Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment Lango Sub-Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment Lango Sub-Region

April 2011 Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment Lango Sub-region Uganda ACF USA, Food Security and Livelihoods Assessment, April 2011 Uganda TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1. Purpose of the survey ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.2. Methods of the survey ............................................................................................................................... 12 2. Findings of the survey ......................................................................................................................................... 13 2.1. Demographic information .......................................................................................................................... 13 2.2. Household Dietary diversity and food sources .......................................................................................... 19 2.3. Household expenditures ............................................................................................................................ 25 2.4. Income sources and household assets ...................................................................................................... -

Otuke District Local Government

CALL TO ACTION THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA NUTRITION CHALLENGES/ GAPS CALL FOR ACTION RESPONSIBLE Otuke District Nutrition coordination committee Otuke was also supported to conduct a Food GOVERNANCE AREA OFFICE (DNCC), seven (7) Sub counties and One Security and Nutrition Assessments (FSNA). OTUKE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT Coordination and Weak coordination mechanisms of Partner mapping required to know who DNFP, CAO Town council trained on multi sectoral nutrition FSNA data was not available previously partnerships: nutrition actions at all levels. is where and doing what. DNCC/SNCC ADVOCACY BRIEF ON STRENGTHENING NUTRITION GOVERNANCE FOR MULTI-SECTORAL RESPONSE implementation for improved nutrition unavailable therefore this first FSNA data will members need to be oriented on their outcomes. be used as a baseline to compare progress roles and responsibilities in achievement of health, nutrition and WASH The district conducted quarterly DNCC meetings Establish joint planning and strategic indicators in subsequent FSNAs. Annual FSNAs and support supervision activities aimed at coordination mechanisms amongst will be conducted to assess annual progress. strengthening the accountability framework for partners in the district to reduce on Multisectoral nutrition actions implemented in The Otuke DNCC has been trained on nutrition duplication of resources and achieve sustainable results Otuke district. governance and supported to use reporting templates and monitoring tools previously Systems capacity Lack of clarity on nutrition sensitive Orientation -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

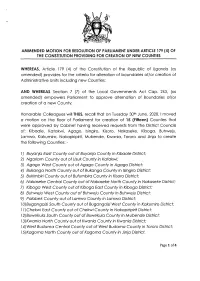

(4) of the Constitution Providing for Creation of New Counties

AMMENDED MOTTON FOR RESOLUTTON OF PARLTAMENT UNDER ARTTCLE 179 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION PROVIDING FOR CREATION OF NEW COUNTIES WHEREAS, Ariicle 179 (a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Ugondo (os omended) provides for the criterio for olterotion of boundories oflor creotion of Administrotive Units including new Counties; AND WHEREAS Section 7 (7) of the Locql Governments Act Cop. 243, (os omended) empowers Porlioment to opprove olternotion of Boundories of/or creotion of o new County; Honoroble Colleogues willTHUS, recoll thot on Tuesdoy 30rn June, 2020,1 moved o motion on the floor of Porlioment for creotion of I5 (Fitteen) Counties thot were opproved by Cobinet hoving received requests from the District Councils of; Kiboole, Kotokwi, Agogo, lsingiro, Kisoro, Nokoseke, Kibogo, Buhweju, Lomwo, Kokumiro, Nokopiripirit, Mubende, Kwonio, Tororo ond Jinjo to creote the following Counties: - l) Buyanja Eost County out of Buyanjo County in Kibaale Distric[ 2) Ngoriom Covnty out of Usuk County in Kotakwi; 3) Agago Wesf County out of Agogo County in Agogo District; 4) Bukonga Norfh County out of Bukongo County in lsingiro District; 5) Bukimbiri County out of Bufumbira County in Kisoro District; 6) Nokoseke Centrol County out of Nokoseke Norfh County in Nokoseke Disfricf 7) Kibogo Wesf County out of Kibogo Eost County in Kbogo District; B) Buhweju West County aut of Buhweju County in Buhweju District; 9) Palobek County out of Lamwo County in Lamwo District; lA)BugongoiziSouth County out of BugongoiziWest County in Kokumiro Districf; I l)Chekwi Eosf County out of Chekwi County in Nokopiripirit District; l2)Buweku/o Soufh County out of Buweku/o County in Mubende Disfricf, l3)Kwanio Norfh County out of Kwonio Counfy in Kwonio Dislricf l )West Budomo Central County out of Wesf Budomo County inTororo Districf; l5)Kogomo Norfh County out of Kogomo County in Jinjo Districf. -

