Women and Education in India-A Representative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Study Report

Presidency University Self-Study RepoRt For Submission to the National Assessment and Accreditation Council Presidency University Kolkata 2016 (www.presiuniv.ac.in) Volume-3 Self-Study Report (Volume-3) Departmental Inputs 1 Faculty of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Self-Study RepoRt For Submission to the National Assessment and Accreditation Council Presidency University Kolkata 2016 (www.presiuniv.ac.in) Volume-3 Departmental Inputs Faculty of Natural and Mathematical Sciences Table of Contents Volume-3 Departmental Inputs Faculty of Natural and Mathematical Sciences 1. Biological Sciences 1 2. Chemistry 52 3. Economics 96 4. Geography 199 5. Geology 144 6. Mathematics 178 7. Physics 193 8. Statistics 218 Presidency University Evaluative Report of the Department : Biological Sciences 1. Name of the Department : Biological Sciences 2. Year of establishment : 2013 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the university? Faculty of Natural and Mathematical Sciences 4. Names of programmes offered (UG, PG, M.Phil., Ph.D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : B.Sc (Hons) in Biological Sciences, M.sc. in Biological Sciences, PhD. 5. Interdisciplinary programmes and de partments involved: ● The Biological Sciences Department is an interdisciplinary department created by merging the Botany, Zoology and Physiology of the erstwhile Presidency College. The newly introduced UG (Hons) and PG degree courses Biological Sciences cut across the disciplines of life science and also amalgamated the elements of Biochemistry, Statistics and Physics in the curricula. ● The UG elective General Education or ‘GenEd’ programmes, replace the earlier system of taking ‘pass course’ subjects and introduce students to a broad range of topics from across the disiplines. -

Women in India's Freedom Struggle

WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE When the history of India's figf^^M independence would be written, the sacrifices made by the women of India will occupy the foremost plofe. —^Mahatma Gandhi WOMEN IN INDIA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE MANMOHAN KAUR IVISU LIBBARV STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED .>».A ^ STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016 Women in India's Freedom Strug^e ©1992, Manmohan Kaur First Edition: 1968 Second Edition: 1985 Third Edition: 1992 ISBN 81 207 1399 0 -4""D^/i- All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. PRINTED IN INDIA Published by S.K. Ghai, Managing Director, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., L-10, Green Park Extension, New Delhi-110016. Laserset at Vikas Compographics, A-1/2S6 Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi-110029. Printed at Elegant Printers. New Delhi. PREFACE This subject was chosen with a view to recording the work done by women in various phases of the freedom struggle from 1857 to 1947. In the course of my study I found that women of India, when given an opportunity, did not lag behind in any field, whether political, administrative or educational. The book covers a period of ninety years. It begins with 1857 when the first attempt for freedom was made, and ends with 1947 when India attained independence. While selecting this topic I could not foresee the difficulties which subsequently had to be encountered in the way of collecting material. -

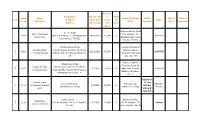

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist a Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd

2018 Heritage Vol.-V Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist A Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd. Associate Professor, Dept. of Political Science, Bethune College, Kolkata-6 Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore, although basically a poet, had a multifaceted personality. Among his various activities his sincerity as a social thinker and activist attract our attention. But this area is till now comparatively unexplored. Many scholars in this area have tried to study Tagore as a social thinker. But so far the findings are scattered and on the whole there is no comprehensive analysis in the strict sense of the term. Hence it is necessary to collect the different findings and to integrate and arrange them within a theoretical framework. This article is an attempt to make a review of literature of the existing books and to prepare a short but sharp bibliography to introduce the area. Key words: Rabindranath Tagore, society, social, political, history, education, Santiniketan, Visva-Bharati Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941) was a prolific writer, a successful music composer, a painter, an actor, a drama director and what not. Besides these talents, he was also a social activist and contributed a lot to Indian social and political thought, although this area has not been very much explored till now. Tagore was emphatic upon society building. So he tried to develop all the component elements which were essential for developing the Indian society. He studied the history of India to follow the trend of its evolution. Next he prepared his programme of action – rural reconstruction and spread of education. -

Theme: Evolving Humanity, Emerging Worlds Panel Title

1 Theme: Evolving Humanity, Emerging Worlds Panel Title: Food and Environmental Security: the imperatives of indigenous knowledge systems Panel Reference: PE03 FOOD PROCESSING BY RAJBANSHI INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF NORTH BENGAL, INDIA Ashok Das Gupta University of North Bengal [email protected] Short Abstract Food Processing by Rajbanshi Indigenous People of North Bengal, India Author: Ashok Das Gupta (University of North Bengal) Mail All Authors: [email protected] Short Abstract This paper is going to focus on Food Processing by Rajbanshi Indigenous People of North Bengal, India. Long Abstract Rajbanshi social fold comprising of both caste and communities constitute 18% of total population of North Bengal, India. They are in favour of irrigation (small and broad scale), sacred grove, fencing and lattice, highland and marshland, river basins and valleys, kitchen 2 garden, etc. They are too good with the complex production systems of crops, cereals, vegetables, rapeseeds, honey, bamboo, liquor and sugar yielding varieties, medicinal herbs, fruits, mushrooms, lichen, livestock, fish, crab, small fish, mud fish, prawn as well as fiber, silk, silk cotton, drinks, areca, betel and tobacco. They are fond of meat, milk, egg and fish. These flora and fauna are again source of fuel, fodder, natural dye, and pesticides. Rajbanshis is traditional life used to go through barter and reciprocity. Women are involved in preserving fish, paddy, fruit and milk items. In fish and paddy preservation, they use arum. Fruits are preserved in dried or as pickles. They do not waste their organic waste and use them as manure associated with ash, light trap, food-web and natural insecticides. -

