California Towhee Responses to Chick Distress Calls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies

Wildlife of the North Hills: Birds, Animals, Butterflies Oakland, California 2005 About this Booklet The idea for this booklet grew out of a suggestion from Anne Seasons, President of the North Hills Phoenix Association, that I compile pictures of local birds in a form that could be made available to residents of the north hills. I expanded on that idea to include other local wildlife. For purposes of this booklet, the “North Hills” is defined as that area on the Berkeley/Oakland border bounded by Claremont Avenue on the north, Tunnel Road on the south, Grizzly Peak Blvd. on the east, and Domingo Avenue on the west. The species shown here are observed, heard or tracked with some regularity in this area. The lists are not a complete record of species found: more than 50 additional bird species have been observed here, smaller rodents were included without visual verification, and the compiler lacks the training to identify reptiles, bats or additional butterflies. We would like to include additional species: advice from local experts is welcome and will speed the process. A few of the species listed fall into the category of pests; but most - whether resident or visitor - are desirable additions to the neighborhood. We hope you will enjoy using this booklet to identify the wildlife you see around you. Kay Loughman November 2005 2 Contents Birds Turkey Vulture Bewick’s Wren Red-tailed Hawk Wrentit American Kestrel Ruby-crowned Kinglet California Quail American Robin Mourning Dove Hermit thrush Rock Pigeon Northern Mockingbird Band-tailed -

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of SONG and RESPONSES to SONG PLAYBACK University of Colorado at Denver

FINAL REPORT A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SONG AND RESPONSES TO SONG PLAYBACK IN THE AVIAN GENUS PIPILO Peter S. Kaplan Department of Psychology University of Colorado at Denver Abstract An experiment was undertaken to characterize the responses of Green-tailed Towhees (Pipilo chlorura) and Rufous-sided Towhees (P. erythophthalmus) to each others' songs and to the songs of five other towhee species, plus one hybrid form. A total of 12 Green-Tailed Towhees and 10 Rufous-sided Towhees from Boulder and Gilpin counties were studied at three field sites: the Doudy Draw Trail, the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and on private land at the mouth of Coal Creek Canyon. In May, each bird was mist-netted and banded to facilitate individual identification. During the subsequent playback phase in June and July, each individual received one three-part playback trial on each of 7 consecutive or near-consecutive days. A 9-min playback trial consisted of a 3-min "pre-play" period, during which the bird was observed in the absence of song playback, a 3-min "play" period, in which tape recorded song was played to the subject from a central point in his territory, and a 3-min "post-play" period when the bird • was again observed in the absence of song playback. Order of presentation of song exemplars from different towhee species were randomized across birds. The main dependent measure was the change in the number of songs produced by the subject bird during song playback, relative to the pre-play period. Results showed that Green-tailed Towhees responded by significantly increasing their rate of singing, but only in response to Green-tailed Towhee songs. -

Life History Account for California Towhee

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group CALIFORNIA TOWHEE Melozone crissalis Family: EMBERIZIDAE Order: PASSERIFORMES Class: AVES B484 Written by: D. Dobkin, S. Granholm Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: R. Duke Updated by: CWHR Program Staff, November 2014 DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The former brown towhee recently has been split into the California towhee and the canyon towhee, M. fusca (American Ornithologists' Union 1989). The California towhee is a common, characteristic resident of foothills and lowlands in most of cismontane California. Frequents open chaparral and coastal scrub, as well as brush-land patches in open riparian, hardwood hardwood-conifer, cropland, and urban habitats. Commonly uses edges of dense chaparral and brushy edges of densely wooded habitats. Also occurs in lowest montane habitats of similar structure in southern California, and locally in Siskiyou and western Modoc cos. Local on coastal slope north of southern Humboldt Co., and apparently absent from western San Joaquin Valley (Grinnell and Miller 1944, McCaskie et al. 1979, Garrett and Dunn 1981). The Inyo California towhee, M. c. eremophilus, occurs only in the Argus Mountains of southwestern Inyo Co. SPECIFlC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds on seeds, insects, and some fruits. Gleans and scratches in litter, picks seeds and fruits from plants, and rarely flycatches (Davis 1957). Prefers to forage on open ground adjacent to brushy cover. Insects are important in breeding season, often constituting a third of the diet (Martin et al. 1961). Cover: Shrubs in broken chaparral, margins of dense chaparral, willow thickets, and brushy understory of open wooded habitats provide cover. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

