The Weight of Silk: an Exploratory Account Into the Developing Relations Between Byzantium and China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Review of the Silk Road

International Journal of New Developments in Engineering and Society ISSN 2522-3488 Vol. 5, Issue 1: 47-49, DOI: 10.25236/IJNDES.2021.050110 A historical review of the Silk Road Yurui Xu Nanjing Foreign Language School, Nanjing, Jiangsu, 210009, China Abstract: During the process of trade, some factors can decide whether the trade can continue fluently and which side has more dominance. This essay will focus on the trade of ancient China and the Silk road to discuss which factor has an important influence on the trade and explain the background and reasons. When ancient China was in strong period, like the early period of Tang dynasty (China at that time was one of the most powerful countries among the world), Chinese government had more trade dominance as they didn’t necessarily rely on the goods of foreign merchants. However, with the decline of Chinese power, its trade dominance decrease at the same time and the government gradually lost its control of the Silk Road. Consequently, Chinese government began to develop other trade routes-- the Maritime Silk Road. Keywords: Trade dominance; Control of The Silk Road; Changes of power of Ancient China; Maritime Silk Road 1. Introduction In this ever-changing world, China continues to embrace the world with its opening up policy and defend globalization. Since 2013 the Belt and Road Initiative has attracted a lot of investors outside of China. From South Asia to Western Europe, 65 countries have signed for the project, which connects China with partners all the way to Europe. The idea of BRI originates from the ancient Silk Road where merchants from the Han Dynasty traded with partners mainly from Central Asia. -

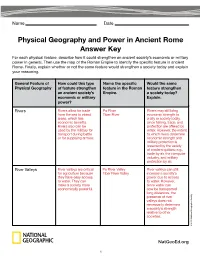

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

Introduction: Missing Years

Cambridge University Press 0521855829 - Caesar’s Legacy: Civil War and the Emergence of the Roman Empire Josiah Osgood Excerpt More information Introduction: missing years As a youth, the future emperor Claudius set out to write the recent history of Rome and, with initial encouragement from Livy, then the greatest living historian, produced an account that began with the assassination of Julius Caesar. Some were less supportive. Claudius’ mother, Antonia, and grandmother, Livia, repeatedly criticized his efforts; he could not write as frankly as he wished. Thus warned, Claudius left in his final version the assassination and its immediate aftermath, but omitted everything that 1 happened in the civil wars that followed: an eloquent silence. This book is in one sense an effort to recover what Claudius left out and why. Its reader will have to face up to the killing squads, the land confiscations, the famine, the propaganda, the agonizing dilemmas of these years. But I have not set out to write the kind of political narrative Claudius would have produced. For if the emperor has been one inspiration, another has been Vergil, whose first and ninth Eclogues exemplify how civil war swept through the lives of ordinary Italians during Claudius’ missing years. My work too aims to retrieve the men and women who fought and endured the bloody struggles that beset the Roman world under the triumvirate of Mark Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus. It is all too easy in writing about these years to focus only on high politics and constitutional questions, and the results become depressingly top-heavy. -

Supplied Through the Parthians) from the 1St Century BC, Even Though the Romans Thought Silk Was Obtained from Trees

Chinese Silk in the Roman Empire Trade with the Roman Empire followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians) from the 1st century BC, even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees: The Seres (Chinese), are famous for the woolen substance obtained from their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves... So manifold is the labor employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman maiden to flaunt transparent clothing in public. -(Pliny the Elder (23- 79, The Natural History) The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral: I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body. -(Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE- 65 CE, Declamations Vol. I) The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (perhaps the Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE: Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. -

