ATMOSPHERES and AFFECT CONTENTS 3 Moana Nepia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatre Royal Including All of That Part of the Building

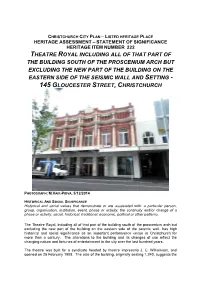

CHRISTCHURCH CITY PLAN – LISTED HERITAGE PLACE HERITAGE ASSESSMENT – STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HERITAGE ITEM NUMBER 222 THEATRE ROYAL INCLUDING ALL OF THAT PART OF THE BUILDING SOUTH OF THE PROSCENIUM ARCH BUT EXCLUDING THE NEW PART OF THE BUILDING ON THE EASTERN SIDE OF THE SEISMIC WALL AND SETTING - 145 GLOUCESTER STREET, CHRISTCHURCH PHOTOGRAPH: M.VAIR-PIOVA, 5/12/2014 HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE Historical and social values that demonstrate or are associated with: a particular person, group, organisation, institution, event, phase or activity; the continuity and/or change of a phase or activity; social, historical, traditional, economic, political or other patterns. The Theatre Royal, including all of that part of the building south of the proscenium arch but excluding the new part of the building on the eastern side of the seismic wall, has high historical and social significance as an important performance venue in Christchurch for more than a century. The alterations to the building and its changes of use reflect the changing nature and fortunes of entertainment in the city over the last hundred years. The theatre was built for a syndicate headed by theatre impresario J. C. Williamson, and opened on 25 February 1908. The size of the building, originally seating 1,240, suggests the popularity of theatre at the time. The building is the third in Gloucester Street to carry the name. Williamson was an American who settled in Australia, founding his company in 1879; many of the better productions which toured Australasia from the late nineteenth until the mid-twentieth centuries travelled were through Williamson. -

No. Forty One January 1972 President: Miles Warren. Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw

COA No. Forty one January 1972 president: Miles Warren. Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw. Exhibitions Officer: Tony Geddes. news The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts Receptionist: Jill Goddard. News Editor: A. J. Bisley. 66 Gloucester Street Telephone 67-261 Registered at the Post Office Headquarters, Wellington, as a magazine P.O. Box 772 Christchurch Bill Cummings—Oil Marlborough Sounds Series—Kohanga - Marlborough Sounds. March Brian Holmewood and Subject to Adjustment Gallery Calendar Elizabeth Hancock Art School Drawings To 6 January Phillippa Blair National Safety Posters Carl Sydow To 12 January 10 Big Paintings Peter Mardon 6-20 January Manawatu Prints Frits Krijgsman 8-21 January Touring Reproductions April Susan Chaytor Early N.Z. Painting Tom Taylor 26 January Architects (Preview) British Paintings - 13 February Cranleigh Barton Exhibitions mounted with the assistance of the 14-29 February Philip Trusttum Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council through the 11-27 February Annual Autumn Exhibition agency of the Association of N.Z. Art Societies. PAGE ONE C. W. GROVER President's Comment Landscape Design I write this as your new, green as grass presi And Construction dent much aware of the series of distinguished and talented people who have run the Society in the past and wondering if I will be able to 81 Daniels Rd, Christchurch measure up to them. I am quickly beginning to Phone 527-702 appreciate what it means in time and involve ment. Fortunately the Society is in the expert hands of its famous Tweedle-dee and Tweedle dum, the secretary and the treasurer who kindly help the new boy and gently tell him what to do. -

NEW ZEALAND Queenstown South Island Town Or SOUTH Paparoa Village Dunedin PACIFIC Invercargill OCEAN

6TH Ed TRAVEL GUIDE LEGEND North Island Area Maps AUCKLAND Motorway Tasman Sea Hamilton Rotorua National Road New Plymouth Main Road Napier NEW Palmerston North Other Road ZEALAND Nelson WELLINGTON 35 Route 2 Number Greymouth AUCKLAND City CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND Queenstown South Island Town or SOUTH Paparoa Village Dunedin PACIFIC Invercargill OCEAN Airport GUIDE TRAVEL Lake Taupo Main Dam or (Taupomoana) Waterway CONTENTS River Practical, informative and user-friendly, the Tongariro National 1. Introducing New Zealand National Park Globetrotter Travel Guide to New Zealand The Land • History in Brief Park Government and Economy • The People akara highlights the major places of interest, describing their Forest 2. Auckland, Northland ort Park principal attractions and offering sound suggestions and the Coromandel Mt Tongariro Peak on where to tour, stay, eat, shop and relax. Auckland City Sightseeing 1967 m Around Auckland • Northland ‘Lord of the The Coromandel Rings’ Film Site THE AUTHORS Town Plans 3. The Central North Island Motorway and Graeme Lay is a full-time writer whose recent books include Hamilton and the Waikato Slip Road Tauranga, Mount Maunganui and The Miss Tutti Frutti Contest, Inside the Cannibal Pot and the Bay of Plenty Coastline Wellington Main Road Rotorua • Taupo In Search of Paradise - Artists and Writers in the Colonial Tongariro National Park Seccombes Other Road South Pacific. He has been the Montana New Zealand Book The Whanganui River • The East Coast and Poverty Bay • Taranaki Pedestrian Awards Reviewer of the Year, and has three times been a CITY MALL 4. The Lower North Island Zone finalist in the Cathay Pacific Travel Writer of the Year Awards. -

Public Art in Central Christchurch

PUBLIC ART IN CENTRAL CHRISTCHURCH A STUDY BY THE ROBERT MCDOUGALL ART GALLERY 1997 Public Art In Central Christchurch A Study by the Robert McDougall Art Gallery 1997 Compiled by Simone Stephens Preface Christchurch has an acknowledged rich heritage of public art and historically, whilst it may not be able to claim the earliest public monument in New Zealand, it does have the earliest recognised commissioned commemorative sculpture in the form of the Godley statue by Thomas Woolner. This was unveiled in August 1867. Since that date the city has acquired a wide range of public art works that now includes fountains and murals as well as statues and sculpture. In 1983 the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, with the assistance of two researchers on a project employment scheme, undertook to survey and document 103 works of art in public places throughout Christchurch. Unfortunately even though this was completed, time did not permit in-depth research, or funding enable full publication of findings. Early in 1997, Councillor Anna Crighton, requested that the 1983 survey be reviewed and amended where necessary and a publication produced as a document describing public art in the city. From June until December 1997, Simone Stephens carried out new research updating records, as many public art works had either been removed or lost in the intervening fourteen years. As many of the more significant public art works of Christchurch are sited between the four Avenues of the inner city, this has been the focus of the 1997 survey the results of which are summarised within this publication. -

The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts 66

Mo. Forty-four 1972 President: Miles Warren The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts Secretary-Manager: Russell Laidlaw 66 Gloucester Street Telephone 67-261 Exhibitions Officer: Tony Geddes P.O. Box 772 Christchurch Receptionist: Joanna Mowat Registered et the Post Office Headquarters. Wellington as a magazine. News Editor: S. McMillan This photograph was taken during the exhibition of the New Zealand Institute of Architects gallery calendar (subject to adjustment) June — July 19 Graphic & Craft August W. A. Sutton & D. Blumhart. Univer November D. Holland July 1 - 17 Joanna Harris sity exhibition arranged through the Town & Country July 15 - Aug 2 Alan Clark & Barry Sharplin Engineering Library. The Group July 16-31 Michael Ebel September Neuman & Grant Technical Institute Graphic & Design July 21 - Aug 7 John Coley Annual Spring Exhibition Christeller. University exhibition July Gwen Morris. University exhibition G. Smith arranged through Engineering Library. arranged through the Engineering October Valerie Heinz December Helen Rockel Library. C. McCahon Junior Art Class J. Harris Open Exhibition Aug 1 - 17 V. Jamieson G. Bennett & M. Adams Fanning. University exhibition arranged Aug 3- 17 Star Secondary School G. Barton Weavers through the Engineering Library. Aug 9-24 Italian Graphics Building Fund Fair Aug 19 - Sept 7 Tony Geddes & Jonathan Mane D. Driver. University exhibition Exhibitions are mounted with the assistance of the Queen Aug 20 - Sept 7 Louise Henderson arranged through the Engineering Elizabeth 11 Arts Council through the agency of the Aug 27 - Sept 13 Olivia Spencer-Bower Library. Association of N.Z. Art Societies. new members Mrs K.C.Allen Mr Griffith Edgar Jones Mr Robin E. -