California Rare & Endagered Birds

California brown pelican Pelecanus occidentalis californicus State Endangered 1971 Fully Protected Federal Endangered 1970 General Habitat: The California brown pelican uses a variety of natural and human-created sites, including offshore islands and rocks, sand spits, sand bars, jetties, and piers, for daytime loafing and nocturnal roosting. Preferred nesting sites provide protection from mammalian predators and sufficient elevation to prevent flooding of nests. The pelican builds a nest of sticks on the ground, typically on islands or offshore rocks. Their nesting range extends from West Anacapa Island and Santa Barbara Island in Channel Islands National Park to Islas Los Coronados, immediately south of and offshore from San Diego, and Isla San Martín in Baja California Norte, Mexico. Description: The brown pelican is one of two species of pelican in North America; the other is the white pelican. The California brown pelican is a large, grayish-brown bird with a long, pouched bill. The adult has a white head and dark body, but immature birds are dark with a white belly. The brown pelican weighs up to eight pounds and may have a wingspan of seven feet. Brown pelicans dive from flight to capture surface-schooling marine fishes. Status: The California brown pelican currently nests on West Anacapa Island and Santa Barbara Island in Channel Islands National Park. West Anacapa Island is the largest breeding population of California. In Mexico, the pelicans nest on Islas Los Coronados and Isla San Martín. Historically, the brown pelican colony on Islas Los Coronados was as large as, or larger than, that of recent years on Anacapa Island. -

Voice in Communication and Relationships Among Brown Towhees

THE CONDOR VOLUME 66 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER, 1964 NUMBER 5 VOICE IN COMMUNICATION AND RELATIONSHIPS AMONG BROWN TOWHEES By JOET.MARSHALL,JR. This paper seeks to answer two questions: (1) What is the function of each song and call in brown towhees; that is, what information does a bird communicate to its fellows vocally, o’r how does it regulate their behavior by its voice? (2) What evi- dence does voice offer for understanding relationship by descent within the closely-knit group of brown towhee species? For the first, I would extend the analysis of Quain- tance (1938,194l) to all members of the group. As to the second question, an ingenious evolutionary reconstruction, based on museum and habitat studies, has been developed by Davis (1951). Do vocal attributes agree with his scheme? The three speciesof brown towhees, genus Pipdo, are the same size and general color and are more similar to each other than any one of them is to other ground-inhabiting finches in the same genus and in the genus Melozorte. Indeed, so close is their relation- ship that the same calls can easily be discerned in each species; although differing in timbre, similarity in form and usage proclaims them to be homologous. The Abert Towhee (Pipdo abed) occupies dense riparian woodland and mesquite thickets of the Colorado River and Gila River drainages, mostly in Arizona. The Brown Towhee proper (Pip20 fuscus) lives in brushy margins of openings in the southwestern United States and Mexico. The White-throated Towhee (Pipilo aZbicoZZis)inhabits brushy slopes, often with tree yuccas, in Puebla and Oaxaca, MCxico. -

Biology 2 Lab Packet for Practical 4 Birds

Bio 2 – Lab Practicum 4 1 Biology 2 Lab Packet For Practical 4 Birds Bio 2 – Lab Practicum 4 2 CLASSIFICATION: Domain: Eukarya Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata – Chordates Class: Aves – Birds Order: Struthioniformes - Ostriches Order: Galliformes - Quail Order: Rheiformes – Rheas Order: Gruiformes – Coots Order: Casuariiformes – Cassowaries Order: Charadriiformes – Gulls and Allies Order: Apterygiformes – Kiwis Order: Columbiformes – Pigeons Order: Sphenisciformes - Penguins Order: Psittaciformes – Parrots Order: Gaviiformes - Loons Order: Cuculiformes – Roadrunners Order: Podicipediformes – Grebes Order: Strigiformes - Owls Order: Procellariiformes – Tube noses Order: Caprimulgiformes – Nighthawks Order: Pelicaniformes – Pelicans Order: Apodiformes – Hummingbirds Order: Ciconiiformes – Herons/Egrets Order: Trogonifomes – Trogons Order: Phoenicopteriformes - Flamingos Order: Coraciformes – Kingfishers Order: Anseriformes – Ducks Order: Piciformes – Woodpeckers Order: Falconiformes – Raptors Order: Passeriformes - Songbirds Introduction – Birds Although chordates vary widely in appearance, they are distinguished as a phylum by the presence of four anatomical features that appear sometime during their life time. They exhibit deuterostome development and bilateral symmetry. Chordates only comprise 5% of the animal species but may be the most commonly known phylum. Birds are endothermic homeotherms which have adapted to many different ecosystems in the world. Station 1 – Class: Aves 1. What three adaptations do birds have for flight? 2. What do all species of birds have? 3. What dinosaurs did birds emerge within? When did they show up? 4. Where are birds found? Bio 2 – Lab Practicum 4 3 Station 2 – Evolutionary History - Archaeopteryx 1. What characteristics are seen in Archaeopteryx that are bird-like? 2. What characteristics are seen in Archaeopteryx that are reptile-like? Station 3 – General Characteristics - Feathers 1. What are feathers made of? 2. -

