Genetics of Insect Resistance to Plant Defence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

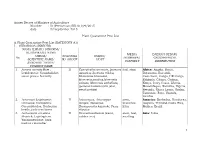

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

(Cruciferae) – Mustard Family

BRASSICACEAE (CRUCIFERAE) – MUSTARD FAMILY Plant: herbs mostly, annual to perennial, sometimes shrubs; sap sometimes peppery Stem: Root: Leaves: mostly simple but sometimes pinnately divided; alternate, rarely opposite or whorled; no stipules Flowers: mostly perfect, mostly regular (actinomorphic); 4 sepals, 4 petals often forming a cross; 6 stamens with usually 2 outer ones shorter than the inner 4; ovary superior, mostly 2 fused carpels, 1 to many ovules, 1 pistil Fruit: seed pods, often used in classification, many are slender and long (Silique), some broad (Silicle) – see morphology slide Other: a large family, many garden plants such as turnip, radish, and cabbage, also some spices; often termed the Cruciferae family; Dicotyledons Group Genera: 350+ genera; 40+ locally WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive Flower Morphology in the Brassicaceae (Mustard Family) - flower with 4 sepals, 4 petals (often like a cross, sometimes split or lobed), commonly small, often white or yellow, distinctive fruiting structures often important for ID 2 types of fruiting pods: in addition, fruits may be circular, flattened or angled in cross-section Silicle - (usually <2.5x long as wide), 2-valved with septum (replum) Silique - (usually >2.5x long as wide), 2- valved with septum (replum) Flowers, Many Genera BRASSICACEAE (CRUCIFERAE) – MUSTARD FAMILY Sanddune [Western] Wallflower; Erysimum capitatum (Douglas ex Hook.) Greene var. capitatum Wormseed Wallflower [Mustard]; Erysimum cheiranthoides L. (Introduced) Spreading Wallflower [Treacle Mustard]; Erysimum repandum L. (Introduced) Dame’s Rocket [Dame’s Violet]; Hesperis matronalis L. (Introduced) Purple [Violet] Rocket; Iodanthus pinnatifidus (Michx.) Steud. Michaux's Gladecress; Leavenworthia uniflora (Michx.) Britton [Cow; Field] Cress [Peppergrass]; Lepidium campestre L.) Ait. -

(Last Updated: 8 January 2021) List of the Plants Subject to Specific

(Annex4) (Last updated: 8 January 2021) List of the plants subject to specific phytosanitary measures to be carried out in exporting countries (Annexed table 2-2 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Plant Protection Act) and the details of requirements for each of the quarantine pests: Note: Underlined regions/countries, plants, quarantine pests or requirements will be added. Strikethrough regions/countries or plants will be deleted. Common requirements The plants must be accompanied by a phytosanitary certificate or a certified copy of the phytosanitary certificate issued by the NPPO of an exporting country to certify that the plants have been inspected and are considered to be free from quarantine pests. Item Region/countries Plants Quarantine pests Requirements No 1 [Latin America] Argentina, Uruguay, Fresh fruits of the following plants: Anastrepha fraterculus The plants must fulfill either of the following specific requirement under Ecuador, El Salvador, Guyana, Pouteria obovata, abiu (Pouteria caimito), apricot (South American fruit fly) the supervision of the NPPO of the exporting country and found to be Guatemala, Costa Rica, Colombia, (Prunus armeniaca), yellow pitahaya free from Anastrepha fraterculus. Surinam, Trinidad and Tobago, (Hylocereus megalanthus (syn. Selenicereus The additional declaration and the details of treatment (e.g. registration Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, megalanthus)), common fig (Ficus carica), number of facility, date, temperature, time) are made on the Brazil, French Guiana, Venezuela, persimmon (Diospyros), Campomanesia phytosanitary certificate or the certified copy of the phytosanitary Belize, Peru, Bolivia, Honduras, xanthocarpa, kiwi fruit (Actinidia deliciosa, A. certificate based on the work plan. Mexico chinensis)), passion fruit (Passiflora edulis), Chrysophyllum gonocarpum, tamarillo The work plan which describes the following specific requirements (Cyphomandra betacea (syn. -

