Pinball Kids: Preventing School Exclusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

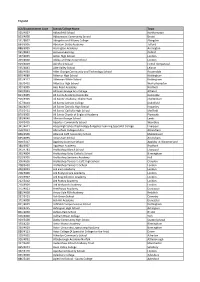

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

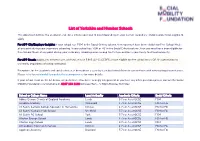

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Working Together to Tackle Climate Change ‘You’Re Never Too Young to Make a Difference’ Youth Voice Summit: 12Th February 2020

Appendix 1 Working together to tackle Climate Change ‘You’re never too young to make a difference’ Youth Voice Summit: 12th February 2020 Summary Event Report 1 Background to the event Since 2016, the Voice, Influence and Change team have hosted a series of “Youth Voice Summit” events for young people in Leeds to come together to work with local decision makers on an issue that is important to them. For 2020, the theme was “Tackling Climate Change”. This was to reflect: 1. Young People across the country voting “Tackling Climate Change” as their top issue in the 2019 annual UK Youth Parliament “Make Your Mark” ballot 2. Leeds City Council formally declaring a ‘climate emergency’ in March 2019 3. The growing youth-led “Strike4Climate” movement in cities around the world, including here in Leeds The Voice, Influence and Change Team worked in partnership with the Leeds City Council Health and Wellbeing Service to plan and deliver the event. The day was split into three sequential workshops that were designed to enable students to consider climate change from a broad philosophical perspective before having the opportunity to take part in a Q&A panel and then finally working together to devise and develop practical solutions to lower the carbon footprint of their school communities. Their solutions are to be used in Leeds City Council guidance that will be issued to schools. Consultation and marketplace stalls Having such a large and diverse range of young people in one place provided a great opportunity for other services to deliver their own consultation and engagement work during the break times. -

Report Author: Elizabeth Richards Tel: 87235 Report of Director of Children and Families Report to Executive Board Date: 24 June

Report author: Elizabeth Richards Tel: 87235 Report of Director of Children and Families Report to Executive Board Date: 24 June 2020 Subject: Outcome of consultation and request to approve funding to permanently increase learning places at Leeds West Academy from September 2022 Are specific electoral wards affected? Yes No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): Bramley & Stanningley Has consultation been carried out? Yes No Are there implications for equality and diversity and cohesion and Yes No integration? Will the decision be open for call-in? Yes No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? Yes No If relevant, access to information procedure rule number: Appendix number: Summary 1. Main issues This report contains details of a proposal brought forward by The White Rose Academies Trustees, working in partnership with Leeds City Council, to meet the local authority’s duty to ensure sufficiency of school places. The changes that are proposed form prescribed alterations under Department for Education advice for academy trusts, Making Significant Changes to an Open Academy (November 2019). For prescribed alterations for maintained schools the Local Authority would be the decision maker, but for expansions relating to Academies the Trust Board is the decision maker with regards to the proposal. However, as the scheme is being funded by the Local Authority, Executive Board would need to grant provisional approval for authority to spend (ATS) to deliver the proposed permanent expansion at Leeds West Academy. A consultation on a proposal to expand Leeds West Academy from a capacity of 1200 to 1500 students by increasing the admission number in year 7 from 240 to 300 with effect from September 2022 took place between 27 January and 1 March 2020. -

Morley Academy / Farnley Academy / Bruntcliffe Academy / Cockburn School and Swallow Hill Results Day and Enrolment Thursday 23 August 2018

Morley Academy / Farnley Academy / Bruntcliffe Academy / Cockburn School and Swallow Hill Results Day and Enrolment Thursday 23 August 2018 Enrolment will take place in your school. Collect your GCSE results and take them to the enrolment desk If your results are as expected and there are no changes to your course choices You will be enrolled and invited to Induction on Wednesday 5 September 2018, you will be allocated a time when you collect your results and enrol. You will need your Data Collection Sheet, Biometric and Photograph Authorisation letter and Projects. If your results are as expected but you want to change your course choices We will be unable to confirm amendments to course choices until enrolment for all students closes at 3.00pm on Friday 24 August 2018. Please speak to a member of staff to tell them your new choices and contact details. A member of staff will contact you on Tuesday 28 August 2018 to confirm your change or to invite you in for a further discussion regarding you choices. Once your curriculum is confirmed you will be enrolled and invited to Induction on Wednesday 5 September 2018. If your results are not as expected Please speak to a member of the Elliott Hudson team at the enrolment desk. You will be invited to Enrolment Clearing on Friday 24 August between 9.00 and 2.00pm at where advice and guidance will be available. Chief Executive Officer: Sir John Townsley BA (Hons) NPQH Executive Principal: Post 16 Education: Mr D Holtham BSc (Hons) Chair of Governors: Mr Terry Elliot OBE, JP, BA (Hons) July 2018 Dear Student Many thanks for attending one of our taster events in the summer term; it was fantastic to see so many applicants keen to join Elliott Hudson College. -