Title: Women of Agency: the Penned Thoughts of Bengali Muslim

Title: Women of Agency: The Penned Thoughts of Bengali Muslim Women Writers of 9th 20th the Late 1 and Early Century Submitted by: Irteza Binte-Farid In Fulfillment of the Feminist Studies Honors Program Date: June 3, 2013 introduction: With the prolusion of postcolornal literature and theory arising since the 1 9$Os. unearthing subaltern voices has become an admirable task that many respected scholars have undertaken. Especially in regards to South Asia, there has been a series of meticulouslyresearched and nuanced arguments about the role of the subaltern in contributing to the major annals of history that had previously been unrecorded, greatly enriching the study of the history of colonialism and imperialism in South Asia. 20th The case of Bengali Muslim women in India in the late l91 and early century has also proven to be a topic that has produced a great deal of recent literature. With a history of scholarly 19th texts, unearthing the voices of Hindu Bengali middle-class women of late and early 2O’ century, scholars felt that there was a lack of representation of the voices of Muslim Bengali middle-class women of the same time period. In order to counter the overwhelming invisibility of Muslim Bengali women in academic scholarship, scholars, such as Sonia Nishat Amin, tackled the difficult task of presenting the view of Muslim Bengali women. Not only do these new works fill the void of representing an entire community. they also break the persistent representation of Muslim women as ‘backward,’ within normative historical accounts by giving voice to their own views about education, religion, and society) However, any attempt to make ‘invisible’ histories ‘visible’ falls into a few difficulties. -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

2021 Banerjee Ankita 145189

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Santiniketan ashram as Rabindranath Tagore’s politics Banerjee, Ankita Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 THE SANTINIKETAN ashram As Rabindranath Tagore’s PoliTics Ankita Banerjee King’s College London 2020 This thesis is submitted to King’s College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy List of Illustrations Table 1: No of Essays written per year between 1892 and 1936. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal

DANIELA CAPPELLO | 1 Comics and Science Fiction in West Bengal Daniela Cappello Abstract: In this paper I look at four examples of Bengali SF (science fiction) comics by two great authors and illustrators of sequential art: Mayukh Chaudhuri (Yātrī, Smārak) and Narayan Debnath (Ḍrāgoner thābā, Ajānā deśe). Departing from a con- ventional understanding of SF as a fixed genre, I aim at showing that the SF comic is a ‘mode’ rather than a ‘genre’, building on a very fluid notion of boundaries between narrative styles, themes, and tropes formally associated with fixed genres. In these Bengali comics, it is especially the visual space of the comic that allows for blending and ‘contamination’ with other typical features drawn from adventure and detective fiction. Moreover, a dominant thematic thread that cross-cuts the narratives here examined are the tropes of the ‘other’ and the ‘unknown’, which are in fact central images of both adventure and SF: the exploration and encounter with ‘unknown’ (ajānā) worlds and ‘strange’ species (adbhut jāti) is mirrored in the usage of a lan- guage that expresses ‘otherness’ and strangeness. These examples show that the medium of the comic framing the SF story adds further possibilities of reading ‘genre hybridity’ as constitutive of the genre of SF as such. WHAT’S IN A COMIC? Before addressing SF comics in West Bengal, I will first look at some interna- tional definitions of comic to outline the main problematics that have been raised in the literature on this subject. In one of the first books introducing the world of comics to artists and academics, Will Eisner looks at the me- chanics of ‘sequential art’ (a term coined by Eisner himself) describing it as a dual ‘form of reading’ (Eisner 1985: 8): The format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills. -

August 2020 Kolkata

Rs.10 JJ II MM AA Volume 64 (RNI) Number 08 AUGUST 2020 KOLKATA Official Publication of the Indian Medical Association INDEX COPERNICUS I N T E R N A T I O N A L Volume 118 (JIMA) s Number 08 s August 2020 s KOLKATA ISSN 0019-5847 Dr 9911ST C Visit us at https: // onlinejima.com 01 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, VOL 118, NO 08, AUGUST 2020 02 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, VOL 118, NO 08, AUGUST 2020 03 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, VOL 118, NO 08, AUGUST 2020 04 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, VOL 118, NO 08, AUGUST 2020 05 JOURNAL OF THE INDIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, VOL 118, NO 08, AUGUST 2020 ELECTED OFFICE BEARERS OF IMA HQs. & VARIOUS WINGS National President IMA College of General Practitioners Journal of IMA Dr. Rajan Sharma (Haryana) Dean of Studies Honorary Editor Hony. Secretary General Dr. Hiranmay Adhikary (Assam) Dr. Jyotirmoy Pal (Bengal) Dr. R.V. Asokan Vice Dean Honorary Associate Editors Immediate Past National President Dr. Sachchidanand Kumar (Bihar) Dr. Sibabrata Banerjee (Bengal) Dr. Santanu Sen (Bengal) Dr. Sujoy Ghosh (Bengal) Honorary Secretary Dr. L. Yesodha (Tamil Nadu) National Vice-Presidents Honorary Secretary Dr. D. D. Choudhury (Uttaranchal) Honorary Joint Secretaries Dr. Sanjoy Banerjee (Bengal) Dr. Atul D. Pandya (Gujarat) Dr. C. Anbarasu (Tamil Nadu) Dr. T. Narasinga Reddy (Telangana) Dr. R. Palaniswamy (Tamil Nadu) Honorary Assistant Secretary Dr. G. N. Prabhakara (Karnataka) Dr. Ashok Tripathi (Chhattisgarh) Dr. Shilpa Basu Roy (Bengal) Dr. Fariyad Mohammed (Rajasthan) Honorary Finance Secretary Dr. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita