Covering the Witches in Arthur Miller's the Crucible: a Feminist Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

295 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-74538-3 - The Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller, Second Edition Edited by Christopher Bigsby Index More information INDEX Aarnes, William 281 Miller on 6, 152, 161 Abbott, Anthony S. 279 and No Villain/They Too Arise 6, 25, 28 “About Theatre Language” 76 productions xiii, 159, 161, 162 Ackroyd, Peter 166–67 revisions 160, 161 Actors’ Studio 220, 226 American Legion 215 Adding Machine, The 75 Anastasia, Albert 105 Adler, Thomas P. 84n, 280, 284 Anastasia, Tony 105, 108n Adorno, Theodor 201 Anderson, Maxwell 42 After the Fall xii, xiii, 4, 8, 38, 59–60, 61, Angel Face 209 118, 120–26, 133, 139, 178, 186, 262, Another Part of the Forest 285 265, 266 Anthony Adverse 216 changing critical reception 269–70 Antler, Joyce 290 The Last Yankee and 178 Archbishop’s Ceiling, The 5–6, 8, 141, Miller on 54–55, 121–22, 124, 126, 265 145–51, 167, 168 productions xii, xiii, 121, 123, 124–25, Miller on 147, 148, 152 156–57, 270, 283 productions xiii, 159, 161–62 The Ride Down Mount Morgan and 173 revisions 141, 159, 161, 162n structure 7, 128 Aristotle 13, 64, 234, 264 studies of 282, 284–85, 288, 290, 293 Aronson, Boris 129 viewed as autobiographical/concerned Art of the Novel, The 237n with Monroe 4, 121, 154, 157, 195, Arthur Miller Centre for American Studies 269, 275 (UEA) xiv, xv, 162 Ajax 13 Arthur Miller Theatre, University of Albee, Edward 154 Michigan xv Alexander, Jane 165 Aspects of the Novel 235 All My Sons xi, 2, 4, 36–37, 47, 51–62, 111, Asphalt Jungle, The 223 137, 209, 216, 240, 246, 265 Assistant, The 245 film versions xiv, 157–58, 206–12, 220, Atkinson, Brooks 293 232 Auden, W. -

Biblioteques De L'hospitalet

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA April 16, 2020 All My Sons Arthur Miller « The success of a play, especially one's first success, is somewhat like pushing against a door which suddenly opens from the other side. One may fall on one's face or not, but certainly a new room is opened that was always securely shut until then. For myself, the experience was invigorating. It made it possible to dream of daring more and risking more. The audience sat in silence before the unwinding of All My Sons and gasped when they should have, and I tasted that power which is reserved, I imagine, for Contents: playwrights, which is to know that by one's invention Introduction 1 a mass of strangers has been publicly transfixed. Author biography 2-3 Arthur Miller All My Sons - 4 Introduction & Context All My Sons - 5-6 » Themes Notes 7 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_My_Sons] Page 2 Author biography Arthur Miller is considered Street Crash of 1929, and had to Willy Loman, an aging Brooklyn one of the greatest American move from Manhattan to salesman whose career is in playwrights of the 20th Flatbush, Brooklyn. After decline and who finds the values century. His best-known plays graduating high school, Miller that he so doggedly pursued have include 'All My Sons,' 'The worked a few odd jobs to save become his undoing. Crucible' and the Pulitzer enough money to attend the Prize-winning 'Death of a University of Michigan. While in Salesman won Miller the highest Salesman.' college, he wrote for the student accolades in the theater world: paper and completed his first the Pulitzer Prize, the New York Who Was Arthur Miller? play, No Villain, for which he won Drama Critics' Circle Award and the school's Avery Hopwood the Tony for Best Play. -

All My Sons As Precursor in Arthur Miller's Dramatic World

All My Sons as Precursor in Arthur Miller’s Dramatic World Masahiro OIKAWA※ Abstract Since its first production in 1947, Arthur Miller’s All My Sons has been performed and appreciated worldwide. In academic studies on Miller, it secures an important place as a precursor, because it has encompassed such themes as father-son conflict, pursuit of success dream in the form of a traditional tragedy as well as a family and a social play. As for techniques, to begin with, the Ibsenite method of dramatization of the present critical situation and presentation of the past “with sentimentality” are obvious. Secondly, the biblical tale of Cain and Abel from the Old Testament allows the play to disguise itself as a modern morality play on “brotherly love.” Thirdly, Oedipus’s murder of his father in Oedipus Rex is used symbolically to place the play in the Western tradition of drama. Taking all these major themes and techniques into account, the paper argues that the play is dramatizing the universal, and that by looking at the conflict between father and son, we can understand why Miller’s message in All My Sons is significant for Japanese andiences. I. Introducion Most of the reviews appearing in the major newspapers and magazines on All My Sons (1947) were rather favorable, which is quite understandable considering that the play vividly depicts the psychological aspects of the United States during and immediately after the Second World War in a realistic setting. In fact, it is impossible to understand the problems Joe and Chris Keller, the father and the son, get involved in without the background of the war. -