Doing School” and “Having Fun”: Tensions Between Family and School Conceptions of Education

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Doing School” and “Having Fun”: Tensions between Family and School Conceptions of Education A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Charlene Catherine Bredder Committee in Charge: Hugh B. Mehan, Chair Jeff Haydu Paula Levin Christena Turner Olga Vasquez 2006 Copyright Charlene Catherine Bredder, 2006 All rights reserved The dissertation of Charlene Catherine Bredder is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION To all parents and teachers who strive to create the best educational experiences for their students. It is the toughest job in the world to raise a child. This dissertation is dedicated to all people who contribute to positive experiences for students. It is through our efforts that we grow. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ……………………………………………............ iii Dedication ………………………………………………………... iv Table of Contents ………………………………………………… v Acknowledgements ……………………………………………… vi Vita, Publications, and Fields of Study ………………………….. x Abstract ………………………………………………………….. xi Chapter 1: Understanding Homeschool Programs ………………. 1 Chapter 2: The Role of School in Society ……………………….. 29 Chapter 3: -

Engagement: an Indigenous Community's Fight for Educational Equity and Cultural Reclamation in a New England School District

Family-School-Community (Dis)Engagement: An Indigenous Community's Fight for Educational Equity and Cultural Reclamation in a New England School District Author: Shaneé Adrienne Washington Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108518 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). Boston College Lynch School of Education Department of Teacher Education, Special Education, and Curriculum and Instruction Curriculum and Instruction Doctoral Program FAMILY-SCHOOL-COMMUNITY (DIS)ENGAGEMENT: AN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY’S FIGHT FOR EDUCATIONAL EQUITY AND CULTURAL RECLAMATION IN A NEW ENGLAND SCHOOL DISTRICT Dissertation by SHANEÉ ADRIENNE WASHINGTON submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 © Copyright by Shaneé Adrienne Washington 2019 Abstract Family-School-Community (Dis)Engagement: An Indigenous Community’s Fight for Educational Equity and Cultural Reclamation in a New England School District Shaneé Adrienne Washington Dr. Lauri Johnson, Chair This exploratory case study examined family-school-community engagement in a small New England school district and town that is home to a federally recognized Indigenous Tribe that has inhabited the area for 12,000 years and whose children represent the largest group of racially minoritized students in the public schools. Using Indigenous protocols and methodologies that included relational accountability, individual semi-structured conversations, talking circles, and participant observation, this study explored the ways that Indigenous families and community members as well as district educators conceptualized and practiced family-school-community engagement and whether or not their conceptualizations and practices were aligned and culturally sustaining/revitalizing. -

The Progressive Class Holistic Learning Model & Family School Partnership

1 Deakin University Faculty of Arts and Education School of Education Research Paper Title: THE PROGRESSIVE CLASS HOLISTIC LEARNING MODEL & FAMILY SCHOOL PARTNERSHIP AT GREENVALE PRIMARY SCHOOL 2003-2009 Candidate Name ANDREW KOHANE Degree: MASTER OF EDUCATION E700 Andrew Kohane 2 B.A., (Melbourne University) Dip Ed (James Cook University) Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education. September, 2011. Student ID No: 2000196107 Address 23 Waldemar Rd, Heidelberg, Victoria, 3084. Supervisor: Jennifer Angwin Examiner: CANDIDATE'S STATEMENT I certify that the Research Paper entitled: THE PROGRESSIVE CLASS: HOLISTIC LEARNING MODEL & FAMILY SCHOOL PARTNERSHIP AT GREENVALE PRIMARY SCHOOL: 2003-2009 Submitted for the degree of Masters of Education EXR 796-7 is the result of my own work, except where otherwise acknowledged, and that this Research Paper/Minor Thesis (or any part of the same) has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. There has been no requirement for Ethics approval. Signed Date 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................ 3 GLOSSARY OF TERMS ............................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Context of the Research- Development of the Progressive Class Stream .......... 7 1.2 Research Questions ................................................................................................... -

