The Bad Seed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Till Death Do Us Part: a Study of Spouse Murder GEORGE W

Till Death Do Us Part: A Study of Spouse Murder GEORGE W. BARNARD, MD HERNAN VERA, PHD MARIA I. VERA, MSW GUSTAVE NEWMAN, MD Killers of members of their own families have long fueled the archetypical imagination. Our myths, literature, and popular arts are full of such charac ters as Cain, Oedipus, Medea, Othello, Hamlet, and Bluebeard. In our time the murderous children of movies like "The Bad Seed" and "The Omen"; the homicidal father of "The Shining"; the killer spouses of Hitchcock's "Midnight Lace" and "The Postman Always Rings Twice" bespeak a continuing fascination with the topic. In contrast, until recently the human sciences paid" selective inattention" I to the topic of family violence. Only in the past decade has violence in the family become "a high priority social issue,"~ an "urgent situation, ":1 on which privileged research energy needs to be expended. We deal here with the murder of one spouse by the other, a topic on which research remains sparse4 despite the growing interest in family vio lence. Based on data derived from twenty-three males and eleven females accused of such crime, we contrast and compare the two groups attempting to identify common and gender-related characteristics in the offense, the relationship between murderer and victim, as well as the judicial disposition of the accused. The importance of the doer-sufferer relation in acts of family criminal violence has been well established. In major sociological studies"-s it has been found that about one out of five (or nearly one out of four) deaths by murder in the U.S. -

William March (William Edward Campbell)

William March (William Edward Campbell) William March (1893-1954) was a decorated combat veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps in the First World War, a successful businessman, and an influential author of numerous novels and short stories. His literary work draws primarily on two sources: his childhood and youth in Alabama and his war experiences in France. Four of March’s six novels are set in Alabama, as are most of his short stories. March’s Alabama-based works are commonly referred to as the “Pearl County” or “Reedyville” series, after the fictional Alabama locales in which many of them are set. March was born William Edward Campbell on September 18, 1893, in Mobile, Mobile County. March was the second of 11 children born to John Leonard Campbell, an orphaned son of a Confederate soldier and itinerant worker in the lumber towns of south Alabama and the Florida panhandle, and Susan March Campbell, daughter of a well-to- do Mobile family. The Campbells, however, were poor, so William left school at the age of 14 to work in the office of a lumber mill in Lockhart, Covington County. At the age of 16, he moved to Mobile, where he took a job in a law office to earn money for school. He spent a year obtaining his high school diploma at Valparaiso University in Indiana and then studied law for a year at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County. He moved to New York City in 1916 and settled in Brooklyn, taking a job as a clerk with a New York law firm. -

When Victims Become Perpetrators

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2005 The "Monster" in All of Us: When Victims Become Perpetrators Abbe Smith Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/219 38 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 367-394 (2005) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications February 2010 The "Monster" in All of Us: When Victims Become Perpetrators 38 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 367-394 (2005) Abbe Smith Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/219/ Posted with permission of the author The "Monster" in all of Us: When Victims Become Perpetrators Abbe Smitht Copyright © 2005 Abbe Smith I and the public know What all school children learn, Those to whom evil is done Do evil in return. 1 I. INTRODUCTION At the end of Katherine Hepburn's closing argument on behalf of a woman charged with trying to kill her philandering husband in the 1949 film Adam's Rib,2 Hepburn tells the jury about an ancient South American civilization in which the men, "made weak and puny by years of subservience," are ruled by women. She offers this anthropological anecdote in order to move the jury to understand why a woman, whose "natural" feminine constitution should render her incapable of murder,3 might tum to violence. -

Or a Bad Seed?

Good vs. Bad Everyone has good moments, like cheering up a sad friend, but they also have bad moments too, like fighting with a sibling. Draw a picture of yourself being a Good Egg in the left column and a picture of yourself being a Bad Seed in the right column. GOOD BAD www.harpercollinschildrens.com Art copyright © 2019 Pete Oswald. Permission to reproduce and distribute this page has been granted by the copyright holder, HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. A Helping Hand The bad seed says he wasn’t always a bad seed. How do you think he felt when he heard others call him a “bad seed”? How could the others have helped him instead? Draw a picture of what you would have done to help the bad seed. www.harpercollinschildrens.com Art copyright © 2019 Pete Oswald. Permission to reproduce and distribute this page has been granted by the copyright holder, HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. Five Ways to Be a Good Egg At the beginning of the story, the Good Egg shows how good he is by helping carry groceries, getting a cat down from a tree, and even painting a house. In the boxes below, draw five ways you can be a good egg too! www.harpercollinschildrens.com Art copyright © 2019 Pete Oswald. Permission to reproduce and distribute this page has been granted by the copyright holder, HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. Eggs to Crack You Up Along with the Good Egg, the other eggs make a great bunch. All of them are silly and funny in their own ways, and they have the best faces. -