Heritage and Participation: a Case Study of Advocacy in Post- Earthquake Christchurch

Heritage and Participation: a case study of advocacy in post- earthquake Christchurch Rebecca Margaret Halliday Ford A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Museum and Heritage Studies Victoria University of Wellington June 2018 Abstract This dissertation explores the advocacy for the Christchurch Town Hall that occurred in 2012-2015 after the Canterbury Earthquakes. It frames this advocacy as an instance of collective-action community participation in a heritage decision, and explores the types of heritage values it expressed, particularly social values. The analysis contextualises the advocacy in post-quake Christchurch, and considers its relationship with other developments in local politics, heritage advocacy, and urban activism. In doing so, this dissertation considers how collective action operates as a form of public participation, and the practical implications for understanding and recognising social value. This research draws on studies of practices that underpin social value recognition in formal heritage management. Social value is held by communities outside institutions. Engaging with communities enables institutions to explore the values of specific places, and to realise the potential of activating local connections with heritage places. Such projects can be seen as participatory practices. However, these processes require skills and resources, and may not be appropriate for all places, communities and institutions. However, literature has under- studied collective action as a form of community participation in heritage management. All participation processes have nuances of communities, processes, and context, and this dissertation analyses these in one case. The research specifically asked what heritage values (especially social values) were expressed through collective action, what the relationship was with the participation processes, communities, and wider situation that produced them, and the impact on institutional rhetoric and decisions. -

The Acoustical Design of the Christchurch Town Hall

The acoustical design of the Christchurch town hall Harold Marshall Marshall Day Acoustics Ltd., P O Box 5811, Wellesley Str. 1141, Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract The Christchurch Town Hall (New Zealand) was opened on September 30 1972. Disastrous earthquakes hit Christchurch in September 2010 and February 2011. Most of the CBD and the historic buildings were destroyed or damaged by the February event, including much of the Town Hall complex. The City Council in November 2012, resolved to restore the entire building but at the time of writing there remains uncertainty. The intention of this paper is to put on record the history of the Christchurch Town Hall design in case it does not survive the political after-shocks of the earthquakes. With the building’s future now in jeopardy it seems appropriate to set out the process that led to this unique design, acknowledge the many contributors, outline its research base, the innovations in predictive technology employed, the evaluation of its acoustical properties and the learning that flowed from it. Reprinted with the kind permission of the Author and ‘Journal of Building Acoustics’ Volume 21 Number 1 2014 1. Introduction Only architects registered in NZ were permitted to enter. The first stage was to close on 31st January 1966. My role The design of the Christchurch Town Hall auditorium was as acoustical advisor to the competition Chairman, is inseparable from the discovery of the importance of Mr. Ron Muston, then President of the NZIA. At the lateral reflected sound in concert hall preference. Indeed same time I was preparing to go to the UK to the newly the Christchurch project provided the problem statement, formed Institute of Sound and Vibration Research at the hypothesis, testing and its initial application in a major Southampton University, on Sabbatical leave from the symphony hall all in the space of five years between 1967 University of Auckland, to complete my PhD. -