Passerellidae Species Tree

Passerellidae I: Spizellini, Ammodramini & Chlorospingini Lark Sparrow, Chondestes grammacus Lark Bunting, Calamospiza melanocorys Black-throated Sparrow, Amphispiza bilineata Five-striped Sparrow, Amphispiza quinquestriata SPIZELLINI Chipping Sparrow, Spizella passerina Clay-colored Sparrow, Spizella pallida Black-chinned Sparrow, Spizella atrogularis Field Sparrow, Spizella pusilla Brewer’s Sparrow, Spizella breweri Worthen’s Sparrow, Spizella wortheni Tumbes Sparrow, Rhynchospiza stolzmanni Stripe-capped Sparrow, Rhynchospiza strigiceps Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum Grassland Sparrow, Ammodramus humeralis Yellow-browed Sparrow, Ammodramus aurifrons AMMODRAMINI Olive Sparrow, Arremonops rufivirgatus Green-backed Sparrow, Arremonops chloronotus Black-striped Sparrow, Arremonops conirostris Tocuyo Sparrow, Arremonops tocuyensis Rufous-winged Sparrow, Peucaea carpalis Cinnamon-tailed Sparrow, Peucaea sumichrasti Botteri’s Sparrow, Peucaea botterii Cassin’s Sparrow, Peucaea cassinii Bachman’s Sparrow, Peucaea aestivalis Stripe-headed Sparrow, Peucaea ruficauda Black-chested Sparrow, Peucaea humeralis Bridled Sparrow, Peucaea mystacalis Tanager Finch, Oreothraupis arremonops Short-billed (Yellow-whiskered) Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus parvirostris CHLOROSPINGINI Yellow-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus flavigularis Ashy-throated Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus canigularis Sooty-capped Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus pileatus Wetmore’s Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus wetmorei White-fronted Chlorospingus, Chlorospingus albifrons Brown-headed -

Behavioural Processes Can a Solitary Avian

Behavioural Processes 82 (2009) 67–74 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Behavioural Processes journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/behavproc Can a solitary avian species use collective detection? An assay in semi-natural conditions Esteban Fernández-Juricic a,∗, Juan Antonio Delgado b, Carolina Remacha b, María Dolores Jiménez b, Vanessa Garcia c, Keiko Hori c a Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, 915 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA b Departamento de Ecología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, C/ José Antonio Novais, 2, 28040 Madrid, Spain c Department of Biological Sciences, California State University Long Beach, 1250 Bellflower Blvd. (Mailstop 3702), Long Beach, CA 90840-3702, USA article info abstract Article history: Collective detection (e.g., enhanced predator detection through the vigilance of conspecifics) is expected Received 15 January 2009 to have evolved particularly in social species. However, we assessed the degree to which an avian territorial Received in revised form 13 May 2009 species (California towhee Pipilo crissalis) would use social cues about predation in a semi-natural assay. Accepted 17 May 2009 We also exposed a social species (house finch Carpodacus mexicanus) to similar conditions. California towhees increased scanning rates when foraging with conspecifics, whereas house finches increased Keywords: scanning rates when foraging solitarily, suggesting that vigilance in these species is regulated mostly Anti-predator behavior through interference competition and through predation risk, respectively. California towhees did not Collective detection Early detection show early detection, and actually the last detector in the group delayed detection in relation to solitary Predator detection individuals. House finches benefited from early detection, but the second and last detectors maintained Territorial species detection at the level of solitary individuals. -