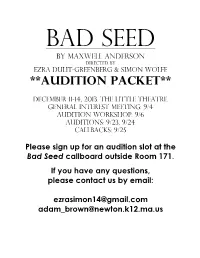

Audition Packet**

Bad Seed By Maxwell Anderson Directed by Ezra Dulit-Greenberg & Simon wolfe **Audition packet** DECEMBER 11-14, 2013. The Little Theatre. General Interest Meeting: 9/4 Audition Workshop: 9/6 Auditions: 9/23, 9/24 Callbacks: 9/25 Please sign up for an audition slot at the Bad Seed callboard outside Room 171. If you have any questions, please contact us by email: [email protected] [email protected] Information Please sign up for one audition slot on the callboard outside Room 171 and pick up a script. You are required to read Bad Seed prior to your audition. Please fill out this packet and give it to a stage manager at your audition. Please prepare and memorize one of the monologues of your gender in this packet, and do the same for an additional monologue that is not from Bad Seed. Please have the second monologue you choose contrast with your choice from the packet. This means that it should highlight different emotions, intentions, and styles that show your acting range. In other words: if one monologue is dramatic, the other should be comedic. You will be asked to present both monologues. If you need any help finding a monologue, please ask or email Mr. Brown or us for help – we will be glad to provide it. If you would like to work on your audition, feel free to contact Mr. Brown or another student director. [email protected], [email protected] We are looking for actors with strong fundamentals (vocal energy, movement with purpose, etc.), honesty, and intention. -

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for Your Wife

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for your Wife by Ray Cooney presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French 9 to 5, The Musical by Dolly Parton presented by special arrangement with MTI Elf by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin presented by special arrangement with MTI 4 Weddings and an Elvis by Nancy Frick presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French The Cemetery Club by Ivan Menchell presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks presented by special arrangement with MTI An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Newsies by Harvey Fierstein presented by special arrangement with MTI _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2019-2020 Season A Comedy of Tenors – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Mamma Mia – presented by special arrangement with MTI The Game’s Afoot – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French The Marvelous Wonderettes – by Roger Bean presented by special arrangement with StageRights, Inc. Noises Off – by Michael Frayn presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Cabaret – by Joe Masteroff presented by special arrangement with Tams-Witmark Barefoot in the Park – by Neil Simon presented by special arrangement with Samuel French (cancelled due to COVID 19) West Side Story – by Jerome Robbins presented by special arrangement with MTI (cancelled due to COVID 19) 2018-2019 Season The Man Who Came To Dinner – by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Mary Poppins - Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. -

The Bad Seed Audition Information Packet Ages 13-19

The Bad Seed Audition Information Packet Ages 13-19 The Beverly Art Center’s Spring drama is The Bad Seed. The show is a psycho-drama about a young girl who has inherited the instinct to be a serial killer About the Casting Process An audition is required to participate in the program. Please call 773.445.3838 x216 to reserve an audition slot. Auditions will be held: Monday, March 23, 5:00 to 7:00pm • Audition slots will be 5 minutes in length. • Audition Sides are included at the end of this information packet. We ask that students be prepared to perform the scene in the sides provided (we will provide someone to read with you). • Please take a look at the rehearsal, tech, and performance schedule on Page 2 and come to the auditions prepared to note any conflicts on your audition sheet. Callbacks will be held: Wednesday, March 25, 5:00 to 7:00pm Please Note: We call back about half of the actors who will be cast. If you are not invited to callbacks, you may still have a role in the production! The Cast List will be sent out via e-mail and posted on the BAC School of Theater Callboard by Noon on Saturday, March 28. Casting Policy: • The Bad Seed has a cast of 12 characters, and all teen ages are eligible to audition for any of the roles available. • Those actors that best fit the role will be cast. • Conflicts with scheduled rehearsals must be presented at auditions and may be a factor when casting. -

Dramaturgical Notes

InDepth Notes on She-Rantulas from Outer Space-in 3D! Conceived and Written by Phil Johnson & Ruff Yeager Diversionary Theatre October 2013 Notes written and compiled by Anthony Methvin Literary Associate at Diversionary Theatre Table of Contents A Letter From Our Writer / Director by Ruff Yeager ........................................ 3 She-Rantulas from Outer Space Creator Biographies ...................................... 4 Conquering She-Rantulas: A Glossary of Influences ......................................... 5 “Camping It Up With The Bad Seed” by Michael Bronski .............................. 12 A Legacy of New Works at Diversionary Theatre ........................................... 17 2 A Letter From Our Writer / Director In 2009, we had the idea to present The Bad Seed as a satire on the fear of the 'other' in our contemporary society - particularly the 'gay other'. To accomplish that task, I suggested that men play the women's roles and vice- versa. Phil loved the idea. I adapted Maxwell Anderson's play and we presented our concept as a staged reading in February of 2010. Those who came really had a great time. The room was filled with laughter and applause. The timing, however, wasn't right for Diversionary to stage a production then. About one year later John Alexander became the new Executive Artistic director of the theatre. Phil and I approached him with the property and he was eager to see Diversionary produce it. As John endeavored to find a slot for the show in the season he discovered that the rights were not available if we wanted to switch the gender roles. A series of spectacular events then occurred (as they often do in the theatre) that allowed Phil and I to write our own comic play based on the idea of fear of the 'other'. -

