DIST FOXBURG PA 15,456.00 ALPINE COUNTY LIBRARY MARKLEEVILLE CA 16,652.16 ALPINE SCHOOL DISTRICT AMERICAN FORK UT 279,203.16 ALTOONA PUBLIC LIBRARY ALTOONA KS 856.32 ALVAH SCOTT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL HONOLULU HI 4,032.00 AMHERST COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOL DIVISION AMHERST VA 245,106.00 AMSTERDAM CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT AMSTERDAM NY 96,471.00 ANTWERP LOCAL SCHOOL DISTRICT ANTWERP OH 22,679.24 ANUENUE SCHOOL HONOLULU HI 5,376.00 APPLE VALLEY UNIF SCHOOL DIST APPLE VALLEY CA 409,172.44 ARCHULETA CO SCHOOL DIST 50 PAGOSA SPRINGS CO 81,774.00 -

Sex Education in Mississippi

Sex Education in Mississippi: Why ‘Just Wait’ Just Doesn’t Work Sex Education in Mississippi: Why ‘Just Wait’ Just Doesn’t Work INTRODUCUTION……………………………………………………………………………....3 I. Federal Investment in Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sexuality Education Programs……………………………………………………………………………………..3 II. Adolescent Health in Mississippi……………………………………………………………..6 III. Mississippi Sex Education Law and Policy………………………………………………....…9 IV. Methodology of the Report…………………………………………………………..……...11 V. Figure 1. Map of Mississippi Public Health Districts……………………………..…………13 WHAT YOUNG PEOPLE ARE LEARNING IN MISSISSIPPI…………………..……………14 I. Federally Funded Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Programs in Mississippi …………....…..14 II. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage and Sex Education Programs in Mississippi Public Schools……………………………………………………………………………………...22 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………………………..30 APPENDIX 1. LIST OF MISSISSIPPI SCHOOL DISTRICTS THAT RECEIVED AND RESPONDED TO OUR PUBLIC RECORDS REQUEST…………………………….....32 REFERENCES …………………………………………………………………....……………..34 2 INTRODUCTION The federal government’s heavy investment in abstinence-only-until-marriage funding over the past few decades has promulgated a myriad of state policies, state agencies, and community-based organizations focused on promoting an abstinence-only-until-marriage ideology. The trickle-down effect of the funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs and the industry it created has impacted states throughout the nation, with a disparate impact on Southern states, including -

SOS Banner June-2014

A Special Briefing to the Mississippi Municipal League Strengthen Our Schools A Call to Fully Fund Public Education Mississippi Association of Educators 775 North State Street Jackson, MS 39202 maetoday.org Keeppublicschoolspublic.org Stay Connected to MAE! Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Ocean Springs Mayor Connie Moran Moderator Agenda 1. State funds that could be used for public education Rep. Cecil Brown (Jackson) 2. State underfunding to basic public school funding (MAEP) Sen. Derrick Simmons (Greenville) 3. Kindergarten Increases Diplomas (KIDs) Rep. Sonya Williams-Barnes (Gulfport) 4. The Value of Educators to the Community Joyce Helmick, MAE President 5. Shifting the Funding of Public Schools from the State to the Cities: The Unspoken Costs Mayor Jason Shelton (Tupelo) Mayor Chip Johnson (Hernando) Mayor Connie Moran (Ocean Springs) 8. Invest in Our Public Schools to Motivate, Educate, and Graduate Mississippi’s Students Superintendent Ronnie McGehee, Madison County School District Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com Sources of State Funding That Could Be Used for Public Schools As of April 2014 $481 Million Source: House of Representatives Appropriations Chairman Herb Frierson Investing in classroom priorities builds the foundation for student learning. Mississippi Association of Educators "Great Public Schools for Every Student" 775 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39202 | Phone: 800.530.7998 or 601.354.4463 Websites: MAEToday.org and KeepPublicSchoolsPublic.com From 2009 – 2015, Mississippi’s State Leaders UNDERFUNDED* All School Districts in Mississippi by $1.5 billion! They deprived OUR students of . -

