Dramaturgical Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![1939-01-25 [P A-8]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6538/1939-01-25-p-a-8-2056538.webp)

1939-01-25 [P A-8]

technicolor: 12:10, 2:30, 4:50, 7:10 AMUSEMENTS._ Mr. Hitchcock Proves In a New British Where and When and 9:30 pm. Really Mystery Little—“100 Men and a Girl,” Deanna Durbin sings, Leopold Sto- Current Theater Attractions a kowski conducts the orchestra: 11 Film Director’s Medium and Time of Showing a.m., 12:45, 2:35, 4:20, 6:05, 7:45 and 'NIGHT AT 8:S0 9:40 p.m. The troly Joyous comedy hy and from Ian Hay’s nerul “The Henoemaater" ‘The National—“Bachelor Born," Ian BeUsco—“Beethoven Concerto,” Lady Vanishes’ Is Case in Point; Hay’s hit comedy of school life: new film with much of the master’s 2:30 and 8:30 music: 8:10 and 9:50 BACHELOR BORN Picture Also Introduces New p.m. 4:50, 6:20, pm. Capitol—"Stand Up and Fight,” Trans-Lux—News and shorts; con- It’s a wow!—WaHar Wlneholl Bob Taylor helps railroads battle tinuous from 10 am. Eyes.. 05c. (1.10, fl.SS, *2.20 Recruit for Wed-Sat. Mats., fide, Sl.IO. Sl.U English Hollywood stage coaches: 10:30 am., 1:20, 4:10, By JAY CARMODY. 7:05 and 9:55 p.m. Stage shows: 12:30, 3:20, 6:10 and 9:05 pm. School NATIONAL—This One of the things they insist upon in Hollywood is that the motion Play Tryouts Thursday The of picture is a director’s medium, something for which one cannot blame Earle—“Zaza," Claudette Colbert Players’ Club the Central 4 O'Clock the actor and the writer. -

Autograph Albums - ITEM 936

Autograph Albums - ITEM 936 A Jess Barker Jocelyn Brando Lex Barker Marlon Brando Walter Abel Binnie Barnes Keefe Brasselle Ronald Adam Lita Baron Rossano Brazzi Julie Adams Gene Barry Teresa Brewer (2) Nick Adams John Barrymore, Jr. (2) Lloyd Bridges Dawn Addams James Barton Don Briggs Brian Aherne Count Basie Barbara Britton Eddie Albert Tony Bavaar Geraldine Brooks Frank Albertson Ann Baxter Joe E. Brown Lola Albright John Beal Johnny Mack Brown Ben Alexander Ed Begley, Sr. Les Brown John Alexander Barbara Bel Geddes Vanessa Brown Richard Allan Harry Belafonte Carol Bruce Louise Allbritton Ralph Bellamy Yul Brynner Bob “Tex” Allen Constance Bennett Billie Burke June Allyson Joan Bennett George Burns and Gracie Allen Kirk Alyn Gertrude Berg Richard Burton Don Ameche Polly Bergen Spring Byington Laurie Anders Jacques Bergerac Judith Anderson Yogi Berra C Mary Anderson Edna Best Susan Cabot Warner Anderson (2) Valerie Bettis Sid Caesar Keith Andes Vivian Blaine James Cagney Dana Andrews Betsy Blair Rory Calhoun (2) Glenn Andrews Janet Blair Corinne Calvet Pier Angeli Joan Blondell William Campbell Eve Arden Claire Bloom Judy Canova Desi Arnaz Ben Blue Macdonald Carey Edward Arnold Ann Blyth Kitty Carlisle Mary Astor Humphrey Bogart Richard Carlson Jean-Pierre Aumont Ray Bolger Hoagy Carmichael Lew Ayres Ward Bond Leslie Caron B Beulah Bondi John Carradine Richard Boone Madeleine Carroll Lauren Bacall Shirley Booth Nancy Carroll Buddy Baer Ernest Borgnine Jack Carson (2) Fay Bainter Lucia Bose Jeannie Carson Suzan Ball Long Lee Bowman -

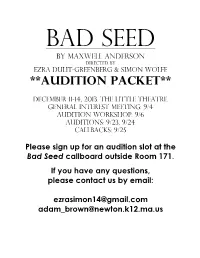

Audition Packet**

Bad Seed By Maxwell Anderson Directed by Ezra Dulit-Greenberg & Simon wolfe **Audition packet** DECEMBER 11-14, 2013. The Little Theatre. General Interest Meeting: 9/4 Audition Workshop: 9/6 Auditions: 9/23, 9/24 Callbacks: 9/25 Please sign up for an audition slot at the Bad Seed callboard outside Room 171. If you have any questions, please contact us by email: [email protected] [email protected] Information Please sign up for one audition slot on the callboard outside Room 171 and pick up a script. You are required to read Bad Seed prior to your audition. Please fill out this packet and give it to a stage manager at your audition. Please prepare and memorize one of the monologues of your gender in this packet, and do the same for an additional monologue that is not from Bad Seed. Please have the second monologue you choose contrast with your choice from the packet. This means that it should highlight different emotions, intentions, and styles that show your acting range. In other words: if one monologue is dramatic, the other should be comedic. You will be asked to present both monologues. If you need any help finding a monologue, please ask or email Mr. Brown or us for help – we will be glad to provide it. If you would like to work on your audition, feel free to contact Mr. Brown or another student director. [email protected], [email protected] We are looking for actors with strong fundamentals (vocal energy, movement with purpose, etc.), honesty, and intention. -

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for Your Wife

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for your Wife by Ray Cooney presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French 9 to 5, The Musical by Dolly Parton presented by special arrangement with MTI Elf by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin presented by special arrangement with MTI 4 Weddings and an Elvis by Nancy Frick presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French The Cemetery Club by Ivan Menchell presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks presented by special arrangement with MTI An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Newsies by Harvey Fierstein presented by special arrangement with MTI _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2019-2020 Season A Comedy of Tenors – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Mamma Mia – presented by special arrangement with MTI The Game’s Afoot – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French The Marvelous Wonderettes – by Roger Bean presented by special arrangement with StageRights, Inc. Noises Off – by Michael Frayn presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Cabaret – by Joe Masteroff presented by special arrangement with Tams-Witmark Barefoot in the Park – by Neil Simon presented by special arrangement with Samuel French (cancelled due to COVID 19) West Side Story – by Jerome Robbins presented by special arrangement with MTI (cancelled due to COVID 19) 2018-2019 Season The Man Who Came To Dinner – by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Mary Poppins - Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H. -

Bad Seed by William March

Bad Seed By William March If searching for the book by William March Bad Seed in pdf form, then you have come on to the faithful website. We present complete version of this book in ePub, DjVu, PDF, doc, txt formats. You can reading by William March online Bad Seed or download. In addition to this book, on our website you can read the guides and different artistic books online, or load them as well. We wish invite regard what our site does not store the book itself, but we give ref to the website wherever you can load either reading online. If you need to download Bad Seed by William March pdf, then you've come to the right site. We own Bad Seed ePub, doc, DjVu, txt, PDF forms. We will be pleased if you return to us afresh. 0553197940 - The Bad Seed by William March - The Bad Seed by William March and a great selection of similar Used, New and Collectible Books available now at AbeBooks.com. The Bad Seed book | 6 available editions | Alibris The Bad Seed by William March starting at $0.99. The Bad Seed has 6 available editions to buy at Alibris The Bad Seed: William March: 9780060795481: - The Bad Seed (William March) at Booksamillion.com. Now reissued - William March's 1954 classic thriller that's as chilling, intelligent and timely as ever before. The Bad Seed by William March - AbeBooks The Bad Seed by William March and a great selection of similar Used, New and Collectible Books available now at AbeBooks.com. -

Staats Dissertation

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Don’t Look Now: The Child in Horror Cinema and Media A Dissertation Presented by Hans Staats to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University August 2016 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Hans Staats We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Krin Gabbard – Dissertation Co-Advisor Professor Emeritus, Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature Stony Brook University E. Ann Kaplan – Dissertation Co-Advisor Distinguished Professor of English and Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature Stony Brook University Jacqueline Reich – Chairperson of Defense Professor and Chair, Department of Communication and Media Studies Fordham University Christopher Sharrett – Outside Member Professor, College of Communication and the Arts Seton Hall University Adam Lowenstein – Outside Member Associate Professor of English and Film Studies University of Pittsburgh This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Don’t Look Now: The Child in Horror Cinema and Media by Hans Staats Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University 2016 This dissertation examines the definition of the monstrous child in horror cinema and media. Spanning from 1955 to 2009 and beyond, the question of what counts as a monstrous child illuminates a perennial cinematic preoccupation with monstrosity and the relation between the normal and the pathological. -

![1939-01-20 [P A-12]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5701/1939-01-20-p-a-12-5495701.webp)

1939-01-20 [P A-12]

bratlon guests. Miss De Havllland, AMUSEMENTS. Three on a Hit Annabella, George Brent, Paul Tale Is Told Whiteman and Jean Hersholt have HELD OVER Romeo-Juliet Broadway Errol AGAIN! Flynn been announced previously. Others Again in Palace Film Here will be announced shortly. Coming Wlnatr of National _AMUSEMENTS._ Board of Rtvlow Award at THE BEST FILM OF THE YEAR at Has Pictorial Ciat. from 4 P. M„ 15. to * ‘Kentucky,’ Palace, whl,« For Ball PEI ACPI) °PP- Boat* Excellence Beyond Average Picture PtimtU V.tlonnl 0149 Warners’ Star Which Features Technicolor Constitution Boll. Next Son. Alt..« PJf. Is Latest YEHUDI By JAY CARMODY. After Cinderella among Hollywood’s favorite tales Is the story of On List “Romeo and Juliet.” A good yarn it is, too, which undoubtedly is the in- MENUHIN spiration behind its revival by Twentieth Century-Fox under the title Errol Flynn, Warner Bros, star, Victoria Resina Worli-Fomons Violinist—In Beeltal Only tS.SO Scats Available Bvenlncs* ■ooU *2.20, *2.75—Mrs. Dorsey’s. U00 O “Kentucky” at the Palace. Told in color this time, plus a background will come to Washington for the Mats. Today A Sat. at *:SO Sharp! of the Kentucky Derby, the old story has a pictorial loveliness which may President's birthday celebration, ac- make that it is a very hard to streamline even with such to from John J. you forget thing cording word Pay- BEG. NEXT MON. EVE. AT S:30 •f—- stars as Loretta Young and Richard" ette, Warners’ general zone mana- The truly Joroua comedy by bad from Greene. -

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Fall

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont Fall 2004 All About Eve Eve Ann Baxter Fall 2006 Almost Famous Penny Lane Kate Hudson Fall 2004 Along Came Polly Reuben Feffer Ben Stiller Fall 2005 Along Came Polly Polly Prince Jennifer Aniston Fall 2004 Amelie Amélie Poulain Audrey Tautou Fall 2000 American Beauty Lester Burham Kevin Spacey Fall 2004 American Beauty Angela Hayes Mena Suvari Fall 2006 American History X Danny Edward Furlong Spring -

The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema Ghosts of Futurity at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century jessica balanzategui The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema Ghosts of Futurity at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century Jessica Balanzategui Amsterdam University Press Excerpts from the conclusion previously appeared in Terrifying Texts: Essays on Books of Good and Evil in Horror Cinema © 2018 Edited by Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. Excerpts from Chapter Four previously appeared in Monstrous Children and Childish Monsters: Essays on Cinema’s Holy Terrors © 2015 Edited by Markus P.J. Bohlmann and Sean Moreland by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson NC 28640. Cover illustration: Sophia Parsons Cope, 2017 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 651 0 e-isbn 978 90 4853 779 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462986510 nur 670 © J. Balanzategui / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 9 The Child as Uncanny Other Section One Secrets and Hieroglyphs: The Uncanny Child in American Horror Film 1. -

Remington Steele Episo De Guide

Remington Steele Episo de Guide Version Compiled by Raymond Chen Revision history Version Septemb er Version Version Version Version x February internal Version Decemb er c Copyright Raymond Chen all rights reserved Permission is granted to copy and repro duce this do cument provided that it b e distributed in its entirety including this page No charge may b e made for this do cument b eyond the costs of printing and distribution No mo dications may b e made to this do cument Preface This episo de guide b egan as a collection of private notes on the program Remington Steele which I had kept while watching the show on NBC in the eighties Yes I take notes on most television programs I watch Call me analretentive Sometime in early I got the crazy idea of creating an episo de guide and the rst edition of this guide eventually app eared later that year Still not satised and unable to recall the plots of most of the episo des b eyond the sketchiest of descriptions I decided to give my feeble brain cells a breather and write out more detailed plot summaries as I watched the episo des I consider using a VCR to b e cheating and b esides you can read a plot summary faster than you can watch a tap e There you have it the confessions of a neurotic televisionwatcher Not in the printed guide but available in the guide source is a summary of musical themes and a list of quotes Remington Steele still gets my vote for the show with the b est incidental music No other show I know comes even close The quotes you can add to your favorite -

Year Date Name of Production Description 1917 September 27, 28, 28 Have a Heart a Musical Comedy by Guy Bolton and P. G

Year Date Name of Production Description 1917 September 27, 28, 28 Have A Heart A musical comedy by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, music by Jerome Kern 1917 1-Oct Furs and Frills A musical with lyrics by Edward Clark, music by Silvo Hein 1919 6-Oct The Gallo Opera Co. A revival of William S. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan's The Mikado , music directed by Max Bendix 1922 May 19 and 20 Dulcy A comedy in three acts by George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly 1924 9-Apr Anna Pavlowa A ballet featuring Hilda Butsova and Corps De Ballet; Ivan Clustine, Balletmaster and conductor Theodore Stier 1924 April 10, 11, 12 Jane Cowl Portraying Juliet in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet ; staged by Frank Reicher 1927 1-Sep My Princess A modern Operetta based on a play by Edward A. Sheldon and Dorothy Donnelly; music by Sigmund Romberg 1927 September 5, 6, 7 Creoles A romantic comedy drama by Samuel Shipman and Kenneth Perkins 1927 September 8, 9, 10 The Cradle Song A Comedy in two acts by Gregario and Maria Martinez Sierra translated in English by John Garrett Underhill 1928 January 26, 27, 28 Quicksand A play presented by Anna Held Jr. and written by Warren F. Lawrence 1928 January 30 Scandals A play based on the book by Williams K. Wells and George White 1928 September 17, 18, 19 Paris Bound/Little Accident A comedy by Philip Barry presented by Arthur Hopkins; featuring (1 play per side of one Madge Kennedy sheet) 1928 September 20, 21, 22 Little Accident/Paris Bound A comedy in three acts by Floyd Dell and Thomas Mitchell; staged (1 play per side of one by Arthur Hurley sheet) 1928 October 1, 2, 3, The Shanghai Gesture/The presented by A.