The First Case of Application of the New Motor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MERCEDES-BENZ Prepared By

Bhartidasan University Tiruchirappalli Project Report On MERCEDES-BENZ Prepared By MAHESHKUMAR DEVARAJ MBA 2ND SEM Roll no. :-BM100728 Exam no:- 10295229 Guided By Professor:- Mr. Abhijit rane College:- Mumbai school of business Academic Year July 2010-july 2012 Submitted To Bhartidasan University Tiruchirappalli DECLARATION I Maheshkumar Devaraj, student of MBA of Mumbai school of Business hereby declare that the project work presented in this report is my own work. The aim of this study is to understand the general information of Mercedes-Benz. I guarantee that this project report has not been submitted for the awards to any other university for degree, diploma or any other such prizes. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the Project Report entitled “An Overview of Mercedes-Benz ” is a bonafied of project work done by MAHESHKUMAR DEVARAJ submitted to the Bharathidasan University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION and that the dissertation has not previously formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associate ship, Fellowship or other title and that the project report represents independent and original work on the part of the candidate under my guidance. Signature of the Guide Signature of the Supervisor Signature of the Coordinator Director Signature of the Internal Examiner Signature of the External AKNOWLEDGEMENT A successful project can never be prepared by the single effort of the person to whom project is assigned, but it also the hardwork and guardianship of some conversant person who helped the undersigned actively or passively in the completion of successful project. -

KSM PM Opening Muenchen EN 19-07

Munich, 28. June 2019: CITIC Dicastal & KSM Castings open Engineering Office in Munich Efficient development and project work on a global level with important OEMs. These are the expectations, which the new Engineering Office in Munich has to fulfill. Its inauguration took place on 28. June. „A fast and targeted communication between customer and supplier is of great importance, especially at international projects“, stressed Vicente Perez-Lucerga, CEO of the KSM Castings Group, as part of his welcome speech. “Our en- gineering office in Munich is a logical step for an efficient advanced development, development and project work with the main customers of KSM and Dicastal in the South of Ger- many”. “Our new site will also help us to efficiently manage the global challenges resulting from different languages, time zones and intercultural differences and guarantees a good and professional work flow”, added Markus Kleemann, Man- ager of the new office. Interesting specialized lectures about ambitious technical items by Markus Kleemann (KSM Castings Group), Rüdiger Heim (The Fraunhofer Institute for Structural Durability and System Reliability LBF) and Gerrit Gerland (Co-Improve GmbH & Co KG), to challenging topics and an intensive exchange of expertise completed the program. In addition to the approxi- mately 50 invited guests, Vincent Nie, member of the super- visory board, also participated at the opening ceremony. Meanwhile, CITIC Dicastal and the KSM Castings Group are fully developed as global partners for the car industry. The position to meet the challenges of the mobility change is ex- cellent, also with this new site in close proximity to many well-known OEMs in the Quartier City II, Bauhausplatz 6, in 80807 München. -

Transformation Jetzt! 53

SUPPLY NETWORKS BUSINESS ANALYTICS RISIKEN VERRINGERN STRATEGIE 2025 BOTS, KI & CO. TRANSFORMATION JETZT! 53. SYMPOSIUM EINKAUF LOGISTIK TRANSFORMATION JETZT! IHR KONGRESS • Für Ihr Tagesgeschäft: Jetzt richtig aufgestellt für die Zukunft! Wohin steuern die Märkte? Wie beherrsche ich die Risiken? Was sind die richtigen Strategien und Organisationsformen? Welche Unterstützung bieten die neuen Technologien? • Ihre individuelle Agenda: Parallele Fachkonferenzen, interaktive Sessions und Diskussionsrunden – gestalten Sie sich IHREN personalisierten Kongress nach Ihren Schwerpunktthemen! IHR MEHRWert • DIE Plattform der Experten: Mit rund 2.000 Teilnehmern, 100 Ausstellern und 100 Referenten – einer der größten Kongresse für Einkauf & Supply Management • Wissen aus erster Hand: Konzerne, KMUs, Politik und Wissen- schaft – Sie erhalten Einblick in erprobte Lösungen, Zukunftsszenarien und aktuelle Studien. IHR NETZWERK • Auf Augenhöhe: Fach- und Führungskräfte aus Einkauf, Supply Chain Management und Projektmanagement: Mehr als 70% der Teilnehmer gehören zur ersten und zweiten Führungsebene. • Branchenübergreifend: Über 50% der Teilnehmer kommen aus der verarbeitenden Industrie, weitere 25% aus dem Dienstleistungs- und Finanzsektor: Ihre Chance zum Benchmarking und zum Blick über den Tellerrand! Raumplan Schöneberg I – III FK MS Charlottenburg I – III FK MS KONFERENZBEREICH 2. ETAGE WS Köpenick I – III Check FK17 YP Foyer FK Tiergarten I – III MS Chess Rook FK17 FK17 i Potsdam III Potsdam I Gartenlounge II BME Lounge FK FK MS MS Bishop Knight -