Lira District Local Government Councils' Scorecard FY 2018/19

lirA DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 lira DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 L-R: Ms. Rose Gamwera, Secretary General ULGA; Mr. Ben Kumumanya, PS. MoLG and Dr. Arthur Bainomugisha, Executive Director ACODE in a group photo with award winners at the launch of the 8th Local Government Councils Scorecard Report FY 2018/19 at Hotel Africana in Kampala on 10th March 2020 with 89 parishes and 751 villages. By 1.0 Introduction 2020, Lira’s population is projected to be This brief was developed from the scorecard at 465,900; 230,400 male and 248,100 report titled, “The Local Government female (UBOS, 2018). Councils Scorecard FY 2018/19. The Next Big Steps: Consolidating Gains of Decentralisation and Repositioning the 1.2 The Local Government Councils Local Government Sector in Uganda”. Scorecard Initiative (LGCSCI) The brief provides key highlights of the The main building blocks in LGCSCI are performance of elected leaders and the principles and core responsibilities of Council of Lira District Local Government Local Governments as set out in Chapter during the FY2018/19. 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, the Local Governments Act (CAP 1.1 Brief about the district 243) under Section 10 (c), (d) and (e). The scorecard comprises of five parameters Lira district is located in the northern part based on the core responsibilities of of Uganda; bordered by Dokolo district in the local government Councils, District the south, Apac district and Kole district in Chairpersons, Speakers and Individual the west, Pader district and Otuke district Councillors. -

Request for Proposal

EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) EOI NO: 20-001 PART A: COVER PAGE EOI: 20-001 Issuance Date: May 21, 2020 Submission of EOI: Deadline for Receipt of EOI Applications: June 19, 2020 [5 pm, East Africa Time (EAT)] Submission to: [email protected] Request for Expression of Interest for Contractor Prequalification for the procurement of civil works – Rehabilitation of Selected Health Facilities in Uganda John Snow, Inc. (herein referred to as “JSI”), is an international public health firm and is currently implementing the Regional Health Integration to Enhance Services-North, Lango (RHITES-N, Lango) Project, funded by the USAID. The project will improve the use of integrated health services in Northern Uganda’s Lango sub region and strengthen the health system to sustain gains made by earlier projects. JSI is soliciting EOI from potential firms/companies for undertaking rehabilitation of selected health facilities at Dokolo HCIV in Dokolo District, Orum HCIV in Otuke District, and Ogur HCIV in Lira District. The procurement as a result of this solicitation and subsequent RFQ is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and is subject to all applicable Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and AID Acquisition Regulations (AIDAR). JSI will issue the Standard Bidding Document for the procurement of works along with detailed Bills of Quantities (BOQs), technical specifications and drawings to only approved prequalified contractors who will be selected in response to this solicitation and those meeting the eligibly criteria as prequalified contractor stated in this EOI. Please submit your expression of interest applications (EOI) in accordance with the instructions mentioned in this document. -

Otuke District HRV Profile.Pdf

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Otuke District Hazard, Risk, and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................i List of Figures .............................................................................................................. ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................ ii Acronyms.................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................v Executive Summary.................................................................................................... vi Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Objectives ....................................................................................................................1 Methodology ................................................................................................................1 Overview of the District................................................................................................4 Historical Background..................................................................................................4 Location .......................................................................................................................4 -

JLOS Construction Projects Update

CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS UPDATE December 2012 Edition Prepared by the JLOS Secretariat | Email: [email protected] www.jlos.go.ug | 1 NOTE: This is the December 2012 edition of the JLOS Construction Projects update. The content in this document will be updated in subsequent editions to reflect up-to-date status of various construction projects especially those that are ongoing. Watch out for the January 2012 Edition of the Construction Projects Update to be exclusively published on the JLOS Website: www.jlos.go.ug www.jlos.go.ug | 2 1. ADJUMANI DIRECTORATE OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS OFFICES DPP Offices- Front view DPP Offices- Side view DPP Offices- Rear view Name of Facility Newly constructed Adjumani DPP offices. Description of the 1 Office block and a gate house facilities Location Adjumani District Contractor Ishaka Muhereza building and Civil Engineering Contractors Financier Justice, Law and Order Sector Completion date Newly constructed www.jlos.go.ug | 3 Remarks The DPP staff have moved into their new offices 2. ADJUMANI POLICE HOUSING ADJUMANI- Police barracks Name of Facility Construction of Adjumani Police barracks Description of the 1 block of 10 housing units, 5 stances of latrines and bath shelters facilities Location Adjumani District Contractor Hotel Zawadi Ltd Cost of Construction (Excluding Vat) UGX: 150,000,000 Financier NETHERLANDS Completion date December 2010 Remarks The Police Officers have moved into their houses www.jlos.go.ug | 4 3. ADUKU COURT BUILDING ADUKU COURT BUILDING- Front view ADUKU COURT BUILDING- Side view ADUKU COURT BUILDING- Rear view ADUKU- Court room Name of Facility Newly constructed Aduku Court building- Aduku Description of Court building, Residential house for Judicial staff facilities Location Aduku District Contractor Dynamic Engineering Services Limited Financier DANIDA Date completed May 2012 Status Completed and in use www.jlos.go.ug | 5 4. -

Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) the REPUBLIC of UGANDA OFFICE of the PRIME MINISTER EUROPEAN UNION

Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU) THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER EUROPEAN UNION Building resilience to enhance food and nutrition security, income and health in Northern Uganda (BRENU) By Moureen Awori – IITA-Uganda Overall Goal To consolidate stability in Northern Uganda, eradicate poverty and under-nutrition and strengthen the foundations for sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development Project duration and funding Introduction Under the Development Initiative for Northern Uganda Total duration: 36 months (2020 - 2022) (DINU), a Government of Uganda programme supported Total budget: Euros 5,578,949 by the European Union and supervised by Office of the European Union (90%): Euros 5,021,054 Prime Minister, International Institute of Tropical Consortium (10%): Euros 557,895 Agriculture (IITA) has received a grant to implement the action, “Building resilience to enhance food and nutrition Target group security, incomes and health in Northern Uganda”. The project to be implemented by a consortium of partners, Smallholder farmer households with access to land seeks to enhance food and nutrition security, increase ≥1.5 acres, households that produce at least one household incomes and improve maternal and child target commercial commodities, farmer groups nutrition and health in Northern Uganda (NU) by and cooperatives, women of reproductive age (15- promoting diversified food production of resilient 49 years), children (6-24 months), adolescents (10 varieties, commercializing agriculture, encouraging -

TITLE of the MICRO-PROGRAMME: GS1247 – Improved Kitchen Regimes Multi Country Poa 1

TITLE OF THE MICRO-PROGRAMME:_GS1247 – Improved Kitchen Regimes Multi Country PoA ANNEX AO – THE GOLD STANDARD MICRO-PROGRAMME ACTIVITY DESIGN DOCUMENT TEMPLATE (VPA-DD) CONTENTS A. General description of micro-programme activity (VPA) B. Eligibility of VPA and Estimation of Emission Reductions C. Stakeholder comments Annexes Annex 1: Contact information on entity/individual responsible for the VPA Annex 2: Information regarding public funding This template shall not be altered. It shall be completed without modifying/adding headings or logo, format or font. 1 TITLE OF THE MICRO-PROGRAMME:_GS1247 – Improved Kitchen Regimes Multi Country PoA SECTION A. General description of micro-programme activity (VPA) A.1. Title of the micro-scale VPA: GS1247 Improved Kitchen Regimes Multi-Country PoA GS2479 Otuke District Borehole Project 28/05/2015 Version 7 A.2. Description of the micro-scale VPA: The Micro-Scale Voluntary Project Activity 3 Otuke District is eligible under the Gold Standard methodology Technologies and Practices to Displace Decentralized Thermal Energy Consumption Version 1. The project will support the provision of safe water using borehole technology to hundreds of households within the district. By providing safe water, the project will ensure that households consume less firewood during the process of water purification and as a result there shall be a reduction of carbon dioxide emissions from the combustion process. Otuke is a largely rural area where local people typically use wood fuel on inefficient three stone fires to purify their drinking, cleaning and washing water. This process results in the release of greenhouse gas emissions from the combustion of wood - this can be avoided if a technology that does not require fuel (wood or fossil) supplies clean water desired by households. -

Post-Conflict Development in Northern Uganda: the Importance of Holistically Addressing Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2013 Post-conflict Development in Northern Uganda: The Importance of Holistically Addressing Sexual and Gender-based Violence Hannah E. Durick [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Durick, Hannah E., "Post-conflict Development in Northern Uganda: The Importance of Holistically Addressing Sexual and Gender-based Violence" (2013). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1603 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Post-Conflict Development IN Northern Uganda photo by author The Importance of Holistically Addressing Sexual and Gender-based Violence Hannah Elizabeth Durick Hannah Elizabeth Durick * 2013 * University of Tennessee Post-Conflict Development in Northern Uganda The Importance of Holistically Addressing Sexual and Gender-based Violence -

Statistical Abstract 2018

---------------------------------------------------- < The Republic of Uganda MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT Ministry of Local Government, Plot 1, Pilkington Road, Worker’s House P.O. Box 7037, Kampala (U) Tel: +256-414-256533 Email:[email protected]; Website:http://molg.go.ug December 2018 Ministry of Local Government (MoLG) Statistical Abstract 2018 Statistical Abstract Ministry of Local Government December 2018 i Ministry of Local Government (MoLG) Statistical Abstract 2018 Districts of Uganda ii Ministry of Local Government (MoLG) Statistical Abstract 2018 Foreword Hon. Col. Tom Butime Minister of Local Government The Mandate of the Ministry of Local Government is to guide, harmonize, mentor and advocate for all Local Governments in support of Government’s vision of bringing about socio-economic transformation of the country. The Ministry is responsible for mentoring, compliance inspection and support supervision of Local Governments. In order to fulfil this mandate, quality statistics are required to measure development outcomes, identify development issues, inform policy formulation, and facilitate planning, decision making, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the impact of development programmes in the LGs. It is on this basis that the Ministry of Local Government, with support from Uganda Bureau of Statistics, adopted a strategic approach towards managing data and statistics of the Ministry. This necessitated development and implementation of a five year Strategic Plan for Statistics (SPS) covering the period 2015/16 – 2019/20 to act as a building block for the Plan for National Statistical Development (PNSD) framework. The plan is aimed at enhancing data quality and use and comprehensiveness of statistics produced by the ministry. In line with the MoLG-SPS, the Ministry is required to produce an Annual Statistical abstract.The MoLG Statistical Abstract 2018 consolidates data relating to its various output indicators.