International Research Journal of Commerce, Arts and Science Issn 2319 – 9202

INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF COMMERCE, ARTS AND SCIENCE ISSN 2319 – 9202 An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust WWW.CASIRJ.COM www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions CASIRJ Volume 9 Issue 2 [Year - 2018] ISSN 2319 – 9202 Reflection of a new society in the works of Arthur Miller Ojasavi Research Scholar Singhania University,Pacheri, Jhunjhunu Analysis of writings of Arthur Asher Miller is one of the land mark in English literature. It not only increase the analytical capacity of a scholar but add some information in existing literature which increase the curiosity of the reader in concerned subject and leads to origin of new ideas. The present research concentrates on critical analysis of selected writings of Arthur Asher Miller with emphasis on circumstances under which ideas came in the mind. Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist, and prominent figure in twentieth-century American theatre. Among his most popular plays are All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953) and A View from the Bridge (1955, revised 1956). He also wrote several screenplays and was most noted for his work on The Misfits (1961). The drama Death of a Salesman is often numbered on the short list of finest American plays in the 20th century alongside Long Day's Journey into Night and A Streetcar Named Desire. Before proceeding forward about writings of Miller it is necessary to know about his life and society when he came in to public eye, particularly during the late 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s. -

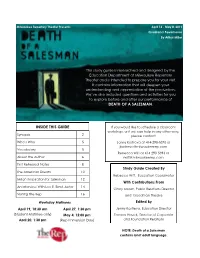

Death of a Salesman. Inside This Guide

Milwaukee Repertory Theater Presents April 12 - May 8, 2011 Quadracci Powerhouse By Arthur Miller This study guide is researched and designed by the Education Department at Milwaukee Repertory Theater and is intended to prepare you for your visit. It contains information that will deepen your understanding and appreciation of the production. We‘ve also included questions and activities for you to explore before and after our performance of DEATH OF A SALESMAN. INSIDE THIS GUIDE If you would like to schedule a classroom workshop, or if we can help in any other way, Synopsis 2 please contact Who‘s Who 5 Jenny Kostreva at 414-290-5370 or [email protected] Vocabulary 5 Rebecca Witt at 414-290-5393 or About the Author 6 [email protected] First Rehearsal Notes 8 Study Guide Created By The American Dream 10 Rebecca Witt, Education Coordinator Miller‘s Inspiration for Salesman 12 With Contributions From An Interview With Lee E. Ernst, Actor 14 Cindy Moran, Public Relations Director Visiting The Rep 16 and Goodman Theatre Weekday Matinees Edited By April 19, 10:30 am April 27, 1:30 pm Jenny Kostreva, Education Director (Student Matinee only) May 4, 12:00 pm Tamara Hauck, Director of Corporate April 20, 1:30 pm (Rep Immersion Day) and Foundation Relations NOTE: Death of a Salesman contains brief adult language. Page 2 SYNOPSIS *Spoiler Alert: This synopsis contains crucial plot because Biff is well-liked and Bernard is not. points. After Bernard leaves, Willy and Linda discuss how much Willy made from sales. They realize All Costume Renderings were drawn by Rachel that it‘s not quite enough to pay the bills, but Healy, Costume Designer. -

Arthur Miller Roxbury, Connecticut, Which Would Become His Long Time Home

Guild's National Award. During 1944 Miller toured army camps to collect background material for his 1945 screenplay, The Story of GI Joe. In 1947 Miller's Name play, All My Sons, was produced and won the New York Critics' Circle Award and two Tony Awards. As his success continued, Miller made the decision in 1948 to build a studio in Arthur Miller Roxbury, Connecticut, which would become his long time home. It was in this studio where he wrote the play that brought him international fame, Death of a By Jamie Kee Salesman. This play was considered a major achievement and has become a classic in American and world theatre. On February 10, 1949, the play premiered on Broadway at the Morosco Theatre. Miller's Death of a Salesman won a Tony Born on October 17, 1915, American playwright Award for best play, the New York City Drama Circle Critics' Award, and the Arthur Miller was a major figure in the American Pulitzer Prize for drama. This was the first time a play won all three of these major theatre and cinema. He was best known for his play, awards. Death of a Salesman, and for his marriage to actress Marilyn Monroe. Miller wrote other plays such as During the 1950s the United States Congress began investigating Communist The Crucible, A View from the Bridge, and All My influence in the arts. Miller compared these investigations to the witch trials of Sons, all of which are still performed and studied 1692, so he traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, to do research. -