October 2020

GazetteOctober 2020 MERCEDES-AMG S65 WALES IN TWO SLS 15 YEARS WITH A 250CE E36 AMG RESTORATION THE OFFICIAL MERCEDES-BENZ CLUB FOUNDED 1952 What’s inside... Regulars 4 CLUBINFORMATION 32 4 CLUBPUBMEETINGS 5 DIARYDATES 5 INVITATIONRECEIVED 7 NEWS&VIEWS 13 YOURLETTERS 26 CLUBSHOP FEATURES 49 Car of the month 27 Grand finale 50 15 years and counting 63 REGIONALREPORTS 32 BTCC TECHNICAL CORNER 79 SPECIALNOTICES 34 Rob writes... 54 E36 AMG 81 NEWMEMBERS 41 Land of my fathers 58 Spares register 45 F1 news 59 Detailing 81 SPECIALNOTICES 47 From deep in the Archive 85 CARSFORSALE 41 50 54 Gazette Membership benefits First ever Mercedes-Benz Club Members’ website forum Published by The Mercedes-Benz Club – founded 1952 Free subscription to Mercedes-Benz Gazette copy dates Only UK club recognised by Classic magazine December October 16 January November 13 Mercedes-Benz Discounts from parts suppliers Monthly Gazette Discounts from hotels Editorial Office: Chris Bass, Tel: 01483 481836. Technical support 30 Scotgate, Stamford PE9 2YQ Unique archive of photos, brochures E-mail: [email protected] Discounted insurance and technical literature Advertising, Design and Production: Hine Marketing, Club shop Tel: 01452 730770 MercedesBenzClubUK Hill Farm Studios, Wainlodes Lane, Bishops Norton Local, national and international events Gloucestershire GL2 9LN Discounts from many MB dealers themercedesbenzclub/ E-mail: [email protected] Gazette distribution queries: Catherine Barlow, For membership and general enquiries Tel: 01780 482111 (9.00am to 5.00pm Monday to Friday) telephone 01780 482111, 0345 6032660 (9.00am to 5.00pm Monday to Friday) 30 Scotgate, Stamford PE9 2YQ E-mail: [email protected] or see www.mercedes-benz-club.co.uk NEWS&VIEWS ALL GAZETTES NOW ON THE WEBSITE Club Director John Wallis has now completed the extraordinary task of getting scans of Why do so many all the Club Gazettes, from issue one in 1952 to the latest, onto the Club website. -