“Why Isn't It the Same As Any Other Family?”: Understanding Emergent

“Why Isn’t It the Same as Any Other Family?”: Understanding Emergent Family Narratives and Early Education Experiences Among LGBTQ+ Parents The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Matthews, Timothy Joseph. 2020. “Why Isn’t It the Same as Any Other Family?”: Understanding Emergent Family Narratives and Early Education Experiences Among LGBTQ+ Parents. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Graduate School of Education. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37364535 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! !! ! "#$%!&'()*!&*!*$+!',-+!,'!,(%!.*$+/!0,-&1%234!5(6+/'*,(6&(7!8-+/7+(*!9,-&1%! :,//,*&;+'!,(6!8,/1%!86<=,*&.(!8>?+/&+(=+'!@-.(7!ABCDEF!G,/+(*'! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'(!)%*+,'!-.&&'+/*! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0.&'+1#2+!34!52%/! -+1+6#&'!74!8%/+! 5.91.!74!:.&;<=#*+! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! >!"'+*#*!?1+*+2&+6!&%!&'[email protected]&(! %D!&'+!E1.6B.&+!5A'%%C!%D!36BA.&#%2!%D!F.1G.16!H2#G+1*#&(! !#2!?.1&#.C!@BCD#CC$+2&!%D!&'+!8+IB#1+$+2&*! D%1!&'+!J+K1++!%D!J%A&%1!%D!36BA.&#%2! ! ! ! LMLM! ! #! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! H!IJIJ! D&-.*$%!K.'+?$!L,**$+M'! @11!N&7$*'!N+'+/;+6! ! ! ! ! ##! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! =#&'!&'.2N*!D%1O!.26!#2!$+$%1(!%D!$(!,.1+2&*O!! =#CC#.$!.26!).2+O! /'%!*B,,%1&+6!$(!C#D+C%2K!IB+*&!&%!+P,C%1+!.26!&%!C+.12O!! .26!/'%*+!*+2*+!%D!+$,.&'(!&.BK'&!$+!&%!C%%N!%B&!D%1!%&'+1*Q! -

Using Families' Funds of Knowledge Literacy to Enhance Family-School Relationships" (2020)

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 2-28-2020 Using families' Funds of Knowledge literacy to enhance family- school relationships Kaitlyn Greenwood Rowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Language and Literacy Education Commons Recommended Citation Greenwood, Kaitlyn, "Using families' Funds of Knowledge literacy to enhance family-school relationships" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 2760. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2760 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING FAMILIES’ FUNDS OF KNOWLEDGE LITERACY TO ENHANCE FAMILY-SCHOOL RELATIONSHIPS by Kaitlyn Greenwood A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Language, Literacy & Sociocultural Education College of Education In partial fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Master of Arts in Reading Education at Rowan University February 29, 2020 Thesis Chair: Dr. Valarie Lee Ph.D. Dedications I would like to dedicate this thesis to my parents, Harry and Diane, and my brother, Brandon, whose love and support helped me achieve more than I thought possible. Thank you for always believing in me, encouraging me to shoot for the stars, and helping me reach my full potential. Acknowledgments I would like to thank and acknowledge my advisor, Dr. Valarie Lee, for her constant support and inspiration throughout this journey. I would also like to recognize Dr. Susan Browne and the Rowan Literacy Department for guiding me on a path to inspire change in the school community. -

Remote Desktop Redirected Printer

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 928/4007 Abbeyfield School Northampton 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 931/8007 Abingdon and Witney College Abingdon 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 209/4600 Addey and Stanhope School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange Community and Technology School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 336/5402 Aldersley High School Wolverhampton 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 357/4604 All Saints Catholic College Dukinfield 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 373/5401 All Saints' Catholic High School Sheffield 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 909/5407 Appleby Grammar School Appleby-in-Westmorland 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4781 Archbishop Blanch School Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 -

The Rediscovery of the Family and Community As Partners in Education

Educational Review, Vol. 52, No. 2, 2000 Beyond the Classroom Walls: the rediscovery of the family and community as partners in education TREVOR H. CAIRNEY, University of Western Sydney ABSTRACT Teachers have been aware of the inuence of home on school success for a long time. However, in the last decade we have seen a signicant increase in the interest of educational researchers, educational authorities and individual teachers in the relationship between home, school and community. In this paper I want to set this emerging interest in its historical context and challenge readers to consider this topic through multiple, and more diverse and appropriate lenses. I want to argue that there is a need to look closely at the nature of the relationship between home and school and to deconstruct the purposes that drive these initiatives. There is a need to examine the many claims about the relationship between home and school, and to critique the decit views that have driven much of this interest. However, rather than just to critique, I want to explore alternative more responsive models for developing partnerships between home and school, and use literacy practices as one way to illustrate some of the options available. While there has been a dramatic increase in awareness and research concerning the relationship between home and school in the last decade, the stimulus for this increased interest has its roots in education reforms of the 1960s and 1970s. Some of the most signicant early interest in the topic area occurred in the United Kingdom. The Plowden Report (Department of Education and Science, 1967) was one of a number of factors that led to a growing awareness by schools of the home and its relationship to school learning.