21St Century Community Learning Grants in Mississippi

21st Century Community Learning Grants in Mississippi Grantee City Contact Award Year Year One Award Program Description Project JUMP 21st Century Community Learning Center serves students at Barr Elementary School, Jim Hill High School, and Lanier High School in an after-school program and various summer activities including Camp 100 Black Men of Jackson, Inc. Jackson Maxine Lyles 2004 $242,767 100, a seven week summer camp. The Consortium’s proposal is designed to address the needs of a two-county area (Alcorn and Prentiss) served by four public school districts. The project includes after- school and summer academic and enrichment programs Alcorn County School District Corinth Jean McFarland 2004 $448,354 and activities. The Amite County Community Learning Center Program consists of the following Components: Amite County School District Liberty Mary Russ 2004 $199,254 Before- and after-school and summer recess activities. Amory's project provides after-school and summer tutoring, enrichment, and literacy/media nights at all four school sites. Additionally, services are provided at one Amory School District Amory Susan Martin 2002 $461,096 community site and several faith-based sites. THIS GRANT ALLOWS US TO OFFER AFTER SCHOOL TUTORIALS FOR LOW PERFORMING STUDENTS AND OTHER STUDENTS IF THEY NEED Benoit School District BENOIT SUZANNE HAWLEY 2004 $109,341 ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTION. To provide a math & reading skill program to maintain or enhance present skill levels. Provide a program to develop self-discipline, and self-esteem.Help members Boys and Girls Club of Central develop skills to score proficiently or above on the Miss Mississippi Jackson Bob Ward 2004 $170,000 Curriculum Test. -

Mississippi House District As Adopted May 2, 2012 with Public School Districts (2012 TIGER)

Mississippi House District As Adopted May 2, 2012 With Public School Districts (2012 TIGER) House School District District Number Name 1 Alcorn School District 1 Corinth School District 1 Tishomingo County Schools 2 Alcorn School District 2 Corinth School District 3 Alcorn School District 3 Baldwyn School District 3 Booneville School District 3 Prentiss County School District 4 Alcorn School District 4 North Tippah School District 4 South Tippah School District 5 Benton County School District 5 Holly Springs School District 5 Lafayette County School District 5 Marshall County School District 5 Tate County School District 6 DeSoto County School District 7 DeSoto County School District 8 Lafayette County School District 8 Senatobia Municipal School District 8 Tate County School District 9 Coahoma County School District 9 Quitman County School District 9 Tate County School District 9 Tunica County School District 10 East Tallahatchie School District 10 Lafayette County School District 10 North Panola School District 10 Oxford School District 10 South Panola School District 11 North Panola School District 11 Senatobia Municipal School District 11 South Panola School District 11 Tate County School District 12 Lafayette County School District 12 Oxford School District 13 Benton County School District 13 Holly Springs School District 13 Lafayette County School District 13 Marshall County School District 13 Oxford School District 13 Union County School District 14 New Albany Public Schools 14 Union County School District 15 Pontotoc City Schools -

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi's Public School Districts

Appendix B: Maps of Mississippi’s Public School Districts This appendix includes maps of each Mississippi public school district showing posted bridges that could potentially impact school bus routes, noted by circles. These include any bridges posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and bridges posted for gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Included with each map is the following information for each school district: the total number of bridges in the district; the number of posted bridges potentially impacting school districts, including the number of single axle postings, number of gross weight postings, and number of tandem axle bridges; the number of open bridges that should be posted according to bridge inspection criteria but that have not been posted by the bridge owners; and, the number of closed bridges.1 PEER is also providing NBI/State Aid Road Construction bridge data for each bridge posted for single axle weight limits of up to 20,000 pounds and gross vehicle weight limits of up to 33,000 pounds. Since the 2010 census, twelve Mississippi public school districts have been consolidated with another district or districts. PEER included the maps for the original school districts in this appendix and indicated with an asterisk (*) on each map that the district has since been consolidated with another district. SOURCE: PEER analysis of school district boundaries from the U. S. Census Bureau Data (2010); bridge locations and statuses from the National Bridge Index Database (April 2015); and, bridge weight limit ratings from the MDOT Office of State Aid Road Construction and MDOT Bridge and Structure Division. -

Fiscal Year 2016 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - MISSISSIPPI