Wie Sind Sie Eigentlich? 5

audibkk.de /gesundheit Das Magazin der Audi BKK 01.2017 5 trend Buddhismus Wie to go. GEWINN- 14 SPIEL! Jetzt mitmachen & gewinnen! gesund & vital 2 x Wellness-Wochenende cook&fit: 15 x Fitness-Minis: 90 Workouts für jeden Tag und überall Fitness im Wohnzimmer. 30 sind Sie eigentlich? Digital Detox. Ab Seite 6 – Anzeige – Audi BKK Magazin /inhalt /intro Jetzt. Oder nie. Ihr Feedback ist uns wichtig! Wir freuen uns 1 auf Ihre Ab 1,39% p. a. in Ihr Traumhaus. Anregungen, Wünsche und 6 Vorschläge. /spezial lobundkritik@ audibkk.de Ihr Service für Baufinanzierungen der Audi Bank. Digital Detox Liebe Leserin, lieber Leser, Weniger Stress durch Digital Detox? Über 400 Banken und Sparkassen im Vergleich! Besuchen Sie uns in einer unserer Filialen. Die neue Life-Media-Balance funktioniert falls Sie dieser Tage über das Arzneimittelversorgungsstärkungs- Machen Sie gleich Ihren persönlichen Zins-Check unter: www.audibank.de/baufinanzierung Unsere Filialen finden Sie unter in drei Schritten: ausschalten, gesetz stolpern sollten, dann sind Sie vielleicht schon dem www.audibank.de/baufi-filialen abschalten, ankommen. „Unwort des Jahres 2017“ begegnet. Das Gesetz, das jetzt vom Ab 5,19 Euro pro Monat: Mit einer Risiko-Lebensversicherung erhalten Sie den perfekten Terminvereinbarung: Bundestag verabschiedet wurde, sollte – wie der Name schon Schutz für Ihr Baudarlehen. 0531 212-859659 14 sagt – der Verbesserung der Arzneimittelversorgung dienen. Vor Jetzt neu: Live-Beratung bequem von allem stehen die Interessen der Pharmaindustrie im Vorder- Der Service für Baufinanzierungen1 ist ein Angebot der Audi Bank, Zweig niederlassung der zu Hause aus. Rufen Sie uns an und Volkswagen Bank GmbH. /gesund & vital grund, wie auch der Spitzenverband der Gesetzlichen Kranken- erleben Sie die Online Live-Beratung – Draußen ist besser als versicherung kritisiert. -

Good Design 2014 Awarded Product Designs and Graphics and Packaging

GOOD DESIGN 2014 AWARDED PRODUCT DESIGNS AND GRAPHICS AND PACKAGING THE CHICAGO ATHENAEUM: MUSEUM OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN THE EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURE ART DESIGN AND URBAN STUDIES ELECTRONICS 2014 BeoLab 18, 2013 Designers: Torsten Valeur, David Lewis Designers, Copenhagen, Denmark Manufacturer: Bang & Olufsen A/S, Struer, Denmark Carbide Series® SPEC Range PC Gaming Case, 2014 Designers: BMW Group DesignworksUSA, Newbury Park, CA, USA Manufacturer: Corsair, Fremont, CA, USA Simple Audio Listen Speakers, 2013 Designers: BMW Group DesignworksUSA, Newbury Park, CA, USA Manufacturer: Corsair, Fremont, CA, USA Bretford, Inc. PowerRack® for iPad 2, 2012 Designers: Cesaroni Design Associates, Inc., Glenview, IL, USA Manufacturer: Bretford, Inc., Franklin Park, IL, USA JBL GX, 2014 Designers: Kasin Chan, LDA, Irvine, CA, USA Manufacturer: Harman International, Northridge, USA Moto X, 2013 Designers: Consumer Experience Design Team, Motorola Mobility LLC, Chicago, IL, USA Manufacturer: Motorola Mobility LLC, Chicago, IL, USA Big Turtle Shell, 2013 Designers: Caro Krissman, Outdoor Tech, Los Angeles, CA, USA Manufacturer: Outdoor Tech, Los Angeles, CA, USA Motorola Solutions TC55 Touch Computer, 2013 Designers: Innovation & Design, Motorola Solutions, Inc., Holtsville, NY, USA Manufacturer: Motorola Solutions, Inc., Holtsville, NY, USA Logitech Broadcaster, 2012 Designers: Chris Loew, Brett Newman, Leo Kopelow, Sven Newman, Chris Loew, Brett Newman, Leo Kopelow, Sven Newman, Daylight, San Francisco, CA, USA Manufacturer: Logitech, Newark, CA, USA Dropcam Pro, 2013 Designers: Dan Harden, Rob Strickler, Whipsaw Inc, San Jose, CA, USA Manufacturer: Dropcam, San Francisco, CA, USA Good Design Awards 2014 Page 1 of 50 October 31, 2014 © 1992-2015 The Chicago Athenaeum - Use of this website as stated in our legal statement. -

From Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Audi Type Private Company

Audi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Audi Private company Type (FWB Xetra: NSU) Industry Automotive industry Zwickau, Germany (16 July Founded 1909)[1] Founder(s) August Horch Headquarters Ingolstadt, Germany Production locations: Germany: Ingolstadt & Neckarsulm Number of Hungary: Győr locations Belgium: Brussels China: Changchun India: Aurangabad Brazil: Curitiba Area served Worldwide Rupert Stadler Key people Chairman of the Board of Management, Wolfgang Egger Head of Design Products Automobiles, Engines Production 1,143,902 units (2010) output (only Audi brand) €35.441 billion (2010) Revenue (US$52.57 billion USD) (including subsidiaries) €1.850 billion (2009) Profit (US$2.74 billion USD) €16.832 billion (2009) Total assets (US$25 billion USD) €3.451 billion (2009) Total equity (US$5.12 billion USD) Employees 46,372 (2009)[2] Parent Volkswagen Group Audi do Brasil e Cia (Curitiba, Brazil) Audi Hungaria Motor Kft. (Györ, Hungary) Audi Senna Ltda. (Brazil) Automobili Lamborghini Subsidiaries Holding S.p.A (Sant'Agata Bolognese, Italy) Autogerma S.p.A. (Verona, Italy) quattro GmbH (Neckarsulm, Germany) Website audi.com Audi AG (Xetra: NSU) is a German automobile manufacturer, from supermini to crossover SUVs in various body styles and price ranges that are marketed under the Audi brand (German pronunciation: [ˈaʊdi]), positioned as the premium brand within the Volkswagen Group.[3] The company is headquartered in Ingolstadt, Germany, and has been a wholly owned (99.55%)[4] subsidiary of Volkswagen AG since 1966, following a phased purchase of its predecessor, Auto Union, from its former owner, Daimler-Benz. Volkswagen relaunched the Audi brand with the 1965 introduction of the Audi F103 series. -

Lic No. DBA Indicator Business Name Business Address License

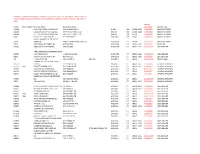

Connecticut Dealer and Repairer License List as of 09/27/2021 - PLEASE NOTE THAT LICENSEES HAVE 45 DAYS FROM EXPIRATION DATE TO RENEW LICENSE BEFORE LICENSE IS CANCELED BY DMV License Lic No. DBA Indicator Business Name Business Address Expiration License Type M1026 SPARTAN CARGO TRAILERS LLC 140 BUSINESS BLVD ALMA GA 31510-7667 6/30/2023 MANUFACTURER M1013 EAGLE SPECIALTY VEHICLES LLC 3344 STATE ROUTE 132 AMELIA OH 45102-2249 6/30/2022 MANUFACTURER M1014 KELLERMAN COACHWORKS INC 3344 STATE ROUTE 134 AMELIA OH 45102 6/30/2022 MANUFACTURER M942 KTM NORTH AMERICA INC 1119 MILAN AVE AMHERST OH 44001 6/30/2023 MANUFACTURER ISUZU COMMERCIAL TRUCK OF M801 AMERICA 1400 S DOUGLASS RD STE 100 ANAHEIM CA 92806 6/30/2023 MANUFACTURER J2629 ANDOVER AUTO PARTS INC 497 ROUTE 6 ANDOVER CT 06232-1320 4/30/2022 RECYCLER U5236 DUBOIS AUTOMOTIVE INC 343 ROUTE 6 ANDOVER CT 06232-1319 12/31/2022 USED DEALER X PRO MOTORCYCLE PERFORMANCE U8237 TECHNOLOGY INC 5 BUNKER HILL RD ANDOVER CT 06232-1334 11/30/2022 USED DEALER U960 ANDOVER AUTO PARTS INC 497 ROUTE 6 ANDOVER CT 06232-1320 8/31/2023 USED DEALER N2 FITZPATRICKS INC 430 E MAIN ST BOX 206 ANSONIA CT 06401 11/30/2021 NEW DEALER CONN DEPT EDUCATION EMMETT R1371 OBRIEN 141 PRINDLE AVE ANSONIA CT 06401-2561 2/28/2023 GENERAL REPAIRER R1371 DBA EMMETT OBRIEN RVTS 141 PRINDLE AVE ANSONIA CT 06401-2561 2/28/2023 GENERAL REPAIRER R4508 V AND M INC OF ANSONIA 472 MAIN ST ANSONIA CT 06401 8/31/2022 GENERAL REPAIRER R6524 CHIPPYS SERVICE STATION LLC 136 WAKELEE AVE ANSONIA CT 06401 6/30/2022 GENERAL REPAIRER R6826 -

