Voice in Communication and Relationships Among Brown Towhees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

California Towhee Responses to Chick Distress Calls

The Condor 109:79–87 # The Cooper Ornithological Society 2007 OFFSPRING DISCRIMINATION WITHOUT RECOGNITION: CALIFORNIA TOWHEE RESPONSES TO CHICK DISTRESS CALLS LAURYN BENEDICT1 Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Abstract. Accurate offspring discrimination improves parental fitness by ensuring appropriate parental investment. In colonial avian species, offspring discrimination is often mediated by recognition of individual offspring vocalizations, but spatially segregated species do not necessarily need sophisticated recognition abilities if parents can use alternative information to distinguish offspring from nonoffspring. I experimen- tally tested the hypothesis that territorial California Towhee (Pipilo crissalis) parents use a location-based decision rule, instead of true vocal recognition of offspring, when deciding whether to respond to chick distress calls. Accurate responses to offspring distress calls should be favored by natural selection because they can have large fitness benefits if parents succeed in chasing away potential nest predators. Responses to nonoffspring, in contrast, may be costly and should not be favored by natural selection. Towhee parents were presented with a series of three playback experiments in which I manipulated the identity of the vocalizing chick, the age of resident chicks, and the location of the distress call broadcast. Parents showed no evidence of individual vocal recognition and no pattern of differential response to distress calls when offspring age differed from that of the calling chick. Parents did, however, exhibit a significant tendency to approach distress calls originating near their offspring more often than distress calls originating elsewhere on their territory. These results provide support for the evolution of an offspring discrimination strategy based on a simple location-based decision rule instead of true vocal recognition. -

Southeast Arizona, USA 29Th December 2019 - 11Th January 2020

Southeast Arizona, USA 29th December 2019 - 11th January 2020 By Samuel Perfect Bird Taxonomy for this trip report follows the IOC World Bird List (v 9.2) Site info and abbreviations: Map of SE Arizona including codes for each site mentioned in the text Twin Hills Estates, Tucson (THE) 32.227400, -111.059838 The estate is by private access only. However, there is a trail (Painted Hills Trailhead) at 32.227668, - 111.038959 which offers much the same diversity in a less built up environment. The land in the surrounding area tends to be private with multiple “no trespassing” signs so much of the birding had to be confined to the road or trails. Nevertheless, the environment is largely left to nature and even the gardens incorporate the natural flora, most notably the saguaro cacti. The urban environment hosts Northern Mockingbird, Mourning Dove and House Finch in abundance whilst the trail and rural environments included desert specialities such as Cactus Wren, Phainopepla, Black-throated Sparrow and Gila Woodpecker. Saguaro National Park, Picture Rocks (SNP) 32.254136, -111.197316 Although we remained in the car for much of our visit as we completed the “Loop Drive” we did manage to soak in much of the scenery of the park set in the West Rincon Mountain District and the impressive extent of the cactus forest. Several smaller trails do border the main driving loop, so it was possible to explore further afield where we chose to stop. There is little evidence of human influence besides the roads and trails with the main exception being the visitor centre (see coordinates). -

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of SONG and RESPONSES to SONG PLAYBACK University of Colorado at Denver

FINAL REPORT A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SONG AND RESPONSES TO SONG PLAYBACK IN THE AVIAN GENUS PIPILO Peter S. Kaplan Department of Psychology University of Colorado at Denver Abstract An experiment was undertaken to characterize the responses of Green-tailed Towhees (Pipilo chlorura) and Rufous-sided Towhees (P. erythophthalmus) to each others' songs and to the songs of five other towhee species, plus one hybrid form. A total of 12 Green-Tailed Towhees and 10 Rufous-sided Towhees from Boulder and Gilpin counties were studied at three field sites: the Doudy Draw Trail, the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and on private land at the mouth of Coal Creek Canyon. In May, each bird was mist-netted and banded to facilitate individual identification. During the subsequent playback phase in June and July, each individual received one three-part playback trial on each of 7 consecutive or near-consecutive days. A 9-min playback trial consisted of a 3-min "pre-play" period, during which the bird was observed in the absence of song playback, a 3-min "play" period, in which tape recorded song was played to the subject from a central point in his territory, and a 3-min "post-play" period when the bird • was again observed in the absence of song playback. Order of presentation of song exemplars from different towhee species were randomized across birds. The main dependent measure was the change in the number of songs produced by the subject bird during song playback, relative to the pre-play period. Results showed that Green-tailed Towhees responded by significantly increasing their rate of singing, but only in response to Green-tailed Towhee songs. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

Life History Account for California Towhee

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group CALIFORNIA TOWHEE Melozone crissalis Family: EMBERIZIDAE Order: PASSERIFORMES Class: AVES B484 Written by: D. Dobkin, S. Granholm Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Program Staff, November 2014 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The former brown towhee recently has been split into the California towhee and the canyon towhee, M. fusca (American Ornithologists' Union 1989). The California towhee is a common, characteristic resident of foothills and lowlands in most of cismontane California. Frequents open chaparral and coastal scrub, as well as brush-land patches in open riparian, hardwood hardwood-conifer, cropland, and urban habitats. Commonly uses edges of dense chaparral and brushy edges of densely wooded habitats. Also occurs in lowest montane habitats of similar structure in southern California, and locally in Siskiyou and western Modoc cos. Local on coastal slope north of southern Humboldt Co., and apparently absent from western San Joaquin Valley (Grinnell and Miller 1944, McCaskie et al. 1979, Garrett and Dunn 1981). The Inyo California towhee, M. c. eremophilus, occurs only in the Argus Mountains of southwestern Inyo Co. SPECIFlC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds on seeds, insects, and some fruits. Gleans and scratches in litter, picks seeds and fruits from plants, and rarely flycatches (Davis 1957). Prefers to forage on open ground adjacent to brushy cover. Insects are important in breeding season, often constituting a third of the diet (Martin et al. 1961). Cover: Shrubs in broken chaparral, margins of dense chaparral, willow thickets, and brushy understory of open wooded habitats provide cover. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