Fiscal Year 2016 Title I Grants to Local Educational Agencies - MISSISSIPPI FY 2016 Title I LEA ID District Allocation* 2800360 Aberdeen School District 783,834 2800390 Alcorn School District 916,360 2800420 Amite County School District 738,597 2800450 Amory School District 569,805 2800510 Attala County School District 552,307 2800540 Baldwyn School District 364,271 2800570 Bay St. Louis School District 983,511 2800690 Benoit School District 239,518 2800600 Benton County School District 542,028 2800630 Biloxi Public School District 2,051,430 2800820 Booneville School District 347,892 2800840 Brookhaven School District 1,359,723 2800870 Calhoun County School District 922,371 2800900 Canton Public School District 1,813,829 2800930 Carroll County School District 351,882 2800960 Chickasaw County School District 161,818 2800990 Choctaw County School District 710,829 2801020 Claiborne County School District 962,449 2801050 Clarksdale Municipal School District 2,394,213 2801080 Clay County School District 219,189 2800750 Cleveland School District 1,877,888 2801090 Clinton Public School District 919,113 2801110 Coahoma County School District 1,244,888 2801140 Coffeeville School District 337,445 2801170 Columbia School District 914,516 2801200 Columbus Municipal School District 2,695,637 2801220 Copiah County School District 1,111,014 2801260 Corinth School District 947,110 2801290 Covington County School District 1,354,830 2801320 DeSoto County School District 5,152,857 2801360 Durant Public School District 434,398 2801380 East Jasper School District -

Delta State University

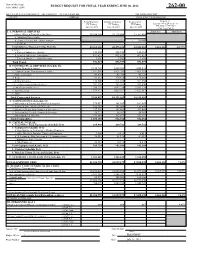

State of Mississippi BUDGET REQUEST FOR FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2014 Form MBR-1 (2009) 262-00 DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY - ON CAMPUS CLEVELAND MS DR JOHN HILPERT AGENCY ADDRESS CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Actual Expenses Estimate Expenses Requested for Requested FY Ending FY Ending FY Ending Increase (+) or Decrease (-) FY 2014 vs. FY 2013 June 30, 2012 June 30, 2013 June 30, 2014 (Col. 3 vs. Col. 2) I. A. PERSONAL SERVICES AMOUNT PERCENT 1. Salaries, Wages & Fringe Benefits (Base) 28,368,386 30,278,694 33,561,810 a. Additional Compensation b. Proposed Vacancy Rate (Dollar Amount) ( 20,000) c. Per Diem Total Salaries, Wages & Fringe Benefits 28,368,386 30,278,694 33,541,810 3,263,116 10.77% 2. Travel a. Travel & Subsistence (In-State) 133,503 132,153 132,153 b. Travel & Subsistence (Out-of-State) 431,622 431,622 431,622 c. Travel & Subsistence (Out-of-Country) 9,802 9,802 9,802 Total Travel 574,927 573,577 573,577 B. CONTRACTUAL SERVICES (Schedule B): a. Tuition, Rewards & Awards 4,130,709 4,685,048 4,685,048 b. Communications, Transportation & Utilities 1,141,810 1,421,951 1,421,951 c. Public Information 43,470 43,729 43,729 d. Rents 233,832 170,610 170,610 e. Repairs & Service 336,400 511,036 511,036 f. Fees, Professional & Other Services 791,176 763,590 763,590 g. Other Contractual Services 1,290,729 1,092,774 1,092,774 h. Data Processing 1,579,971 1,624,917 1,624,917 i. -

Auditor's 2015 Report

PUBLIC EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM OF MISSISSIPPI Schedule of Employer Allocations and Schedule of Collective Pension Amounts June 30, 2015 (With Independent Auditors’ Report Thereon) KPMG LLP Suite 1100 One Jackson Place 188 East Capitol Street Jackson, MS 39201-2127 Independent Auditors’ Report The Board of Trustees Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi: We have audited the accompanying schedule of employer allocations of the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi (the System), as of and for the year ended June 30, 2015, and the related notes. We have also audited the columns titled net pension liability, total deferred outflows of resources excluding employer specific amounts, total deferred inflows of resources excluding employer specific amounts, and total pension expense excluding that attributable to employer-paid member contributions (specified column totals) included in the accompanying schedule of collective pension amounts of the System as of and for the year ended June 30, 2015, and the related notes. Management’s Responsibility for the Schedules Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these schedules in accordance with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of the schedules that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditors’ Responsibility Our responsibility is to express opinions on the schedule of employer allocations and the specified column totals included in the schedule of collective pension amounts based on our audit. We conducted our audit in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