The Freudian Slip

CSB/SJU PSYCHOLOGY DEPARTMENT PRESENTS THE FREUDIAN SLIP Sigmund Freud VOLUME XII, ISSUE 2 NOVEMBER 2013 SIGMUND F REUD, (193 8) NATURE VS. NURTURE COMES TO LIFE IN THE BAD SEED BY TAYLOR PEDERSON are circumstantial. The inter- The Bad Seed, a 1950’s play had anything to do with the iors. Christine’s father disa- play of nature and nurture is by Maxwell Anderson based boy drowning. Christine grees and believes that crimi- ever changing depending on off of William March’s nov- questions how her daughter nals are truly a product of a the genetic and environmental el, was put on by the Thea- Rhoda could be capable of bad environment. So which contexts for each individual. ter Department this fall. such horrific actions when is true? Are criminals a prod- For one individual, genetics The mysterious and eerie she had been brought up in uct of their environment? may be the most prominent plot captivated the audience a normal A l t e r n a - factor influencing antisocial environ- tively, are while the mystery unrav- behaviors, while for another eled. The underlying theme m e n t . “There are bad seeds– there bio- individual, environmental fac- in the story contained a T h i s l o g i c a l just plain bad from tors may be most prominent. psychological basis in the question e x p l a n a - the beginning, and As for Rhoda’s case, she was debate of nature vs. nur- is at the tions for raised in a nearly perfect envi- ture. -

Recall Roster by D.A. Boxwell Recalling Forgotten, Neglected, Underrated, Or Unjustly Out-Of-Print Works

Recall Roster by D.A. Boxwell Recalling forgotten, neglected, underrated, or unjustly out-of-print works William March. Company K. Intro. By Philip D. Beidler. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989. hen William March’s novel was first published in January 1933, its author happened to be in Hamburg , Germany. A former Marine who was wounded at Belleau WoodW and on the Blanc Mont Ridge, March was the E u ropean re p resentative of the Wa t e rman Steamship Corporation. Witnessing the rise of Hitler to power during his stay in Europe, March got ironic confirmation of what the unsympathetic character, the Judge Advocate Lt. James Fairbrother says at the end of novel, when he rants against pacifism in a windy political speech: “‘Brotherhood of man,’ indeed—I’d laugh if the situation were not so fraught with danger.— Germany is not to be ignored, either.—How shortsighted we were to let them get on their feet again.—” (255). Company K, March’s first novel, is a masterful reflection of how much the futility and carnage of World War I festered in people’s hearts and souls and made the Second World War a seeming inevitability. Coming as it did at the end of a vogue for Great War fiction in the late 20s and early 30s, Company K is, in many ways, the pure distillation, in literary fiction, of the bitter disillusionment spawned by the Great War, and the war’s seeming inconclusiveness. But even more signifi- cant, and less predictable, Company K is neatly metafictional that makes it a harbinger of much post-Vietnam writing. -

Sunflower July 13, 1967

Summer Theatre Will Present THE Kansan's Comedy 'Bus Stop' Summer Theatre will present trying to get "Cherie" to marry of upstage, downstage and about SUNFLOWER ''Bus Stop," a play set in Kan him. He had to learn to vault entrances and exits. sas and written by William Ing~ the lunch counter and had some difficulty in learning to whistle The major costuming problem a Kansas pla.ywright, in Wilner VOL. LXXI NO. 64 WICHITA STATE UNIVER5ITY JULY 13, 1967 Auditorium at 8 p.m. Thursday, with two fingers in his mouth. has been finding a size 48 bus 1 Friday and Saturday. _, Kovacs came to the United States driver's uniform. The bus com at theend ofWorld War II from panies of Wichita have looked, The plot deals with a bus Holland. Terry is excited about but they haven'tbeenabletocome stranded somewhere between To the part of ' 'Bo Decker" since up with one.Presentlyanairforce Annual Band Concert peka and Kansas City during a he knows Inge and he said that uniform is being adapted. March blizz.ard. The passengers Terry should play the part of •'Bo" sometime. Most of tht: cast are students, on the bus are thrown together with the exception of Washburn Scheduled For Monday in a small restaurant, the ''Bus who is an East High drama in Stop." As Kovacs' sidekick, Knetsch structor and Calhoun who is a The annual WSU Band Con concert, the Colas Breugnan has had to learn to play "Red member of the WSU English fa cert will be held Monday.