11Ffi ELOGIA of the AUGUSTAN FORUM

THEELOGIA OF THE AUGUSTAN FORUM 11ffi ELOGIA OF THE AUGUSTAN FORUM By BRAD JOHNSON, BA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Brad Johnson, August 2001 MASTER OF ARTS (2001) McMaster University (Classics) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Elogia of the Augustan Forum AUTHOR: Brad Johnson, B.A. (McMaster University), B.A. Honours (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Claude Eilers NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 122 II ABSTRACT The Augustan Forum contained the statues offamous leaders from Rome's past. Beneath each statue an inscription was appended. Many of these inscriptions, known also as elogia, have survived. They record the name, magistracies held, and a brief account of the achievements of the individual. The reasons why these inscriptions were included in the Forum is the focus of this thesis. This thesis argues, through a detailed analysis of the elogia, that Augustus employed the inscriptions to propagate an image of himself as the most distinguished, and successful, leader in the history of Rome. III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Claude Eilers, for not only suggesting this topic, but also for his patience, constructive criticism, sense of humour, and infinite knowledge of all things Roman. Many thanks to the members of my committee, Dr. Evan Haley and Dr. Peter Kingston, who made time in their busy schedules to be part of this process. To my parents, lowe a debt that is beyond payment. Their support, love, and encouragement throughout the years is beyond description. -

Trade and Political Fragmentation on the Silk Roads: the Economic and Cultural Effects of Historical Exchange Between China and the Muslim East

Trade and Political Fragmentation on the Silk Roads: The Economic and Cultural Effects of Historical Exchange between China and the Muslim East Lisa Blaydes∗ Christopher Paiky February 2019 Abstract The Silk Roads stretched across Eurasia to connect East and West for centuries. At its height, the network of trade routes enabled merchants to travel from China to the Mediterranean Sea, carrying with them high-value commercial goods. Alongside inter- regional trade came political, economic and cultural exchange that were crucial for urban growth and prosperity. In this paper, we examine the extent to which urban centers thrived or withered as a function of political shocks to trade routes, particularly the fragmentation of state and imperial control along natural travel paths across Eurasia. In doing so, we challenge a Eurocentric approach to world history through an examination of exchange between the two most developed regions during the medieval and early modern periods, China and the Muslim East. We also trace one effect of historical trade on the contemporary period | forms of cultural diffusion that may persist into the contemporary period. ∗Department of Political Science, Stanford University yDivision of Social Science, New York University Abu Dhabi 1 In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping officially launched the \One Belt, One Road" Initiative later re-branded as the \Belt and Road" Initiative. Hailed as a new Silk Road, the project invests billions of dollars in infrastructure development to promote economic integration of China with -

The Edictum Theoderici: a Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy

The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy By Sean D.W. Lafferty A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Sean D.W. Lafferty 2010 The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy Sean D.W. Lafferty Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This is a study of a Roman legal document of unknown date and debated origin conventionally known as the Edictum Theoderici (ET). Comprised of 154 edicta, or provisions, in addition to a prologue and epilogue, the ET is a significant but largely overlooked document for understanding the institutions of Roman law, legal administration and society in the West from the fourth to early sixth century. The purpose is to situate the text within its proper historical and legal context, to understand better the processes involved in the creation of new law in the post-Roman world, as well as to appreciate how the various social, political and cultural changes associated with the end of the classical world and the beginning of the Middle Ages manifested themselves in the domain of Roman law. It is argued here that the ET was produced by a group of unknown Roman jurisprudents working under the instructions of the Ostrogothic king Theoderic the Great (493-526), and was intended as a guide for settling disputes between the Roman and Ostrogothic inhabitants of Italy. A study of its contents in relation to earlier Roman law and legal custom preserved in imperial decrees and juristic commentaries offers a revealing glimpse into how, and to what extent, Roman law survived and evolved in Italy following the decline and eventual collapse of imperial authority in the region. -

The Silk Road in World History

The Silk Road in World History The New Oxford World History The Silk Road in World History Xinru Liu 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Liu, Xinru. The Silk Road in world history / Xinru Liu. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-19-516174-8; ISBN 978-0-19-533810-2 (pbk.) 1. Silk Road—History. 2. Silk Road—Civilization. 3. Eurasia—Commerce—History. 4. Trade routes—Eurasia—History. 5. Cultural relations. I. Title. DS33.1.L58 2010 950.1—dc22 2009051139 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Frontispiece: In the golden days of the Silk Road, members of the elite in China were buried with ceramic camels for carrying goods across the desert, hoping to enjoy luxuries from afar even in the other world. -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S.