Welcome to the 2014 Auckland Writers Festival

Prize winning fiction ofAdam Johnson and the hot-off-the-press memoir of CONTENTS WELCOME inner circle defector Jang Jin-sung. 8 What’s On 9 Wednesday 14 May TO THE 2014 Following a year where stories of 9 Thursday 15 May surveillance and gender dominated 10 Friday 16 May the public discourse, writers will 14 Saturday 17 May AUCKLAND debate the merits of privacy and 21 Sunday 18 May deliver a powerhouse discussion 27 Family Day on the position of women. 29 Workshops WRITERS 45 Biographies 74 Index Music’s powers of narration will wow 75 Booking and Festival Information in three special performance events, 77 Booking Form FESTIVAL as well as at a session in memory 81 Timetable of Hello Sailor’s Dave McArtney, chaired by Karyn Hay. The brilliance of Jane Austen will be honoured in the CONTACT DETAILS one woman play Austen’s Women and 58 Surrey Crescent, Suite 3, Level 2, we’ll send 30 strangers out to create Grey Lynn, Auckland 1021, New Zealand tales of the night on a Midnight Run Phone +64 (0)9 376 8074 with performer, poet and playwright Fax +64 (0)9 376 8073 Inua Ellams. THE ONLY PLACE TO BE Email: [email protected] Website: writersfestival.co.nz A WORD FROM THE There are exclusive opportunities FESTIVAL DIRECTOR to be entertained by loved writers FESTIVAL TRUST BOARD Nicky Pellegrino and Sarah-Kate Lynch at Toto; take tea with novelists Carole Beu, Erika Congreve, Owen Marshall, Jenny Pattrick and Nicola Legat, Phillipa Muir, Fiona Kidman or go awol over lunch Mark Russell, Sarah Sandley (Chair), with explorer Huw Lewis-Jones at Delina Shields, Peter Wells, the Langham; and hang out at hot Josephine Green (Ex Officio) Auckland joint Ostro with Michelin- starred chef Josh Emett. -

Connecting, Developing and Designing

Connecting, Developing and Designing 13th - 15th May 2020 Christchurch, New Zealand CONTENTS Sponsors ...................................................................................... 3 Message from the Learning Environments Australasia Chair ....... 5 Message from the co-conveners .................................................. 6 Pre-Conference Event: Queenstown Schools’ LENZ Tour 2020 ...... 7 Programme .................................................................................. 8 Speakers ...................................................................................... 11 re:Activate Sessions ..................................................................... 14 Site Tours ..................................................................................... 20 Social Events ................................................................................ 37 Accommodation ........................................................................... 38 Registration Fees ......................................................................... 39 General Information .................................................................... 40 th May 2020 th - 15 Christchurch 13 SPONSORS PLATINUM SPONSORS GOLD & AWARDS SPONSOR BRONZE SPONSORS COFFEE CART SPONSORS CONFERENCE APP SPONSOR LANYARD & NAME TAG SPONSOR SITE TOUR SPONSOR TRADE DISPLAY SPONSORS 20TH ANNUAL LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS AUSTRALASIA CONFERENCE 3 Creating CO Neutral Learning Environments Designed to refl ect the natural rainforest and jungle habitat of the Orangutan -

NZ Architecture in the 1970S: a One Day Symposium

"all the appearances of being innovative": NZ architecture in the 1970s: a one day symposium Date: Friday 2nd December 2016 Venue: School of Architecture/Te W āhanga Waihanga [please note due to building work, the symposium may be held on the Kelburn campus at VUW, more details closer to the date]. Victoria University/Te Whare W ānanga o te Ūpoko o te Ika a M āui, Wellington Convener: Christine McCarthy ([email protected]) Mike Austin's seemingly faint praise, in a 1974 review of a medium-density housing development, that the architecture had "all the appearances of being innovative," is echoed in Douglas lloyd Jenkins' observation that: "Although the 1970s projected an aura of pioneering individualism, the image disguised a high degree of conformity." The decade's anxious commencement, with the imminent threat of the European Economic Community (EEC) undermining our economic relationship with Mother Britain, was perhaps symptomatic of a risqué appearance being only skin deep. Our historic access to Britain's market to sell butter and cheese was eventually secured in the Luxembourg agreement, which temporarily retained New Zealand trade, but with reducing quotas, as a mechanism to gradually wean New Zealand's financial dependency on exports to Britain. As Smith observes: "Many older better-off Pakeha New Zealanders considered as betrayal Britain's entry in January 1973 to the EEC." The same year we joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). As if in response, in architecture, colonial references were both recouped and abused, though lloyd Jenkins also credits the wider Victorian revival, dating from the mid-1960s, to its co- incidence with "a period in which most New Zealand towns and cities began to celebrate their centenaries." Peter Beaven's Chateau Commodore Hotel (Christchurch, 1972-73), as an example, alluded to Stokesay Castle (Shropshire, 1285) and a thirteenth-century barn (Cherwill, Wiltshire), resulting in a "playful .. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2019 Contents 1 From the Chair 20 Wakefield Fellowship brings hope to sufferers of stroke 2 The Town Hall story A Christchurch dream renewed 22 The UC Māpura Bright Start Scholarship as the spark for future success 4 Rotary Youth Trust Scholarship supports software aspirations 24 Donation supports UC research into nutrition and mental health 6 Prize in legal ethics fosters academic and professional excellence 26 Final-year UC Engineering students get hands-on experience 8 Te Mātāpuna Mātātahi Children’s University opens doors for children and their whānau 28 Astronomy school exceeds students’ expectations 10 Bright ideas spark business success 30 Bequest supports young women to 12 Prominent alumnus supports emerging engineer a career entrepreneurs 32 Thank you to our 2019 donors 14 The University of Canterbury Students’ Association thanks you for Haere-roa 38 Thank you to our 2019 board volunteers 16 Research facilitates positive change from 39 Financial statements 2019 ‘brutal old days’ of rape trials 18 Bequest helps astronomer with stellar research From the Chair Thank you for your philanthropic support of Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha | University of Canterbury (UC) in 2019. Through your significant contributions to UC Tūmahana | University of Canterbury Foundation as alumni, friends and staff, you have helped to strengthen our mission of providing excellence in all aspects of research, teaching and learning. Your support for our students, researchers and the greater UC community shows that you understand the importance of higher education and how education can change lives. Thank you to those of you who have chosen to leave a gift in your Will and whom we have now welcomed into our Partners in Excellence programme. -

The Gift of Imagination Storylines Margaret Mahy Day, 28 March 2009 Heaton Intermediate, Christchurch

ISSN 11750189: Volume 8: Issue 2: May 2009 The Gift of Imagination Storylines Margaret Mahy Day, 28 March 2009 Heaton Intermediate, Christchurch Penny Scown & Diana Murray (Scholastic New Zealand), June Peka, Anna Gowan, & Libby Limbrick; Julie Harper & Robyn Belton; Margaret Mahy, Andrew Crowe & Libby Limbrick Christchurch is the only city in New Zealand to display the Another exciting aspect of this Margaret Mahy Day was busts of two children’s writers. (Three if you count Kipling.) that two major new developments in children’s literature Margaret Mahy’s cheerful representation outside the Arts were unveiled. Centre has a plaque honouring her as ‘Christchurch Joy Cowley Workshop: Joy Cowley has agreed to run a children’s librarian, world-famous writer of magical stories two-day interactive workshop in Christchurch in September and verse for children and young adults, giver of the gift of 2009, as a Storylines fundraising activity. Another imagination’. workshop is planned for Auckland early in 2010. (See page 9 for more information.) Thus it was doubly appropriate that the first Margaret Mahy Storylines Gavin Bishop Award for Picture Book Day to take place in the South Island was held in Illustration: This award has a prize of $1500. The winner Christchurch. In her welcome, Libby Limbrick pointed out will work with Gavin as mentor on illustrations for a 32- several unique features of the day. ‘It confirms Storylines page book which may be published by Random House. as a truly national organisation,’ said Libby, adding, ‘It is (More information is on page 10.) also marvellous to hold it in Margaret Mahy’s territory.’ She thanked Te Tai Tamariki Aotearoa New Zealand Children’s The raffle of a framed original Gavin Bishop illustration was Literature Trust for their help with the Margaret Mahy Day’s won by Heather Manning, from Palmerston North.