California Rare & Endagered Birds

California brown pelican Pelecanus occidentalis californicus State Endangered 1971 Fully Protected Federal Endangered 1970 General Habitat: The California brown pelican uses a variety of natural and human-created sites, including offshore islands and rocks, sand spits, sand bars, jetties, and piers, for daytime loafing and nocturnal roosting. Preferred nesting sites provide protection from mammalian predators and sufficient elevation to prevent flooding of nests. The pelican builds a nest of sticks on the ground, typically on islands or offshore rocks. Their nesting range extends from West Anacapa Island and Santa Barbara Island in Channel Islands National Park to Islas Los Coronados, immediately south of and offshore from San Diego, and Isla San Martín in Baja California Norte, Mexico. Description: The brown pelican is one of two species of pelican in North America; the other is the white pelican. The California brown pelican is a large, grayish-brown bird with a long, pouched bill. The adult has a white head and dark body, but immature birds are dark with a white belly. The brown pelican weighs up to eight pounds and may have a wingspan of seven feet. Brown pelicans dive from flight to capture surface-schooling marine fishes. Status: The California brown pelican currently nests on West Anacapa Island and Santa Barbara Island in Channel Islands National Park. West Anacapa Island is the largest breeding population of California. In Mexico, the pelicans nest on Islas Los Coronados and Isla San Martín. Historically, the brown pelican colony on Islas Los Coronados was as large as, or larger than, that of recent years on Anacapa Island. -

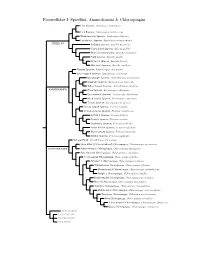

Passerellidae Species Tree

Passerellidae I: Spizellini, Ammodramini & Chlorospingini Lark Sparrow, Chondestes grammacus Lark Bunting, Calamospiza melanocorys Black-throated Sparrow, Amphispiza bilineata Five-striped Sparrow, Amphispiza quinquestriata SPIZELLINI Chipping Sparrow, Spizella passerina Clay-colored Sparrow, Spizella pallida Black-chinned Sparrow, Spizella atrogularis Field Sparrow, Spizella pusilla Brewer’s Sparrow, Spizella breweri Worthen’s Sparrow, Spizella wortheni Tumbes Sparrow, Rhynchospiza stolzmanni Stripe-capped Sparrow, Rhynchospiza strigiceps Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum Grassland Sparrow, Ammodramus humeralis Yellow-browed Sparrow, Ammodramus aurifrons AMMODRAMINI Olive Sparrow, Arremonops rufivirgatus Green-backed Sparrow, Arremonops chloronotus Black-striped Sparrow, Arremonops conirostris Tocuyo Sparrow, Arremonops tocuyensis Rufous-winged Sparrow, Peucaea carpalis Cinnamon-tailed Sparrow, Peucaea sumichrasti Botteri’s Sparrow, Peucaea botterii Cassin’s Sparrow, Peucaea cassinii Bachman’s Sparrow, Peucaea aestivalis Stripe-headed Sparrow, Peucaea ruficauda Black-chested Sparrow, Peucaea humeralis Bridled Sparrow, Peucaea mystacalis Tanager Finch, Oreothraupis arremonops Short-billed (Yellow-whiskered) Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus parvirostris CHLOROSPINGINI Yellow-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus flavigularis Ashy-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus canigularis Sooty-capped Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus pileatus Wetmore’s Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus wetmorei White-fronted Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus albifrons Brown-headed -

Conservation of Biodiversity in México: Ecoregions, Sites

https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/281359459_DRAFT_Conservation_of_biodiversity_in_Mexico_ecoregions_sites_a nd_conservation_targets_Synthesis_of_identification_and_priority_setting_exercises_092000_ -_BORRADOR_Conservacion_de_la_biodiversidad_en_ CONSERVATION OF BIODIVERSITY IN MÉXICO: ECOREGIONS, SITES AND CONSERVATION TARGETS SYNTHESIS OF IDENTIFICATION AND PRIORITY SETTING EXERCISES DRAFT Juan E. Bezaury Creel, Robert W. Waller, Leonardo Sotomayor, Xiaojun Li, Susan Anderson , Roger Sayre, Brian Houseal The Nature Conservancy Mexico Division and Conservation Science and Stewardship September 2000 With support from the United States Agency for Internacional Development (USAID) through the Parks in Peril Program and the Goldman Fund ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dra. Laura Arraiga Cabrera - CONABIO Mike Beck - The Nature Conservancy Mercedes Bezaury Díaz - George Mason High School Tim Boucher - The Nature Conservancy Eduardo Carrera - Ducks Unlimited de México A.C. Dr. Gonzalo Castro - The World Bank Dr. Gerardo Ceballos- Instituto de Ecología UNAM Jim Corven - Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences / WHSRN Patricia Díaz de Bezaury Dr. Exequiel Ezcurra - San Diego Museum of Natural History Dr. Arturo Gómez Pompa - University of California, Riverside Larry Gorenflo - The Nature Conservancy Biol. David Gutierrez Carbonell - Comisión Nal. de Áreas Naturales Protegidas Twig Johnson - World Wildlife Fund Joe Keenan - The Nature Conservancy Danny Kwan - The Nature Conservancy / Wings of the Americas Program Heidi Luquer - Association of State Wetland