Avian Survey Report

Spring/Summer 2010 Avian Survey Report Stony Creek Wind Farm Wyoming County, New York January 24, 2011 PREPARED FOR: Stony Creek Energy LLC 51 Monroe St. Suite 1604 Rockville, MD 20850 PREPARED BY: Lackawanna Executive Park 239 Main Street, Suite 301 Dickson City, PA 18519 www.shoenerenvironmental.com Stony Creek Wind Farm Avian Survey January 24, 2011 Table of Contents I. Summary and Background .................................................................................................1 Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Project Description ........................................................................................................1 Project Review Background ..........................................................................................2 II. Bald Eagle Survey .............................................................................................................3 Bald Eagle Breeding Status in New York ......................................................................3 Daily Movements of Bald Eagle in New York ...............................................................4 Bald Eagle Conservation Status in New York ................................................................4 Bald Eagle Survey Method ............................................................................................5 Analysis of Bald Eagle Survey Data ..............................................................................6 -

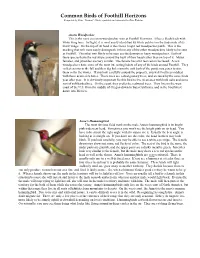

Common Birds of Foothill Horizons Compiled by Pam “Tenaya” Hardy, Updated and Amended by Dan Webster

Common Birds of Foothill Horizons Compiled by Pam “Tenaya” Hardy, updated and amended by Dan Webster Acorn Woodpecker This is the most common woodpecker seen at Foothill Horizons. It has a black back with white wing bars. In flight, it is most easily identified by white patches on the underside of its black wings. On the top of its head is the classic bright red woodpecker patch. This is the marking that will most easily distinguish it from any of the other woodpeckers likely to be seen at Foothill. The other two likely to be seen are the downey or hairy woodpeckers. Both of these species have the red stripe around the back of their head rather than on top of it. Males, females, and juveniles are very similar. The female has a bit less red on her head. Acorn woodpeckers have some of the most interesting habits of any of the birds around Foothill. They collect acorns in the fall and then dig holes into the soft bark of the ponderosa pines to store them in for the winter. If you look carefully around the property, you will find trees riddled with these acorn-size holes. These trees are called granary trees, and are used by the same birds year after year. It is obviously important for this bird to live in an area with both oaks and some sort of soft barked tree. On the coast, they prefer the redwood trees. They live on the west coast of the U.S. from the middle of Oregon down to Baja California, and in the Southwest down into Mexico. -

Vocal Behaviour of White-Eared Ground-Sparrows (Melozone Leucotis) During the Breeding Season: Repertoires, Diel Variation, Beha

Author's personal copy J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-015-1237-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Vocal behaviour of White-eared Ground-sparrows (Melozone leucotis) during the breeding season: repertoires, diel variation, behavioural contexts, and individual distinctiveness 1,2 2 1 Luis Sandoval • Carolina Me´ndez • Daniel J. Mennill Received: 7 March 2014 / Revised: 9 October 2014 / Accepted: 13 May 2015 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2015 Abstract There are relatively few quantitative descriptive variation in each category of vocalisation, and found that the studies of the vocalisations and vocal behaviour of tropical Ground-sparrows produced all three vocalisations at higher bird species, in spite of the tropic’s rich avian biodiversity output at dawn (between 0500 and 0600 hours) compared to and the extensive variety of vocalisations produced by the rest of the day. This study allowed us to conduct the first tropical birds. This lack of information inhibits our under- comparisons of vocalisations between White-eared Ground- standing of tropical animals, including our ability to perform sparrows and North American species in the genus Melo- comparative analyses on vocal behaviours from an evolu- zone, and revealed both similarities and differences between tionary perspective. In this study, we present the first quan- the species groups. Our investigation also showed that titative description of the vocal repertoire and daily vocal vocalisations related to communication within pairs and to activity of White-eared Ground-sparrows (Melozone leuco- territory defence (calls and duets) exhibited lower levels of tis), using focal and autonomous recordings collected during individual distinctiveness than vocalisations related mainly two consecutive breeding seasons in Costa Rica.