Mercedes-Benz Daripada Wikipedia, Ensiklopedia Bebas

Mercedes-Benz Daripada Wikipedia, ensiklopedia bebas. (Dilencongkan dari Mercedes Benz) Mercedes-Benz Jenis Anak syarikat Pendahulu Benz & Cie. Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft Ditubuhkan 1886 Pengasas Karl Benz Ibu pejabat Stuttgart, Jerman Tempat dibekalkan Antarabangsa Perancang utama Dieter Zetsche, Pengerusi Produk Kereta Lori Bus Enjin Servis Perkhidmatan kewangan Induk Daimler AG Pembahagian Mercedes-Benz AMG Laman web mercedes-benz.com Mercedes-Benz ialah sebuah syarikat pengeluar kereta multinasional dari Jerman milikan Daimler AG, dan merupakan jenama yang digunakan untuk kereta mewah, bas, dan lori. Ibu pejabat Mercedes-Benz teletak di Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg, Jerman. Isi kandungan [sorokkan] 1 Sejarah 2 Sukan bermotor 3 Pengilangan 4 Model o 4.1 Penamaan model o 4.2 Kenderaan komersial 5 Penala o 5.1 Penala lain 6 Inovasi 7 Lihat juga 8 Pautan luar Sejarah[sunting | sunting sumber] Benz Patent Motorwagen 1886 (Replika). Kereta sebenar pertama di dunia. Benz Velo 1894. Sejarah Daimler-Benz bermula seawal 1880-an apabila Karl Benz (1844–1929) dan Gottlieb Daimler (1834–1900), bekerja denganWilhelm Maybach (1846–1929), masing-masing mencipta kereta yang digerakkan enjin pembakaran dalaman di selatan Jerman. Walaupun mereka hanya dipisahkan jarak sejauh 60 batu, masing-masing tidak menyedari hasil kerja satu sama lain. Karl Benz mempunyai sebuah kedai di Mannheim dan mencipta kereta sebenar pertama yang digerakkan oleh enjin pembakaran dalaman pada 1885. Kereta beroda tiga tersebut dinamakan sebagai Benz Patent Motorwagen. Sementara itu pula, Gottlieb Daimler dan rakan rekabentuknya Maybach, mencipta prototaip bagi rekaan enjin petrol model, dikenali sebagai "enjin jam besar"(grandfather clock engine). Kedua-dua Benz dan Daimler membuka syarikat kereta masing- masing iaitu Benz & Cie. -

Liebe Leserinnen Und Leser, Ausgabe 06/08 Neues Logistikcenter Bei FK

Ausgabe 06/08 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, das letzte Highlight des Jahres, die Essen Motor Show, steht in den Startblöcken. Vom 28. November bis zum 07. Dezember können wieder nette Partys gefeiert, Kontakte geknüpft, Freundschaften gepflegt und Geschäftsverbindungen geschlossen werden. Dass dies alles auch über die Internetplattform XING geht, habe ich gerade gelernt. Das professionelle, globale Netzwerk verspricht mehr als 6 Millionen Mitglieder weltweit und jede Menge Geschäftsverbindungen in alle Branchen. Als Redakteur von TUNING-INSIDE sollte man(n) selbstverständlich up to date sein, was die modernen Kommunikationsmittel im Businessbereich anbelangt. Glücklicherweise gibt es nette Mitmenschen, welche bei Bedarf diesem Missstand mit einem einfachen Mausklick ein Ende bereiten. Als mich Sigrid Pinke vom Delius-Klasing-Verlag auf XING ansprach, fühlte sie wohl schon bei der Fragestellung, dass ich kein XINGianer bin. Im Handumdrehen wurde ich per E-Mail eingeladen und kann mich nun im weltweiten Netzwerk austoben. Doch zuerst werde ich einige Partys besuchen und meine persönlichen Kontakte auf der Show in Essen pflegen. So, nun viel Spaß beim Lesen. Ihr Andreas K. Bauer Borbet wählt Werbestar Seit Anfang Oktober steht der Gewinner der neuen Borbetaktion „Dein Auto als Borbet-Wer- bestar“ fest. Zehn Finalisten wählte eine Jury aus einer Vielzahl von Bewerbern aus, unter de- nen Robin Hanke aus Greußen mit seinem Opel Vectra B Sport am Ende als Sieger hervorging. Auf dem zweiten Rang platzierte sich Olaf El- v.l.n.r Robin Hanke, Dirk Borbet, Ebru Dayi, Robin Hanke mit seinem Opel Vectra B lerhausen gefolgt von Ebru Dayi. Neben einem Olaf Ellerhausen Satz Borbet Aluräder konnten die Erstplatzier- ten auch eine Scheck mit nach Hause nehmen. -

Scientific Overview 50829 Köln Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research

Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research Plant Breeding Max Planck Institute for Max Planck Institute Tel: +49 (221) 5062-0 for Plant Breeding Research Fax: +49 (221) 5062-674 Carl-von-Linné-Weg 10 E-Mail: [email protected] Scientific Overview 50829 Köln www.mpipz.mpg.de Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research Max-Planck-Institut für Max-Planck-Institut für Pflanzenzüchtungsforschung Pflanzenzüchtungsforschung Scientifi c 2014 Overview Scientifi Cover picture (Peter Huijser): False-colour fl uorescence microscopy image of young compound leaves developing at the shoot apex of hairy bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta). The nuclei of all epidermal cells light up as tiny dots due to the accumulation of an expressed transgenic fl uorescent protein. This image illustrates the re- search in the new Department of Comparative Development and Genetics aimed at under- standing how biological forms develop and diversify. Max-Planck-Institut für Pflanzenzüchtungsforschung Scientific Overview 2014 Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research 2 Table of Contents The entire world we apprehend through our senses is no more than a tiny fragment in the vastness of Nature. Max Planck (1858 - 1947) from his book “The Universe in the Light of Modern Physics” (1931) Page 8 (Translated by W.H. Johnston) 3 Table of Contents Welcome to our Institute 5 Independent Research Groups Historical background to the Institute 6 and Research of Service Groups 61 Organization and governance of the Institute 8 Evolution of obligate parasitism and biodiversity -

Der Erfolg Des Automobils Und Das Zauberlehrlings-Syndrom

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Canzler, Weert Book Part Der Erfolg des Automobils und das Zauberlehrlings- Syndrom Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Canzler, Weert (1997) : Der Erfolg des Automobils und das Zauberlehrlings-Syndrom, In: Meinolf Dierkes (Ed.): Technikgenese: Befunde aus einem Forschungsprogramm, ISBN 3-89404-169-2, Edition Sigma, Berlin, pp. 99-129 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/122449 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu WZB-Open Access Digitalisate WZB-Open Access digital copies Das nachfolgende Dokument wurde zum Zweck der kostenfreien Onlinebereitstellung digitalisiert am Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung gGmbH (WZB). Das WZB verfügt über die entsprechenden Nutzungsrechte.