Millichope Park and Estate Invertebrate Survey 2020

Millichope Park and Estate Invertebrate survey 2020 (Coleoptera, Diptera and Aculeate Hymenoptera) Nigel Jones & Dr. Caroline Uff Shropshire Entomology Services CONTENTS Summary 3 Introduction ……………………………………………………….. 3 Methodology …………………………………………………….. 4 Results ………………………………………………………………. 5 Coleoptera – Beeetles 5 Method ……………………………………………………………. 6 Results ……………………………………………………………. 6 Analysis of saproxylic Coleoptera ……………………. 7 Conclusion ………………………………………………………. 8 Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera – true flies, bees, wasps ants 8 Diptera 8 Method …………………………………………………………… 9 Results ……………………………………………………………. 9 Aculeate Hymenoptera 9 Method …………………………………………………………… 9 Results …………………………………………………………….. 9 Analysis of Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera … 10 Conclusion Diptera and aculeate Hymenoptera .. 11 Other species ……………………………………………………. 12 Wetland fauna ………………………………………………….. 12 Table 2 Key Coleoptera species ………………………… 13 Table 3 Key Diptera species ……………………………… 18 Table 4 Key aculeate Hymenoptera species ……… 21 Bibliography and references 22 Appendix 1 Conservation designations …………….. 24 Appendix 2 ………………………………………………………… 25 2 SUMMARY During 2020, 811 invertebrate species (mainly beetles, true-flies, bees, wasps and ants) were recorded from Millichope Park and a small area of adjoining arable estate. The park’s saproxylic beetle fauna, associated with dead wood and veteran trees, can be considered as nationally important. True flies associated with decaying wood add further significant species to the site’s saproxylic fauna. There is also a strong -

The Biology of Casmara Subagronoma (Lepidoptera

insects Article The Biology of Casmara subagronoma (Lepidoptera: Oecophoridae), a Stem-Boring Moth of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Myrtaceae): Descriptions of the Previously Unknown Adult Female and Immature Stages, and Its Potential as a Biological Control Candidate Susan A. Wineriter-Wright 1, Melissa C. Smith 1,* , Mark A. Metz 2 , Jeffrey R. Makinson 3 , Bradley T. Brown 3, Matthew F. Purcell 3, Kane L. Barr 4 and Paul D. Pratt 5 1 USDA-ARS Invasive Plant Research Laboratory, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314, USA; [email protected] 2 USDA-ARS Systematic Entomology Lab, Beltsville, MD 20013-7012, USA; [email protected] 3 USDA-ARS Australian Biological Control Laboratory, CSIRO Health and Biosecurity, Dutton Park QLD 4102, Australia; jeff[email protected] (J.R.M.); [email protected] (B.T.B.); [email protected] (M.F.P.) 4 USDA-ARS Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology, Gainesville, FL 32608, USA; [email protected] 5 USDA-ARS, Western Regional Research Center, Invasive Species and Pollinator Health Research Unit, 800 Buchanan Street, Albany, CA 94710, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-954-475-6549 Received: 27 August 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 23 September 2020 Simple Summary: Rhodomyrtus tomentosa is a perennial woody shrub throughout Southeast Asia. Due to its prolific flower and fruit production, it was introduced into subtropical areas such as Florida and Hawai’i, where it is now naturalized and invasive. In an effort to find sustainable means to control R. tomentosa, a large-scale survey was mounted for biological control organisms. -

The Life History and Management of Phyllotreta Cruciferae and Phyllotreta Striolata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), Pests of Brassicas in the Northeastern United States

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2004 The life history and management of Phyllotreta cruciferae and Phyllotreta striolata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), pests of brassicas in the northeastern United States. Caryn L. Andersen University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Andersen, Caryn L., "The life history and management of Phyllotreta cruciferae and Phyllotreta striolata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), pests of brassicas in the northeastern United States." (2004). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 3091. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/3091 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LIFE HISTORY AND MANAGEMENT OF PHYLLOTRETA CRUCIFERAE AND PHYLLOTRETA STRIOLATA (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE), PESTS OF BRASSICAS IN THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Thesis Presented by CARYN L. ANDERSEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE September 2004 Entomology © Copyright by Caryn L. Andersen 2004 All Rights Reserved THE LIFE HISTORY AND MANAGEMENT OF PHYLLOTRETA CRUCIFERAE AND PHYLLOTRETA STRIOLATA (COLEOPTERA: CHRYSOMELIDAE), PESTS OF BRASSICAS IN THE NORTHEASTERN UNITED STATES A Thesis Presented by CARYN L. ANDERSEN Approved as to style and content by: Tt, Francis X. Mangan, Member Plant, Soil, and Insect Sciences DEDICATION To my family and friends. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisors, Roy Van Driesche and Ruth Hazzard, for their continual support, encouragement and thoughtful advice. -

Landscape Dynamics Determine the Small-Scale Genetic Structure of An

Journal of Coastal Research 28 4 780–786 West Palm Beach, Florida July 2012 Landscape Dynamics Determine the Small-Scale Genetic Structure of an Endangered Dune Slack Plant Species Dries Bonte{, Peter Breyne{, Rein Brys{{, Eduardo de la Pen˜a{, Bram D’hondt{, Ce´line Ghyselen{, Martijn L. Vandegehuchte{, and Maurice Hoffmann{{ www.cerf-jcr.org {Ghent University {Research Institute for Nature and Forest Department of Biology Department of Biodiversity and Natural Environment Terrestrial Ecology Unit Kliniekstraat 25 K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35 1070 Brussel, Belgium 9000 Ghent, Belgium [email protected] ABSTRACT Bonte, D.; Breyne, P.; Brys, R.; de la Pen˜ a, E.; D’hondt, B.; Ghyselen, C.; Vandegehuchte, M.L., and Hoffmann, M., 2012. Landscape dynamics determine the small-scale genetic structure of an endangered dune slack plant species. Journal of Coastal Research, 28(4), 780–786. West Palm Beach (Florida), ISSN 0749-0208. Understanding the processes that determine genetic variation within landscapes is a crucial factor for successful management of threatened plant species that are sensitive to both environmental and genetic bottlenecks. While current insights point to the importance of historical landscape processes for the genetic structure of populations at large spatial scales, their relevance at small spatial scales has been largely neglected. In this context, coastal dunes are a typical example of dynamic and geologically young landscapes in which current and historical sand drift may have strong impacts on the spatial dynamics of a large number of plant species. One of these is the endangered plant species Parnassia palustris, typically inhabiting dune slacks formed by recent sand displacements in parabolic dune landscapes. -

Determination of Genetic Diversity of Some Species of Brassicaceae Using SDS-PAGE of Seed Protein and ISSR Markers

20 Egypt. J. Bot., Vol. 55, No.2 pp. 307- 318 (2015) Determination of Genetic Diversity of Some Species of Brassicaceae Using SDS-PAGE of Seed Protein and ISSR Markers Nelly M. George Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Zagazig University, 44519 Egypt VALUATION of genetic diversity among 10 species of E Brassicaceae have been performed based on variations in seed protein electrophoretic patterns as revealed by SDS-PAGE and ISSR analyses, separately and in combination. The maximum genetic similarity was observed between Brassica nigra and B. rapa, while the lowest genetic similarity was observed between B. nigra and Sisymbrium irrio. Cluster analysis generated a dendrogram that separated the studied taxa in two main clusters; the five species of tribe Brassiceae were grouped close to each other in one cluster with Sisymbrium irrio. The remaining studied species; Capsella bursa- pastoris, Erysimum cheiranthoides, Mathiola longipetale and Thlaspi arvense, were grouped in a second cluster. Keywords: Brassicaceae, SDS-PAGE, ISSR, Genetic diversity. The Brassicaceae (Cruciferae or mustard family) includes several crop plants grown worldwide, some of which have been cultivated since prehistoric times. Various species are grown for oil, mustard condiment, fodder and forage for animals, or as vegetables (Crisp, 1976 and Simmonds, 1986). Several classification systems were proposed from the early 19th to the mid 20th century. According to these systems, the Brassicaceae divided into anywhere from 4 to 19 tribes and 20 to 30 sub-tribes (Schulz, 1936 and Janchen, 1942). Mark et al. (2006) suggested that Brassicaceae includes two important model systems; the first included the Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. -

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

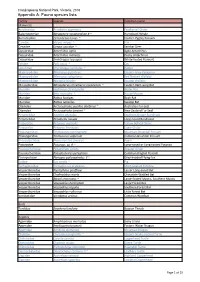

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

Erysimum Cheiranthoides (Brassicaceae) Reduces Total Cardenolide Abundance but Increases Resistance to Insect Herbivores