06. Approval of Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation As Required by Senate Bill 2760

OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY Summary of State Board of Education Agenda Items October 18-19, 2012 OFFICE OF SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, OVERSIGHT AND RECOVERY 06. Approval of course of action for Bolivar County School District consolidation as required by Senate Bill 2760 Recommendation: Approval Back-up material attached 1 Course of Action for Bolivar County School District Consolidation 1. State Board should review comments from the October 15th meeting offered by the affected school districts and appoint a subcommittee to hear comments from each district regarding the eventual criteria that the SBE must adopt to guide the redistricting process. The subcommittee may hold a meeting with each district for the purpose of hearing comments regarding redistricting criteria. 2. SBE should review comments from the affected districts submitted by the subcommittee. 3. SBE should review comments from the community meetings at the January 18 meeting and may adopt official criteria for reapportionment and redistricting of the new consolidated school districts. 4. Draft maps will be delivered to the districts in Bolivar County as soon as they are prepared. 5. At the February 15 meeting, SBE can review all public comments or written information submitted. 6. SBE should adopt new board member districts for North Bolivar Consolidated School District, and West Bolivar Consolidated School District at the March meeting and submit the required information to the Department of Justice. 2 MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2012 By: Senator(s) -

FY2015 CFPA Preliminary Allocations

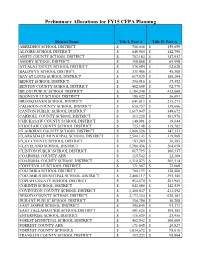

Preliminary Allocations for FY15 CFPA Planning District Name Title I, Part A Title II, Part A ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 706,046 $ 159,659 ALCORN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 649,965 $ 142,790 AMITE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 702,184 $ 147,952 AMORY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 358,868 $ 69,998 ATTALA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 576,084 $ 92,628 BALDWYN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 331,486 $ 45,308 BAY ST LOUIS SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 617,525 $ 188,294 BENOIT SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 250,910 $ 37,452 BENTON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 462,608 $ 92,779 BILOXI PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,184,246 $ 432,009 BOONEVILLE SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 180,022 $ 36,093 BROOKHAVEN SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 841,813 $ 215,273 CALHOUN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 630,757 $ 139,606 CANTON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,617,947 $ 349,672 CARROLL COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 313,220 $ 101,976 CHICKASAW COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 149,081 $ 19,644 CHOCTAW COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 725,148 $ 119,702 CLAIBORNE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,006,526 $ 147,353 CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 2,500,143 $ 319,988 CLAY COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 183,269 $ 36,585 CLEVELAND SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,280,438 $ 264,059 CLINTON PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 617,795 $ 166,337 COAHOMA COUNTY AHS$ 115,542 $ 22,309 COAHOMA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,310,073 $ 205,514 COFFEEVILLE SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 371,567 $ 72,068 COLUMBIA SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 700,193 $ 128,406 COLUMBUS MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 2,400,117 $ 395,145 COPIAH COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 914,570 $ 201,981 CORINTH SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 842,080 $ 142,539 COVINGTON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 1,400,047 $ 211,492 DESOTO COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT$ 3,172,354 -

Improving the Efficiency of Mississippi's School Districts

#589 Joint Legislative Committee on Performance Evaluation and Expenditure Review (PEER) Report to the Mississippi Legislature Improving the Efficiency of Mississippi’s School Districts: Phase Two School districts should apply a disciplined approach of identifying their needs so that cost savings can be effectively redirected into an area that will improve the district’s efficiency and academic performance. The Legislature’s current effort to revitalize performance budgeting requires increased accountability for the efficient and effective use of public resources, including the expenditure of tax dollars by the state’s public school districts. PEER sought to identify efficiency drivers and metrics utilized by fourteen selected school districts with the purpose of compiling a list of best practices that could be shared with other districts to yield efficiency improvements. PEER had proposed that by selecting districts that exhibited low support expenditures and high academic performance, as well as those districts that exhibited high support expenditures and low academic performance, distinct practices and procedures could be identified in order to establish drivers and metrics deemed as more efficient. By using an interview protocol based on school district efficiency review processes in other states, PEER targeted nine functional areas in the fourteen selected districts: district leadership and organization, financial management, human resources, purchasing and warehousing, educational service delivery, transportation, facilities, food service, and information technology. Three major themes were exhibited within the selected school districts. Regardless of whether the district was more efficient or less efficient (as defined by PEER in this report), no distinct efficiency drivers were identified that could be implemented as best practices.