THE CRUCIBLE | EDUCATION PACK 1 Arthur Miller – His Life and Times

By Arthur Miller A Bristol Old Vic Production Directed by Tom Morris “The theater is so endlessly fascinating because it’s so accidental. It’s so much like life.” Arthur Miller, The New York Times (9 May 1984) Education Pack Introduction As a teacher I have always loved using The Crucible as Contents a text with young people. It has a depth and resonance which allows us to challenge ideas and stimulate discussion 2 Arthur Miller – his life and times within our classrooms while allowing a huge range of performance opportunities. The play moves at such a pace Timeline and we as an audience are never allowed to lose our focus as scene after scene unravels in front of our eyes. There 3 The Crucible in context is an inevitability in the outcome which fascinates and The Salem Witch Trials enthralls us all. McCarthyism & Cold War USA We know John Proctor is doomed from the minute we first meet him and can guess that things will not end well 4 Mass hysteria for most people in the play. The moments of great drama, both on and off the stage, are so brilliantly realised within 5 Exploring the story – Act by Act this extraordinary story, which we know actually took place over 300 years ago. Not only this, but it all took place in a 7 Characters in The Crucible new country on the edge of civilisation. There is something so otherworldly about the crazy 9 An exploration of themes collapse of civic and moral order in Salem that we Intolerance can stand back and look in wonder that anything so ridiculous could be allowed to happen, and with such Fear tragic consequences. -

TIMELINE from 1886, Joe Keller's Birth Year, to 1948, When the Film

TIMELINE from 1886, Joe Keller’s birth year, to 1948, when the film version of ALL MY SONS was released A selected chronology of the life and times of Arthur Miller, and the events of ALL MY SONS. Attention has been paid to historical events which would influence Miller’s politics and writing. Playwright/Events from ALL MY SONS US and World History 1886 The year Joe Keller, 61 in 1947, would have been born. 1895 The year Kate Keller, 52 in 1947, would have been born. 1915 Arthur Asher Miller is born October 17 in New York City 1914‐1918 Europe is engaged in World War I (NYC) to Isidore, owner of the Miltex Coat and Suit (WWI). Company, and Augusta Miller. He is the second of three children, joining older brother Kermit. His family is wealthy 1915 The US House of Representatives rejects a and lives on Central Park North. They have a chauffeur, and proposal to give women the right to vote maintain a summer bungalow for the extended family in D.W. Griffith’s controversial film The Birth Far Rockaway, New York (NY). of a Nation is produced in the US The first fighter plane is used by a French The year Chris Keller, 32 in 1947, would have been born. pilot to gun down a German observation plane George Deever is born the same year. Charlie Chaplin produces and performs in . the silent film The Tramp. His character, The Little Tramp, who would appear in several more of his films, embodied Chaplin's social commentary, while critical of the faults and excesses created by industrialization, also shows support and belief in the “American Dream”. -

Arthur Miller's the Crucible

Bloom’s GUIDES Arthur Miller’s The Crucible New Edition CURRENTLY AVAILABLE Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Joy Luck Club All the Pretty Horses The Kite Runner Animal Farm Lord of the Flies The Autobiography of Malcolm X Macbeth The Awakening Maggie: A Girl of the Streets The Bell Jar The Member of the Wedding Beloved The Metamorphosis Beowulf Native Son Black Boy Night The Bluest Eye 1984 Brave New World The Odyssey The Canterbury Tales Oedipus Rex Catch-22 Of Mice and Men The Catcher in the Rye One Hundred Years of Solitude The Chosen Pride and Prejudice The Crucible Ragtime Cry, the Beloved Country A Raisin in the Sun Death of a Salesman The Red Badge of Courage Fahrenheit 451 Romeo and Juliet A Farewell to Arms The Scarlet Letter Frankenstein A Separate Peace The Glass Menagerie Slaughterhouse-Five The Grapes of Wrath Snow Falling on Cedars Great Expectations The Stranger The Great Gatsby A Streetcar Named Desire Hamlet The Sun Also Rises The Handmaid’s Tale A Tale of Two Cities Heart of Darkness Their Eyes Were Watching God The House on Mango Street The Things They Carried I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings To Kill a Mockingbird The Iliad Uncle Tom’s Cabin Invisible Man The Waste Land Jane Eyre Wuthering Heights Bloom’s GUIDES Arthur Miller’s The Crucible New Edition Edited & with an Introduction by Harold Bloom Bloom’s Guides: The Crucible—New Edition Copyright © 2010 by Infobase Publishing Introduction © 2010 by Harold Bloom All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Arthur Miller

PUSHING THE LIMIT: AMERICAN INDUSTRY DURING WORLD WAR II The American home front during World War II is essen- men were perishing on the European and Pacific fronts. It conditioners, washing machines and dryers, etc.) to com- tially a lesson in basic economics: as demand for war was a dichotomy that was both unconscionable and un- plex tank and aircraft parts. materiel skyrocketed, supply congruously followed avoidable, given the desperate need for material and the The automobile industry, for example, produced z suit—fueled by a workforce that previously had seen inevitable profits earned from producing it. roughly three million cars in 1941. However, in the years unemployment figures of 24.9 percent just eight years As early as December 1941, spending on military pre- following Pearl Harbor, fewer than 400 new vehicles were earlier. In the words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt: paredness had reached a stunning $75 million a day. Over manufactured as the factories were retooled to produce “Dr. New Deal was replaced by Dr. Win the War.” the next four years war material production continued to tanks, aircraft and military trucks. The demand for planes The aircraft industry is prime example of this surge in skyrocket: By 1945, the United States had produced more was so high that pilots were known to sleep on cots out- national production: In May 1940, during the same than 88,000 tanks, 257,000 artillery weapons, 2,679,000 side the major plants, waiting to fly the planes away as week The Netherlands government surrendered to machine guns, 2,382,000 military trucks and 324,000 war- they came off the production lines. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521605539 - Arthur Miller: A Critical Study Christopher Bigsby Excerpt More information INTRODUCTION Henrik Ibsen’s writing career stretched over forty-seven years, Strindberg’s over thirty-seven. Chekhov’s lasted twenty years. In 2002, sixty-six years had passed between Arthur Miller’s No Villain, a university play which won two prizes, and Resurrection Blues, voted best new play first produced outside New York. Two years on, in 2004, came Finishing the Picture. Longevity, of course, is no virtue, unless you happen to be a Galapagos turtle. In Miller’s case, however, nearly seventy years as a writer had seen a succession of plays that served to define the moral, social and political realities of twentieth- and then twenty-first-century life. At the turn of the millennium, British playwrights, actors, directors, reviewers and critics voted him the most significant playwright of the twentieth century with two of his plays (Death of a Salesman and The Crucible)intheirtopten. Curiously, he had fallen out of favour in his native America for the previous thirty years. His new plays were not well received, even as his classic plays of the 1940s and 50s were taught in schools and universities and regularly revived. Elsewhere in the world, however, his plays of the 1970s, 80s and 90s found a ready audience. In 1994, Broken Glass, his play set at the time of Kristallnacht, was poorly received in New York while winning the Olivier Award, in Britain, as best play of the year. In part, this is a story of poor productions in America, in part of those drawn to what seemed to them more innovative theatrical figures: European absurdists, the American avant-garde. -

Religion Five Years After the Crucible Was First Produced, Historian Edmund S

Religion Five years after The Crucible was first produced, historian Edmund S. Morgan offered this trenchant summary of Puritanism’s inherent religious tensions: Puritanism required that a man devote his life to seeking salvation but told him he was helpless to do anything but evil. Puritanism required that he rest his whole hope in Christ but taught him that Christ would utterly reject him unless before he was born God had foreordained his salvation. Puritanism required that man refrain from sin but told him that he would sin anyhow. Puritanism required that he reform the world in the image of God’s holy kingdom but taught him that the evil of the world was incurable and inevitable. Puritanism required that he work to the best of his ability at whatever task was set before KLP DQG SDUWDNH RI WKH JRRG WKLQJV WKDW *RG KDG ¿OOHG WKH ZRUOG with but told him he must enjoy his work and his pleasures only, as it ZHUHDEVHQWPLQGHGO\ZLWKKLVDWWHQWLRQ¿[HGRQ*RG Miller’s play reflects this constellation of paradoxes in its characters’ earnest seeking after truth despite their blindness to their own ignorance, their determination to root out evil wherever they might find it except in their own assumptions and beliefs, and in their longing for a perfectly moral life that would dominate their irrepressible human passions. For them, the devil was a spiritual reality that encompassed these and other barriers to a pious and godly life. As Miller himself commented, religious faith is central to the play’s intent: The form, the shape, the meaning of The Crucible were all compounded out of the faith of those who were hanged.