Journal of Chemical Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-020-01225-y Less Is More: a Mutation in the Chemical Defense Pathway of Erysimum cheiranthoides (Brassicaceae) Reduces Total Cardenolide Abundance but Increases Resistance to Insect Herbivores Mahdieh Mirzaei1 & Tobias Züst2 & Gordon C. Younkin1 & Amy P. Hastings3 & Martin L. Alani1 & Anurag A. Agrawal3 & Georg Jander1 Received: 26 April 2020 /Revised: 6 October 2020 /Accepted: 9 October 2020 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020 Abstract Erysimum cheiranthoides L (Brassicaceae; wormseed wallflower) accumulates not only glucosinolates, which are characteristic of the Brassicaceae, but also abundant and diverse cardenolides. These steroid toxins, primarily glycosylated forms of digitoxi- genin, cannogenol, and strophanthidin, inhibit the function of essential Na+/K+-ATPases in animal cells. We screened a popu- lation of 659 ethylmethanesulfonate-mutagenized E. cheiranthoides plants to identify isolates with altered cardenolide profiles. One mutant line exhibited 66% lower cardenolide content, resulting from greatly decreased cannogenol and strophanthidin glycosides, partially compensated for by increases in digitoxigenin glycosides. This phenotype was likely caused by a single- locus recessive mutation, as evidenced by a wildtype phenotype of F1 plants from a backcross, a 3:1 wildtype:mutant segregation in the F2 generation, and genetic mapping of the altered cardenolide phenotype to one position in the genome. The mutation created a more even cardenolide distribution, decreased the average cardenolide polarity, but did not impact most glucosinolates. Growth of generalist herbivores from two feeding guilds, Myzus persicae Sulzer (Hemiptera: Aphididae; green peach aphid) and Trichoplusia ni Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae; cabbage looper), was decreased on the mutant line compared to wildtype. -

OLFS Plant List

Checklist of Vascular Plants of Oak Lake Field Station Compiled by Gary E. Larson, Department of Natural Resource Management Trees/shrubs/woody vines Aceraceae Boxelder Acer negundo Anacardiaceae Smooth sumac Rhus glabra Rydberg poison ivy Toxicodendron rydbergii Caprifoliaceae Tatarian hone ysuckle Lonicera tatarica* Elderberry Sambucus canadensis Western snowberry Symphoricarpos occidentalis Celastraceae American bittersweet Celastrus scandens Cornaceae Redosier dogwood Cornus sericea Cupressaceae Eastern red cedar Juniperus virginiana Elaeagnaceae Russian olive Elaeagnus angustifolia* Buffaloberry Shepherdia argentea* Fabaceae Leadplant Amorpha canescens False indigo Amorpha fruticosa Siberian peashrub Caragana arborescens* Honey locust Gleditsia triacanthos* Fagaceae Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Grossulariaceae Black currant Ribes americanum Missouri gooseberry Ribes missouriense Hippocastanaceae Ohio buckeye Aesculus glabra* Oleaceae Green ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica Pinaceae Norway spruce Picea abies* White spruce Picea glauca* Ponderosa pine Pinus ponderosa* Rhamnaceae Common buckthorn Rhamnus cathartica* Rosaceae Serviceberry Amelanchier alnifolia Wild plum Prunus americana Hawthorn Crataegus succulenta Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Siberian crab Pyrus baccata* Prairie rose Rosa arkansana Black raspberry Rubus occidentalis Salicaceae Cottonwood Populus deltoides Balm-of-Gilead Populus X jackii* White willow Salix alba* Peachleaf willow Salix amygdaloides Sandbar willow Salix exigua Solanaceae Matrimony vine Lycium barbarum* Ulmaceae -

Citation: Badenes-Pérez, F. R. 2019. Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order 2 Brassicales

1 Citation: Badenes-Pérez, F. R. 2019. Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order 2 Brassicales. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 112: 318-329. 3 https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/say043 4 5 6 Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order Brassicales 7 Francisco Rubén Badenes-Perez 8 Instituto de Ciencias Agrarias, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 28006 9 Madrid, Spain 10 E-mail: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 ABSTRACT This paper reviews the most important cases of trap crops and insectary 26 plants in the order Brassicales. Most trap crops in the order Brassicales target insects that 27 are specialist in plants belonging to this order, such as the diamondback moth, Plutella 28 xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), the pollen beetle, Meligethes aeneus Fabricius 29 (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), and flea beetles inthe genera Phyllotreta Psylliodes 30 (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). In most cases, the mode of action of these trap crops is the 31 preferential attraction of the insect pest for the trap crop located next to the main crop. 32 With one exception, these trap crops in the order Brassicales have been used with 33 brassicaceous crops. Insectary plants in the order Brassicales attract a wide variety of 34 natural enemies, but most studies focus on their effect on aphidofagous hoverflies and 35 parasitoids. The parasitoids benefiting from insectary plants in the order Brassicales 36 target insects pests ranging from specialists, such as P. xylostella, to highly polyfagous, 37 such as the stink bugs Euschistus conspersus Uhler and Thyanta pallidovirens Stål 38 (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae).